Imagine a government divided between two ferociously opposed political forces, both of which claim the right to power. A crisis develops, with many officials caught between the two sides, confused and uncertain which to support. There are threats of violence, previously inviolable political spaces are invaded, and blood is shed. Anxious onlookers predict civil war. The United States experienced a crisis of this sort on January 6, 2021, when pro-Trump rioters attacked the Capitol to halt the certification of Joe Biden’s election as president.

The pattern is a familiar historical one, but such crises have often had far more devastating outcomes than the one in Washington did. In England in the 1640s, King Charles I dramatically invaded the meeting hall of Parliament in an attempt to arrest its insubordinate leaders. In Russia in 1917, Bolsheviks stormed the headquarters of the Provisional Government in the name of the popular councils called Soviets. In both cases, an enormously destructive civil war followed.

Then there was the crisis immortalized by its date in the short-lived French revolutionary calendar: 9 Thermidor Year II (Sunday, July 27, 1794). On that day, the National Convention—the effective revolutionary government—voted to purge several of its members, most prominently the radical leader Maximilien Robespierre. The men managed to escape to the Paris Maison Commune (the revolutionary name for the Hôtel de Ville, or city hall), where the municipal government, proclaiming itself the true representative of the French people, called for an insurrection.

Both sides appealed to the urban militants known as sans-culottes. After hours of considerable confusion and scattered violence the Convention prevailed, and the next day Robespierre and his allies went to the guillotine. This spelled the end of the most radical phase of the French Revolution, which the victors quickly labeled the Terror. Civil war did not follow, but revolutionary turmoil continued, and five years later Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in a coup d’état.

The victorious “Thermidorians” said they had acted to protect France from a monstrous, bloodthirsty dictator, but in truth the day boasted few heroes. Still, it did pose, very explicitly, a central question of modern democratic politics: Do militants who claim to speak for “the people” ever have the right to defy or perhaps even overthrow democratically elected governments, as Robespierre and his allies tried to do? The rioters who stormed the US Capitol on January 6 asserted that, because elected federal and state governments had acted in a corrupt and tyrannical fashion by allowing Democrats to steal the presidential election, true patriots had no choice but direct action in the people’s name. In this case their claims were outrageously and transparently false.

But during the French Revolution, matters were not always so clear. Notably, on August 10, 1792, sans-culottes and other radical militants stormed the Tuileries Palace and overthrew the constitutional monarchy established less than a year earlier. King Louis XVI had in fact been plotting against the Revolution—in June 1791 he had even tried to flee the country and join up with an enemy army across the frontier. The August insurrection led to the proclamation of the First French Republic, which most French people today regard as the legitimate and even heroic ancestor of their own Fifth Republic. The sans-culottes took up arms at several other points during the Revolution, and many of the French look back on these risings, too, with considerable sympathy. On 9 Thermidor, it was the failure of most sans-culottes to back the municipality’s call for insurrection that, more than any other factor, spelled Robespierre’s doom.

The story of the Ninth of Thermidor has been told many times, but never so well as in Colin Jones’s The Fall of Robespierre. Jones offers a new interpretation of the events, but this is not what makes his book remarkable. He has chosen to take his readers through the day literally hour by hour, starting at midnight and ending at midnight, although with a considerable epilogue for the following day. The chapters, some no more than a paragraph long, all begin with a time stamp and are written in the present tense. Jones has marshaled a huge cast of characters but interweaves their stories deftly, allowing the reader to follow along with ease. He also has an eye for the telling detail—the way a man’s handwriting “gets wild and shaky as he scribbles down his orders”; a deputy recklessly demanding to be arrested along with Robespierre, and his friends “surreptitiously…tugging at his coat-tails to force him to sit, so firmly in fact that his jacket has torn.” And Jones can summon up striking and humorous turns of phrase. Robespierre has “egg-shell amour-propre”; “There is nowhere that [Bertrand] Barère feels more comfortable than on the fence.”

Jones’s narrative experimentation is all the more welcome because it is so uncommon in his field. Few historians today consider history a literary art as well as a scholarly exercise, and most hew to an unimaginative expository style that has changed little in the past century—as Hayden White pointed out, to little avail, nearly fifty years ago. Jones, in his acknowledgments, claims inspiration from the Oulipo group, twentieth-century French writers who sought to produce striking literary effects with various forms of “writing under constraint.” George Perec’s novel An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris consists entirely of observations from a specific location over three consecutive days, complete with date and time stamps at the start of each section. The three hundred pages of his A Void (in French, La disparition) do not contain a single letter “e.” It will not escape connoisseurs of classic French theater that, like Racine and Corneille, Jones has also divided his text into five acts and obeys the three classical unities of time (a single day), place (the city of Paris), and action (the fall of Robespierre). Like the tragic playwrights, he manages to generate considerable suspense, even though the audience knows the bloody outcome in advance.

Advertisement

Jones was fortunate to draw on one of the richest seams of information that we possess about any eighteenth-century event. In its aftermath, the Thermidorians called on Parisian officials to send in detailed reports on what had transpired, and nearly two hundred responded. An official commission also produced a report, in addition to which voluminous memoirs, newspaper accounts, and police dossiers have survived, along with transcripts of proceedings in the Convention. Jones has mined this material in a meticulously judicious fashion. Unlike many historians of the French Revolution, he has no desire to fight its battles over again. His Robespierre is neither the blood-drenched monster of Thermidorian legend nor the visionary hero that some on the French left still believe him to have been. He is a complex character: idealistic and inspiring, but also rigid, ruthless, thin-skinned, and increasingly paranoid; a brilliant thinker and strategist, but a terrible manager who lacks any sense of how to lead others in a crisis.

Jones’s weaving of a coherent narrative also benefits from the fact that the events mostly played out in a very small area—barely a square mile of central Paris, along what are now just four stops of Metro Line One. Nearly all the participants lived and worked there. The execution of Robespierre and his allies took place just to the west, in what is now the Place de la Concorde. Today wide, airy boulevards cut through this area, but in the late eighteenth century it was a maze of small, dark streets that were unbearably fetid in the summer heat of Thermidor. Even so, news and messages could spread in a matter of minutes, and a tocsin of church bells could sound an immediate alarm.

The start of the book poses the greatest challenge for Jones. Because of the constraint he has imposed on himself, he must recount the surprisingly busy early-morning hours of 9 Thermidor while at the same time introducing his characters and providing background for the events that were starting to unfold. This background was anything but simple. French people frequently remarked that since the start of the Revolution in 1789, time seemed to have become compressed, so thick was it with events. Robespierre, barely a month before his fall, wrote that in the previous five years, the French had leapt two thousand years ahead of the rest of the human race. These chapters occasionally make for heavy going, but Jones leavens them with considerable humor and piquant detail. He notes that a deputy in prison, threatened with execution, nonetheless managed to live luxuriously, requesting “salad, cabbage, carrots, asparagus, artichokes, grapes, chocolate, sugar lumps, mackerel, sausages, grilled songbirds, rice, pork and mutton, a bottle of wine a day.” Introducing Robespierre’s somewhat dim younger brother Augustin, Jones quotes another revolutionary’s devastating verdict: “All lungs, no brain.”

The density of events stemmed from a process of apparently unstoppable radicalization. In 1789, most of the French had assumed that the Revolution would quickly conclude with the transformation of the country’s absolute monarchy into a moderate constitutional one. Instead, ferocious political battles developed over the pace and extent of reform, with outbreaks of popular violence repeatedly breaking stalemates between more conservative and more radical political factions in the latter’s favor.

By the spring of 1793, the old regime’s legal structure had been largely swept away, the king had been executed, the Catholic Church had seen its property expropriated and its privileged status abolished, and a republican National Convention elected by universal adult male suffrage was trying to rebuild the country almost from scratch. France was also at war with a large pan-European coalition, and a dangerous revolt was out of control in the western departments. The Convention itself fell prey to bitter factional infighting, and at the end of May 1793 a radical group around Robespierre, nicknamed the Mountain (they occupied the highest seats in the meeting hall), forged an alliance with sans-culottes who staged an armed insurrection and forced the expulsion and imprisonment of rival Girondin deputies.

Advertisement

Over the next year the Convention’s Committee of Public Safety, dominated by members of the Mountain, assumed increasingly dictatorial powers in order to fight the war and the civil war, and to eliminate alleged counterrevolutionaries. Their campaign of bloody repression accelerated dangerously in the spring of 1794, when thousands of men and women were hauled before a hostile Revolutionary Tribunal, often on flimsy charges, and in many cases executed after perfunctory trials.

Robespierre, the dominant figure on the Committee, purged enemies on both the right and the left, including the great revolutionary orator Georges Danton, who went to the guillotine in April. By 8 Thermidor, many other deputies were fearing for their lives, and on that day, Robespierre gave a violent, two-hour speech in which he promised further purges. Worn down by the crushing demands of revolutionary politics, assassination threats, and recent illness, he was nonetheless capable of remarkable flights of eloquence and remained something of a popular idol. Several other members of the Committee now suspected that they had become his targets.

Jones argues that while Robespierre was almost certainly planning a new purge of the Convention, he did not intend for it to happen immediately. Armed support from the sans-culottes could take weeks to organize. Nor were his possible victims ready to act against him. What happened on 9 Thermidor was in large part a chaotic, confused accident. With his careful, minute-by-minute reconstruction, Jones shows just how much depended on sheer chance, on odd twists of fortune, and on “a million micro-decisions made by Parisians across the expanse of the city and through the 24 hours of the day.”

At the center of the events, improbably, was a romance. Theresa Cabarrus was the beautiful twenty-year-old daughter of an aristocratic Spanish financier—and therefore, in the eyes of radical revolutionaries, an enemy aristocrat herself. But a twenty-seven-year-old member of the Convention, Jean-Lambert Tallien, while leading a mission to suppress and punish provincial counterrevolutionaries, had fallen in love with her and protected her. In early 1794 Robespierre and his allies started to accuse Tallien of “moderationism,” or an insufficiently hard-line attitude when it came to the guillotine. For the moment, his status as a deputy shielded him, but not Cabarrus, who was imprisoned on Robespierre’s orders. By 8 Thermidor her trial and execution looked imminent. Frantic to save her and fearing for his own life, Tallien spent the early-morning hours of 9 Thermidor crisscrossing the center of the capital, visiting deputies and imploring them to join him in attacking Robespierre in the Convention.

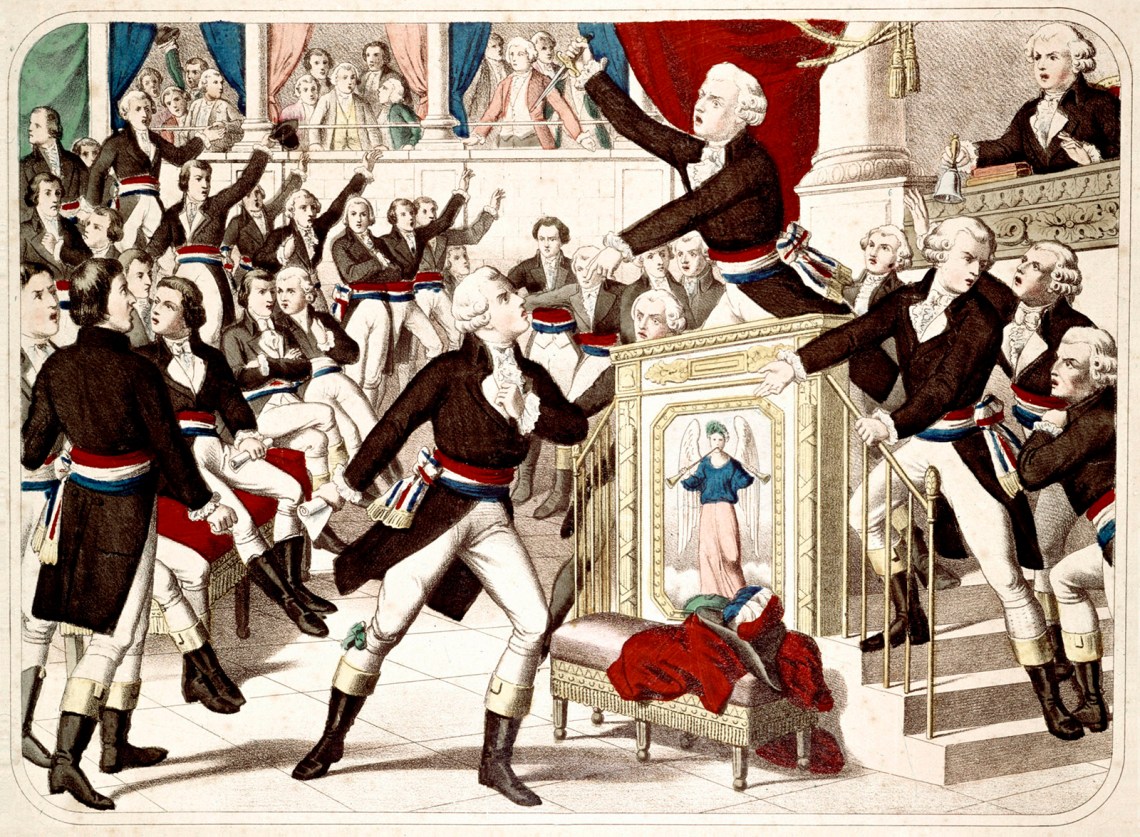

The crucial moment came shortly after noon, in the Convention’s meeting place: the Tuileries Palace in central Paris (adjacent to the Louvre, it was destroyed in the nineteenth century). Robespierre’s closest ally, twenty-six-year-old Louis-Antoine Saint-Just, was giving a speech when Tallien burst into the hall, demanding to speak on a point of order. A sympathetic chair let Tallien have the floor, and he immediately attacked Robespierre for seeking to hurl the country “into the abyss.” Theatrically, he whipped a dagger out of his coat, promising to kill Robespierre if the Convention did not order his arrest.

Tallien’s newly recruited allies shouted their support and, emboldened, the threatened members of the Committee of Public Safety joined in the attack, denouncing Robespierre as a tyrant. He tried to get to the rostrum to speak, but deputies physically blocked his way. For nearly two hours, Robespierre struggled to make himself heard, while deputy after deputy, sensing the sudden change in the wind, denounced him. Finally, the Convention ordered his arrest, along with that of his brother, Saint-Just, and several others.

But the day was far from over. Robespierre had always counted on staunch support from the Commune—the municipal government—of Paris. Its leaders, in turn, had the ability to mobilize armed detachments of sans-culottes and other militants from the forty-eight districts of the city. A crucial figure was François Hanriot, the foul-mouthed, choleric commander of the Parisian National Guard. When news of the Convention’s actions reached the Maison Commune, Hanriot called for an uprising and sent a messenger from the Convention back with the words “we are going to hurry along to rid them of all the fucking traitors to the fatherland.”

As policemen delivered Robespierre to the gates of the Luxembourg prison, a crowd forced his release, and municipal officials brought him to the Maison Commune. By early evening, over three thousand armed men had assembled there, while the Convention remained largely undefended. One official declared that “the Convention only exists in the form of a factious few. The people has taken the reins of government.” It seemed that Robespierre and the Commune might yet win the day.

In the evening, the tide turned. Although used to taking up arms for the Commune, the sans-culottes had until now also given enthusiastic support to the Convention, under whose leadership France’s armies had recently scored major military victories. Conflicting messages from the two institutions left many of the district assemblies in confusion. But the Convention acted more quickly to print and distribute wall posters and broadsheets denouncing Robespierre and the Commune for conspiring against the Revolution.

In addition, at a crucial moment, Hanriot flinched from ordering a full-scale assault on the Convention—possibly, Jones suggests, because “beneath Hanriot’s bravura exterior beats a cowardly heart.” Robespierre, in a state of shock, failed to rally his followers despite having written, in a 1793 Declaration of Rights, that “when the government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is for the people and for each portion of the people the most sacred of rights and the most indispensable of duties.” He began to sign a document demanding armed action against the Convention and then stopped, leaving just the letters “Ro” (it survived and can still be seen in the French National Archives).

Meanwhile, the Convention named Paul Barras, a tough, experienced deputy and former military officer, to organize its armed response. It also formally declared Robespierre, his allies, and the leading municipal officials to be outlaws, subject to immediate execution without trial (in doing so, ironically, it relied on legislation originally pushed by Robespierre himself). By midnight, and the end of 9 Thermidor, the Commune’s supporters were hedging their bets and returning home, while the Convention prepared its own assault. Two hours later, Barras’s men stormed the Maison Commune and met little resistance. One of Hanriot’s subordinates, furious at his erratic conduct, threw him out of a window onto a dung heap. Robespierre sustained a dreadful bullet wound to the jaw—possibly self-inflicted in a botched suicide attempt. Less than twenty-four hours later, he, Saint-Just, Hanriot, and nineteen others went to the guillotine. Eighty-three more men, mostly municipal officials who had supported the attempted insurrection, followed over the next two days.

The meaning attached to this incredible story has changed significantly over time, and Jones has revised it yet again. In the immediate aftermath of 9 Thermidor, the victors portrayed what had happened as the joint triumph of the Convention and the people of Paris over a bloodthirsty tyrant. By 1795, however, they were trying to move the Revolution away from egalitarian social reform, writing a new constitution that would limit suffrage to men of property, and brutally suppressing two attempted insurrections by the sans-culottes. In accordance with these new positions, they cast 9 Thermidor as an action by the Convention alone to stop a radical movement that had careened out of control into what they now labeled the Terror. Inventing two words with an impressive future, they condemned “terrorism” and sent additional “terrorists” to the guillotine, while writing the people of Paris out of the story entirely.

Modern historians have, to a surprising extent, followed their lead, arguing that the people of Paris failed to save Robespierre because they had been shell-shocked by the Terror or disapproved of the Mountain’s attempts to rein in the volatile sans-culottes. Jones will have none of this. “Parisians might have tired of Robespierre,” he writes convincingly, “but they had not tired of political life.” The Ninth of Thermidor played out the way it did because militant Parisians, in the chaos and confusion of the day, ended up supporting the Convention over the Commune. Doing so required them to believe that Robespierre, until then their hero, had been unmasked as an evil counterrevolutionary. But Robespierre himself had made this reversal easier by supposedly unmasking many earlier revolutionary heroes, most prominently Danton, in the same fashion. He was devoured by the machine of terror he had done so much to set in motion.

If Jones’s book has a weakness, it is that the imaginative focus on a single day makes it harder to see 9 Thermidor in the larger setting of the Terror. He reinforces this tendency by deferring to recent French scholarship (notably by Jean-Clément Martin) that questions older understandings of the Terror as a concerted national campaign of bloody repression that spun madly out of control and ended with 9 Thermidor. This new work puts emphasis on the post hoc invention of the term “Terror” by the Thermidorians, on the highly uneven patterns of repression across France, on the fact that many victims were armed rebels against the Convention, and on the continuation of widespread if more spasmodic bloodshed throughout the rest of the 1790s, including brutal episodes of revenge against radical officials and their allies.

However one understands the Terror, though, it is important to recognize that something horrific took place in France in the year before 9 Thermidor and came to an end as a result of it. During that year, the Convention decreed that anyone fitting into a broad category of “suspect,” including anyone who had allegedly written or spoken against the Revolution, was subject to immediate arrest and trial. Aided by a network of thousands of Jacobin societies implanted even in small villages, the authorities imposed a regime of draconian surveillance in much of the country and encouraged anonymous denunciation. Newspapers were shut down or intimidated. Robespierre boasted that “every new faction will discover death in the mere thought of crime.”

In the rebellious west of the country, the army carried out indiscriminate mass killings, with an overall death toll that may have exceeded 200,000. In the spring of 1794, the Convention stripped political defendants of most legal protections and streamlined trial procedures, greatly accelerating the pace of executions. It was not just Robespierre’s enemies in the Convention who lived in constant fear during this time. Jones quotes a conversation between an apprentice printer and friends that was recorded by police spies: “‘If they guillotine people just for thinking, how many people will die?’ ‘Don’t talk so loud. They could hear us and take us in.’”

The men who overthrew Robespierre had participated in this repression. They ended it in large part to save their own heads and to prepare the way for the more conservative revolutionary government they established in 1795. But end it they did—not immediately and not fully, perhaps, but untold numbers of lives were saved. Had the Commune succeeded in its insurrection on 9 Thermidor and returned Robespierre and his allies to a position of dominance, there is little doubt that the bloodshed would have increased dramatically. Tallien and his impromptu allies on the Committee of Public Safety may have been anything but righteous, but it does not always take righteous people to accomplish a righteous end.

And legality, in the end, also mattered. The Convention may have forfeited much of its claim to legitimate authority by its deliberate destruction of legal norms over the previous year, but it remained the elected government of France, chosen for the first time in European history by universal adult male suffrage. The insurrectionary Parisian officials had no legal basis to argue that “the people has taken the reins of government”—only their own conviction that they incarnated the true spirit of the Revolution better than their opponents did. On very rare occasions, when an elected government has entirely forfeited its legitimacy, violent insurrection may be justified. On 9 Thermidor Year II, as on January 6, 2021, it was not.