I began reading Heimito von Doderer’s The Strudlhof Steps at the start of the Omicron surge, when the threat of another winter lockdown made it seem like the perfect moment for a dense and demanding 850-page Austrian novel. This hugely original book requires intense concentration to follow its switchback plot turns, to navigate its confusing leaps in time, to untangle its page-long metaphors, but most of all to keep track of its enormous cast of characters. A classic of German-language literature, first published in 1951, it is only now appearing in English, in Vincent Kling’s deft translation.

Set in 1908–1911 and 1923–1925, The Strudlhof Steps introduces us to a Viennese circle of bright young and not-so-bright-or-young things: ingénues, soldiers, students, musicians, petty crooks, all entwined by decades of flirtations and romances, deep philosophical friendships and family connections, infidelities and breakups. We know what these bankers, lawyers, writers, bureaucrats, and civil servants do for a living, but we rarely see them at work. They’re too busy enjoying the fast life, at cafés and parties, in sports cars, on country walks, at tennis games and in bedrooms. They drape themselves around the louche apartment of Captain Eulenfeld, an alcoholic Prussian aristocrat, former cavalry officer, and cigarette smuggler whose contaminating influence is so widespread that a character describes him as “a kind of disease.” Everyone is seducing everyone else, or already has, or is plotting a future seduction.

The book offers all the rewards of nineteenth-century fiction: we know what these people wear, how they decorate their homes, what kind of cigarettes they smoke. We can measure the distance between their social personae and their authentic selves. Lengthy set pieces transport us to a bear hunt in Bosnia, a rock-climbing expedition, a diplomatic mission to Constantinople, married life in Buenos Aires, a drunken dance party at a country hotel where a love affair of many years comes to a humiliating end. Doderer’s Vienna is as lovingly mapped as Balzac’s Paris, Joyce’s Dublin, Dickens’s London.

But the more traditional elements are scrambled by his modernist disregard for the conventions of chronology, introduction, and explanation, his lack of interest in the helpful signposts and directions that orient readers in time and space. (Where did we meet that character before? When is this party happening?) As in Proust, people vanish and reappear in different guises, hundreds of pages later, or exit the novel, unmentioned, never to return.

Only slowly do we learn to distinguish the principal actors from the walk-ons, and that only after we’ve sorted out their vaguely similar names: Grauermann, Geyrenhoff, and Grabmayr; Editha Pastré, later Editha Schlinger; Etelka Stangeler, later Frau Etelka Grauermann. We meet a lot of characters in a very short span. And yet the novel’s daring wit and its swift, assured transitions between metaphysics and gossip kept me reading contentedly through the 150 or so pages that it took me to get my bearings. The book begins:

When Mary K.’s husband, a man named Oscar, was still alive and she was still walking around on both her beautiful legs—the right one was severed above the knee on September 21, 1925, not far from her apartment, when a streetcar ran over it—a certain Dr. Negria turned up, a young Romanian physician undergoing further training at the well-known medical school here, as a resident at the Vienna General Hospital.

It’s a nervy opening sentence, like one of Kafka’s or Kleist’s, but its true bravado will reveal itself only much later. Streetcars rumble ominously through the background, but if you’re waiting for Mary’s accident, you’ll need to be patient for another 770 pages.

Many things happen in between, yet Mary’s misfortune never completely leaves our minds. On that fateful September 21, 1925, each of Mary’s everyday actions—getting dressed, inviting her friend for tea—fills us with dread. Hundreds and hundreds of pages in, we’re braced for catastrophe to befall a woman who, by now, is only one of the many female characters we have come to know.

At the start we might assume that Mary—appearing so early and suffering so tragically—will be the novel’s heroine. But though she figures in Doderer’s later two-volume novel The Demons (1956), she’s not quite central here. She plays tennis, studies piano, is happily married to Oscar, whose death “of some kind of cancer” gets a sentence or two. She has two redheaded children; she worries about a friend’s marriage and a neighbor’s troubled engagement.

One thing we do learn about Mary is that she was once involved with a certain Lieutenant Melzer, whom she remembers as “pretty stupid.” Mary’s version of how the affair ended is that Melzer left her to rejoin the military and go bear hunting in Bosnia:

Advertisement

Lieutenant Melzer’s eventually decamping—taking his stupidity along with him—had, in a manner of speaking, canceled out that stupidity and with it her own superiority…. He hadn’t a care in the world. She would have deceived him later on…. Because of his being so even-tempered.

The reader may be surprised when Melzer, so unflatteringly remembered, emerges as one of the novel’s most important characters. We are often asked to consider, as Mary does, the question of his stupidity. If he is so stupid, why does he respond so eloquently to beauty? Why does he find it so important to think like a civilian and not a soldier? Meanwhile, Doderer is slyly setting us up for Melzer to do the smartest thing that anyone does in the book. Melzer “never had a ghost of a thought,” he writes.

As far as we know, the first time he ever thought anything at all came on one particular occasion, and then only at a very crucial time and very far advanced phase in his life—we will find out more about it later. Once he finally did it, he did it all the way; he didn’t waste his powder with little displays of agility and ability.

In between the novel’s two time periods, World War I has been fought, the Habsburg Empire has crumbled. Melzer has watched his close friend and mentor, Major Laska, bleed to death in his arms. René Stangeler, another of his friends, was a prisoner in Siberia. But when the novel resumes, no one talks much about the war, the collapsed empire, or the political and economic stresses undermining Austria’s stability. It is 1925, yet everyone’s still partying like it’s 1911. They take the temperature of old passions, recall past alliances, epiphanies, and betrayals. They’re more concerned with a long-ago public scandal that erupted on the Strudlhof Steps (an incident involving a couple who had been caught embracing in the bathroom at a garden party) than with, say, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The steps that give the novel its name are one of Vienna’s art nouveau treasures, a monumental outdoor staircase built in 1910. This landmark is a powerful presence throughout the book and in the lives of the characters who ascend or descend it, admire its grace, meditate on its significance, and imagine how it will look after the end of civilization. The curving and converging flights of steps also suggest the book’s many braided or helical plot twists, its mirroring and doublings. The landings and terraces evoke the rare moments when the characters meet and pause, as if to catch their breath, before setting out in opposite directions that will eventually bring them together again. Melzer is the one who rhapsodizes most eloquently about this “feat of engineering”:

It mounted up, or rather it reached down, placing into orderly arrangement the steep drop-off, truncated and abrupt by nature, of the terrain here, dividing the tight-lipped, nearly barren, all-too-pat statement the terrain made into an abundance of graceful turnings, which the eye could no longer just dart downward in a fast swoop to follow but instead had to lower its gaze as gently as a falling autumn leaf swaying softly through the air.

Perhaps one reason the novel requires such focus is that its characters are so distracted, which makes the narrative often seem propelled by their fits and starts of attention. Dr. Negria, a pediatrician, activist, and lothario, hopes to seduce Mary K., whose marital fidelity he finds pretentious and annoying. She finally agrees to meet him at a café, but en route she is distracted by a tennis game. She stands the doctor up, but it hardly matters, because he has already been distracted himself by a pretty woman at another table. He leaves the café with his new friend, who turns out to be Editha Pastré-Schlinger, one of the novel’s main characters.

In a thoughtful afterword to this new English edition, Daniel Kehlmann cites the writer Martin Mosebach, who compares the experience of reading Doderer to attending a party: “Many things happen, you have numerous encounters, but afterward you can remember only a little, and in retrospect at once a great deal and nothing at all has occurred.” It’s the kind of party at which the guests are always looking past one another in search of someone more interesting or sexually available.

These alliances, dalliances, and deceptions are like islands of plot emerging from the sea of musings, opinions, ramblings, and extended metaphors that flood the novel. The obsessively loquacious narrator is its real main character, the biggest personality in a book full of divas. He asks a lot from us, first of all that we adjust to the novel’s alternately breakneck and glacial pace. A lot happens quickly, then nothing happens as the narrator talks and talks. Reading those pages can feel like having a mad genius whispering in your ear for days without much caring whether you’re listening—and finding it hard to break away from a soliloquy about wearing suspenders, or what it means when a character undresses before swimming.

Advertisement

Much of what the narrator says is at once lyrical and astute. “A limited imagination promotes failure of the memory,” he muses,

because there are no luminous and scarcely touched places back there in one’s past, no votive altars of a private religion, so to speak, nor small hooks in the heart attached to lines reaching far back, such that any connection at all in the imagination, or anything that one happens to see, can exercise a gentle tug.

When a married man, E.P., tells his friend Melzer about a past heartbreak, the narrator wonders what such personal confessions actually accomplish. Self-revelation is

invariably based on self-deception, on a desire to escape from one’s own center, culminating in a systematic effort to make perfectly clear to some other person, rather than to our own selves, how matters stand…. Of course he’s going to feel easier for the moment, like a sick man who changes the way he’s lying in bed. But still the emptiness remains when he looks back into the swirling, smoky cloud of his own words and is now forced to realize that it has not borne away one gram of the mass weighing on him…. They’re two jolly good fellows, Melzer and E.P., but nothing is coming out of this, at least not for them.

Not only imaginative and perceptive but vain and self-critical, the narrator apologizes for making spiteful remarks, yet can’t stop:

Melzer didn’t obtain from [Editha] even one iota of what he really wanted, albeit unconsciously—to receive back from her, now wrapped in the warmth of her person, things of his own that he’d opened up to her. (And while we’re at it, most people don’t want anything other than exactly that when they speak to us; hence the method of taking part in a conversation that will be of most benefit to all is to say back to people, with some slight variation, whatever they’ve just finished saying to us. This is the way to make the most cordial relations come about with the least expenditure of energy.)

There are also passages so obscure that I gave up trying to figure out what they meant. At times the experience is a bit like reading Pynchon; we’re pretty sure we can lose the thread and catch up with the novel later. But there is always the chance that a misunderstood reference will turn out to be crucial.

One wonders if Doderer is testing his readers or if he’s just having fun when, in the second half of the book, he introduces a series of improbable B-movie plot twists. One subplot concerns Editha’s twin sister, Mimi. First we hear that Mimi is probably dead, then that she’s definitely dead. But actually she’s alive, married, and living in Argentina. On occasion she’s been visiting Vienna, where she and Editha have been secretly swapping places. The twins are totally indistinguishable except for a faint appendectomy scar and the fact that only one witnessed and remembers the public scandal on the Strudlhof Steps. The existence of “duplicate ladies” comes as a big surprise to everyone, especially their lovers. Ultimately the twins put on identical dresses and appear together, as a joke, to shock their duped friends and victims.

The reader too is astonished to learn that it was Mimi and not Editha who precipitated one of the novel’s nastier scenes—the bullying and slapping of a vapid young would-be actress, Thea Rokitzer. In love with and “protected” by the sleazy Captain Eulenfeld, the passive, unthinking Thea followed his orders and used a stolen passport to claim, from the post office, a damaging letter that drives Editha (that is, Mimi) into in a violent rage.

Like Melzer, Thea, who has zero acting talent, is considered stupid. In a brilliant passage that captures how desire can be masked with fake contempt, the husband of Thea’s friend describes Thea as a

fruit which—provided its type attracts a man to begin with—seems to be just made to bite into as long as all one does is look at it, but if it is bitten, one can only despair of having done it, because it tastes like food in a dream—like air, that is.

Elsewhere the narrator argues that Thea is missing the two traits required by the times to be really stupid: brazenness and hostility. By now it should be obvious how much of the book still seems accurate today, how recognizable its characters. Each generation has its Captain Eulenfelds, surrounded by younger women and admiring club kids. Each group has its Etelka Stangeler-Grauermanns, imagining that the next lover will cure her sadness.

In what may be this very verbal novel’s most meaningful conversation, René Stangeler—who comes closer than anyone to speaking for the author—expounds on the metaphysics of stupidity:

The captain once said to me that a stupid person who realizes his stupidity is demonstrating great intelligence by that token alone. Such a person would even be capable of asking the question—and probably would ask it—what actual significance his own stupidity is supposed to have, why it should have fallen to his lot. The very question places him outside his limitation.

One may wonder why Doderer was so obsessed with stupidity. Facing the consequences of one’s stupid mistakes is a basic narrative arc, as it was with Adam and Eve. But evidence suggests that Doderer might have wanted to revisit his own unwise decisions. A year before his death in 1966, he wrote, “My real work consists, in all seriousness, neither of prose or verse, but in the recognition of my own stupidity.”*

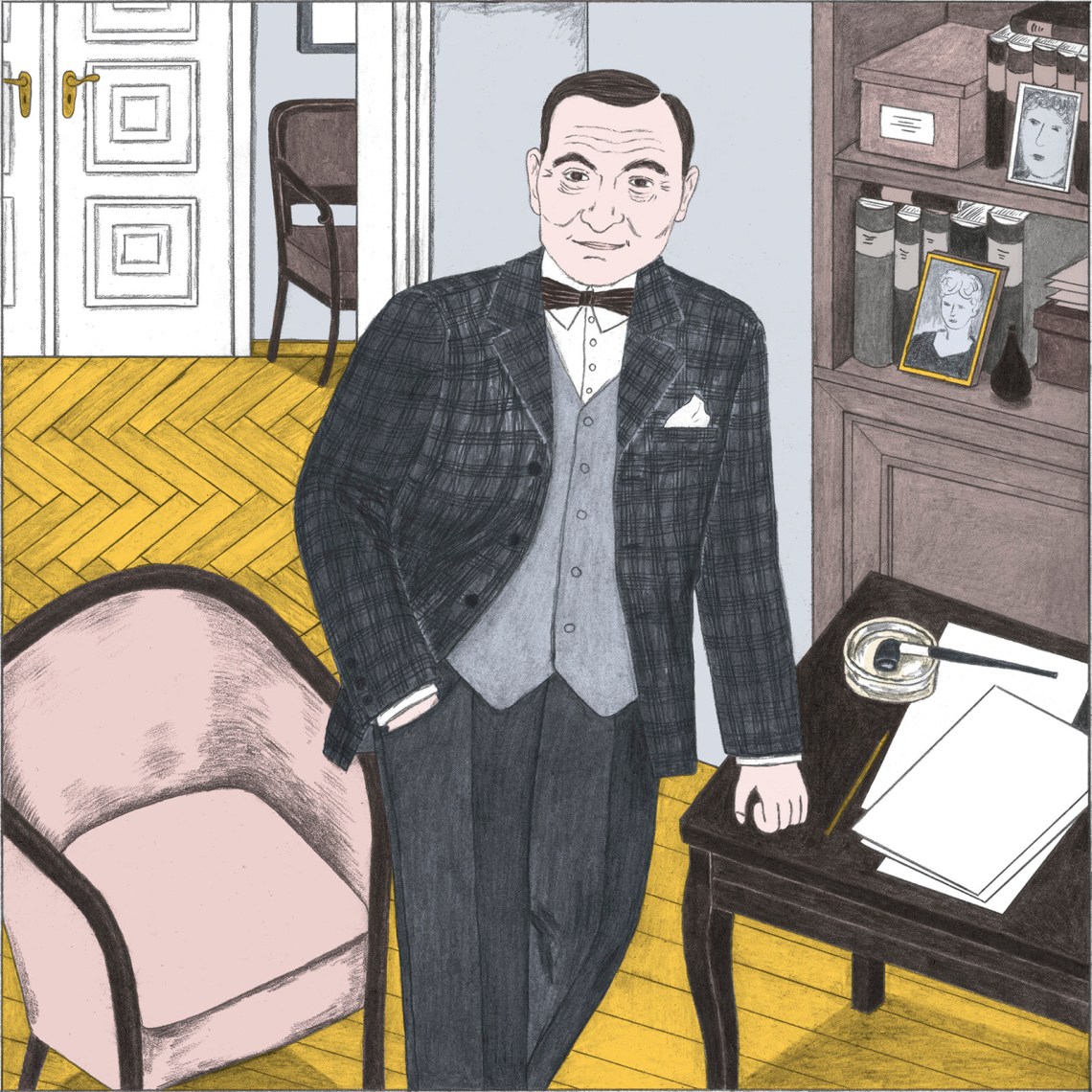

Born into a wealthy Viennese family in 1896, Doderer was recruited into the Imperial Dragoons in World War I. Captured by the Russians in 1916, he was sent to prison in Siberia. He made his way, with great difficulty, back to Vienna, where he worked as a journalist. In 1933 he joined the (then illegal) Austrian Nazi Party. Though it’s been suggested that this was an opportunistic move to aid his unpromising literary career, he appears to have been a genuine anti-Semite and believer in National Socialism. Raised as a Protestant, he converted to Catholicism in 1940, possibly as a response to his disaffection with Nazism, though he never fully repudiated the party or apologized for his loyalty to it. Recruited into the Wehrmacht during World War II, he was posted to France, then Vienna, then Oslo. (References to Oslo appear in The Strudlhof Steps.)

After the war, the denazification program prohibited Doderer from publishing. When these restrictions were lifted in 1951, The Strudlhof Steps appeared, and it became a critical and popular success. Other novels and volumes of short stories followed, most famously The Demons, translated into English by Richard and Clara Winston and currently out of print.

There is no Nazi Party in The Strudlhof Steps, though one existed in Austria after 1918. The narrator does complain about rich Eastern Europeans getting the nicest apartments, but that’s how New Yorkers talk about Russian oligarchs, and it doesn’t mean they’re fascists. There is no overt anti-Semitism in Doderer’s novel, nothing even remotely close to the odious caricatures one finds in, say, Hemingway and Wharton. In one of his stories, “The Trumpets of Jericho,” there’s a beard-pulling episode that seems coded but presumably refers to the daily humiliations visited on Vienna’s Jews; it’s horrifying, and it’s meant to be. Early in The Demons, a novelist, Kajetan von Schlaggenberg, a minor figure in The Studlhof Steps, complains about his estranged wife’s Jewish origins. In The Strudlhof Steps, Melzer tells us, “My mother doesn’t object to Jews,” but it’s not clear what he means.

One possible reason for the novel’s popularity is that it denazified Vienna and restored it to a brighter era, when, at least for the privileged, suffering entailed what Nadezhda Mandelstam called “ordinary heartbreak.”

Perhaps some readers will refuse, on moral grounds, to read an 850-page novel by an Austrian Nazi who never publicly recanted. Perhaps they’ve stopped listening to Wagner. It is, as they say, a personal choice. I was sorry to learn about Doderer’s politics, but I remained enraptured by the novel, even when it occurred to me that its author may have been denazified but not completely demilitarized. Consider the moment when Melzer saves Mary K.’s life:

Melzer turned left and raced toward the middle of the square.

Exactly like charging full on in battle: hurtling fully into it as if one’s own will were a gigantic hairy fist whose force a man has been trained all his life, however small and insignificant it has been, to receive.

At her side. With blood spurting red everywhere, spattering the man’s knees. But the man was a professional soldier, a soldier who’d weathered many different battles. He pulled off his belt and moved her shredded and bloody clothing aside. He felt around the wound, calmly and clearly realizing within mere seconds that the leg had been severed almost completely above the knee…: that’s where he applied a tourniquet. He skillfully thrust his walking stick (along with its gold knob) through his belt as he was tightening it, and now he gave it a twist. The blood that had been gushing out at even intervals now stopped.

Melzer knows what to do because he has been in the war. When your leg is under the trolley, the veteran’s the guy you want. The irony is that poor Melzer has spent years believing that the secret of intelligence is to stop thinking like a soldier. But now Melzer wins on all counts. He and Mary used to be in love, so it’s perfect that he saves her. Then the ingénue, Thea Rokitzer, shows up at the accident scene. With remarkable courage and calm, she helps Melzer administer first aid, and they fall in love as they kneel together in Mary’s blood. And so the novel’s two “stupid” characters have been brave and ingenious, saved a life, and found each other.

The novel ends—or nearly ends—with Thea and Melzer’s wedding, though the narrator can’t help mocking novels that end with marriage:

People seem to consider such a wrap-up an ending and not a beginning…. The truth is, however, that such an ending furnishes nothing but an unusually good opportunity—a splendid one, for that matter—to reinstate emptiness by way of fulfillment, removal of suspense…. Here, then, a legitimate reason becomes discernible for closing novels at the point of “happily ever after”—to leave our dear readers with the precious legacy of emptiness, even though it may last for only a brief, ideal moment, to leave them in their virginal state, as it were, and that is why the author will now slip away at this point and insist to the publisher that his manuscript is finished.

But the narrator can’t end by praising emptiness. So there’s a coda that takes us back in time to the couple’s engagement party, at which they are toasted by Civil Service Councillor Julius Zihal, the epitome of the deadly dull bureaucrat. As Vincent Kling pointed out during an informative online discussion promoting the release of this translation, the speech is a muddled version of the song from Die Fledermaus that dear Major Laska sang when he and Melzer first met on a train. “Happiness,” mumbles Zihal,

is much more likely to occupy the domain of a person the extent of whose own demands remains so far behind the decisions reaching said person from a higher quarter that a considerable residue of contentment naturally ensues.

The narrator gets the last word, telling us that it’s a perfect description of Melzer.

I was sorry when I finished the book. I’ve heard people say that when they read the last sentence of In Search of Lost Time, they wanted to start all over from the beginning. Similarly, The Strudlhof Steps invites instant rereading. You want to reenter its cinematic world, like an epic film directed by Douglas Sirk in partnership with Béla Tarr, Fassbinder, and Visconti. You want to reflect on one of the narrator’s observations that you might have missed before, to register a repeated sentence or detail that turns out to be portentous, and, this time, to be sure which of the duplicate ladies wakes up in the captain’s bed and has her passport stolen.

-

*

Ivar Ivask, “Heimito von Doderer, an Introduction,” Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Autumn 1967). ↩