When Barack Obama was campaigning for Joe Biden in 2020, he spoke at an event in a gymnasium in Michigan. As he was leaving, someone bounce-passed a basketball to him. From deep in the corner, he tossed up a shot, and it went in. People yelled, “Whoa-whoa-whoa-whoa-whoa!” and “All net!” What former president—what national political figure of any kind—had ever hit a walk-off three-pointer, and with the cameras watching? Amazing! Unheard of! Millions later saw the video online. In a karmic sense, the Democrats won the election right there.

I propose this important moment as an analogy to stand-up comedy. Making an audience laugh hard, without coercion or restraint—it’s a walk-off three-point moment, an epiphany of accuracy, coolness, and style. The pure high of it must be one of the greatest feelings in the world.

Kliph Nesteroff, a longtime student of comedy, has written two books about this fateful thrill and occupation. The more recent one, We Had a Little Real Estate Problem: The Unheralded Story of Native Americans in Comedy, turns to a subject that even some who work in comedy might know nothing about. Today about a hundred young men and women from many North American tribes are writing TV and sketch comedy and performing stand-up and improv, remuneratively or not. The Navajo comedian Ernie Tsosie says, “Now almost every tribe has a comedian.”

One question might be: Is there something in particular about coming from a Native background that makes a person want to write and perform comedy? Nesteroff mentions the Native tradition of the sacred clown, called heyoka by the Lakota, Nanabozho by the Ojibwe, and Wesakaychak by the Cree. The clowns, sometimes known as “contraries,” did things backward in everyday life and showed the comical side of their societies. As Adrianne Chalepah, a Kiowa Apache comedian, explains:

It can feel sometimes like our communities are in a constant state of mourning, like there aren’t enough tears to cry about every single tragedy. Being able to laugh is important. Native humor is part of why we survived. It’s allowing yourself to feel a little bit of joy in a moment that might otherwise break you.

Doing stand-up comedy takes nerve, whatever one’s culture or background (public speaking is one of the most common fears), and stories of individual bravery and hero tales have always been part of tribal cultures. Long before Sitting Bull became a featured member of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, he was famous for his many brave deeds. In a skirmish with the army escort of a party of railroad surveyors in the Yellowstone valley, Sitting Bull sat down within range of the soldiers’ rifles and smoked a pipe while bullets flew. A few fellow warriors joined him and passed the pipe. When it was done, the others got up and ran. Sitting Bull walked. Stand-up comedy seems like a modern-day version of that—maybe one reason Native people admire it.

In We Had a Little Real Estate Problem, Nesteroff goes back to Native performers from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Some of them ended up in Wild West shows through an agreement between the government and impresarios like Buffalo Bill; sometimes the choice was to join the company or go to jail. The Office of Indian Affairs placed others in medicine shows, where they provided a backdrop for peddlers of fake Native cures and sometimes did ethnic-comedy sales pitches. The first Native satirist in print was a Muscogee Creek named Alexander Posey, who used the pseudonym Fus Fixico. He wrote a column in Indian dialect for a tribal newspaper in which he made fun of the doings of the federal bureaucracy (a subject Native people know more about, usually, than do non-Natives, because of the tribes’ unique, nation-to-nation relationship with the federal government). For example, Posey mocked the forced anglicization of Native names, saying that a “name like Sitting Bull or Tecumseh was too hard to remember and don’t sound civilized like General Cussed Her.” Between 1902 and 1906 he wrote seventy-two humorous columns as Fixico for the Eufaula Indian Journal, in what’s now Oklahoma. These caught the attention of a promoter, who arranged for him to join a national lecture tour. Before he could, however, Posey/Fixico drowned while crossing a flooded river near his house, and so he did not get a chance to be the first Native American stand-up comedian.

That honor goes indisputably to Will Rogers, a Cherokee whose image now adorns postage stamps, a huge mural overlooking downtown San Bernardino, California, and the airport in Oklahoma City, which is named for him; he has joined Mark Twain in the sparsely populated pantheon of beloved old-time humorists. Nesteroff fills in some details of the Rogers family’s history. Before the Cherokee were driven out of Georgia and North Carolina along the Trail of Tears to Indian Territory, Rogers’s grandfather, Robert, was among the minority of tribal members who took a buyout from the government. This angered the majority who resisted. Like some other Native people in the South, Robert Rogers owned Black slaves. He established a ranch in the Cherokee Nation, in the northeastern corner of what’s now Oklahoma, and prospered. In 1842 he was murdered by Cherokee vigilantes. His son, Clem, Will Rogers’s father, inherited the ranch and the enslaved people, whom he freed provisionally during the Civil War, though he fought for the South.

Advertisement

Will, born in 1879, could do miracles with a lariat, like someone hitting three-point shots on every try. As a rodeo cowboy, he could catch all four feet of a running horse with four ropes simultaneously and bring it to a stop. When he moved from rodeo to vaudeville, Rogers became a lariat-twirling star. For a while his horse accompanied him on stage. Then he began interspersing his act with jokes and dispensed with the sidekick. As a humorist and a wry, smarter-than-he-looks cowboy type, Rogers appeared on radio and in movies, and wrote a syndicated newspaper column five days a week that drew 40 million readers. Today no commentator has the level of national reach that Will Rogers had, but even in the best periods of his career, he fell into deep depressions. He never forgot the evil that had been done to the Cherokee or forgave President Andrew Jackson for setting in motion the Trail of Tears; Rogers sometimes expounded on those subjects, to the discomfiture of white observers.

I knew about Rogers’s wit (“I am not a member of any organized political party—I am a Democrat”; “Common sense ain’t common”; “Never miss a good chance to shut up”), and of course I remember that he never met a man he didn’t like; but I had not given much thought to his family’s slave-owning past, or how it might have influenced him. Nesteroff’s description of Rogers’s final two years was news to me. On his radio show in 1934, while introducing “The Last Round-Up,” a traditional cowboy song, Rogers described its melody as “really a nigger spiritual.” He repeated the word three times during the broadcast. The Pittsburg Courier, a leading Black newspaper, called it an “unwarranted and vicious insult to 12,000,000 Negroes” that “also shocked countless thousands of white radio listeners.” Blacks boycotted his sponsor (Gulf Oil) and his movies. Rogers responded with non-apologies that made things worse. He didn’t see why the word offended anybody. He said millions of white southerners used the word all the time and were the truest friends the race had.

Nesteroff suggests that a connection existed between this controversy and Rogers’s subsequent escape into flying, his favorite pastime. In August 1935, while on a pleasure jaunt with Wiley Post, the famous one-eyed aviator known for his carelessness, Rogers died in a crash near the Alaskan Native village of Barrow. His abrupt and sad end wiped out any memory of the still-recent outrage he had caused. Will Rogers’s death became the biggest news story of the year, and as Nesteroff says, “The complex and nuanced Cherokee comedian was reduced to a simple, homespun cowboy, representing God and country…. A myth was created that has endured for nearly a century.”

The book jumps around chronologically, as the early chapters on Fixico and Rogers alternate with ones about Native comedians of the more recent past and the present. It also hopscotches North America geographically. One of its pleasures is reading about the places in which the present-day comedians first heard the call. For Dakota Ray Hebert, a Dené of the English River First Nation, it happened in the town of Meadow Lake in northwestern Saskatchewan, where she listened to tapes of Bill Cosby on her Walkman. Adrianne Chalepah, the Kiowa Apache, often watched Monty Python’s Flying Circus with her family while moving between small Oklahoma towns like Anadarko and Cache. In the pulp and paper mill town of Fort Frances, Ontario, north of the Red Lake and Leech Lake Reservations, Ojibwe comedian Ryan McMahon remembers as a child seeing the grown-ups laughing at Eddie Murphy’s Delirious. The experience “sent [him] on the trajectory” that led to a life in comedy.

Drew Lacapa, son of a White Mountain Apache father, herded cattle with his five brothers near Whiteriver, Arizona, and watched The Carol Burnett Show and The Red Skelton Hour. Also from Arizona, Sierra Teller Ornelas, a self-described “sixth generation Navajo tapestry weaver,” whose family lived “rug to rug,” remembers watching videocassettes of Richard Pryor, George Carlin, Steve Martin, Johnny Carson, and Saturday Night Live while her mother wove. Ornelas went on to become a writer and producer of sitcoms in Los Angeles. Unfortunately, we’re not told what in particular about, say, Murphy’s or Burnett’s comedy attracted these devotees.

Advertisement

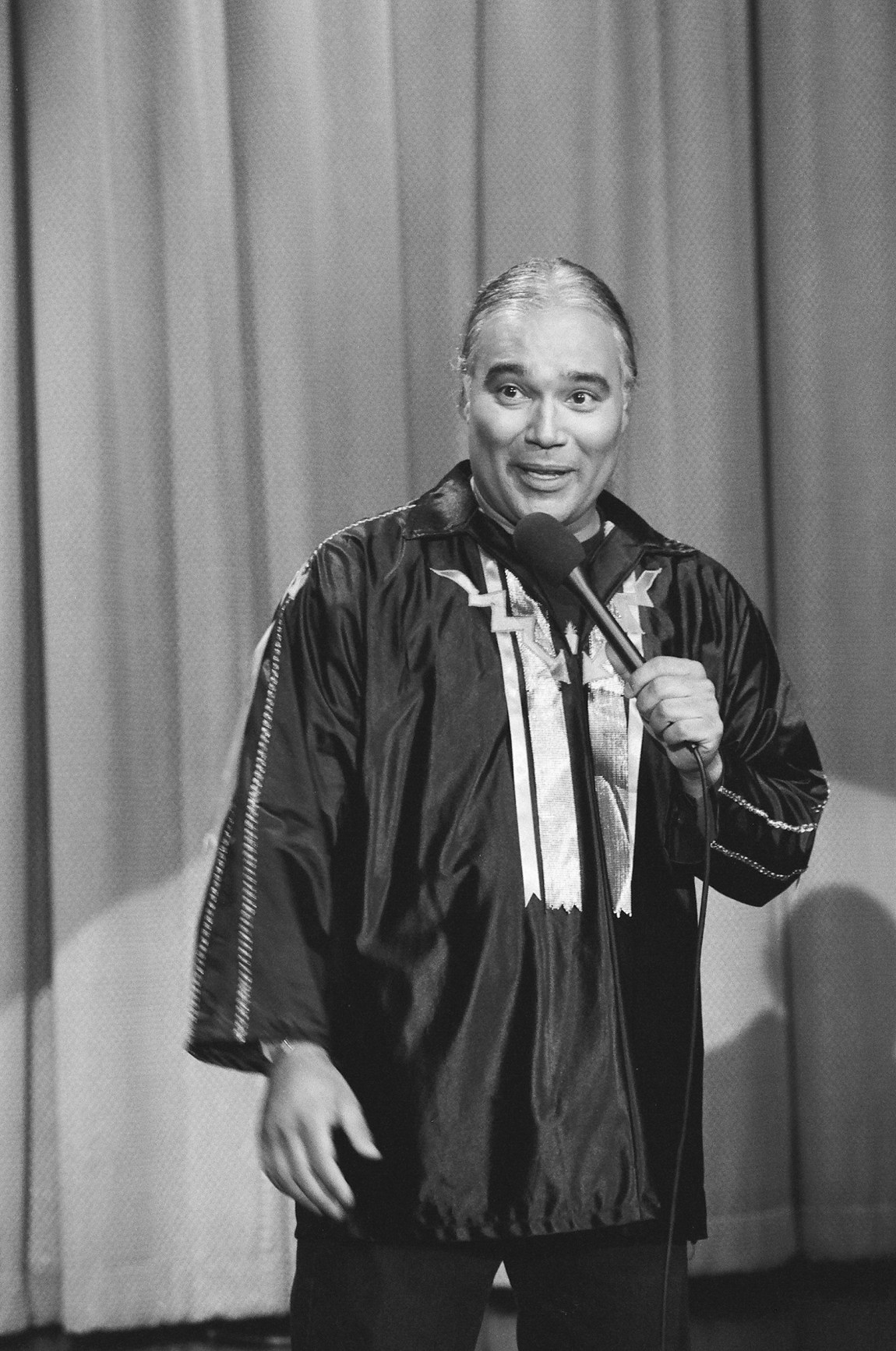

Charlie Hill, the most successful Native American comedian of the network-TV era, who performed on The Tonight Show, Late Night with David Letterman, and The Richard Pryor Show, and in various specials, came from the Oneida Reservation in northern Wisconsin. On Saturday nights his family would go to the Oneida Mission to take showers and then come home and watch Jackie Gleason. In a radio interview, Hill said, “That’s when it kind of set in…. I loved watching Jackie Gleason.” When his mother watched Jack Paar, past his bedtime, he would look on from behind a door and wonder, “How do I learn how to do that? How do I get in that box?”

Eventually, he did. The title We Had a Little Real Estate Problem refers to Hill’s signature joke, which he told in his first appearance, in 1978, on The Tonight Show (by then hosted by Carson): “My people are from Wisconsin. We used to be from New York. We had a little real estate problem.” It’s both a joke and a fact. The Oneida were one of the tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy, in what’s now upstate New York. They fought on the side of the colonists in the Revolutionary War, but many Oneida were pushed off their land anyway. They moved west and reestablished themselves near Green Bay. There are now Oneida reservations in both New York and Wisconsin. The line about real estate compresses centuries of history and injustice into seven laconic and eloquent words. Like “Take my wife—please,” it goes for maximum density. Hill compressed the sentiment further in a “Henny Youngblood” homage, “Take my land—please!”

All of Hill’s routines derived from his being Indian, and his subjects ranged from the origin of the name “Indian” (“Sure glad [Columbus] wasn’t looking for Turkey”) to the Pilgrims (“Pilgrims came to this land four hundred years ago as illegal aliens. We used to call them whitebacks”) to the Battle of the Little Bighorn (a complicated, rather broad joke involving General Custer, a cow with a halo over its head, and the punch line “Holy cow—look at all those motherfucking Indians!”)

On his way up, Hill played some tough gigs. He once did his act in San Francisco at the People’s Temple, run by the cult leader Jim Jones (“Jim Jones thought I was funny”). Other venues—powwows, Native rec centers, land-rights rallies where he opened for the singer Buffy Sainte-Marie—were more far-flung. Native American comedians sometimes perform a long way from anywhere, in places where even microphones and chairs are not a given, or where somebody’s back porch is the stage and the microphone is a bullhorn. Vincent Craig, a Navajo comedian, sometimes performed on the back of a flatbed truck in open fields. The Ladies of Native Comedy, a three-woman troupe, have worked on bare ground in the middle of the desert while trying to stay in the headlights of a car. Many indoor venues—such as a motel in Elko, Nevada, or a steakhouse near Mount Rushmore, or the Fiesta Room in the basement of the Phil-Town Truck Stop in Sturgis, South Dakota—sound not much more promising.

Remoteness, a difficult fact in the lives of many Native people, makes it hard for the comedians among them to get performing time. Nesteroff follows Jonny Roberts, an Ojibwe social worker raising a big family on a reservation in northern Minnesota, who drives five hours to the Twin Cities to do seven minutes of stand-up and then drives five hours back, arriving in time to help his wife get the kids to school in the morning before he goes to his day job. When at the end of the book he quits the job so he can devote himself to comedy full-time, you wonder how that will work out. As one might guess, beginner stand-ups usually make no money.

Nesteroff’s previous book, The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels and the History of American Comedy, provides a wild ride through that larger subject. Not a single Native American comedian or humorist appears in it: there’s no mention of Hill, and in the part about vaudeville Rogers does not turn up, either. Within comedy, there are worlds that don’t overlap. Nesteroff, who grew up in western Canada, had been used to seeing Native issues in the news all the time, and Native stand-up comedians on TV. When he moved to Hollywood ten years ago, he was surprised at how few Native performers he saw in the entertainment business. He knew that plenty of Native people were doing stand-up, and he wrote We Had a Little Real Estate Problem to remedy the omission.

Mainstream comedy has always been mostly white, and tilted Jewish, with a smaller but highly influential number of Black comedians (Red Foxx, Cosby, Pryor). Within those categories there have been non-mainstream subsets, such as Black performers who worked mostly at Black nightclubs (the chitlin’ circuit), borscht belt comedians who never left the Catskills, and truck-stop comedians who concentrated on the white blue-collar audience. From the grassroots level a few rose to wider fame; Foxx began as a chitlin’ circuit comedian. Native comedians have their own non-mainstream world, which made Hill’s successes on national TV all the more remarkable and inspiring to them.

A strain that runs between both books is the diciness of comedy as a way to make a living, or even as a way to live. Some of the most successful comedians go through unusually drastic career swerves. One might have thought, from watching Shecky Greene’s talk show appearances years ago, that he was a semi-funny hack-ish comedian more admired by the hosts, who seemed to be friends of his, than by the audience. In The Comedians Greene careens through the story as a comic genius–madman, climbing the curtains in Las Vegas nightclubs and driving his Cadillac into the fountain of the Caesars Palace Hotel. Frank Sinatra has him beaten up (but for something else). Then there’s Rodney Dangerfield failing at comedy, going broke, becoming a scam aluminum-siding salesman, getting arrested, receiving the lucky break of no jail time, returning to comedy with the line “I don’t get no respect,” and making his fortune.

There’s also the slow-motion train wreck of Lenny Bruce as he descends toward heroin addiction and poverty while performing some of the most avant comedy ever, admitting, for example, not only that the Jews killed Christ, but that “we did it—my family. I found a note in the basement. It said, ‘We killed Him. Signed, Morty.’” (The joke as I remember it; it’s not mentioned by Nesteroff.) There’s the Greek-dialect comedian Parkyakarkus, also known as Harry Einstein, delivering a hilarious monologue at the Friars Club, sitting down to a roar of applause, and dropping dead of a heart attack. But there’s also the calming presence of his sons, Bob Einstein and Albert Brooks, whose own careers in comedy seem to have been less fraught.

Nesteroff considers the special difficulties faced by comedians whose subject is politics. When Oswald shot Kennedy, he also as good as destroyed Vaughn Meader, the Kennedy impersonator whose first comedy album, The First Family, went platinum in 1962. Meader’s career ended with the assassination the following year. He began drinking, ran out of money, scrounged in garbage cans. Mort Sahl, whose act involved reading and commenting on that day’s newspaper, lost popularity by clinging to political riffs when the fashion changed. Bob Hope suffered from a similar problem, constantly teeing off on hippies and the counterculture and boring everybody but his own Palm Springs demographic.

A figure of importance in both The Comedians and We Had a Little Real Estate Problem is Dick Gregory, the Black comedian who not only found most of his subject matter in politics but who joined marches for civil rights and was beaten and arrested and jailed. Charlie Hill took inspiration from Gregory, who was his hero. The two both came up in the late-Sixties, early-Seventies protest era, and Gregory even participated in Native fundraisers and land rights demonstrations. Public awareness of Native issues in those years would later shrink to a point where some people remembered only the American Indian Movement (AIM) from the takeover of Alcatraz Island, and maybe a larger number could also recall Marlon Brando turning down the Academy Award to protest Hollywood’s mistreatment of Indians. Hill’s career as a comedian began in that political atmosphere. In the first comedy routine he did on network television, he said that his dream was to win an Academy Award and turn it down in protest of the mistreatment of Marlon Brando.

Yet Nesteroff doesn’t give some of the political moments the deeper look they deserve. He talks about the case of Leonard Peltier, which is an opaque business to this day, but he mentions only in passing the killing of two FBI agents in 1975 that led to Peltier’s arrest, trial, and conviction. Jack Coler and Ronald Williams had come to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota during an investigation of crimes there, and they were brutally executed at close range after first being ambushed and wounded. And it’s weird to see the name of Anna Mae Aquash listed without further identification among the important women behind the scenes at AIM. Aquash, a Mi’kmaq tribal member from Nova Scotia, was thought by AIM higher-ups to be an FBI informant, and they may have ordered her murder, in 1975; two men were given life sentences for the crime. In a book about comedy, it might have been hard to put that in, but some reference should be there, for her sake and for the sake of reality.

Hill’s career did not last long enough. During the 1980s boom in stand-up that strewed at least 260 comedy clubs across the country and multiplied opportunities for comedians on TV, Hill worked a lot. But in the early 1990s the boom ended, TV appearances dried up, and he was broke. He found occasional writing jobs, such as for the sitcom Roseanne. Meanwhile Native would-be comedians were watching his old cassettes and memorizing his groundbreaking routines. Today, young Native people still know and revere his name. A Canadian Ojibwe, Craig Lauzon, said Hill was “the first genuinely First Nations person I ever saw on TV, and he wasn’t pretending to be anything else.” Working only seldom and unable to afford his apartment in Venice Beach, Hill went back to the family home on the reservation in Wisconsin with his Navajo wife, Lenora Hatathlie. There he was diagnosed with lymphoma, and he died in 2013 at the age of sixty-two.

In the most recent decade, political events again brought attention to Native comedy. The pipeline protest on the Standing Rock Reservation in North and South Dakota drew tribal delegations from around the continent; as the protests grew, attracted more coverage, and (temporarily) succeeded, Native comedians and performers found they were getting more calls and opportunities for work. The 1491s, a comedy troupe of five Native writer-performers, had existed before the protest, doing shows at reservations and small-to-medium venues. After Standing Rock, they branched out abundantly. Troupe member Thomas Ryan RedCorn took a writing job on Rutherford Falls, a cable sitcom with a large Native cast, whose showrunner is Sierra Teller Ornelas, the sixth-generation Navajo weaver.

Another of the 1491s, Sterlin Harjo, a Seminole independent filmmaker, co-created a series for FX called Reservation Dogs, based on life in his hometown in Oklahoma. Everyone who writes for the show is Native, plus most of the cast. This multi-episode documentary-style comedy-drama is brilliant and hilarious—the best modern American Western I’ve seen. Among its many standouts, Dallas Goldtooth, also of the 1491s, portrays the ghost of a Lakota warrior who has returned from the spirit world to cajole and counsel one of the characters and offer fractured wisdom; he makes me laugh to tears. The show’s details of res life are sharp—the rearview mirror duct-taped to the windshield, the lariat lying coiled-up and forgotten on the floor next to the mops by the restroom in the town’s convenience store. I don’t know if the lariat was intended to refer to Will Rogers, but in that setting how could it not? The show certainly has an awareness of history; one of the minor characters is named Fixico.

Your standard B-movie cowboy had only about four lines: “Yep,” “Nope,” “Thank you kindly, ma’am,” and “I wouldn’t do that if I was you, mister.” Just four lines, and some dust and six-shooters, and that’s your whole story. But if the standard cowboy had little to say, the stock Indian had less. In the non-Native imagination, Indians were supposed to be stoic and silent. Where this fantasy came from is a mystery, because in actual meetings between whites and Native people of the Americas, the Natives often said plenty. In an account of the Spanish conquest of Cuba, Bartolomé de Las Casas writes of a Franciscan friar who tried to baptize a Native by promising him that baptism would get him into heaven in the next life. The Native asked if he would meet other people like the friar in heaven; the friar said yes. The Native replied that in that case he preferred not to go.

When Joseph Brant, the Iroquois leader who translated the Book of Mark into Mohawk, met King George III, he was told that he had to kneel and kiss the king’s ring. Brant declined but offered to kiss the hand of the queen instead. Sometimes the indigenous people observed even fewer proprieties. During the Battle of Boston, in 1775, the Americans’ Mohican allies were described as standing on the shore and mooning the British navy.

Impassive, with an austere dignity of mien—such was supposed to be the deportment of the Noble Savage. None of that fit with the image of a person mooning a warship or laughing his head off. When the historian Francis Parkman lived with a tribe of Oglala Sioux in 1846, their humor flummoxed him so that he shrank from describing it. In his book The Oregon Trail, the greatest warrior of the tribe wins Parkman’s admiration, with passages referring to “his statue-like form, limbed like an Apollo of bronze,” his “singularly deep and strong” voice, and so on. Then suddenly something strikes the bronze Apollo as funny, and Parkman says, “See him as he lies there in the sun before our tent, kicking his heels in the air and cracking jokes with his brother. Does he look like a hero?”

Parkman can barely endure the sight. After those two sentences, he’s back to describing the warrior majestically arrayed and riding off to battle. He doesn’t understand that he has just glimpsed a whole continent laughing. And what does “before our tent” suggest? Was it possible that the Oglala hero and his brother were laughing at…him?

The famous portrait photographs of Native Americans taken by Edward Curtis in the early 1900s were intended to preserve a record of this people before they died out. Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote the foreword to an edition of Curtis’s book The North American Indian, said that soon the Indian would disappear and join his vanished ancestors. The subtext suggested that this development would be all for the best, merely part of the march of progress, and that nobody, not even the already-silent Native people themselves, need feel too badly about it. The racism of the whole notion paralleled the reduction of Black people to racist caricatures in public imagery at about the same time. The mute and vanishing Indian helped excuse land theft and treaty-breaking and neglect, as the anti-Black images spuriously justified Jim Crow. But human beings, when not totally exterminated, tend to survive—and survive as themselves, triumphantly. In 1900 about 237,000 Native Americans remained in the present-day United States. According to the 2020 US census, 9.7 million people now identify themselves as Native Americans.

Humans are resilient, and the risky exhilaration of making one another laugh helps them to be. Again and again in We Had a Little Real Estate Problem, Native people describe how comedy sustained them, and how seeing comedians who looked like themselves lifted them and changed their lives. Nesteroff writes about a few comedians who worked partly in Yiddish and some who work partly in Navajo. Chances are that members of such small categories will never reach the mainstream. I like to think of the Navajo Vincent Craig, whom most people never heard of, performing stand-up for sold-out audiences of two thousand in the remote Four Corners region of New Mexico. Or the 1491s finding inspiration in Charlie Hill and Mel Brooks, making kids on reservations laugh; and if a wider audience likes the group’s work, that’s great, too. As Bobby Wilson, another of the 1491s, says, “I’m not saying we’re saving the world or anything like that, but it’s just a solid contribution.”