In 1840 a slightly bewildered and grumpy John Quincy Adams observed in his diary that a young man named Ralph Waldo Emerson, “after failing in the every-day avocations of a Unitarian preacher and schoolmaster, starts a new doctrine of transcendentalism.” And along with this transcendentalism, Adams complained, “Garrison and the non-resistant abolitionists…, phrenology and animal magnetism, all come in, furnishing each some plausible rascality.”

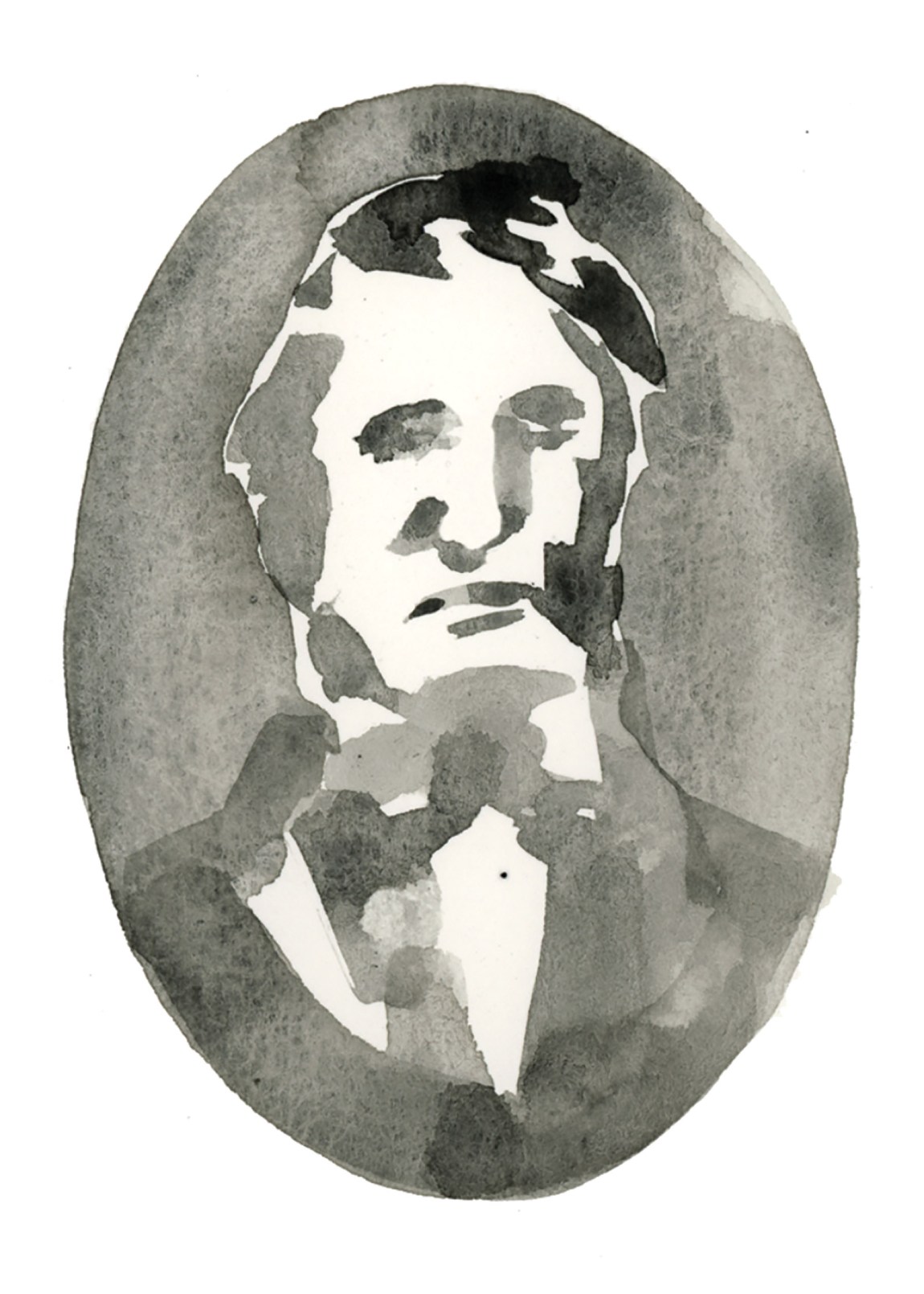

Rascality delighted Emerson. “We are all a little wild here with numberless projects of social reform,” he wrote to his friend Thomas Carlyle. “Not a reading man but has a draft of a new Community in his waistcoat pocket. I am gently mad myself.” Of course Emerson was not mad, far from it, even though some thought so after he resigned from his pulpit at Boston’s prestigious Second Church in 1832. By 1840 he was well known both as a public lecturer and as the titular head of that newfangled doctrine, transcendentalism.

If anything was a transcendental doctrine, it was Emerson’s small, powerful book Nature, published four years earlier in 1836. “As a plant upon the earth, so a man rests upon the bosom of God,” Emerson explained. “He is nourished by unfailing fountains, and draws, at his need, inexhaustible power. Who can set bounds to the possibilities of man?” Pretty heady stuff.

Heady rascals like Emerson had been seeking a more humane form of belief than what was damply offered in stodgy churches, academies, and political councils—a form of belief that squarely placed divinity in the soul of the individual, where goodness already dwelled. Unitarians may have rejected the fire-breathing Calvinist notion of original sin, predestination, and damnation in favor of a more rational and gentler view of human nature, but the transcendentalists went further: all human inspiration was divine, all nature a miracle. “The currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God,” Emerson declared in Nature. That was heretical. “Cast behind you all conformity, and acquaint men at first hand with Deity,” he then scandalously bid the graduating class at the Harvard Divinity School in 1838; he wasn’t asked to return for almost thirty years.

After Emerson’s theology school acquaintance Frederic Henry Hedge left Cambridge in 1835 to accept a pulpit in Maine, he suggested the rascals meet occasionally when he was back in town to discuss the ideas of Immanuel Kant or such topics as theology, morality, mysticism, and education. “Hedge’s Club,” also dubbed the “Transcendental Club,” met sporadically depending on who was available, and over time its members included the Reverend James Freeman Clarke, founder of the periodical The Western Messenger; the Reverend George Ripley, editor of Specimens of Foreign Standard Literature, in which he published his translations of French and German philosophy; his wife, the educator Sarah Bradford Ripley, who with her husband started the Brook Farm communal experiment in West Roxbury, Massachusetts; and the steely Orestes Brownson, considered by the historian Arthur Schlesinger to be Karl Marx’s American precursor. Also attending was the oracular teacher Bronson Alcott (Louisa May’s father), whose Conversations with Children on the Gospels scandalized proper Bostonians with its allusions to sex and eventually forced him to close his progressive Temple School. Joining them before long was the young, fierce Reverend Theodore Parker, an antislavery advocate who later kept a brace of pistols in his desk to protect Ellen and William Craft, two Black fugitives he was secretly harboring.

There were women too, and not just wives, among them Elizabeth Peabody, who taught in Alcott’s school and whose West Street foreign-language lending library and bookshop operated as an informal meeting place for the group; and the brilliant Margaret Fuller, the first editor of their publication, The Dial: A Magazine for Literature, Philosophy, and Religion. Its inaugural issue in 1840 announced their intentions:

To make new demands on literature, and to reprobate that rigor of our conventions of religion and education which is turning us to stone, which renounces hope, which looks only backward, which asks only such a future as the past, which suspects improvement, and holds nothing so much in horror as new views and the dreams of youth.

During its four-year run, The Dial published essays, poems, and reviews by Fuller and Emerson, its next editor, as well as by Alcott, the artist and poet Christopher Cranch, the music critic John Sullivan Dwight, the poets Ellery Channing and Ellen Sturgis, and Emerson’s young friend Henry David Thoreau, who occasionally attended the get-togethers. According to Emerson, all of them were surprised that a rumor began to circulate about a school of thought called “Transcendental” and equally surprised that it was pilloried as sentimental, abstract, incomprehensible. To Emerson, it was merely a point of view, and it was not really new. In one of his many Boston lectures, aptly called “The Transcendentalist,” he explained that a transcendentalist believes in inspiration, intuition, emotion, and ecstasy, all of which radiate from the individual, who is in turn immanently connected to a divine spirit and “the inviolable order of the world.”

Advertisement

Yet Emerson warned, “there is no such thing as a Transcendental party.” That would defeat the purpose. “Act singly,” he charged in his essay “Self-Reliance.” “Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.” When asked to join the Brook Farm community, he characteristically demurred. The more prickly Thoreau, when invited, declared that he’d “rather keep batchelor’s hall in hell than go to board in heaven.” Still, he boarded for a while with the Emersons in what Emerson half hoped was his own communal experiment. And though the relationship between the two men was complicated, they shared a goal: to remove us from our quiet, desperate getting and spending by revealing our connection to all living things. “Shall I not have intelligence with the earth?” Thoreau wonders. “Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself?”

Thoreau was as yet unknown, but Emerson’s reputation grew. “I had heard of him as full of transcendentalisms, myths & oracular gibberish,” Herman Melville wrote the editor Evert Duyckinck after hearing Emerson lecture. “To my surprise, I found him quite intelligible…. I love all men who dive. Any fish can swim near the surface, but it takes a great whale to go down stairs five miles or more.” Nietzsche too admired Emerson and reputedly traveled with a copy of his essays. The transcendentalists inspired people all over the world, from Charles Baudelaire to Leo Tolstoy, from Charlotte Forten to Adam Mickiewicz, and from D.T. Suzuki and Jawaharlal Nehru to Robert Kennedy. Emily Dickinson called Emerson’s Representative Men “a little Granite Book you can lean upon.” And of course Gandhi read Thoreau.

Not everyone was on board. Much as he admired Emerson “as a poet of deep beauty and austere tenderness,” Nathaniel Hawthorne said he “sought nothing from him as a philosopher,” and as for The Dial, it put him to sleep. Louisa May Alcott, in an essay humorously called “Transcendental Wild Oats,” satirized her orphic father Bronson as expecting orchards to spring from his head. Virginia Woolf’s father, Leslie Stephen, defined transcendentalism as the vague yearning for an “intellectual flying machine—some impulse that would lift you above the prosaic commonplace world,” and Henry Adams found it all hilarious. But Emerson can produce an effect of exaltation, “as though the disembodied mind were staring at the truth,” Woolf wrote. “The beauty of his view is great, because it can rebuke us, even while we feel that he does not understand.”

By and large, transcendentalism was a literary movement, which is why we continue to read Emerson and Thoreau and to a lesser extent Fuller. The prose remains. They were all conscious stylists. “The writer must direct his sentence as carefully and leisurely as the marksman his rifle,” Thoreau instructed himself in his journals. “My book should smell of pines,” Emerson exclaimed, and if he can sometimes be annoyingly abstract, often his language is succinct, precise, concrete, and unforgettable; the images fresh and flinty. “Cut these words, and they would bleed,” he writes of Montaigne. Or take his description of Socrates:

He affected a good many citizen-like tastes, was monstrously fond of Athens, hated trees, never willingly went beyond the walls, knew the old characters, valued the bores and philistines.

Socrates hated trees? And then there is the more skeptical register. “I am content with knowing,” Emerson writes, “if only I could know.” And Thoreau said, “The miracle is, that what is is, when it is so difficult, if not impossible, for anything else to be.”

“I desire to speak somewhere without bounds,” Thoreau wrote in Walden, whose style is barbed, pungent, and often expressively poignant, as in this well-known sentence, with its balanced phrases and alliterations: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Both Emerson and Thoreau revised their work over and over in order to reconcile the observable fact with something more intangible, to realize—and record—a “living poetry like the leaves of a tree…not a fossil earth but a living earth.” As Thoreau reminds us, “Not an inch of it can be spared by the imagination.”

For the transcendentalists, writing was also an ethical act, whether they were mulling self-reliance, Napoleon, the hoeing of beans, or, in the case of Fuller, the capacity of women to be more than tufted upholstery. “If you ask me what offices they may fill; I reply—any,” she wrote in Woman in the Nineteenth Century, famously adding, “Let them be sea-captains, if you will.” “We but half express ourselves, and are ashamed of that divine idea which each of us represents,” Emerson proclaims in “Self-Reliance.” His aspirational task, like that of all the transcendentalists, is thus reclamation, a spiritual awakening to the transformative power of imagination and a faith in the better, moral angels of our nature. At once democratic and aristocratic, representative and singular, they had a mission. As Thoreau announces in Walden, “I do not propose to write an ode to dejection, but to brag as lustily as chanticleer in the morning, standing on his roost, if only to wake my neighbors up.”

Advertisement

The transcendentalists, then, were writers who believed that through the word, they could inspire the self, and through the self, the country. “The use of symbols has a certain power of emancipation and exhilaration for all men,” Emerson wrote in his essay “The Poet.” “Words are also actions, and actions are a kind of words.”

“I was simmering, simmering, simmering,” Whitman memorably responded. “Emerson brought me to a boil.”

Emerson and Thoreau are the representative transcendentalists in Robert A. Gross’s The Transcendentalists and Their World, his eight-hundred-page excavation of life in Concord, Massachusetts. Drawing a circle around this New England village, population circa two thousand, where Thoreau was born in 1817 and where Emerson moved in 1834 at the age of thirty-one, Gross, an emeritus professor of history at the University of Connecticut, claims that “the American Renaissance was a town as well as a national achievement.”

The title of Gross’s book is thus somewhat misleading, for its subject is neither “the transcendentalists” as a whole (in Boston or elsewhere) nor Emerson’s and Thoreau’s transcendental fellow travelers, like Alcott and Ellery Channing, who also lived in Concord. Nor does “their world” include writers who influenced Emerson and Thoreau, such as Carlyle, the English Romantics, Goethe and Schiller, the Greek and Persian poets, or Hindu sacred texts. Rather, as Gross explains, he regards his book as a sequel to his Bancroft Prize–winning The Minutemen and Their World (1976), a social history of Concord that documents the lives of the ordinary, often voiceless members of a romanticized village where, on April 19, 1775, a shot was fired that was heard around the world.

Then, as now, Gross immersed himself in tax lists, land transfers, pension records, probate files, local newspapers, and whatever vital records were tucked away in various parishes. Even with the assistance of undergraduate and graduate “data gatherers and computer consultants” (the book contains almost two hundred pages of notes), he admits that during fifty years of research, he “could and did get lost in the abundance of materials.” Nonetheless, his intention is a “community study of Concord” that demonstrates how that community shaped Emerson’s and Thoreau’s “understanding of the broader society and culture.” At the same time, arguing that the Boston version of transcendentalism, most notably articulated by George Ripley and Orestes Brownson, “linked self-culture to social reform,” Gross suggests that the Concord transcendentalists “stood apart from the moral crusades of the day,” with Emerson reluctant to get involved in the antislavery movement and Thoreau preferring “to go his own way.”

This may be because Gross does not venture beyond the late 1840s and so does not take account of Emerson’s fierce denunciations of the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act. “Liberty is aggressive,” Emerson wrote. “It is only they who save others, that can themselves be saved,” he encouraged a friend after the failed attempt to spring the fugitive slave Anthony Burns from a Boston jail in 1854. In 1859 Emerson reportedly said that John Brown’s execution “will make the gallows as glorious as the cross.” Thoreau called Brown “a transcendentalist above all.”

Gross does successfully present the local life of Concord and its many inhabitants, including Black families. The first three hundred pages of his book teem with stories about the internecine parish conflicts, land grabs, political rivalries, and church schisms of the 1820s and early 1830s, a “dawning era of change.” Among the many characters—such as Lemuel Shattuck, John Keyes, Mary Brooks, and Samuel Hoar—is Concord’s long-lived divine, Emerson’s step-grandfather Reverend Ezra Ripley, the occupant of the gray parsonage known as the Old Manse, where Emerson briefly boarded and where he apparently wrote Nature. Hawthorne, who rented it for a short time, said, “It was awful to reflect how many sermons must have been written there.” Ripley must have written about three thousand.

To Gross, Ripley represents the desire to maintain a bulwark of shared community and institutional values to stem the divisions created by industrialization and capitalism. “The ties that once bound together the rural community frayed,” he writes, as “the chain of community was giving way to the claims of cash.” Advances in husbandry, for instance, came at a price: though beneficial commercially, the conversion of the wetlands into productive meadows, the cultivation of more marketable crops, and the use of chemical fertilizers threatened the existence of the independent farmer, who had once been part of a supportive network with a “widely held commitment to ‘good neighborhood.’”

The temperance movement too was a mixed blessing: “In the name of purifying morals, it could set neighbor against neighbor.” That in turn “set in motion” conflicts that “would prove to be a crucible for Transcendentalism,” for “as greater opportunities for some individuals opened up”—particularly through public education—“the ties of interdependence loosened still more”; Concord was “more open and less certain, more promising and less stable.”

Similarly, the populist uprising against the order of Masons represented, Gross claims, “a force for equality of opportunity and individual possibility.” Poor Reverend Ripley was on the losing side, that of the Masonic fraternity with its institutional hierarchies, elitism, and secrecy. “Nothing could be more antithetical to Transcendentalist individualism than Masonic fraternalism,” Gross observes. Again, “the stage was set for a new chapter in Concord’s history,” he writes, although he also points out that Emerson ignored the entire anti-Masonic brouhaha.

The lyceum movement also undercut the “rhetoric of community.” This new venture in popular education—part lecture bureau, part debating society—soon featured speakers who urged the audience “to shed older ways of thinking.” The abolitionist Wendell Phillips really shook the place up.

Gross admits that his Concord transcendentalists “were not alone” in deploring a nation increasingly commercialized, materialistic, pitiless, and criminal. After a mob in Alton, Illinois, murdered the abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy and tossed his printing press into the Mississippi River in the fall of 1837, even Emerson spoke out. Formerly reticent, if not dubious, about the abolitionists, in his lecture “On Heroism” he declared that “brave Lovejoy gave his breast to the bullets of a mob, for the rights of free speech and opinion, and died when it was better not to live.” In 1838 Emerson composed a public letter to President Martin Van Buren protesting the relocation of the Cherokee peoples and the seizure of their lands, and in 1844, at the commemoration of the tenth anniversary of the British emancipation of slaves in the West Indies, he described the cruelties of slavery in graphic terms and implicated the North in the perpetuation of an evil institution.

Gross is hard on Emerson, pointing out that he regretted sending that letter to Van Buren: “Emerson was loath to engage in a moral protest—what he called a ‘holy hurrah’—for its own sake, as if to put his superior sensibility on parade.” Like many scholars, he criticizes Emerson’s seeming endorsement of manifest destiny and his apparent laissez-faire optimism, particularly in his speech “The Young American”: Emerson

spared not a thought for the dispossession of native peoples nor for the disappearance of wildness in nature that Thoreau would so compellingly indict. The spread of slavery and the Cotton Kingdom never came up.

Emerson did justify himself, for better or worse. “We have our own affairs, our own genius, which chains us to our proper work,” he explained.

We cannot give our life to the cause of the debtor, of the slave, or the pauper, as another is doing; but to one thing we are bound, not to blaspheme the sentiment and the work of that man, not to throw stumbling-blocks in the way of the abolitionist, the philanthropist, as the organs of influence and opinion are swift to do.

One contributor to the National Anti-Slavery Standard identified as “G” (Sydney Howard Gay? William Lloyd Garrison?) approved of Emerson’s West Indies speech:

In all the true influence he has exerted, embraced the essential principles of Anti-Slavery, though he has not been an active worker in this special reform. When called upon to work at all, or to speak at all, he has done both with and for the Abolitionists, and not against them, as has been the case with some who have claimed to be governed by the Anti-Slavery sentiment.

As the scholar Albert von Frank has pointed out, Emerson’s vacillation and early silences should not keep us from understanding the ways in which his ideas made a difference to the abolitionists, and no amount of scolding will deny his influence as a social thinker and slippery writer who believed that the time for revolution had come. “This time, like all times,” Emerson said, “is a very good one, if we but know what to do with it.” He was of the party of hope.

Gross is far more sympathetic to Thoreau, praising him for his need to “get back to basics” and “go it alone.” He had “shown his mettle” in the summer of 1844, when the Concord ministers had refused to let their meetinghouses host the West Indian emancipation ceremonies. Since the sexton of the First Church would not ring the church bell to alert the crowd to assemble at the courthouse, Thoreau entered the belfry and pulled the rope himself. That “independent course,” Gross claims, somehow inspired Thoreau—that and Emerson’s suggestion that he undertake his experiment in self-reliant living on the land Emerson had just purchased near Walden Pond.

To Gross, Thoreau bids other people “pare their needs, curb their wants, and follow nature’s way.” And yet what are the ways of nature? Thoreau noted that “no humane being, past the thoughtless age of boyhood, will wantonly murder any creature, which holds its life by the same tenure that he does.” Though he loved the wild in nature no less than the good, he staked his life on the higher, more evolved side of being. He left the woods after his two-year experiment; leaving Walden was as important as his going. “Perhaps it seemed to me,” he wrote, “that I had several more lives to live, and could not spare any more time for that one.”

Gross says Thoreau emerged from the woods with the first draft of a manuscript that was “the record of one man’s rebirth and the story of an American town.” In detailing the life of that town—its lyceum, its reformers, its farmers—Thoreau “never sloughed off the heritage of Ezra Ripley and the message of community” because, Gross claims, in the end, “in his mind he was never alone. The community came with him.”

Though Gross emphasizes only the manuscript that Thoreau composed during his stay in the woods, he reworked that draft seven times before the final, eloquent creation, Walden, was ready for publication in 1854, eight years later. Searching for some basic spiritual order beneath the flux of the everyday, some order of meaning outside of time and certainly outside of place (even Concord), he, like Emerson, was a careful verbal architect whose prose is ferocious, angular, unsettling, and lastingly lyrical. “I am thankful that this pond was made deep and pure for a symbol,” he concludes. As a symbol, so it remains, shimmering, bottomless, and elusive. Or as Emerson once observed, “What is fit to engage me and so engage others permanently, is what has put off its weeds of time & place & personal relation.”

Since Gross’s passion lies in the transitive, not the literary, quality of Emerson and Thoreau, he meticulously entangles them in time and place; to him, they’re historical sojourners in civilized life, rooted among facts and figures. During a ten-month period in 1812 Ezra Ripley purchased more than four gallons of rum, brandy, cognac, and wine, which means he was no teetotaler. All well and good. It may be a good idea, too, to heed Thoreau: “If you stand right fronting and face to face to a fact, you will see the sun glimmer on both its surfaces.”