Sergio Ramírez, the illustrious historian, novelist, and former vice-president of Nicaragua, could well have been among his unfortunate friends and many other members of the opposition arrested by the regime of President Daniel Ortega and his weird wife and vice-president, Rosario Murillo, beginning in June. But in view of the fate of their friends and colleagues, Ramírez and his wife, Tulita, decided to leave Nicaragua. It was a wise move: in September Ramírez learned that he stands accused of money laundering and something called “provocation, proposition, and conspiracy.”

Ramírez is seventy-nine, and it is a cruel fate for someone who loves and has served his country as consistently as he has to know that he may never see it again, or his imprisoned friends, or his beloved writing desk and its surrounding walls of books. On the other hand, all experience is fodder to a writer, and Ramírez’s rich array of novels and historical essays—sixty years of ceaseless production—is a tribute to the tragic and absurd history of his beautiful homeland. Nicaraguans survive their lot with a trickster’s sense of humor, and Ramírez’s latest novel, Tongolele no sabía bailar (“Tongolele Had No Rhythm” might be the best translation of a title as clumsy as its protagonist), is a grim, wildly funny, surrealistic account of the grievous events of the spring of 2018, when student protests broke out in Managua and other cities around the country, and the repression served up by Ortega and Murillo left three hundred dead.

Ramírez tells the story through the character of Detective Dolores Morales, who was severely wounded in the fight to overthrow the dictator Anastasio Somoza back in the 1970s and wears a leg prosthesis as a result. The book’s other characters, however—all portrayed with swift dialogue and the author’s unerring ear for the sweet and extravagant Spanish of Nicaragua, with its sixteenth-century thees and thous and wild similes, and its joyful use of vulgarity whenever the occasion demands—are the most fascinating. They include Tongolele, a top intelligence officer working in the darkest corners of the government; a mild-mannered and heroic country priest; a startling woman who runs all the itinerant salesmen and -women in the country, with a sideline gathering intelligence for Tongolele; and a mystical spiritual adviser to someone referred to only as la compañera. That someone would be Vice-President Murillo, and though she is never seen or even named in the novel, Ramírez avails himself of the opportunity to trample merrily all over her shadow.

The novel’s account of the events of May 2018 is accurate, but it is when Ramírez’s narrative invention runs wildest that his portrayal of Nicaragua under the thumb of the improbable Ortega-Murillo duumvirate is most truthful. Because he was vice-president or the equivalent for the first ten years of the Sandinista regime, Ramírez has intimate knowledge of Ortega and his associates in the underworld of power, as well as of everyday Nica life. Non-Nicaraguans, though, might benefit from a decoder.

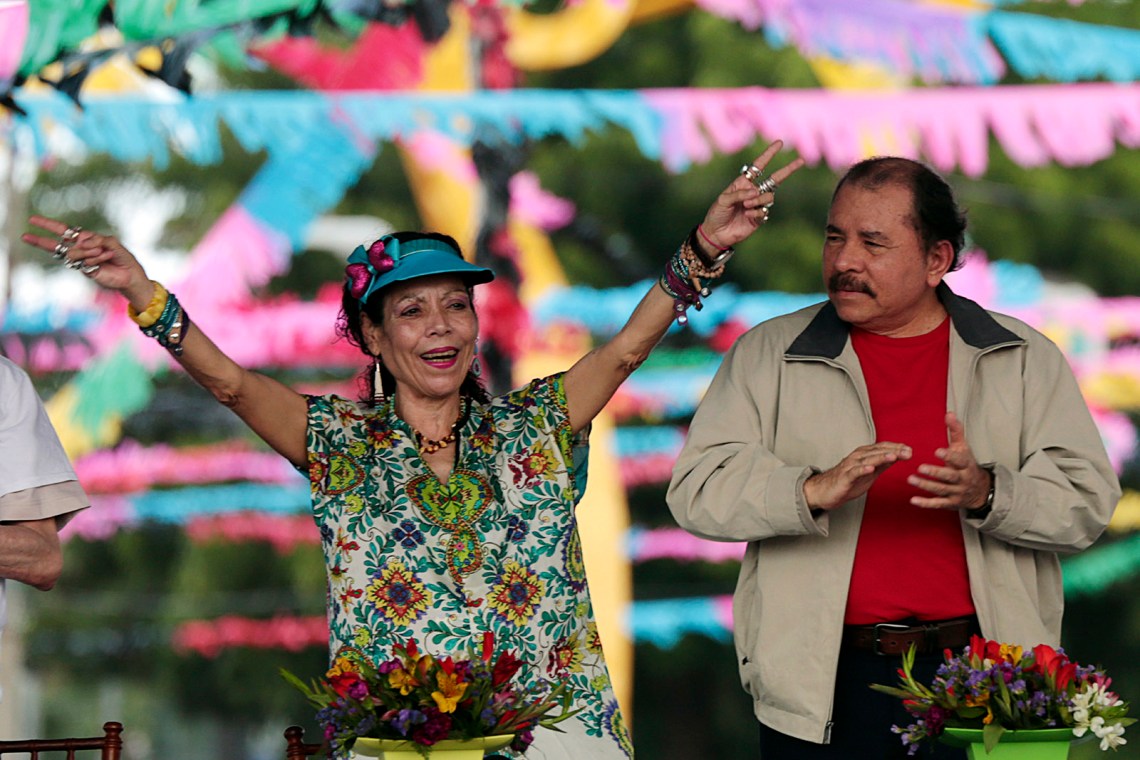

Ortega, seventy-six, loves to use the insult vendepatria—fatherland-seller—but he once agreed to sell the rights to a 278-kilometer-long strip of Nicaragua running from the Atlantic to the Pacific to a shadowy Chinese businessman who intended to build a canal parallel to and competitive with the one in Panama. Murillo, seventy, keeps meticulous track of every offense or snub she has ever suffered and communes with spirits who let her know who her hidden enemies are. Police and army battalions being insufficient to hold all the couple’s adversaries at bay, paramilitary groups are now deployed against peaceful demonstrators. Murillo had colorful curlicue metal silhouettes of trees installed all over Managua to channel positive energy from the skies. Strong evidence would indicate that Ortega is a pedophile and a rapist. Together, the doddering couple have created what Monsignor Silvio Báez, the auxiliary bishop of Managua (currently in exile) has called “a situation of…irrationality, violence and evil that surpasses the imagination.”

Who are these people? How did they get where they are? And why, after forty-two years of Sandinismo, are they still around?

You could say that Ortega’s real life began in prison. He was the son of an itinerant father, a barrio kid who together with his buddies joined the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN)—a tiny organization back then—as a fund-raising unit: the group held up stores and banks. He was first briefly jailed and tortured at the age of fifteen, then jailed in Guatemala and subjected to even greater abuse a year later, jailed again in Nicaragua and then freed under a general amnesty. In 1967, at the age of twenty-two, he was given a fourteen-year sentence for bank robbery that ended seven years early, when his guerrilla comrades rounded up a few hostages at a dinner party and exchanged them for him and thirteen other prisoners. The handful of poems Ortega published long ago mostly center on his prison life, and they are stark. “If you feed me you can fuck me/Three cigarettes gets you a blow job,” one begins. In another, he depicts the episodes of torture that prison authorities practiced on him almost recreationally: “Kick him/like that, like that, in the balls, the face/the ribs./Get the cattleprod, the bullwhip/talk/son of a whore/talk.”

Advertisement

In a perceptive and thorough biography, El Preso 198 (Prisoner 198), the journalist Fabián Medina Sánchez makes the case that Ortega has never really moved out of a prison cell.* He quotes a Playboy interview from 1987, in which Ortega describes how uncomfortable he was when he was released in 1974 and sent to Cuba, free to go wherever he pleased, and how, during a brief time back in Nicaragua in 1976, he discovered that he was actually much more relaxed in clandestinity, locked up in one room in a safe house, working in his underwear in the steaming Managua heat, meeting with the members of the Sandinista urban network and coordinating communication with guerrillas in the mountains. Medina tells us that after the Sandinista triumph in 1979 Ortega had a small room built in his new, expansive house, with a small window covered by a curtain and a hammock suspended in it, prison style, where he would spend much of his time. He ordered a similar, though windowless, room constructed for him in the bank building that initially served as the new government’s headquarters.

Ramírez, who as Ortega’s vice-president from 1985 to 1990 essentially administered the country, confirmed this in a conversation and added that whenever he stopped to pick Ortega up on the way to some early event, he was struck by the fact that Ortega would never sit down for breakfast but ate hurriedly while standing, and was never partial to anything other than the typical Nicaraguan rice and beans, tortillas, cheese, and black coffee. Better-quality ingredients than the gunk ladled out in prison, but a meal not unlike the one that would be on the prison menu.

Ortega has a younger brother, Humberto, who is articulate, ambitious, and very smart. Long ago, he mentioned to me in passing—I am paraphrasing, but not by a lot—that every family has a son who is audacious and destacado (stands out more), and another who is…not so much. Humberto has buckets more personality than his brother, which isn’t hard, considering that Daniel is as memorable as your average mop, and there is consensus among knowledgeable former Sandinistas I recently interviewed in Costa Rica that in 1978 the idea of bringing their scant guerrilla forces down from the mountains, where they had been circling for years, and into the cities, where they could spark a political movement against the dictator Somoza, was indeed Humberto’s, if you don’t count the constant backseat coaching by Fidel Castro.

Why, then, is Daniel president and not Humberto? Because, it is said, the struggle for power among Humberto and the other top two guerrilla leaders would have broken the FSLN, and it was reluctantly agreed to accept Humberto’s suggestion to put unthreatening Daniel in the highest position, first as a member of a transitional FSLN-civilian junta, in which Ramírez was the top civilian representative, and then as the triumphant Sandinista presidential candidate in 1984. But we are getting ahead of our story, because we have to describe Daniel’s momentous meeting with his future wife and vice-president, Rosario.

Much like Nicaragua’s history, which is to a striking degree the history of the same six or so last names, family traumas tend to run in loops. In addition to its account of the life and times of Ortega, Medina’s El Preso 198 provides an informative chapter on his wife. In 1967, he tells us, Murillo, a lively, rebellious sixteen-year-old, gave birth in Managua to a little girl. At the hospital her mother immediately took the baby away. A firm believer in spiritism, addicted to the Ouija board, she did not let Murillo nurse the child even once, convinced that her milk carried sinister humors. Instead, she turned the young woman out of the house, forcing her to marry the unwilling, clueless, and equally young father. The unhappy couple had one more child before the father died, allegedly of a drug overdose, in 1968.

Meanwhile, the grandmother had baptized the first baby with her own name: Zoilamérica. We can usefully compress some history here by explaining the name. It is pronounced identically to the words Soy la América (I am America)—America not in the sense of “United States” but in the sense of Latin America and the hemisphere—and it was a highly political name when it came into fashion a hundred years or so ago, expressing rejection of the US Marines who occupied Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933. It also implied admiration for Augusto César Sandino, who led a guerrilla war against the occupiers and was assassinated by the head of the National Guard, Anastasio Somoza García. Somoza went on to found a family dictatorship in 1937. The guerrillas who overthrew the last Anastasio Somoza in 1979 took the name of the hero Sandino for their movement. Sandino was an uncle of the matriarch Zoilamérica, and so the name was worn with extra pride.

Advertisement

Murillo grew into an adventurous adult. She married a second time; became involved in poetry groups; scandalized her mother by going to parties where marijuana was smoked; recovered her two children, Zoilamérica and Rafael Antonio, after her mother’s death; was hired as the secretary to the publisher and principal editor of the venerable opposition newspaper La Prensa; joined the underground support structure of the FSLN; got divorced; published a first, slender book of poems (Mexicans sing rancheras, Nicaraguans write poems); married a third time, to a midlevel Sandinista named Carlos Vicente Ibarra; and, while pregnant, fled the country with her new husband at a particularly brutal moment of Somocista repression. Their first stop was Caracas, both of them convinced that they were done with politics and wanted only to study filmmaking in Paris and make movies. Murillo was wandering among the various exhibits and portraits in the house where the hero of Latin American independence, Simón Bolívar, was born, when she bumped into a fellow Nicaraguan with whom she had corresponded while he was in prison, a stolid man in thick square-framed glasses: Daniel Ortega. According to Murillo, she was instantly struck by “his skinniness, his magnetism that was for me electrifying.”

For his part, Ortega later said that, as a man of few words, “I’m more about action. There is a communication that is stronger and more profound that is with the eyes.” Shortly after locking eyes with Murillo and, presumably, renewing her commitment to Sandinismo, Ortega was appointed the FSLN spokesman abroad, based in Costa Rica. Not long after that, the heavily pregnant Murillo arrived in San José with her husband and children. Ibarra was quickly sent to Cuba to study film, and Ortega and Murillo moved in together, hungry exiles of scarce means and great revolutionary fervor who lived almost in hiding even abroad.

Dramatic events marked the couple’s tumultuous life. Murillo’s former boss at La Prensa, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, whose ancestors included four presidents of Nicaragua, had participated in armed expeditions against the first Somoza and served time in the second Somoza’s monstrous prisons. A highly visible figure, he was assassinated on the third Somoza’s orders in January 1978, which sparked a brief, unprecedented popular rebellion.

In August of that year a second rebellion began, in which the remarkable Dora María Téllez, then twenty-two, was Comandante Dos, or Commander Two. Led by Edén Pastora, Commander Zero, twenty-five guerrillas dressed in army uniforms drove two trucks up to a building popularly known as the Pigsty but more formally as the National Palace, where both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies were housed. “[Our] truck was supposed to be olive green but we couldn’t find the right paint, so we painted it parrot green instead,” Téllez recalled when I interviewed her a year later. By the time the security forces realized they had not been paying enough attention to the nuances of green, the guerrillas controlled all the strategic posts in the building and had taken some two thousand people hostage.

There was something about Pastora’s dashing air, Téllez’s youth, and the nose-thumbing chutzpah of the takeover that instantly brought the Sandinistas worldwide attention and earned them a passionate international following. The guerrillas kept a couple dozen hostages to bargain with and designated Téllez—currently being held in one of Ortega’s prisons—their chief negotiator: two days later Somoza agreed to the ransom amount and released fifty-nine Sandinista prisoners. Guerrillas, freed prisoners, and a handful of hostages traveled in a sunny yellow school bus to the airport, where they boarded a plane to Cuba. But along the way both Somoza and his challengers got a big surprise: the road was lined with thousands of cheering Managuans, most of them visibly poor, all of them experiencing a brand-new kind of laughter: los muchachos—the kids—had played such a great trick on that old Somoza bastard! Sandinista recruitment climbed to near-unmanageable levels in the following months as the insurrection spread throughout Nicaragua.

In July 1979 Somoza fled the country. The Sandinista leadership converged in Managua, shocked at the speed of their triumph. They were, for the most part, terribly young, barely educated—like Ortega, many of them had cut their studies short in order to take up arms against Somoza—and dependent on Castro for counsel on every issue. They failed to realize a crucial law of politics: You can voluntarily cede power, but there’s no asking for it back. And so Daniel Ortega was appointed to a civilian-Sandinista transitional junta and set on his way to becoming the most powerful man in the land. With Murillo and her three children, whom he eventually adopted, he moved into a luxurious house confiscated from one of the wealthiest men in Nicaragua. Throughout Managua there was a hunt by guerrillas looking for houses to confiscate and move into, the fancier the better. Where else, they may well have thought, were winners supposed to live? Conceivably not in the fleeing oligarchy’s houses.

It’s hard to know if by the time she set up housekeeping in her new domain, Murillo was already aware that her husband had made a habit of sneaking into the room where her oldest daughter, Zoilamérica, then eleven, was sleeping. It took years of abuse—variously condoned or ignored by her mother, she told me in an interview—before she felt strong enough to denounce her abuser in public. At last, on March 2, 1998, Zoilamérica, a tall, slender, visibly nervous thirty-year-old with a degree in sociology, sat down in front of a crowd of reporters and announced that the president of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega, her stepfather, was a rapist:

From the age of eleven I was sexually abused…[by the president] repeatedly and for many years…. Recovering from the effects of this long aggression, with the accompanying sexual assault, threats, harassment, blackmail, has not been easy.

In a painfully detailed forty-page court deposition, given ten weeks after the press conference, Zoilamérica related, among other things, that in Costa Rica, when she was small, Ortega would creep into the room she shared with her little brother and grope her while she lay frozen, pretending in shame and horror to be asleep. Later, in Managua, Ortega’s sexual predation continued in the privacy made possible by their new house’s many rooms. Zoilamérica was given her own room, where he could fondle her in relative privacy. She was forced to spend many hours in the windowless room in his office. He spied on her through the keyhole when she was in the bathroom, then took to walking straight in. Eventually, she wrote, Ortega “no longer simply watched me as I bathed; he would…masturbate. It was horrible at that age to see a man leaning against a wall for balance and shaking his sex as if lost, unconscious even of himself.”

In time, Zoilamérica reached puberty. Ortega walked into her room one night, examined her, said, Ya estás lista (You’re ready), and raped her.

In the first of Sergio Ramírez’s Detective Morales novels, there is a hidden detail. It’s tiny, but Nicaraguan readers knew why it was there: Morales spots a truck driven by an older man who is enthusiastically telling a story to a little girl in the passenger seat. She listens with her eyes fixed solemnly on the road. A grandfather and his grandchild, Morales thinks in a rare sentimental moment. Then he sees the truck drive into a sex motel. The second Morales novel hinges on the story of a young woman who since childhood has been raped by her stepfather, a powerful businessman.

Zoilamérica’s case against Ortega went nowhere: one of the many judges with whom he had filled the judicial system ruled that the statute of limitations on his alleged crimes had run out. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ended up recommending that the dispute be resolved between the parties involved. Public reaction would have been different if Murillo had come out in defense of her daughter, but instead, Zoilamérica says, her mother had fits of jealousy, accused her of seducing her stepfather, ran her out of the house just as her own mother had thrown her out, and then, when the scandal finally broke, stood weeping and sniffling beside Ortega while he told a crowd, “Rosario said to me that she wants to apologize to the pueblo for having given birth to a daughter who betrayed the principles of Sandinismo.”

Afterward the couple’s physical transformation began. Murillo used to dress normally but with a certain snap, an occasional extravagance. Today we have the Murillo of the crazy makeup, the pink or turquoise Indian-style dress, and the dozens of good-vibration-channeling rings, bracelets, necklaces, and earrings she arms herself with every day. She consults the spirit of Augusto César Sandino’s brother on a regular basis (why, one wonders, is she not allowed to commune with the great hero himself?) and paces about lighting incense sticks in a house filled with plaster cherubim and images of the Buddha. In her fluty voice she swerves from preaching peace and love, as the spirit of Sai Baba, her Indian spiritual master, demands, to denouncing

those diminished brains that work…receiving messages…from other galaxies, really, from other planets, that supposedly come to elevate their fatherland-lacking condition…. The abject condition of people who do not know love for the fatherland and are waiting for the spaceships to activate their diminished brains.

The scandal of Ortega’s systematic rape of his stepdaughter subsided, but its poison continues to seep through Nicaragua’s history, because it forced Sandinistas at every level to believe yet more lies from their leaders: they did not engage in small or large acts of corruption; they were really democrats at heart, or they were really socialists at heart; the majority of the population really loved them; and of course Zoilamérica was lying. (Even though, as a canny Nicaraguan journalist observed, in the anything-goes promiscuity that followed the Sandinistas’ victory, it was generally assumed among his inner circle that Ortega’s good-looking stepdaughter, all grown up, was in fact his mistress: “What shocked everyone was her revelation that he was also a pedophile.”)

Throughout the long years of Zoilamérica’s abuse (she was divorced with two children by the time she went public with her accusation, in an attempt to stop Ortega’s unremitting pursuit), Nicaraguan politics unfolded in their circular way. In 1990 Ortega was defeated at the polls by the fifth Chamorro to become president: Violeta Chamorro, a straight-backed, pious homemaker and widow of the assassinated editor Pedro Joaquín Chamorro. Jimmy Carter, among others, persuaded Ortega and the Sandinista party leadership to recognize Doña Violeta’s victory. Five years later Sergio Ramírez, Ortega’s former vice-president, resigned from the party and founded an opposition movement with other dissident Sandinistas, while Ortega spent the next seventeen years attempting to get the presidency back.

Fabián Medina reminds us that Ortega succeeded thanks to some skillful constitutional meddling that allowed candidates to win with as little as 35 percent of the vote. With further wrangling, Ortega returned to power in 2007 with 38.07 percent of the vote and has been president ever since. His corrupt and dictatorial brand of Sandinismo has destroyed the movement’s proudest achievements. The stubborn journalist Carlos Fernando Chamorro—a former Sandinista, son of Doña Violeta and Pedro Joaquín, and founder and editor of the invaluable online magazine Confidencial—put it succinctly:

Ortega reestablished electoral fraud as a practice, outlawed and repressed the opposition, and established a monopoly over the estates—the Supreme Court, the electoral authority, and the Office of the Comptroller—transferring the one-time jewels of the democratic transition, the Armed Forces and the Police, to the political control…of the presidential couple.

There is no way of knowing whether Carlos Fernando Chamorro’s older sister Cristiana, one of Ortega’s potential opponents, would have been elected president on November 7 if she had not been under house arrest since June. But the ruling couple, with a network of spying “people’s associations” and top-notch private pollsters at their command, must have thought in panic that Chamorro’s victory was indeed likely, or they would not have risked the international opprobrium and renewed sanctions that inevitably followed the move against her—the might-have-been sixth Chamorro family president of Nicaragua—and the equally outrageous imprisonment of six other candidates who might have run against Ortega and honorary co-president Rosario Murillo. (Ortega promoted her from her previous position as vice-president just before the election.)

However that may be, elections in Nicaragua came and went, and nothing happened that was not foreseen: Ortega and Murillo remain in power despite an estimated 40 to 80 percent abstention rate, depending on who’s counting. With the help of judges who do the couple’s bidding, their victory was certified as fair, even though the seven arrested would-be candidates have not been freed, nor have the dozens of other activists, opposition leaders, lawyers, journalists, and ordinary citizens rounded up since June. Most of the prisoners are elderly, and several are being held under appalling conditions of hunger and psychological torture.

But the so-called elections are an unimportant chapter in this dispiriting telenovela. What matters is what happens next. Can renewed or stiffer international sanctions accomplish anything more than increasing the privations of the impoverished citizenry? Has the terrible Ortega-Murillo assassination spree against students and campesino leaders in 2018 permanently terrified the population into despair or indifference? Will the plump and satisfied business sector—so recently the regime’s greatest ally—rebel now that police have jailed two of its most important representatives? Nicaraguans at home and in exile are anxiously waiting to find out. Perhaps nothing will happen. Perhaps, in history’s unpredictable way of jostling itself awake and taking off at a canter, some enormous change will come to ease the suffering of that troubled land.

—November 18, 2021

This Issue

December 16, 2021

Labors of Love

Exhilarating Antihumanism

-

*

Madrid: Alfaguara, 2018; reviewed by Stephen Kinzer in these pages, September 23, 2021. ↩