In 1793 the French mathematician, intellectual, and moderate revolutionary the Marquis de Condorcet, who had hoped that the Revolution could bring about a peaceful era of equality, justice, and human rights, and who for denouncing the bloodthirsty despotism of Robespierre and the Jacobins had been banished and threatened with death, was in hiding in a house in Paris. He had been taken in by a courageous landlady, Mme Vernet. On the day Condorcet learned that thirty of his moderate colleagues had been guillotined, he broke down and wept, lamenting his outlawed state. Mme Vernet told him that the Jacobins could make him an outlaw, but that “no one could expel him from the human race.”

To be a member of the human race is to undergo loss, anguish, bereavement, betrayal, failure, aloneness, and the fear of death, and Michael Ignatieff’s remarkable and moving new book, On Consolation, written out of the dark times of a world pandemic, tells some dramatic stories of the worst that can happen to human beings and the worst they can do to one another. But to be human is also to look for meaning, joy, and consolation. As Ignatieff noted in his earlier book The Needs of Strangers, where some of these thoughts had a first outing, “We are the only species with needs that exceed our grasp,” needs for “metaphysical consolation and explanation.”

To be human is also, in some cases, to possess extraordinary courage, endurance, intellectual power, imagination, and capacity for hope. Condorcet, an admirable specimen of the human race in spite of the wretched failure of all his hopes and ideals, continued to the end to express a belief in progress and in a future time when

science, industry, and political economy would make plenty available to all. Emancipated by knowledge, human beings would live in freedom and peace; and war, the scourge of civilization, would die away.

Condorcet’s illusory rational utopianism is one of many possible “consolations” under examination here. Ignatieff doesn’t want to prescribe one over another but to understand how consolation has been configured at different times, in different eras of thought, and to suggest what we might learn, or what consolation we might derive, from these examples of “the human experience.”

The consolation business is a crowded market. There are many books out there, presumably of help to many readers, on how to come to terms with suffering and bereavement and how to bear grief, with titles like It’s OK That You’re Not OK and I Wasn’t Ready to Say Goodbye and I’m Grieving as Fast as I Can. Out of the pandemic have come timely aids like This Too Shall Pass and Alone Together: Love, Grief, and Comfort in the Time of COVID-19. There are books on how to understand your emotions, such as David Whyte’s Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words (2015). There are books of intellectual advice, like Alain de Botton’s personal take on “how to become wise through philosophy,” with encouraging thoughts on Epicurus, Montaigne, et al., in The Consolations of Philosophy (2000).

And there are some notable books by writers who have brought the powers of their imagination and language to bear on the experience of bereavement, among them C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed (1961), Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (2005), Julian Barnes’s Levels of Life (2013), and Max Porter’s Grief Is the Thing with Feathers (2016). Readers respond intensely to such books because they often find their own lives reflected in them, but told in ways that they couldn’t have imagined and that provide their own form of consolation.

Ignatieff’s approach to consolation is not quite like any of these. He is dubious about the therapeutic mode that treats suffering “as an illness from which we need to recover” rather than a condition that may deepen our understanding of the meaning of life. Late in the book he quotes the view of the great, implacable Emily Dickinson on what is often called “the healing power of time”:

They say that “Time assuages”—

Time never did assuage—

An actual suffering strengthens

As Sinews do, with age—Time is a Test of Trouble—

But not a Remedy—

If such it prove, it prove too

There was no Malady—

The book starts on a personal note with Ignatieff’s attendance at a choral festival in Utrecht in 2017, where he was giving a talk on “justice and politics” in the Psalms, which were being sung in different musical settings. He was overcome by the emotional effect they had on him, a nonbeliever, and on others like him. How do religious texts and religious music still provide consolation and “tears of recognition” in what he thinks of (though others might disagree) as a largely secular era? The book took shape out of that question, which begged to be asked all the more intensely during the pandemic.

Advertisement

But on the whole he is not autobiographical, though the dismal hospital deaths of his own parents, decades ago, lie behind the book’s affecting final chapter on Cicely Saunders, founder of the palliative care movement. Nor does he tell us where and how we should find solace. His own working life—as a historian of ideas; as the biographer of Isaiah Berlin; as a broadcaster, memoirist, essayist, and novelist; as an unsuccessful Liberal politician in Canada; and as rector, in turbulent times, of Central European University in Hungary—has fed his interest in the intellectual context of ideas of consolation, whether these be Stoic, Hebrew, Catholic, or Protestant, Enlightenment or rationalist, Marxist, liberal, or secular. So the book is historical, proceeding in great jumps from the book of Job to European writers of the twentieth century (and giving sharp and succinct accounts of the collapse of the Roman Empire, or the French Revolution, or the American Civil War).

It is also conceptual, analyzing the main words that are associated with consolation. Consolation can mean faith (though there are plenty of people in this book for whom faith is a false consolation). It can be a demand for divine validation, or a counter to a sense of meaninglessness, or the ability to write a narrative of self-realization. It can be the bearing of witness, or the result of steadfastness, or a commitment to living in truth. Above all it is linked to hope and to solidarity.

But On Consolation is more about individuals than abstract definitions. This is a book of life stories, some more consoling than others. Ignatieff begins with the Old and New Testaments at their most alarming. The appalling story of Job and his God-sent tribulations is described, as hopefully as possible, as “a demand for divine validation,” a refusal of false consolations, and a protest against being condemned to “meaninglessness.” The Psalms, so full of lamentation and anguish at God’s inscrutability, teach us, Ignatieff says, the relationship between despair and hope. Saint Paul, with his traumatic conversion and his relentless mission to turn an obscure sect into a universal faith, a mission fraught with persecution and bitter disappointments, finds consolation, according to Ignatieff, in the love and fellowship of the faithful.

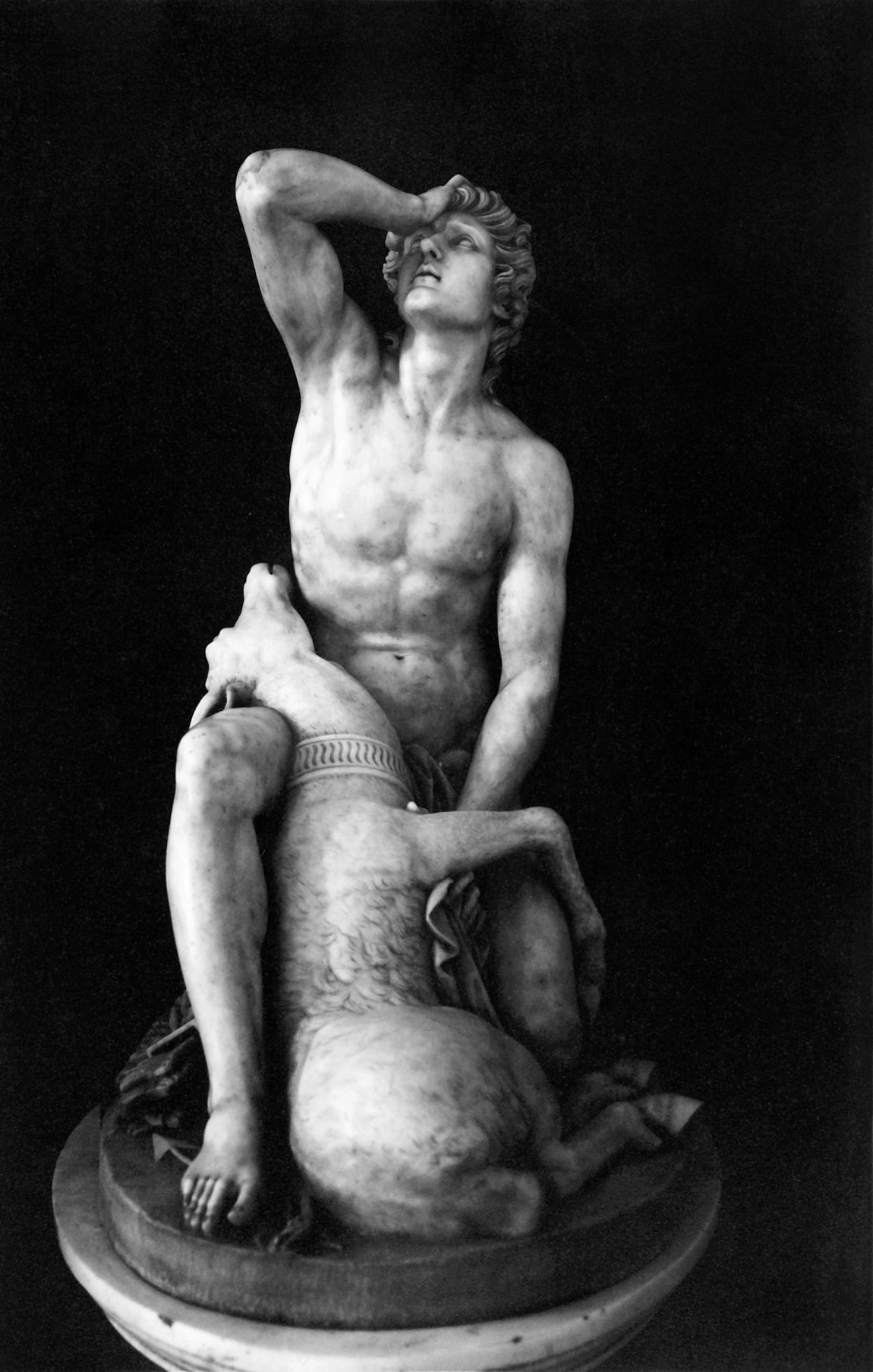

From the Bible we turn to some severe classical examples. Here is Cicero’s masculine code of Stoicism—men mustn’t cry or show weakness—which provided consolation by showing off your capacity for “manly…self-control” for the admiration of your male peers, but which didn’t prevent him from falling into inconsolable depression when his daughter died. Here is Marcus Aurelius writing his confessions in “fear and loneliness” after a life of successfully running an empire and subduing barbarians. Here is Boethius, at the terminal point of that empire’s decay, drawing on Greek, Roman, Hebrew, and Christian traditions from “the memory palace of his erudition,” putting his faith in “philosophical reasoning” while awaiting a horrible death, and finding consolation in “the writing itself.” Ignatieff notes that any consolation these writers provide others comes from their “candor” about

the loneliness, discouragement, fear, and loss that make us seek consolation in the first place. For it is consoling to know that not even an emperor can get through the night, alone with his thoughts. That is something we can share with him.

There’s more pleasure to be had from Montaigne’s humane, worldly enjoyment of the physical experiences of the everyday, his attention to “the demands of ordinary life and the people around us,” and his holding on, in the face of mortality, to the consolations of “diversion” and hedonism, of simply “living and creating.” And Ignatieff admires the philosopher David Hume’s matter-of-fact acceptance of his mortality, which, in the late eighteenth century, ushered in “a new way of dying.”

Hume also figured in The Needs of Strangers as a revolutionary thinker who “waved away the blindfolds of Christian consolation.” Ignatieff doesn’t accept his view that we have no natural need of “metaphysical consolation,” but he respects it. In both books, he tells the story of Hume on his deathbed, joking with Adam Smith about his imminent journey across the River Styx. Hume imagines asking Charon for just a bit more time—to “correct the editions of his works,” or to wait and see “mankind delivered from superstition.” “But he could guess Charon’s answer: ‘That won’t happen these two hundred years. Into the boat this instant, you lazy loitering rogue.’”

Hume’s resolute atheism (which horrified some of his death-fearing friends, like Johnson and Boswell) provides one kind of consolation even while rejecting dependence on it. Though Ignatieff chose not to write about Isaiah Berlin in On Consolation, Hume’s deathbed equanimity echoes Ignatieff’s account of Berlin in old age, briskly dismissing the consolations of philosophy:

Advertisement

As for the meaning of life, I do not believe that it has any. I do not at all ask what it is, but I suspect it has none and this is a source of great comfort to me. We make of it what we can and that is all there is about it.

But the search for the meaning of life is hard for human beings to relinquish, as much in the public as in the private sphere. Ignatieff’s chosen philosophers, revolutionaries, politicians, and thinkers of the modern world—Condorcet, Marx, Lincoln, Max Weber, Camus—construct their testimonies not only out of personal needs but in relation to the condition of the world and their desire for social change. Marx hoped for a new age of freedom and reason emerging from “the revolutionary rise of the proletariat,” while he was able to call only on “stoic endurance” in his own troubles, like his wife’s death from cancer. Lincoln encouraged opposing sides to “join together” and “find some common understanding,” to embark on reconciliation and not vengeance, after the nation’s tragically divisive war. Weber urged the next generation, during and after Germany’s defeat in World War I, to shoulder “the responsibilities of politics.” Camus discovered, through his contacts with the Resistance during the German occupation of France (for which his “plague” became a metaphor), that our only resource is “our reliance upon and our need for each other.” These are all, in their extremely different ways, positions carved painfully out of dark times of conflict and despair.

The book doesn’t eschew tragedy. To show us consolation as something struggled toward, not easily arrived at, it gives us unsparing scenes of grief, death, torture, and cruelty, of which the most shocking, perhaps, is the story told by Camus in 1943 of the German prison chaplain on a train with French prisoners, one of them a teenage boy, going to their execution. The priest consoles the boy (“I will be with you and so will God too”), but when he manages to escape, the priest alerts the guards so they can recapture the boy and take him on to his death. Camus’s rage at such “false consolation” is channeled into The Plague, a book “about resistance in the face of evil.” Ignatieff takes his own strong line about the lessons in resistance we might draw from these examples, for instance from Lincoln’s attempts to “bind up the nation’s wounds”: “He struggled with exactly what we struggle with: the tidal force of political malice that recurrently rises and threatens the hard-won civility on which a democracy depends.”

Ignatieff’s strongest emotions, and some of his most tragic examples, are found in the stories of his twentieth-century European and Russian heroes, Primo Levi, Anna Akhmatova, Miklós Radnóti, Václav Havel, Czesław Miłosz. Their endurance under duress, in Nazi concentration camps or under Stalin, as political prisoners or exiles, is at the heart of the book’s message:

It is not doctrines that console us in the end, but people: their example, their singularity, their courage and steadfastness…people [who] show us what it means to go on, to keep going, despite everything.

This sense of “solidarity,” of a human “chain of meaning” or “fellowship of witness,” tells people—sometimes wordlessly—that “they are not alone,” but part of “a common world of feeling.”

That recognition of the “human chain” (the title of Seamus Heaney’s last and profoundly consolatory book of poems, though not mentioned by Ignatieff) can be brought home by the smallest, most mundane of encounters. Ignatieff uses three nameless women among his examples. Camus, inspired by his illiterate Algerian mother to create the silent, watchful old woman who sits patiently by a ghastly deathbed in The Plague; Havel, moved to a sense of kinship with strangers by seeing, when he was in prison, the banal plight of a hapless TV weather presenter unable to be heard on air and plunged into panic-struck embarrassment; and Cicely Saunders taking the words of a working-class woman about her pain (“all of me is wrong”) as the basis for a holistic program of care for the dying—all are links in that “chain of meaning.”

The chain can connect us through time, as when Levi, in Auschwitz in 1944, recites Ulysses’ lines in Dante’s Inferno (“You were not born to live your life as brutes”), written in the fourteenth century under the influence of Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy, composed eight hundred years before that. For the chain to be forged, people must bear witness, poems and letters and memoirs must be circulated, texts must be preserved and edited and translated.

Ignatieff is eloquent on the crucial importance of these textual survivals, whether he’s writing about the Psalms or about Radnóti. The Jewish Hungarian poet, who had survived months of hard labor in a copper mine in Serbia, was being force-marched across Hungary in the autumn of 1944. Whenever he could, he kept on writing short, laconic poems, which he called his “Picture Postcards,” on bits of cardboard picked up on the road. He was shot in the head and his body thrown into a shallow grave, from which, after the war, his papers were exhumed, kept safe by a local Jewish butcher, handed back to his wife, and published in time for her to see him recognized “as one of the greatest poets of Hungary and Europe.” Ignatieff, in some anguish, suggests that those inspiring and courageous writers are now being betrayed and forgotten, at a time when “what they witnessed and suffered is disbelieved.” We owe it to those heroic figures to remember them, and this book makes a good job of it. “History has no consolation to offer,” he concludes somberly, “but it does leave us with duties.”

It’s a high-minded, even solemn tone. As I read On Consolation, often much moved, I couldn’t help calling to mind some more caustic approaches to the subject. Ignatieff’s thoughtful attempt to understand Saint Paul could be contrasted with Virginia Woolf’s savage excoriation of him in her 1938 essay Three Guineas as a prototype for Nazism (“He was of the virile or dominant type, so familiar at present in Germany, for whose gratification a subject race or sex is essential”). Ignatieff’s account of Job pales beside Anita Brookner’s lacerating commentary:

Job is not only wronged, he is duped….

God chooses to come in the shape of a whirlwind, either because He is enraged by the banality of the dialogue to which presumably He has been listening, or to divert attention from His previous absence…. God demands an unconditional worship, beyond causality, beyond reward, beyond understanding. Job, by this reasoning, is condemned to go uncomforted.

It’s intriguing, too, to set Ignatieff’s book alongside Julian Barnes’s witty, skeptical, forensic explorations of the consolations offered for death in Nothing to Be Frightened Of (2008), in which he follows Flaubert’s grimly unflinching recommendation that “by dint of saying ‘That is so! That is so!’ and of gazing down into the black pit at one’s feet, one remains calm.” Barnes opts, more often than not, for “disconsolation.”

Ignatieff might have chosen other examples. His book is almost entirely in and about the European tradition, apart from the chapter on Lincoln. As he says, “Another book could have been written about what Europeans learned from Asian, African, or Muslim sources of consolation.” It is light on women, though there are some strong historical heroines—like that landlady of Condorcet’s or Marx’s devoted and long-suffering wife, Jenny—in the margins. It’s not especially interested in the consolations of nature. It is aimed at an audience with a wide range of cultural references and an interest in the history of ideas. And it concentrates on writers, though there’s a fine chapter on El Greco’s 1580s painting The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, which speaks to the thousands of people who come to see it every year of “the human longing to escape, to be taken up into heaven, and to enjoy the blessing of timelessness.”

There is also one chapter on music. Writing about music and consolation is a risky business, as there is such a vast literature on the way music affects our emotions, and we all know that one person’s musical consolation is another person’s anathema. But music does provide Ignatieff with the best example of how works created in a religious context can still have their effect on a secular audience by reminding them of traditions of thought that “situate individual suffering within a wider frame,” and by providing them with “great languages of consolation” that can “hold out a promise of hope that makes our unbelief somehow irrelevant” and help us to feel, in our grief, “that we are not marooned in the present.”

It allows him to write, too, about those forms of consolation that take us into silence and aloneness. Ignatieff chooses Mahler as his example because of Mahler’s conviction (like Wagner’s) that “music should attempt nothing less than to provide meaning for men and women living after the death of the gods.” He gives a tender account of the Kindertotenlieder, Mahler’s song cycle on the death of children that so tragically anticipated the death of his own daughter. And he uses Mahler to go beyond the idea of the human chain to the more difficult idea of our ultimate solitariness. Ignatieff is much consoled by solidarity, but he also recognizes the inevitable necessity of aloneness. I’m reminded of the verse in Edward Thomas’s “Lights Out” (1917), one of my own “consolation” poems:

There is not any book

Or face of dearest look

That I would not turn from now

To go into the unknown

I must enter, and leave, alone,

I know not how.

Ignatieff describes how at the endings of Kindertotenlieder and Das Lied von der Erde, Mahler takes us into the space beyond notes and words, where we’re each of us alone, as we will be in our dying: “Mahler brings the listener and the music to the very edge of silence, as if to mark the place where music’s consoling work has to end, and the listener must go on to find meaning on his own.”

This Issue

February 10, 2022

Our Lady of Deadpan

Picasso’s Obsessions

In the Beforemath