Empty Wardrobes is an appropriate if brutally reductive title for this unsparing depiction of the lives of women in mid-twentieth-century Lisbon, executed by the Portuguese writer Maria Judite de Carvalho (1921–1998) as precisely and without sentiment as an autopsy. Originally published in 1966, it is the first work by Carvalho to appear in English, in what seems an excellent translation by Margaret Jull Costa. Deftly and cunningly written, narrated by an observer who glides in and out of the text with the patrician disdain of a Nabokov character, Empty Wardrobes is gradually revealed to be a double portrait: at its core are two middle-aged Portuguese women—two “empty wardrobes”—ironically linked by their relationship to a preening cad who treats both of them badly and walks away blithely untouched by either.

Though in her impassioned introduction Kate Zambreno describes Empty Wardrobes as “a hilarious and devastating novel of a traditional Catholic widow’s consciousness,” there is not much that is even mildly amusing in Carvalho’s steely, unadorned prose; certainly there is little Catholic consciousness in the incurious Dora Rosário and virtually nothing of the familiar domestic impedimenta of Catholicism. Dora doesn’t observe the sacraments, even confession and communion; we never see her attending mass; if she is concerned with the condition of her soul, we are not made aware of it; her “religion” is the observation of unvarying routine performed with “eyes…as dull as an empty house or unnaturally bright when she became excited.”

Zambreno also describes the novel, for all its domestic interiority and apparent indifference to history, as a “deeply political” work of fiction reflecting “the ambient cruelty of patriarchy, an oppression even more severe in the God, Fatherland, and Family authoritarianism of the Salazar regime [1932–1968] in Portugal.” Indeed, a stifling sort of ether wafts from the cramped interiors of Empty Wardrobes: Dora is first the manager of an antiques shop with few customers, then a saleswoman in a cheap furniture store selling “basic pinewood furniture, mattresses, sofas.” Yet it’s difficult to see how her congenital dullness can be attributed to the reign of a patriarchal dictator, for surely an adult so lacking in autonomy is a special case; her daughter, who is determined to live a very different sort of life, tells her, “You married a man who was poor and lazy…. I’m going to marry a rich, energetic man who loves me.”

Maddeningly naive, passive, and unquestioning in her continued devotion to the deceased husband who left her penniless and with a child to raise, Dora is, at thirty-six, already “ageless and hopeless,” in her daughter’s words. She is dissected by Manuela, the cold-eyed and unsentimental narrator, as if she were a laboratory specimen:

She was always a woman of few words. She never said more than was strictly necessary—the bare indispensable minimum…. She would sit quite still then, her face a blank, like someone poised on the edge of an ellipsis or standing hesitantly at the sea’s edge in winter, and at such moments, all the light would go out of her eyes as if absorbed by a piece of blotting paper; for all I know, she may still be like that, because I never saw her again.

And later:

She had neat, regular features, but had never done anything to help nature. Never. She seemed, rather, to be unconsciously intent on hampering it. You could describe her face as lackluster: matte skin, pale lips, dull, straight brown hair tied back…. She took so little trouble over how she dressed that even her body went unnoticed.

Not sympathy but a detached sort of cruelty characterizes Manuela’s interest in Dora, which invariably turns upon Dora’s flaws and her defeated prospects; canny, icily detached, and near-omniscient, Manuela’s perspective seems identical with the author’s, for we never see Dora behaving in a way that refutes Manuela’s judgment.

Indeed, the narrative “I” in Empty Wardrobes is paradoxical: as a voyeur in Dora’s life Manuela is both nowhere and everywhere, only briefly in Dora’s presence and the rest of the time imagining scenes that (presumably) take place beyond her scrutiny. Disarmingly Manuela says of herself:

I’m not part of this story—if you can call it that—I’m a mere bit-part player of the kind that has not even a generic name, and never will have, not even in any subsequent stories, because we simply lack all dramatic vocation.

She calls herself, not apologetically but with a kind of pride, a “sterile woman”—a woman who hasn’t wanted children.

In a more conventional novel, certainly in one exploring feminist bonds of sisterhood within a stultifying patriarchal culture, as in the fiction of Elena Ferrante, we would likely see Manuela, abandoned by her longtime lover for a younger woman, joining forces with Dora; and each woman, victimized by men, would become stronger as a consequence. But Carvalho is not interested in feminist romance, any more than she is interested in traditional romance: rivals within the patriarchy, women have no instinctive sisterly feelings for one another and remain hostile and estranged. Manuela thinks, with characteristic disdain, “I thought that perhaps what [Dora] needed was a good shake or, better still, an X-ray, so we could see if she did actually have more inside her than just lungs and a digestive system.”

Advertisement

In her premature but life-defining widowhood, Dora is a Portuguese equivalent of those pathetic persons “outcast from life’s feast,” in James Joyce’s poignant phrase. She is emotionally and sexually bereft; her “threadbare coat, with runs in her stockings, [and] untidy hair” unsex her as mercilessly as her need for money deprives her widowhood of romantic nostalgia. Dora reminds us of those lonely, left-behind Dubliners inhabiting the penumbra of Joyce’s richly peopled Irish world, involuntarily celibate casualties of a repressive Roman Catholicism that provided no meaningful occupation for unmarried women apart from the convent.

We may also think of Brian Moore’s most “painful case”: the luckless heroine of Judith Hearne, for whom virginity has become a kind of curse and episodes of drunken forgetfulness her only solace. With a kindred subtlety and sympathy Colm Tóibín has written of more contemporary Irish outcasts from life’s feast, notably the widowed Nora of Nora Webster in her similarly claustrophobic, tight-knit, and conscribed small-town Irish world; and there are the achingly lonely unmarried Englishwomen in the novels of Anita Brookner, wraithlike figures scarcely distinguishable from one another in their yearning for a love that might provide them with some measure of self-definition in a man’s world.

Such figures of female pathos are virtually the only inhabitants of Carvalho’s Lisbon, as sparely presented as a landscape by de Chirico, but they lack the inner lyricism of Tóibín’s and Brookner’s women. They certainly lack the ferocious resentments and strategies of self-determination found in the female characters of Carvalho’s contemporary Doris Lessing. Apart from Dora there are two other widows—empty wardrobes—as well as Manuela; these are women whom life has also left behind, without men and without meaningful employment or interests. “When single women reach a certain age, they’re so…frightening. They wither away, don’t they?” Dora’s daughter, Lisa, asks tactlessly. Dora’s mother-in-law, Ana, at least has money, which gives her empty life a measure of freedom. Dora’s Aunt Júlia, another widow—“a small, serene, pleasant woman, slightly stooped…. A hieroglyph that was more like a meaningless doodle”—takes refuge in hallucinatory memories and silly dreams of flying saucers, which Dora professes to envy: “At least she believes in something.” (Aunt Júlia is characterized as an elderly, senile woman, so it’s something of a shock when we learn that she is only in her late forties!) And Lisa, advantaged by a heedless youth and beauty, impetuously marries the very man, more than twenty years her senior, who has ruined what remained of her mother’s atrophied life.

Few scenes in Empty Wardrobes are dramatized, as if Manuela, recalling the banality of her subject, can scarcely be troubled to evoke them. She resorts instead to desultory summaries: “And so it was. [Dora] got the job, bought the books, and she did learn, earning enough money over the subsequent years to send her daughter to a school for rich kids.” Mired in a mourning for her husband that seems a consequence more of an inadequacy of imagination than of genuine feeling for him, Dora is incapable of initiating change in her life: things are done for her, and to her. A kindly friend arranges for her to have the undemanding but (improbably) well-paying job in the antiques store, which spares her the ignominy of having to beg for favors and money from her late husband’s friends. In this position she drifts like a sleepwalker, in an unvarying routine; no time seems to pass in her stultified life except for her daughter growing out of childhood and into an independent adolescence.

After a decade of widowhood Dora’s sole expression of autonomy is to have her hair styled and to purchase some new clothes, provoking a male acquaintance to inquire, “What the hell has happened to her?” As in Tóibín’s Nora Webster, a still-youthful widow seems to be about to reenter the world after a prolonged emotional stasis, surprising everyone who knows her; but Carvalho has another, more humiliating fate in mind for Dora.

Advertisement

Empty Wardrobes is a short novel that seems longer than it is, for it moves with glacial slowness, as if in the grip of inertia. Years pass in Dora’s life in the space of a paragraph, yet she remains unchanged, a cipher. New clothes, a new hairstyle, will not infuse life into so shallow an individual. Cynically Manuela observes:

In the olden days, some women would shut themselves away in their houses for good when their husbands died. Some didn’t even let the sun in, perhaps because they would find its cheerful face too shocking. Dora Rosário went to work…but when she returned home at the end of the day, it was as if she had never left.

Dora’s deceased husband, Duarte, whom she had absurdly idolized, had prided himself on his very lack of ambition:

I’m not the kind of man who wants to rise in the world at the expense of others, or indeed of myself. That smacks too much of wheeling and dealing…. Nor am I going to stand up in the marketplace listing my many qualities and putting a price on them. I just let myself drift, that’s all I can do and all I want to do.

Here at least is the very antithesis of machismo, one thinks, until it becomes clear that swaggering male vanity can take many forms.

There is no spiritual or religious quality to Duarte’s indifference to the marketplace; he isn’t an ascetic who has repudiated a materialistic life, only the coddled son of a well-to-do mother who has indulged and enabled his narcissism. Dora understands this but lacks the courage to object: “Had she said anything…it would have spoiled everything”—that is, the folie à deux of a marriage in which the husband is placed on a pedestal for the wife to admire regardless of his flaws. Though it’s stated repeatedly that Dora loves Duarte very much, we see little evidence of any physical or emotional attraction between them; Duarte seems as lackluster and sexless as Dora, an underimagined character in an underimagined narrative. When he becomes ill he is dispatched within a paragraph, leaving Dora stunned:

When Duarte died, and Dora realized that he was lost forever, it was as if the earth around her shook, and only the tiny scrap of earth beneath her feet remained still. Her world, already sparsely and rather poorly populated, was suddenly deserted.

Dora wants her grief to remain “uncontaminated,” but with only a small pension from Duarte’s employer to support herself and her daughter, “thus began her calvary, her daily round”—searching newspaper ads for jobs, begging for small sums of money from everyone she knows, who soon come to resent her even as they pity her.

This collision of the widow’s private grief with the public fact of her diminished financial state, as a catalyst for Dora’s quasi awakening, comes as a welcome development in the novel. It is bluntly completed by her mother-in-law’s decision to apply a “fixation abscess” to her: “You need such an abscess, and I’m the cruel doctor who’s going to create it and make you suffer.” In the novel’s most dramatic scene, Ana tells Dora that Duarte had been thinking of leaving her before he became ill, to live with another woman:

A work colleague of his, I think, although I can’t remember her name anymore. He’d made up his mind. For once in his life, he was going to take the initiative, a real novelty…. I didn’t try to dissuade him. I thought perhaps that other woman might make something of him. But then he fell ill…. She was a small, nervous woman, like a very intelligent mouse.

Following this revelation, which comes a decade after her husband’s death, Dora is catapulted into an altered consciousness that inspires Carvalho to her most precise and poetic language, suggesting the novel’s latent possibilities, largely unexplored:

She wanted to sleep, to escape herself, to escape the new life she would now be obliged to live, but the paths into sleep were more difficult, more complicated than ever. Cul-de-sacs, long rivers with no tributaries and no sea, no sources either, rocky mountains that she would have to scale in order to see over to the other side, to another landscape.

Is Dora really courageous enough to venture into this foreign landscape? Can she transform the deep hurt of her husband’s infidelity into a repudiation of him, and of her prescribed role as his widow? Carvalho leads the reader to expect liberation when, in an ironic reversal, Dora’s trust in a male acquaintance, Ernesto, by chance the longtime lover of Manuela, leads to a near-fatal car crash that leaves Ernesto, the driver, untouched but Dora physically disfigured, with a scar that runs “diagonally from her forehead to halfway down her cheek.” Her humiliation is complete.

Empty Wardrobes is a bleak, embittered novel holding little possibility of happiness except through delusion; not even a sisterhood of outcasts is possible for the women scorned by men. Manuela observes with chilling detachment as Dora falters in her attempt to establish a rapport with her:

[Dora] couldn’t find quite what it was she meant, and I didn’t help her in the search…. It was raining, and she was a gray woman, slightly bent, lost in a plundered city deserted after the plague. I noticed that she walked uncertainly, hesitantly, teetering slightly, as if she were a little drunk or had not quite woken up from a long nap.

Shrewd and coolly distanced from life as she imagines herself, Manuela is nonetheless “absolutely flabbergasted” and “lost for words” when Ernesto informs her bluntly that he is leaving her to marry the seventeen-year-old Lisa.

As Manuela has observed earlier, “The calm waters of an apparently stagnant river can, at a certain point, form a torrent but then, later, continue serenely on their way.” So, too, the trancelike stasis of Empty Wardrobes is interrupted by a flurry of drama—a belated revelation of an infidelity, a devastating car crash—and the finality of despair, which will then subside into the banal and everyday. At the novel’s end one waits in vain for Manuela to at least embrace the scarred Dora in recognition of their common loss; but Manuela, too wounded to give solace to another, stands stiffly apart as Dora leaves her apartment. Pride dooms Manuela to solitude as rain continues to fall, “passively, from an old and ailing sky, bleary-eyed and weary with life. Now that I lived alone, it was a day like so many others. Another number to be subtracted from my account.”

Since relatively little Portuguese fiction is translated and published in the US, Empty Wardrobes is of particular interest to American readers. One might wish for more nuanced characters and a more capacious representation of Portuguese life, which is surely more varied and engaging than suggested here, but there is no doubting the authenticity of Carvalho’s vision and the originality and severity of her voice, as scathing and pitiless in her depiction of “empty” women as in her depiction of oafish swaggering machismo.

This Issue

February 10, 2022

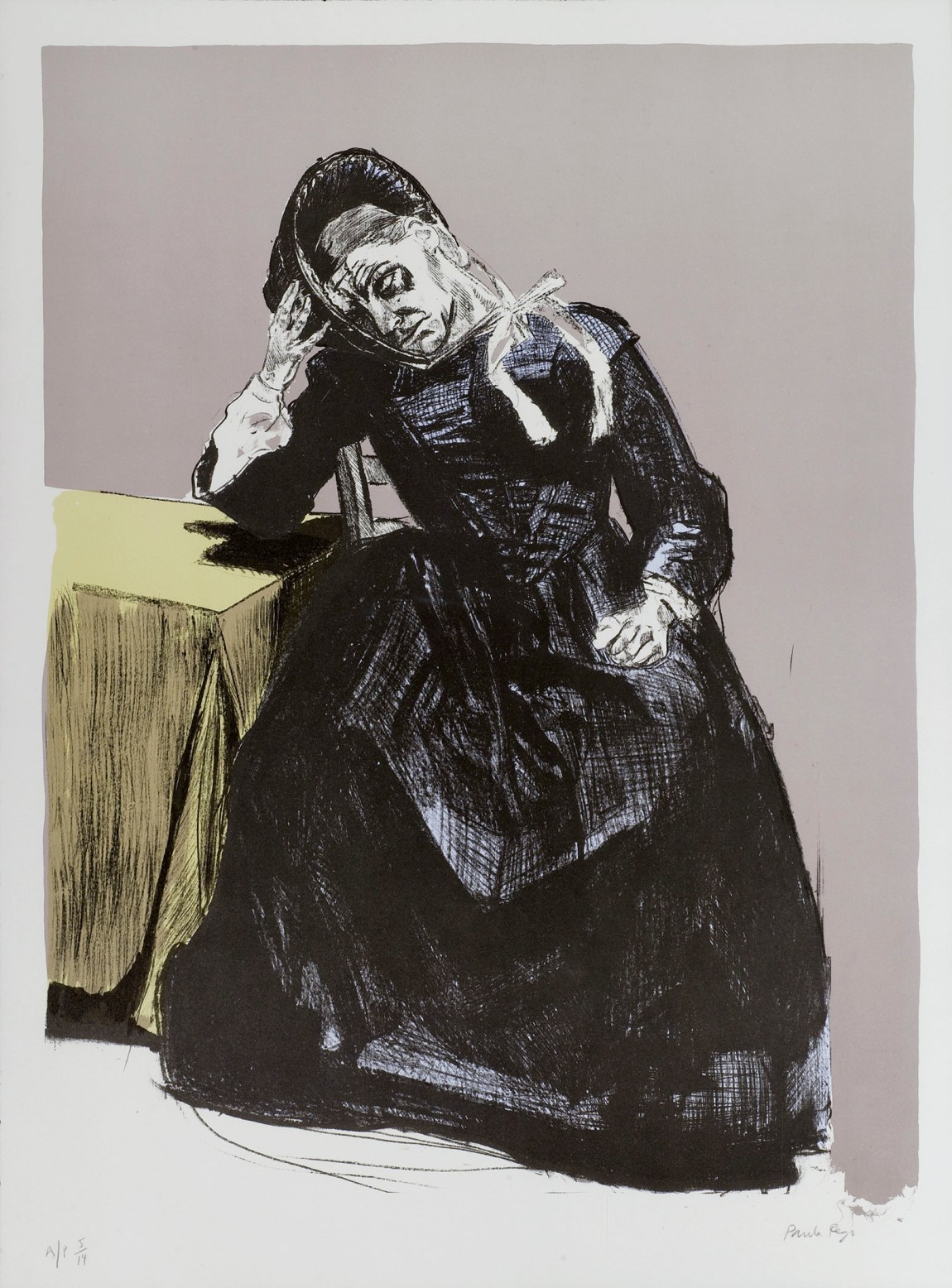

Our Lady of Deadpan

Picasso’s Obsessions

In the Beforemath