In the late 1870s, a new type of hero arose in Russia. “Upon the horizon there appeared a gloomy form, illuminated by a light as of hell…with lofty bearing, and a look breathing forth hatred and defiance,” explained Sergei Stepniak in Underground Russia: Revolutionary Profiles and Sketches from Life (1882). This hero, who “made his way through the terrified crowd to enter with a firm step upon the scene of history,” was the terrorist: “Noble, terrible, irresistibly fascinating…he combines in himself the two sublimities of human grandeur: the martyr and the hero.”

Stepniak was himself a terrorist who in 1878 had assassinated the head of Russia’s secret police by stabbing him and twisting the knife in the wound. He escaped abroad. His “revolutionary portraits” of assassins (he calls them “saints”) celebrated the People’s Will movement, which culminated in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Infiltrated by a tsarist double agent, the People’s Will had collapsed by 1883, with the arrest of its legendary leader Vera Figner. Terrorism abated, only to reach unprecedented heights two decades later.

Terrorism practically defined the early twentieth century in Russia, the first country where “terrorist” became an honorable, if dangerous, profession, one that could be passed down in families for generations. Its extent was breathtaking. As Anna Geifman observes in her authoritative 1993 study Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894–1917:

During a one-year period beginning in October 1905, a total of 3,611 government officials of all ranks were killed and wounded throughout the empire…. By the end of 1907 the total number of state officials who had been killed or injured came to nearly 4,500. The picture becomes a particularly terrifying one in consideration of the fact that an additional 2,180 private individuals were killed and 2,350 wounded in terrorist attacks between 1905 and 1907…. From the beginning of January 1908 through mid-May of 1910, the authorities recorded 19,957 terrorist attacks and revolutionary robberies, as a result of which 732 government officials and 3,051 private persons were killed.

Polite society celebrated terrorists, who included the first suicide bombers. Killing and maiming (throwing sulfuric acid into the face) evolved into a sport in which victims, Geifman explains, were just “moving targets.” In 1906–1907 a group of terrorists, or “‘woodchoppers’…as one revolutionary labeled them…competed…to see who had committed the greatest number of robberies and murders, and often exhibited jealousy over others’ successes.” One anecdote told of an editor who was asked if his newspaper would run the biography of the new governor-general. “No, don’t bother,” he replied. “We’ll send it directly to the obituary department.”

After 1905 terror became so commonplace that newspapers “introduced special new sections dedicated exclusively to chronicling violent acts…[with] daily lists of political assassinations and expropriations [robberies] throughout the empire.” In Warsaw, revolutionaries threw explosives, laced with bullets and nails, into a café with two hundred people present, in order “to see how the foul bourgeois will squirm in death agony.” “Robbery, extortion, and murder,” Geifman notes, “became more common than traffic accidents.”

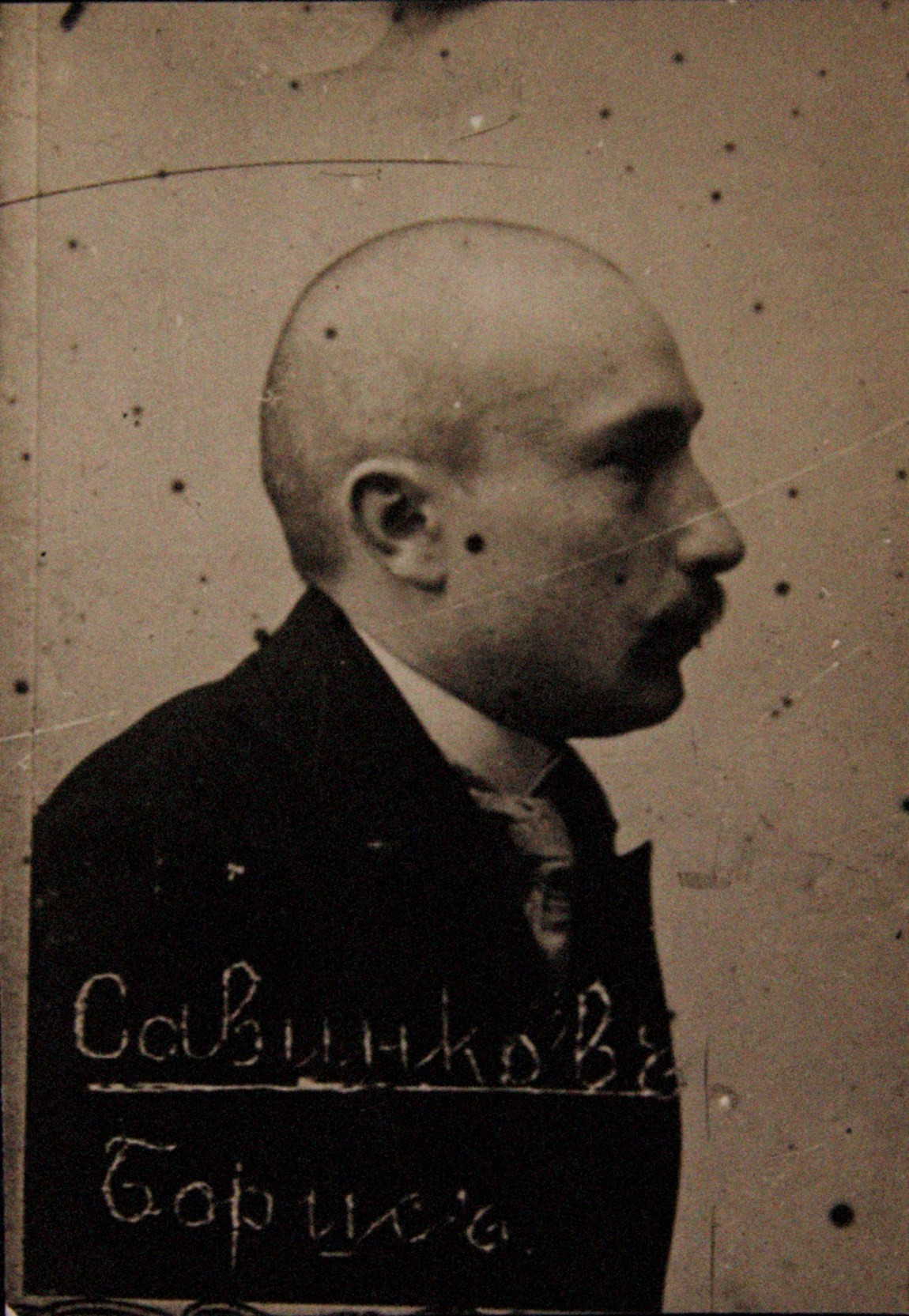

Stepniak’s mythic portraits of terrorists found many imitators. Like Stepniak, Boris Savinkov practiced the epoch’s two most prestigious Russian occupations, terrorism and novel writing. Citing Winston Churchill’s overstated observation about Savinkov that “few men tried more, gave more, dared more, and suffered more for the Russian people,” and applying W. Somerset Maugham’s comment that “there is no more sometimes than the trembling of a leaf between success and failure” to Savinkov’s attempts to drive the Bolsheviks from power, Vladimir Alexandrov’s new biography of Savinkov, To Break Russia’s Chains, presents him as a secular saint who “chose terror out of altruism.” Alexandrov, a prominent scholar of Russian literature who grew up in a Russian émigré family, is best known for his writings on Nabokov and for The Black Russian (2013), a biography of an African American named Frederick Bruce Thomas, who became a wealthy entrepreneur in tsarist Russia and, after the Bolshevik takeover, in Turkey.

There is no doubt that Savinkov was the best known of early twentieth-century Russian terrorists. The son of a Russian imperial justice of the peace, he impressed others with his worldly polish, charming conversation, good looks, and elegant dress. A lifelong dandy, he had a taste for role-playing and was a master of disguises. In the 1904 campaign in St. Petersburg that resulted in the death of Interior Minister Vyacheslav von Plehve, Savinkov, without knowing any English, proudly pretended to be an English businessman named George McCullough. Joining the Combat Organization of the Party of Socialist Revolutionaries (PSR), he became its second leader.

Strangely enough, ideology didn’t interest him. Perhaps the most interesting feature of his Memoirs of a Terrorist is the almost total absence of concern for alleviating people’s suffering. He was not alone. In the memoirs of other terrorists, and in Savinkov’s descriptions of them, concern for the people is often a decidedly secondary matter. Vera Zasulich, whom Stepniak celebrated as the “angel of vengeance,” recalled how, as a girl, she wanted to die as a Christian martyr. Losing her faith, she sought a different martyrdom. “Sympathy for the suffering of the people did not move me to join those who perished,” she explained. Growing up at Bialkovo, an estate in Smolensk province, “I had never heard of the horrors of serfdom…and I don’t think there were any.” Savinkov ascribed a similar morbid psychology to terrorist Dora Brilliant, who demanded to be an actual bomb thrower. “No, don’t talk…I want it,” he quotes her. “I must die.”

Advertisement

Savinkov cites the letter the terrorist Boris Vnorovsky wrote to his parents before he died throwing a bomb: “Many times, in my youth, I had the desire to end my life.” In terrorism he found a way to do it. He was resolved on death, and all that “remained to be done was to find a definite program.” The terrorist Fyodor Nazarov was equally “far removed from acceptance of any party program,” Savinkov notes. Instead of loving the common people, “he developed a contempt for the masses.”

Savinkov irritated PSR leader Victor Chernov when—“with a chuckle,” in Alexandrov’s words—he expressed indifference to the party’s defining commitment to the peasantry. At times he pronounced himself an anarchist, Chernov noted, and at other times a devotee of “spiritual-religious revolutionism.” According to Alexandrov, a woman Savinkov tried to recruit for terror “concluded that terrorism for its own sake had eclipsed all other considerations for Savinkov.”

Chernov and others reached the same conclusion about Savinkov’s motives. What attracted him to terror was its risk, adventure, and the sheer thrill of dramatic murder. The hero of Savinkov’s novel Pale Horse, George—the English name Savinkov himself had adopted—finds this thrill addictive. “What would I be doing if I were not involved in terror?” he asks himself. “What’s my life without struggle, without the joyful awareness that worldly laws are not for me?” The hero of another novel by Savinkov, What Never Happened, explains, “I live for murder, only for murder.” He realizes that “he had fallen in love, yes, yes, fallen in love with terror.” Savinkov quotes his real-life bomb maker Alexey Pokotilov: “I believe in terror. For me the whole revolution is terror.”

Savinkov changed the Combat Organization’s preferred weapon from guns to bombs, which, of course, were much more likely to kill bystanders. In one successful assassination, a coachman died, in another the target’s fellow passenger. Having successfully blown up von Plehve in 1904 and the tsar’s brother Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich the following year, Savinkov acquired an aura of mysterious power.

Savinkov began his two careers, writer and terrorist, at about the same time, and, according to the scholar Lynn Ellen Patyk, he kept clippings about both. Did Savinkov write novels to glorify his career as a terrorist or did he turn to terrorism to provide compelling material for fiction? In either case, he engaged assiduously in a process that Russians call “life creation,” a form of self-mythologization in which one lives as if one were a literary exemplar. “As a member of the gentry, a cosmopolitan aesthete, and a dandy,” Patyk persuasively argues, “Savinkov embraced a model of authorship bequeathed to Russian literature by…Lord Byron and nativized by Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov, all of whom remained among Savinkov’s favorites.”

Betrayed by a double agent, Savinkov was arrested but staged a thrilling prison escape, aided by a guard who was a secret Socialist Revolutionary and who tried to put other guards to sleep by feeding them morphine-laced candy; when that failed he had Savinkov impersonate a guard. Savinkov then went abroad, where he became a Russian nationalist. When World War I broke out, Chernov and other socialists declared neutrality in this war among imperialists, but Savinkov agitated against the hated Germans. The February 1917 revolution allowed him to return to Russia, where he joined the Provisional Government and served in several roles, including director of the Ministry of War. He supported General Kornilov, who aspired to authoritarian military rule, and opposed the Bolsheviks both before and after their October 1917 coup. For many years, Savinkov was the Bolsheviks’ most implacable foe.

He joined or founded various anti-Bolshevik groups—once again, ideology didn’t matter. Writing to his friend the poet Zinaida Gippius, he declared, according to Alexandrov, that henceforth “he would work with anyone, of any political persuasion.” And he would not be fastidious about means, either. “Dealing with Bolsheviks brought out a cruel streak in him,” Alexandrov concedes. The Polish leader Józef Piłsudski convinced Savinkov to set up an anti-Bolshevik detachment on Polish soil and joined forces with the rogue general Stanislav Bulak-Balakhovich, who conducted mass pogroms in the Pale of Settlement. According to Alexandrov, Savinkov

Advertisement

condemned the pogroms and confessed that they made him feel personally ashamed. However, he also tried to explain—but not excuse—their origin and concluded that “the peasant, the Red Army soldier and the follower of Balakhovich perceives the Jew as an enemy, as a true ally of the Reds. From this comes the hatred—that blind, unreasoning, spontaneous anti-Semitism that falls like a black spot on Balakhovich’s glory.

It’s a rather qualified “condemnation.”

Savinkov’s National Union for the Defense of the Motherland and Freedom conducted raids into Bolshevik territory during which, according to Alexandrov,

no method was off limits, at least in theory, and at one point the GPU [secret police] claimed that captured members of the National Union were found to have large quantities of potassium cyanide that they were planning to use to poison the most loyal Red Army units.

Sergey Pavlovsky, the National Union’s military chief of staff in Warsaw, displayed special brutality. Following Savinkov’s orders, he conducted a five-month campaign of armed attacks and robberies during which he and his band apparently killed more than sixty people and “carried out bloody outrages against Bolshevik Party members, including torture.”

Using his charming conversational and acting abilities, Savinkov secured support for the White Army throughout Western Europe, impressing Somerset Maugham, Churchill, and the famous “ace of spies,” British secret agent Sidney Reilly. Savinkov even met with Mussolini, who suggested that the Russian “join him in fighting communism in Italy,” Alexandrov explains. “This was not what Savinkov came for, but he agreed.”

Fascism may have been the only ideology that appealed to Savinkov. Defending Mussolini, Savinkov insisted that “fascism saved Italy from the commune” and that “the so-called imperialism of the Italian fascists is an accidental phenomenon that can be explained by an excess population in the country and the absence of good colonies.” Still deeper reasons made the movement attractive. “Fascism is close to me psychologically and ideologically,” he wrote. “Psychologically—because it stands for action and total effort in comparison to the lack of will and the starry-eyed idealism of parliamentary democracy,” and ideologically because “it stands on a national platform” and relies on the peasantry for support.

The most dramatic events lay ahead. Hoping to assassinate Bolshevik leaders, he communicated with his supporters behind enemy lines. Unfortunately, the group he trusted had been created by the Bolsheviks to lure him back to Russia. When Savinkov returned, he was promptly arrested. And then, amazingly enough, this implacable foe of the Bolsheviks joined them. Renouncing his former professed beliefs, he proclaimed at his trial, “If you are Russian, if you love your motherland, if you love your people, then bow to the workers’ and peasants’ rule and acknowledge it without reservation.”

And so Savinkov became a Bolshevik propagandist. “This change in Savinkov’s attitude,” Alexandrov comments, “is so improbable that it could be compared to the pope of Rome suddenly professing admiration for Satan.” The shock in the West was profound. At first Reilly defended Savinkov, but at last he branded him “a renegade, the likes of which world history has not known since the time of Judas.”

The Bolsheviks treated their turncoat well. Commuting his death sentence to ten years, they placed him in a luxurious apartment—albeit one within Lubyanka Prison. Even before his public confession at his trial, Savinkov demanded (and received) a range of personal comforts, including two sets of silverware, cigarettes, books, writing materials, and beer. After the trial, his mistress lived with him, he met writers and friends, and agents of the OGPU (as the GPU was now called) took him on excursions to the theater, restaurants, and parks. Soviet journals published three of his stories depicting Russian émigrés in an unflattering light.

And then, in 1925, quite unexpectedly, Savinkov died at the age of forty-six. According to the official account, which Alexandrov believes Soviet archives confirm, Savinkov committed suicide by leaping from a window. Needless to say, others have rejected this story because of its dubious source, because his mistress denied it, and because he had told his son Victor during a visit, “If you hear that I’ve laid hands on myself—don’t believe it.” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn claimed that a dying former agent with the Cheka, the first Soviet secret police organization, told him he had participated in defenestrating Savinkov. Alexandrov does not mention Semyon Ignatiev, Stalin’s last director of internal security, who recalled that, during the so-called Doctors’ Plot of the early 1950s, in which Jewish doctors were accused of planning to poison Soviet leaders, Stalin demanded that torture be used to make the doctors confess: “‘Beat them!’—he demanded from us, declaring: ‘what are you? Do you want to be more humanistic than LENIN, who ordered [Cheka director Felix] DZERZHINSKY to throw SAVINKOV out a window?’”

How Savinkov died is crucial to the very purpose of Alexandrov’s book: to exalt the Russian terrorist movement in general and Savinkov in particular. “The [PSR] assassins called themselves ‘terrorists’ proudly, but what they meant by this bears no resemblance to what the word means now,” Alexandrov argues. The difference, he maintains, is that today’s terrorists kill people randomly and “attack almost any national, social, or cultural group chosen by chance and engaged in any pastime, with the more victims the better…. Had the Socialist Revolutionaries known of such events, they would have condemned them as unequivocally criminal.”

As Geifman’s account demonstrates, however, the SRs behaved similarly to modern-day terrorists. “By 1905, terror had indeed become an all-pervasive phenomenon, affecting every layer of society,” she writes, and “the PSR provided…a fresh justification for their deeds.” In contrast to earlier terrorists, the PSR “allowed its members to exercise terrorist initiative freely and in the periphery.” Soon enough there developed what the liberal politician Peter Struve called a “new type of revolutionary,” “a blending of revolutionary and bandit [marked by] the liberation of revolutionary psychology from all moral restraints.” As the historian Norman Naimark observed, terrorism became for them “so addictive that it was often carried out without even weighing the moral questions posed by earlier generations.” In Geifman’s words, it entailed “robbing and killing not only state officials but also ordinary citizens, randomly and in mass numbers.”

Like other recent historians, Geifman seeks “to demystify and deromanticize” the Russian terrorist movement. Those she calls “far from impartial memoirists”—including Stepniak and Savinkov—created a myth of humane, high-minded, noble, and reluctant terrorists and of “selfless freedom fighters.” It was common “to use lofty slogans to justify what in reality was pure banditry,” and often much worse. Soon enough, sheer sadism became routine. “The need to inflict pain was transformed from an abnormal irrational compulsion experienced only by unbalanced personalities into a formally verbalized obligation for all committed revolutionaries,” Geifman explains. Some victims were thrown into vats of boiling water; others were mutilated both before and after death.

Conscious mythmaking prevailed from the movement’s beginning. In his highly influential Historical Letters (1868–1870), the social philosopher Peter Lavrov, who wrote a preface to Stepniak’s Underground Russia, called for “critically thinking individuals” to arouse the unenlightened masses by fabricating heroic myths. “Martyrs are needed, whose legend will far outgrow their true worth and their actual service,” Lavrov foresaw. “Energy they never had will be attributed to them…. The words they never uttered will be repeated…. The number of those who perish is not important: legend will always multiply it to the limits of possibility” so as to “compile a long martyrology.”

For Alexandrov, the noblest, most spotless of all these heroes is Savinkov. To Break Russia’s Chains begins, “This is the story of a remarkable man who became a terrorist to fight the tyrannical Russian imperial regime, and when a popular revolution overthrew it in 1917 turned his wrath against the Bolsheviks because they betrayed the revolution and the freedoms it won.” His motives, Alexandrov believes, were entirely pure: “All his efforts were directed at transforming his homeland into a uniquely democratic, humane, and enlightened country.”

Accusations that Savinkov loved terror itself, Alexandrov concludes, “are profoundly unfair because they are the result of ideological bias, not historical or psychological understanding.” In Alexandrov’s view, Savinkov “chose terror out of altruism, although what he did bears no resemblance to what ‘terrorism’ means today.” For that matter, Alexandrov repeats, although Savinkov organized terror, “he never killed anyone himself.” Is someone not a killer if he planned, organized, and provided weapons for murder but, rather than throwing bombs himself, instead recruited others to do so?

Alexandrov stresses an incident figuring prominently in terrorist mythology. When Savinkov’s recruit and childhood friend Ivan Kaliaev was about to throw a bomb at the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich’s carriage, the presence of the duke’s wife and children made him draw back, because the Socialist Revolutionary Party had issued no instructions about this (not unforeseeable) possibility. Believe it or not, Savinkov writes matter-of-factly, the party “had never discussed or even raised the question” of killing family members. Savinkov recalls telling Kaliaev that killing innocents “was quite out of the question,” evidence for Alexandrov that his hero was supremely considerate of innocent human life.

Alexandrov is correct that Savinkov did not deliberately target innocent people, as other terrorists did, but if he was so concerned about not harming bystanders, why did the Combat Organization under his direction switch from guns to bombs? And why did Savinkov’s bomb makers construct their weapons not in remote buildings but in hotels, where, on two occasions, they accidentally exploded? After Pokotilov, whose heavy drinking should have been a warning sign, blew himself up in the Northern Hotel in St. Petersburg, Maximilian Shveytser died when an accidental explosion destroyed his room, several adjoining ones, and a French restaurant. Lumber, plaster, and furniture landed on the street below. Savinkov even cooked up the scheme of using an early (and hard-to-manage) airplane carrying a giant bomb. “One wonders what precautions Savinkov believed he could take to spare the lives of innocents,” Alexandrov asks. What indeed.

Although he barely mentions the indiscriminate carnage Geifman describes, Alexandrov does note the attempt of the Maximalists—an offshoot of the PSR too violent even for them—to kill the tsar’s chief minister, Pyotr Stolypin, by bombing his house when it was crowded with petitioners. Twenty-seven people were killed, and about thirty others—including Stolypin’s daughter and son—were wounded, some seriously. The minister escaped with minor injuries. Is this an example of the targeted killing that bears no resemblance to modern terrorism?

“Savinkov and [his mentor Mikhail Gotz] rejected what the Maximalists had done,” Alexandrov assures us, “because of the horrifying number of innocent victims”—which sounds as if they were shocked by the deaths of bystanders rather than the setback to propaganda. Yet in his memoirs, Savinkov reports his own reaction to the PSR’s official “proclamation repudiating the terror of the Maximalists”:

I did not approve of it. Gotz expressed sympathy for the Maximalists. He was sorry for them, pointing out that the explosion…had not been carefully prepared…. Gotz also pointed out that the killing of many innocents was bound to have an adverse effect on public opinion. He refrained, however, from passing judgment on the Maximalists. The explosion…was the only possible answer to [the tsar’s] dissolution of the Duma.

Savinkov reports that he tried to join forces with the Maximalists. Once again, ideology made no difference to him. “Look here, we’re talking man to man,” he recalls telling the Maximalist leader.

Why cannot we work together? For my part, I see no obstacles. It is all the same to me whether you are a Maximalist, an anarchist, or Socialist Revolutionist. We are both terrorists. Let us combine our organizations in the interests of terror.

Are statements like this why so many have concluded that Savinkov was primarily motivated by terror itself?

Most studies of Savinkov focus on his novels, especially Pale Horse. An early English translation by Z. Vengerova (known to Churchill) has been far surpassed by the sparkling new one by Michael Katz, who has ably translated several works of Russian radical fiction—including Vasily Sleptsov’s Hard Times and Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s utopian novel What Is to Be Done? In his 562-page biography, Alexandrov devotes only six pages to Pale Horse, and there he mostly denies that the work expresses Savinkov’s real views. To present Savinkov as an altruistic hero, Alexandrov could hardly do otherwise, since the novel has always been taken, in the historian Aileen Kelly’s words, as a “savage demystification” of the terrorist hero.

Pale Horse includes conversations about the morality of terrorism. Curiously, they concern not whether terrorism is justified but which justification is best. The Christian Vanya, evidently based on Kaliaev, reasons that even though Christians should not kill, he is a bad Christian and so is bound to do so. In one shocking passage, the hero George describes how in the Belgian Congo, Africans who lived on one side of a river would kill those who wandered over from the other shore, and vice versa. He concludes that killing is normal: “I want to do something and I do it. Does this [need for justification] perhaps hide some cowardice, fear of someone’s opinion?” When Vanya asks how George can live without love, he answers, “You spit at the whole world.”

George at last murders his lover’s husband. “There is no distinction, no difference. Why is it all right to kill for the terror,” he asks rhetorically, “but for oneself—impossible? Who will answer me?” Like the protagonist of Lermontov’s Byronic novel A Hero of Our Time, after the murder George immediately loses interest in his lover. Alexandrov asserts that George’s “aimless egoism has no relation to anything that mattered most deeply to Savinkov personally,” but even if this is true, the book surely glorifies the Byronic self-image Savinkov labored to construct.

One might suppose that Savinkov’s willingness to join the Bolsheviks would shake Alexandrov’s certainty that his subject was not an adventurer but a man of principle. Alexandrov instead constructs a scenario rescuing his hero’s reputation. He surmises that Savinkov must have been deceiving the Bolsheviks so that they would eventually free him and give him another chance to kill their leaders. Even if the Bolsheviks had eventually freed Savinkov, is it remotely plausible that the Cheka would allow him to roam unmolested and build a new terrorist organization? Given Savinkov’s “absolute commitment to personal and political freedom,” Alexandrov reasons, his death must have been suicide prompted by the realization that he would never be released to carry out his scheme. Having “lost his gamble,” his suicide was “the only blow he could make against” the regime.

In contrast to Savinkov and many others, Lenin despised those who romanticized terror. They suffered, he wrote, from “petty-bourgeois revolutionism,” “dilletante-anarchist revolutionism,” and, most famously, an “infantile disorder.” “The greatest danger…that confronts a genuine revolution,” he declared, “is exaggeration of revolutionariness…when they begin…to elevate ‘revolution’ to something almost divine.” It is no wonder that Lenin triumphed, since his grasp of power politics was never obscured by dreamy idealizations.

One sympathizes with Alexandrov’s wish that tsarism could have been replaced by something other than Bolshevism. Savinkov, he believes, came a hairsbreadth from ensuring just that. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Nadezhda Mandelstam posed a different question: Could it be that the romanticization of terror and revolution is the main reason Russia followed its lugubrious path?