In his opening address to the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow at the beginning of November, Boris Johnson evoked the end of a James Bond movie in which the hero is “strapped to a doomsday device, desperately trying to work out which colored wire to pull to turn it off, while a red digital clock ticks down remorselessly to a detonation.” His audience of politicians and diplomats from around the world responded to the analogy with the same excruciating silence that met all his bad jokes. But Johnson’s domestic allies in the Conservative Party surely appreciated its ironic humor. It was they who strapped their country to the doomsday device that is Boris Johnson. Like anyone who has even the most cursory knowledge of his career, they have been waiting for the big red clock to tick down to his inevitable detonation.

One way to get a flavor of Johnson’s current situation is to consider two meanings of the word “knowing.” It suggests, at its simplest level, comprehension, understanding, recognition. But in another guise it hints at a kind of private collusion, a shared agreement to pretend not to be aware of what is really going on. In Johnson’s case, both of these meanings have long worked together. Everyone recognized that he was never remotely fit to be prime minister. But a very wide group of people—those most strongly in favor of Brexit—enjoyed that feeling of complicity, of being in on the Boris joke.

In the last two months, however, these two meanings have gradually drifted away from each other. The subtle game of knowingness doesn’t work anymore. There is only the flat knowledge that England chose to be governed by a man who lies about everything, who has no principles and no care for other people, and who cannot govern himself, let alone a large and complex country.

I remember watching a film on Britain’s Channel 4 of a focus group made up of former supporters of the Labour Party in so-called Red Wall constituencies, in the Midlands, shortly before the general election of December 2019. Those taking part were asked what they thought of Johnson. They said things like “If he can lie to the queen, he can lie to anybody,” and called him “a buffoon to some extent, but…a lovable buffoon.” And they all said they were going to vote for him. The election results would suggest that they did—Johnson’s victory was won largely in these working-class areas. It would be misleading, and falsely comforting, to say the voters were fooled by him, that they thought he was a man of steely integrity and cool competence. The knowingness was not just an elite indulgence. It went deep.

When and why did it vanish? How does a lovable buffoon become merely a buffoon? Johnson’s discombobulation in recent weeks is not unreasonable—the change has come quickly and, from his point of view, without warning. There is a song, “Station Approach” by the British rock band Elbow, about wanting to “be in the town where they know what I’m like and don’t mind.” Johnson has always lived in that town, always had newspaper editors and magazine owners who know he lies to their readers but pay him a lavish salary anyway, lovers who know he is serially unfaithful but choose to believe his protestations of devotion, political allies who know that he is wildly incompetent but don’t mind so long as he can win elections. Why should all this change now?

Consider the things that did not seem to damage Johnson very much, if at all. In mid-October two House of Commons all-party committees issued a joint report describing Johnson’s slow and muddled response to the beginnings of the pandemic in March 2020 as “one of the most important public health failures the United Kingdom has ever experienced.” That did him no harm. Nor did the revelations that hugely expensive contracts for the procurement of medical devices and personal protective equipment for the National Health Service were awarded to Tory cronies who had no experience in supplying them. Nor the direct evidence of his former lover Jennifer Arcuri that Johnson, when he was mayor of London, offered to advance her business interests. Nor his flagrant abuse of patronage in appointing more cronies, including his own brother and the son of a Russian oligarch, to the House of Lords. He shrugged these things off, as he has always done, with the tacit, and perfectly reasonable, question: Well, what did you expect?

It’s actually quite funny that it all started to unravel for Johnson when he tried his hand at something that is patently out of character for him: loyalty. Johnson betrays people, causes, and allies whenever it suits him. For some strange reason, however, he decided to be faithful to Owen Paterson, a Tory member of Parliament, former cabinet minister, and fervent Brexiteer. While continuing to work as an MP, Paterson was receiving large payments from two private companies. This, remarkably enough, was within the rules. But the parliamentary commissioner for standards, Kathryn Stone, found that he had directly lobbied ministers on behalf of these companies, which is not. The commissioner recommended that Paterson be suspended from Parliament for thirty days.

Advertisement

Johnson, however, decided to come to Paterson’s rescue by instructing all Tory MPs to vote to overturn this finding and to weaken the whole system of ethical oversight by allowing MPs to appeal adverse rulings. This provoked a large-scale backlash from many of those MPs, forcing Johnson into ignominious retreat. Many of them were baffled that Johnson had squandered so much political capital merely to protect an ally from the consequences of his own breach of the most basic ethical standards. But the strong probability is that Johnson was also thinking of himself. There is an expectation that Stone will investigate the strange saga of the lavish refurbishment, by Johnson and his wife Carrie, of their private flat in Downing Street. Overturning Stone’s ruling on Paterson would, conveniently, have rendered her patently powerless or even forced her to resign.

The reason Johnson wanted to do this became obvious in mid-December when the Electoral Commission published a report on the failure of the Conservative Party to declare a donation from the Tory peer Lord Brownlow toward the cost of the designer upgrade. The report made it pretty clear that Johnson had lied about this too. Back in May, Johnson’s independent adviser on standards, Lord Geidt, cleared him of a conflict of interest over the donation from Brownlow, on the grounds that he appeared not to be aware of the arrangement. But the new report cites a WhatsApp message from Johnson to Brownlow in November 2020 asking directly for extra money for the redecoration.

Another lie—so what? Yet there’s something in this whole business that is particularly dangerous for Johnson. It touches the raw nerve of English society: social class. Johnson’s great strength, and the reason he was so crucial to Brexit, is that he managed somehow to transcend class. As a journalist in the 1990s, he drew snobbish caricatures of British working-class men as (to quote one of his Spectator columns) “likely to be drunk, criminal, aimless, feckless and hopeless.” But as a politician, he has had an extraordinary ability to project himself as both a toff (and thus to engage the old instincts of class deference) and an honorary member of the proletariat, a bit of a lad whose carefully arranged dishevelment could be interpreted as “not putting on airs and graces.”

The problem with spending £200,000 on rattan chairs and Lulu Lytle sofa covers for the Downing Street flat is that it pulls this fusion apart from both ends. The expenditure exceeds the average price of an entire house in a Red Wall area like Stoke-on-Trent, which reminds working-class voters that Johnson really is not one of them. But that might be okay if he did not have to beg donors for the money; that makes him not a toff, either. (True toffs don’t buy furniture—they inherit it.) It makes Johnson seem what he actually is—a middle-class opportunist on the make, very much putting on airs and graces. It negates the impulse toward deference among his voters while simultaneously scraping off the carapace of authenticity that Johnson built around himself by seeming not to care about appearances.

There’s another trick of language at work here. Playing fast and loose with money can be regarded as an aristocratic virtue, an expression of devil-may-care insouciance. But an invisible line divides devil-may-care and its dark and politically dangerous twin, sleaze. That word has a peculiar potency in British politics. It is a six-letter corrosive that strips the sheen of glamour from bad-boy antics. In recent years it seemed to have lost its currency, perhaps because it had sexual connotations that have been complicated by shifting attitudes. A search of Hansard, the record of parliamentary debates at Westminster, shows that it was used just five times in 2016, not at all in 2017, once each year in 2018 and 2019, and five times in 2020. But it has been uttered 131 times in 2021.

Those who deploy the word are, of course, Johnson’s political enemies, mostly in the Labour Party and the Scottish National Party, but it is telling that opponents feel suddenly emboldened to use it so often. Sleaze is a great reducer. It deflates sprezzatura into squalor and sordidness. And it retains something of its etymological origins: thin or flimsy in texture; having little substance. Neither of these meanings is good for Johnson, who is peculiarly vulnerable to both.

Advertisement

This is why it was especially idiotic for Johnson to identify himself so closely with Paterson’s moonlighting and greed. Anyone with any sense of British political history knows that the word “sleaze” acted like a curse on John Major’s Tory government of the 1990s, a malediction that, once uttered, cast a spell of doom that could never be broken. This was in spite of the fact that Major’s personal integrity was never questioned. Even more pertinent, though, is the scandal of 2009, when the details of expenses paid to MPs from the public purse (most memorably Sir Peter Viggers’s claim for the cost of installing a house for the ducks in his garden pond) were leaked, deepening an existing sense of disgust with the political system.

That sense of alienation from “the elites” in Westminster fed into the great rebellion of 2016: Brexit. If anyone should understand this, it is the embodiment and beneficiary of that project, Johnson himself. It is a mark of his strategic, as opposed to merely managerial, incompetence that he invited the casting upon himself of the hex of sleaze. Under the influence of that dis-enchantment, telling lies about how you begged for money to fund your dream interior does not look roguish. It looks slimy.

All of this still had, however, some degree of abstraction. It was Westminster business: donors, lobbyists, funny money. What made Johnson’s personality disorder explosive was the way it became, for most voters, personal, through two things that almost everyone in Britain cares deeply about: Covid-19 and Christmas. For most people in 2020, the most important family holiday of the year was a time of sadness, because many of their familiar gatherings and visits had to be canceled in the interest of public health. Johnson himself summed it up on December 19, 2020, when he warned people against the usual seasonal socializing: “We’re sacrificing the chance to see loved ones so we have a better chance of protecting their lives.”

The government-issued rules were clear: “You must not socialize with anyone you do not live with or who is not in your support bubble in any indoor setting.” There was an exception for work that was “reasonably necessary.” That did not mean office parties. Yet there were parties, lots of parties: in the fabulously refurbished Downing Street flat on November 13 (apparently to celebrate the departure of Johnson’s chief adviser Dominic Cummings), a small gathering with drinks in Downing Street at which Johnson made a short speech on November 27, a Christmas quiz for staff at which Johnson appeared virtually on December 15, and a larger and more raucous party downstairs in Downing Street on December 18 that Johnson did not attend but of which he must have been aware. In the unfolding of this story, two of Johnson’s most potent weapons—the power of the joke and his ability to hover between the real and the unreal—have turned against him.

There is, firstly, something almost too neat in the fact that what has accelerated Johnson’s appointment with doomsday is a laugh. It is, to be more precise, a leaked video of Allegra Stratton, the journalist brought into Johnson’s inner circle in October 2020 to impose some order on its chaotic communications. In the video, shot on December 22, 2020, she is rehearsing for Downing Street’s planned daily televised briefings (a plan soon abandoned). Other staffers are playing the roles of journalists. Johnson’s adviser Ed Oldfield asks her, “I’ve just seen reports on Twitter that there was a Downing Street Christmas party on Friday night. Do you recognize those reports?” And she laughs, the first of three warm, charming chuckles. The third comes when she says, “This fictional party was a business meeting, and it was not socially distanced.” These are not evil cackles or villainous guffaws. They are friendly laughs of knowingness, the signals that we here are all in on the joke. The problem is that considering the real sorrows that ordinary people were enduring, this idea too has crossed the invisible line between being in on the joke and being the butt of the joke, between having a laugh and feeling that you are being laughed at.

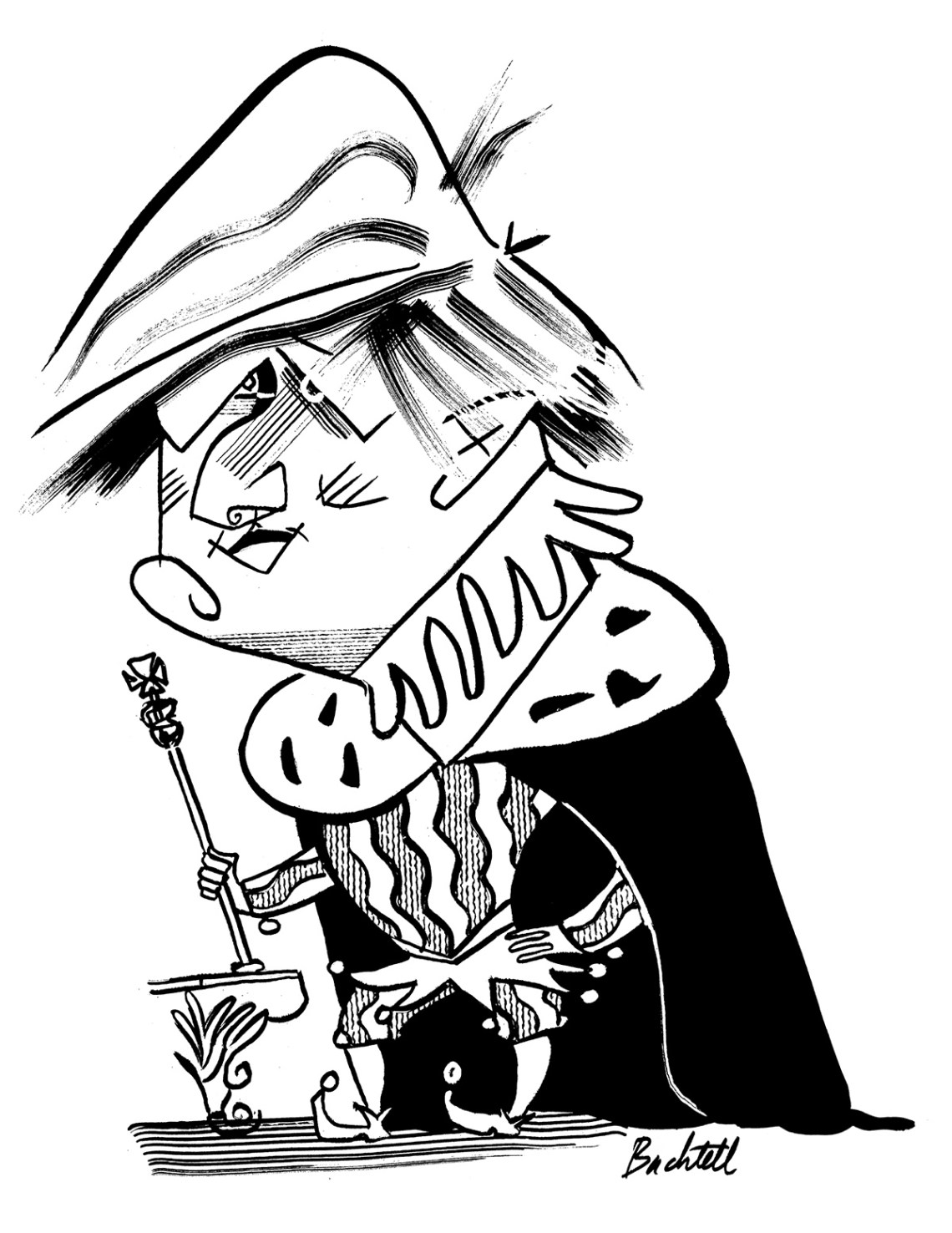

Johnson has always walked that line like a political Philippe Petit. His high wire has been strung between the poles of outrageous insult (almost always of people weaker and more vulnerable than him) and “Oh, for heaven’s sake, it was only a joke.” The idea of humor has been utterly essential to his success—it is the solvent in which a lie is merely an exaggeration, and a racist slur is merely a merry jape. Emmanuel Macron has reportedly described Johnson as “a clown,” and he was by no means the first to use the term. But successful clowns are very smart people, acutely aware that if they do not stay within the fuzzy boundaries of what the audience is finding funny, they become embarrassing and even frightening.

This fate was already creeping up on Johnson before the Stratton video emerged in December. The style that worked in front of already drunk corporate audiences when he was practicing his lucrative sideline as an after-dinner speaker does not impress when his listeners are sober and serious. The meltdown in November when he lost his place in a speech to the Confederation of British Industry, rambled into a long diversion about Peppa Pig World, a theme park based on the children’s cartoon character, and imitated the sound of an accelerating car with grunts that the official Downing Street press release transcribed as “arum arum araaaaaagh,” dramatized the moment at which the clown became both mortifyingly infantile and, for those who have to live in the pandemic-stricken country he governs, quite scary. When that happens, the collusive atmosphere that Johnson has been so good at creating—what does it matter so long as we’re all having fun?—rapidly evaporates. Johnson keeps playacting but his public (both within and outside of Westminster) stops playing along.

The other skill that Johnson wielded so deftly and effectively was the conjuring of what we might call nonreality. His career was built on his talent, as Brussels correspondent of The Daily Telegraph, for inventing stories about the madness of the European Union. These were not mere lies—Johnson had the ability to keep them suspended somewhere between existence and nonexistence, real enough to help shape his country’s fate yet always held up in the air by invisible quotation marks of knowing irony.

This way of shaping stories has now come back to haunt him. His tale about the Christmas bash is a classic Johnson narrative: the party, he claims, was not a party because all the Covid-related rules were obeyed, and since the rules said there could be no party, it wasn’t a party. This fits perfectly into Johnson’s familiar mode in which the relationship between the signifier and the signified is always fluid, always up for grabs. But his past success at pulling off this trick has entirely misled him this time. The right answer for his own survival was the simple one: there was a party, I wasn’t at it but I should have stopped it, and I’m very sorry. Instead he could only make things worse by offering people who were hurt and angry a stale rehash from his old repertoire of absurdities.

Shaping these responses to specific scandals is the slow waning of the glow from Brexit. Johnson’s little lies were folded into a bigger lie: that Britain could leave the EU without any real consequences. So long as he could hold that great deception aloft, Johnson’s petty deceptions were, for those who support Brexit, of minor account. Getting Brexit done—the slogan that won him the 2019 election—was a great test of honesty. As Brexit supporters saw it, they had made a contract in that referendum, and Johnson was the only man who would honor it. This made him, oddly, an honest man, even one they knew with certainty would “lie to anyone.” The problem, though, is that the contract was bogus. The pain-free Brexit it promised could not be delivered. The clearer this becomes, the more naked Johnson must appear.

Johnson’s behavior has made a mockery of his ability to tell the English public how they should behave in the face of the Omicron variant of Covid-19. His dithering and posturing cost many lives in 2020, and his undercutting of official advice and rules will undoubtedly do the same in 2022. His loss of authority on the management of the pandemic was evident on December 14, when almost a hundred of his own Tory MPs voted against his proposals for Covid passports for entry into nightclubs and other venues. (The proposal passed only with votes from the Labour opposition.) As Covid fatigue deepens, the evidence that their leader does not himself believe anything he says will make it ever more difficult for people in England to separate the vital messages from the wildly implausible messenger.

Johnson’s last hope lies in the paradox that he is a liar but no deceiver. Those who have the ability to bring him down—the powers that be in the Conservative Party—are those who raised him up, in full consciousness of what that meant for their country. It was they who set the big red digital clock ticking down toward the chaotic finale. Only their reluctance to acknowledge this responsibility is delaying the approach of zero hour for Boris Johnson.

—December 16, 2021

This Issue

January 13, 2022

The House That Johns Built

Who Does Éric Zemmour Speak For?