On April 29, 1934, Robert Frost wrote to his friend Louis Untermeyer that his “favorite poem long before I knew what it was going to mean to us was [Matthew] Arnold’s ‘Cadmus and Harmonia.’” In the original myth, Cadmus, founder of Thebes, and his wife, Harmonia, endure the deaths of their five children as retribution for Cadmus’s killing a serpent prized by the god Ares. Arnold’s version picks up late in the couple’s story, after the “grey old man and woman” have begged to be transformed into “placid and dumb” snakes, “far from here” among the grasses and mountain flowers of Illyria. There, “The pair/Wholly forgot their old sad life, and home,” writes Arnold. No longer reliving “the billow of calamity” that “Over their own dear children roll’d,/Curse upon curse, pang upon pang,” Cadmus and Harmonia are at last “placed safely in changed forms.”

A few days later, Frost again wrote to Untermeyer, reporting that his youngest daughter and favorite child, Marjorie, had died of a postpartum infection. “Here we are Cadmus and Harmonia not yet placed safely in changed forms.” But the letter describing Marjorie’s final days, one of the most powerful Frost ever wrote, is itself a change of form from the raw distress that it describes:

Marge always said she would rather die in a gutter than in a hospital. But it was in a hospital she was caught to die after more than a hundred serum injections and blood transfusions. We were torn afresh every day between the temptations of letting her go untortured or cruelly trying to save her. The only consolation we have is the memory of her greatness through all. Never out of delirium for the last four weeks, her responses were of course incorrect. She got little or nothing of what we said to her. The only way I could reach her was by putting my hand backward and forward between us, as in counting out and saying with overemphasis You—and—Me. The last time I did that, the day before she died, she smiled faintly and answered All the same, frowned slightly and made it Always the same.

Though it feels cruel to notice it, you can find in this tragic last scene between father and daughter the primal elements of a Frost poem: that “counting out” and meaning-making by selection and “overemphasis” is his prosody in action. He dreamed of sentences stripped of their words, pared down to their “sentence sounds,” those “brute tones of our human throat that may once have been all our meaning.” Here the entirety of English has been painfully reduced down to six words, Frost’s three and Marjorie’s three. The “brute tones” and the accompanying pantomime alone communicate the meaning. Once extraneous language enters the picture, confusion and frustration—Marjorie’s smile turning into a frown—soon follow.

Frost’s “not yet” (“Here we are Cadmus and Harmonia not yet placed safely in changed forms”) was wishful. He and his wife, Elinor, had good reason to hope that the prophecy of Arnold’s poem had finally revealed its entire “meaning”: Marjorie was the third of their six children to die. A son, Elliott, was lost in 1900 at the age of four, after a homeopathic remedy for cholera failed. A baby daughter died three days after her birth in 1907. But “Cadmus and Harmonia” bore further, still unimagined, implications. In 1938, four years after Marjorie’s death, after years of marital discord, Elinor died of heart disease, refusing to call Frost to her deathbed. Their son Carol, troubled by mental illness since childhood, slid into despair and killed himself with his hunting rifle in 1940. His body was discovered in the kitchen of their stone farmhouse by his fifteen-year-old son, Prescott. Frost found reasons to blame himself for every one of these tragedies. His two living children, Irma and Lesley, sought a protective distance from the maelstrom that had swept most of their family away.

And so by 1940, at the age of sixty-six, Frost, perhaps the most famous and beloved American poet, had suffered a series of losses almost unimaginable to the fortunate among us. By one way of counting, he was more or less alone in the world.

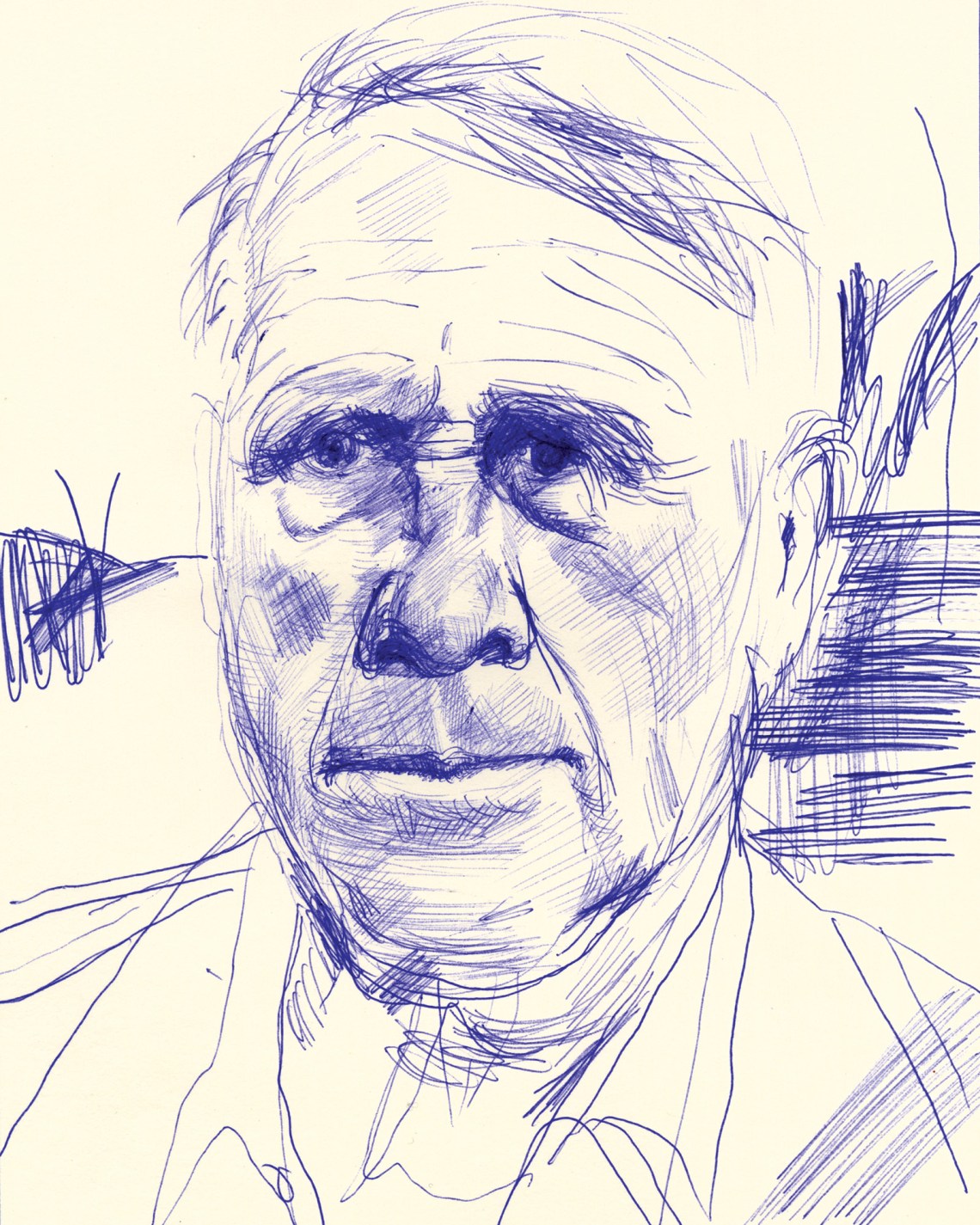

This period that broke Frost also led to his seeking audiences (and, more and more, poems that pandered to them) as a distraction. Stories abound from his later years of the poet’s wearing his students and friends out by performing long into the night. Rarer, though, were the intimate confidences imparted to Robert Lowell, his young “friend in the art”—the art of writing, but also of bearing misery, and perhaps the specific misery of bipolar disorder. In a sonnet published in 1969, Lowell memorably captured the elderly Frost as he combed through the debris of his personal life:

Advertisement

Robert Frost at midnight, the audience gone

to vapor, the great act laid on the shelf in mothballs,

his voice musical, raw and raw—he writes in the flyleaf:

“Robert Lowell from Robert Frost, his friend in the art.”

“Sometimes I feel too full of myself,” I say.

And he, misunderstanding, “When I am low,

I stray away. My son wasn’t your kind. The night

we told him Merrill Moore would come to treat him,

he said, ‘I’ll kill him first.’ One of my daughters thought things,

knew every male she met was out to make her;

the way she dresses, she couldn’t make a whorehouse.”

And I, “Sometimes I’m so happy I can’t stand myself.”

And he, “When I am too full of joy, I think

how little good my health did anyone near me.”

The set list Frost liked to read for audiences in his old age excluded some of his best, and almost all of his most revealing, poems—“Home Burial,” “The Subverted Flower,” “A Servant to Servants.” These poems were in essence suppressed. The process of retrieving Frost from the spectacle of his own self-erasure—Randall Jarrell called him “the Only Genuine Robert Frost in Captivity”—began soon after his death.

With every volume of his letters that appears, Frost grows more vivid, even as “the great act” fades from memory. The poet we meet at the beginning of The Letters of Robert Frost, Volume 3: 1929–1936, edited by Mark Richardson, Donald Sheehy, Robert Bernard Hass, and Henry Atmore, is nearly fifty-five, at the height of his artistic powers and on the cusp of literary celebrity. He is in the midst of a period of bold, if frantic, accumulation—of status, along with property. In 1928 Frost purchased a second farm, which he named the Gully, in the Vermont town of South Shaftsbury, a mile or so from the stone house that he had given as a present to Carol and his family in 1924. Frost looked forward to the publication of his Collected Poems by Henry Holt in 1930; as part of the deal, he was made a shareholder in the firm.

In 1926 Frost had again taken up teaching at Amherst College, on enviable terms—terms that were, indeed, noted with considerable envy by his colleagues. Though his duties were light, soon he bought a house in Amherst, a fine stick-style Victorian, built for the president of the Massachusetts Agricultural College, with distant mountain views. The Frosts also owned a summer house in Franconia, New Hampshire, high in the mountains above the ragweed line (Frost suffered terribly from hay fever). Owning four houses means that you’re not at home even when at home—which, in any case, Frost often wasn’t: a busy countrywide touring schedule, made necessary, in part, by all those expenses, put him in front of rapturous audiences from coast to coast. “If you see me start a real estate agency pretend not to notice,” he wrote to a friend, Lew Sarett. “Oh yes I have some of the arts of the salesman.”

We know from the pedagogy laid out in Frost’s poems how to understand, at metaphysical scale, the contradictory drives—toward building, toward tearing down—that troubled him during this period, but the letters often tally human costs unexplored in those well-known formulations. In “The Wood-Pile,” Frost comes across a “cord of maple, cut and split/And piled—and measured, four by four by eight,” abandoned in a snowfield, “far from a useful fireplace.” Its meticulous making and measuring is just the sort of work a poet does with language against the white field of the page. Also like a poet, whoever built this thing forgot all about it once he’d finished, consumed by “fresh tasks”:

I thought that only

Someone who lived in turning to fresh tasks

Could so forget his handiwork on which

He spent himself, the labor of his ax….

This is of course a sanitized moral scenario. The woodpile feels nothing at all when it is forgotten. Its abandonment by the woodchopper, in fact, allows this little man-made artifact to rejoin nature, where it might “warm the frozen swamp as best it could/With the slow smokeless burning of decay.” Frost’s metaphors for poetry-writing often stage it this way, as a morally neutral and self-expending process: poems are “bits of order” fringed by chaos, or “a momentary stay against confusion,” or “cigarette smoke rings” dispersing even as they form. They exhaust their author’s ingenuity; then they end.

But the “bits of order” Frost constructed in his life were not so easily put aside. The world of obligation seems to be gaining on him from the opening pages of this volume. Around March 14, 1929, Frost wrote to a young protégé, the woodsman-poet Wade Van Dore, “I wonder what you would say to taking charge of my farm for a year.” Then, Frost provided this baffling prospectus:

Advertisement

The work could be as much or as little as you cared to make it. There would be tree-planting and tree-moving. There would be tearing down some of the old buildings we want to get rid of. There would be some trench digging and stream damming. There would be some repairing and doing over of the old house (a real antique but in only a so-so state of preservation) and there would be some improving of the road in to attend to. There would be or could be; as I say you could decide for yourself how much of anything you cared to give time to.

Frost seems less interested in the maintenance of the farm than in performing for a fan—mixing tones, playing with the senses of “would be” and “could be,” and taking characteristic pleasure in the piled-up gerunds. And he’s put his hired man in some Frostian predicaments: how to cultivate the conditional as a permanent state of mind; how to put down stakes in the participial flux of nature; how to make choices within an environment that does not yield to human agency. Frost’s last ambiguous mandate, the most important of all, picks up the syntax of those prior non- or un-assignments: “You could take all the time you pleased for your writing.”

But writing solves only the problems of writing; it can’t keep the road cleared or the furnace lit. Van Dore’s stay at the farm seemed predestined to fail—or, to put it another way, to succeed in failing, and therefore to bear out some of Frost’s favorite, darkly scenic hypotheses. “My farm is fast going back to wilderness—as fast as can be expected,” he told Untermeyer in August 1929. Frost’s poems often study human responses to the encroaching wilderness, but in the “wilderness” of Frost’s farm Van Dore soon confronted a variety of human trouble. Carol, a brooding, unsettling presence, might “be with you a little,” the poet wrote to Van Dore: “I hope you will like him for all his reserve and timidity. You won’t find him bookish, but you will find him fond of the land.”

Frost had also invited (apparently without informing Van Dore) an impoverished friend, the illustrator J.J. Lankes, to camp out with his wife and four children on his land, while Van Dore enjoyed the relative comforts of a roof over his head. “Lankes is over at the Gully camping out,” Frost wrote to Untermeyer, pitting the two men against each other. “But I am afraid we are not giving him just the company he wants in Wade Van Dore.” Lankes “has a family of four to work for and Wade’s emancipation rouses his wrath and jealousy.” Wade, for his part, had already proven to be “a strange boy. His mother tells us that his obediently doing what he is asked to do throws him into long cataleptic sleeps afterward.”

At times, Frost appears to be entertained by the rivalries he has put into motion back on his farm, but the word “wrath” suggests the specter of violence, madness, and fear to be found throughout these letters, elements natural to the hardscrabble pastoral Frost explores in his work—in poems like “A Servant to Servants” (for me, maybe the most frightening poem in English) and the ferocious anti-Eden of “The Subverted Flower.” In September 1929 Frost abruptly changed his tone with Van Dore: “You speak of the hope of so conducting your future life as to please me. You can please me only by pleasing yourself. I have little use for any who haven’t seen a way of their own to live.” Slapped back a little, Van Dore is then invited back in, but with a condition: “In here and there a detail you might show your friendship for me by deferring to my wishes—as in the matter of Walter Hendricks.” Hendricks, a founder of Marlboro College in Vermont, would later reenter Frost’s graces, but in 1929 Frost considered him to be a kind of stalker:

You can’t tell him not to come now that you have invited him. I don’t want him affronted or hurt. I dont want a case or an issue made of his visit. But please for my sake say nothing to Carol of his visit and don’t take him near the other houses.

The “other houses” included one where Frost’s daughter Irma lived with her son and husband. A note in this edition explains the root of the conflict: Irma had confided to her father that Hendricks, who was Frost’s student at Amherst, had made sexual advances upon her while she was a teenager in his care. According to the note, Irma “suffered from paranoid fantasies, often of sexual predation, and RF concluded that Hendricks had been wrongly accused.” It is impossible to know what happened; certainly there was never another inkling of such behavior from Hendricks. But in 1929 Frost still very much feared the young man’s “persistence in keeping on my trail,” and warned Van Dore to stay away from him: “You surely cant mean to make me real trouble.”

If the Gully was a site for the rivalries among Frost’s protégés to play out, it was the stone cottage a mile or so away where Frost’s “real trouble” lay. Carol had, in a way, laid claim to the cottage even before Frost could give it to him. Two years earlier, in 1922, after an argument about a plan to spend thirty-five dollars on a rooster, Carol, then nineteen, walked out the front door of the Frosts’ house in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and set out on foot for South Shaftsbury, vanishing for days. He turned up at the stone cottage, where, according to Frost, he was “having a fine time building a hen house.”

The portrait of Carol in the third volume of Lawrence Thompson and R.H. Winnick’s biography of Frost leans too heavily on his father’s own account of his son’s misery. The chapter is melodramatically titled “The Death of the Dark Child.” Thompson and Winnick cannot, as Frost and his family could or would not, address Carol’s mental illness and need for psychiatric care. (If Lowell’s sonnet is to be trusted, Frost saw his son as capable of committing murder.) Instead the biographers pass down Frost’s own folk diagnosis of his son’s troubles. In June 1911 the Frosts’ landlord in Derry, New Hampshire, committed suicide. “Frost tried to comfort and reassure his children that Russell’s life had been a happy one, that it had reached a kind of fulfillment,” Thompson and Winnick write.

But the children, in their play with neighborhood friends, soon heard the word “suicide,” and gradually they picked up the details of how Lester Russell had killed himself. For nine-year-old Carol, there seemed to be a curious problem in trying to correlate his father’s word “fulfillment” and the other word, “suicide.” Thereafter, at various points and crises in his life, he often spoke of committing suicide when it seemed to him that he, too, had reached “fulfillment.”

Frost’s answer was to keep Carol supplied with tasks, land to manage, animals to care for, out of fear he would decide he was “fulfilled.”

Sometime in the early 1930s, though, Carol Frost began suggesting to his family that, according to Mark Richardson, he “hoped to publish a volume of poetry.” In a letter from January 1932, Elinor Frost alerted Lesley, Carol’s sister, to the potential trouble ahead. “It isn’t that papa doesn’t think there is some good in what Caroll [sic] has done,” Elinor wrote, but that “Caroll isn’t willing to be told things, & also that he fears Caroll’s ambition will get away with him.”

Writing poetry seemed not only a dangerous investment of Carol’s hopes but, increasingly in these letters, an ambition he’d picked in order to provoke his father’s discouragement. In short, Frost and his son are on a collision course throughout this volume, with the issue of Carol’s writing poetry a dangerous accelerant. Frost does all he can to somehow steer out of this awful trajectory, often with patience, sometimes with pique. Carol was not “bookish,” as Frost told Van Dore. His being “fond of the land” was the official party line, the strategy, the therapy. Carol has “put in a cement reservoir and laid iron pipes,” Frost boasts. He “is off this minute buying three or four pedigreed sheep.”

Careful readers of Frost have long noted that his dramas of human agency are set against a huge, cosmic backdrop, where a choice such as which path to take at a fork in the woods is ultimately meaningless. “The Road Not Taken” has taken many earnest students down a road toward concluding that their own belief in nonconformity and personal courage is shared by Frost. Their teachers then disabuse them of those quaint misperceptions. This is also the pedagogical cat-and-mouse game that plays out in many of Frost’s letters to aspiring poets, but never to his son. Van Dore’s poetry had won Frost’s admiration, though his presentation of his first book, Far Lake, dedicated to his mentor, caused Frost to draw back: “Dont do a thing for me you dont want to do. I can reconcile myself to watching you dream your life away.” Frost could not so easily reconcile himself to Carol’s dreaming his life away, since he knew the kinds of dreams that taunted him.

“Frost is almost never at a loss as to how to ‘carry himself’ in letters, except when writing to Carol, to whom his manner of address is seldom sure,” writes Richardson, in the brilliant introduction to this volume. There is precision in Frost’s writing advice to Carol, and often cautious support, but on the whole the letters radiate dread. The word that keeps cropping up, on both sides of the correspondence, is “mistake.” “Quite often I can control my speed on the typewriter to do perfect work, but not today,” Carol wrote, in 1932.

There has just been a bunch of boys playing on a piece or [sic] the larger section of the lawn I have spent all week spading and getting mellow for new seed, which has me riled up so I can’t keep my mind on the work. That seems to be the big difficulty, as one learns ones [sic] speed increases thereby making just as many mistakes, control of ones nerves is the main factor.

Carol’s fear of making mistakes in his writing rises above subtext in these letters. It becomes their subject, their fixation; and even as he deplores his own mistakes, he makes new mistakes: “I wrote this letter in some what of a hurry on the spur of the moment to take down and mail today. There are a few more mistakes than usual.”

As his son’s letters about his mistakes pile up with mistakes, Frost’s letters back become more explicitly aimed at calming his nerves. In 1931 Frost wrote to Carol, then living with his family in California, of a couple who had rented the stone house in his absence and wanted to grow sweet peas:

Before I forget it: a nice thing you could do for the Shaws would be to write them out very carefully and clearly all you know and think they should know about raising cultivating handling and selling sweet peas…. Make it simple and easy to follow. Emphasize the important things. Tell them about the rotation you planned and about the brush string and wire supports. I tried to tell them a little but I didnt know enough. Introduce the subject by mentioning me and telling them I told you of their interest.

This is a connect-the-dots: Frost’s fear that having to write a simple note will cause his son extraordinary distress comes through, as it must have come through for Carol, too. The advice is not even really about writing but about the sequencing of thought (“write them out very carefully and clearly”) and the calm presentation of Carol’s mind. As always, Frost denigrates his own knack for one sort of work—the planting of peas—in order to even out his advantage in another sort of work, writing. It seems clear that he did not rank one above the other, but admired prowess in either equally. Writing was as much a metaphor for physical labor as physical labor was for writing. To judge from Frost’s own anxieties about farming, he valued Carol’s skill with sweet peas as much as he admired the merely competent verse, often imitative of his own poems, that was written and sent to him by many a young admirer.

Often, therefore, Frost accentuates his own mistakes. “It cuts down the size of the United States to have someone in our own family cross it in a small car on the highway in ten or twelve days the way you do,” he wrote to Carol on September 9, 1933. Driving his own new car while sick with the flu, Frost could barely manage the mountain roads near Franconia: “I had in mind what you said about the art of holding a perfectly even rate and made that my interest and object.” Again and again Frost tried to assume the role of apprentice to his son’s gnosis. When Frost’s beloved Newfoundland, Winnie, was attacked by porcupines, Frost killed the dog while trying to save it. “You manage to cross the whole continent without making any mistake,” he wrote to Carol on September 18, 1933.

And I can’t stay in one place three weeks without making one of the worst mistakes I ever made. I let Winnie out when I shouldn’t have in the late evening when the porcupines are all round the house. She went for one and got her face so full of quills there seemed nothing for it but to cloroform [sic] her to get them out…. But I over did the dose and killed her…. I can see now that I should have roped her whole body to a board and put her through without the cloroform. I wish you had been there to help me judge. It was a bad thing.

But Frost could not, as hard as he tried, keep the focus on sweet peas and dogs and other things Carol could confidently do. His son’s poems kept arriving:

I forgot to say I wish I had in one holder the whole set of your poems to look over when inclined. Would it be too much trouble to make a loose-leaf note book of them sometime this winter? The depth of feeling in them is what I keep thinking of. I’ve taken great satisfaction in your having found such an expression of your life. I hope as you go on with them, they’ll help you have a good winter in the midst of your family.

“Depth of feeling” would have upset Carol, since it obviously skirts the matter of the poems’ aesthetic accomplishment. It is also hard to imagine his being pleased at his father’s insistence that the poems remain a private comfort, a source of patience in, and with, his family. Then, in the second paragraph, this reprimand:

One thing I noticed in your hand written letter I never noticed before. You don’t use a capital I in speaking of yourself. You write i which is awfully wrong. You begin a sentence with a small i too. You mustn’t.

Richardson rightly finds in Frost’s harsh correction an anxiety about his son’s having “minusculed” himself, though the more pertinent concern was likely Carol’s grandiosity, which perhaps reminded Frost of his own but without the benefit of his great gift or his stoical temperament. Speaking of his friend, the English poet Edward Thomas, Frost once described something “melancholy about him” as different from his own ability to “mop just about anything out of my system.” The letters to Carol counsel a quiet, steady life, lived close to the mean. His son’s poems were symptomatic of an inner storm that the writing itself seemed only to exacerbate.

The letters to Carol represent Frost’s greatest sustained attempt to write without metaphor, nearly without style, to meet his interlocutor in a zone free of trope, figure, “form.” But those were Frost’s safe havens. As he wrote in “Education by Poetry,” a talk he gave at Amherst in 1930, “What I am pointing out is that unless you are at home in the metaphor, unless you have had your proper poetical education in the metaphor, you are not safe anywhere.” It was what he’d written to Untermeyer after Marjorie’s death: “Here we are…not yet placed safely in changed forms.” And yet “Cadmus and Harmonia,” the Arnold poem, was already a “changed form,” its comfort apparently real, its transformative power as tangible to Frost as Frost’s own poems have been to so many—have been to me.

The exquisite thinking about metaphor (literally “a carrying across,” as from one shore, or one mental state, to another) that we find in Frost’s work was worthless in managing his son’s impulses toward self-destruction. We are lucky to have this beautifully edited volume of Frost’s letters, the third of five, from a time when everything in his life broke. “I feel as though I was getting better able to make my slumps and blues shorter than they used to be,” Carol wrote, proud of mastering his “mistakes.” Eight years later, after Carol’s suicide, writing again to Untermeyer, Frost put it this way:

I took the wrong way with him. I tried many ways and every single one of them was wrong. Some thing in me is still asking for the chance to try one more…. He thought too much. I doubt if he rested from thinking day or night in the last few years.

And then either one of the cruelest or most compassionate things—it depends on how one hears the “sentence sound”—Frost ever wrote: “He was splendid with animals and little children. If only the emphasis could have been put on those. He should have lived with horses.”