As I read 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, I felt as if I’d finally come upon the chronicle of modern China for which I’d been waiting since I first began studying this elusive country six decades ago. What makes this memoir so absorbing is that it traces China’s tumultuous recent history through the eyes of its most renowned twentieth-century poet, Ai Qing, and his son, Ai Weiwei, now equally renowned in the global art world. It guides us from Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist era in the 1930s, through Mao Zedong’s revolution in the 1950s and 1960s, and on to the “reform era” of Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s and Xi Jinping’s current Leninist restoration, explaining how, as Ai Weiwei writes, “the whirlpool that swallowed up my father upended my life too, leaving a mark on me that I carry to this day.”

After studying in Paris, Ai Qing returned home in 1932. However, before the decade was out, he’d begun to have one malefaction after another inflicted on him by Chiang’s and then by Mao’s regime. First, his strong views on the importance of intellectual and artistic independence got him accused by the Nationalists of “damaging the republic” and sentenced to six years in prison. In 1938, during the Japanese occupation, he’d written in On Poetry (诗论):

Poetry today ought to be a bold experiment in the democratic spirit, and the future of poetry is inseparable from the future of democratic politics. A constitution matters even more to poets than to others, because only when the right to expression is guaranteed can one give voice to the hopes of people at large…. To suppress the voices of the people is the cruelest form of violence.

He was released from jail in 1935. Then, in 1941, he fled to Yan’an, Mao’s Communist redoubt in China’s desolate northwest. But this so-called “liberated area” hardly proved the “paradise of equality, freedom, and democracy” for which he’d hoped, and soon his free-spirited idealism put him at cross-purposes with Mao as well. Ai Weiwei recounts how his father naively argued with Mao that literature and art cannot be “a gramophone or a loudspeaker for politics” but must instead find “expression in their truthfulness.” Unfortunately he had no way of knowing that Mao was just then readying a major political “rectification campaign (整风运动)” against “incorrect thought (错误思想)” that would make self-expression among Communist intelligentsia as taboo in the arts as in politics.

In fact, Mao’s 1942 treatise, The Yan’an Forums on Literature and Art, which formed the basis for this movement, has guided the party’s quest for ideological unity ever since its publication. Under its shadow, writes Ai Weiwei, “everyone sank into an ideological swamp of ‘criticism’ and ‘self-criticism’” in which the bourgeois tendencies of his father’s art marked him indelibly as being politically unreliable.

Ai Weiwei was born in 1957, just as a high tide of Maoist political campaigns was upending every aspect of Chinese life. When the previous year Mao launched the Hundred Flowers Campaign encouraging intellectuals to speak out, Ai Qing did exactly that. But when Mao halted the campaign as suddenly as he’d started it and launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign pillorying the very critics he’d just emboldened, Ai Qing paid grievously for his frankness. After being dubbed a “counter-revolutionary bourgeois rightist” and “an enemy of socialism,” he was dismissed from all his positions and expelled from the party, so that even old friends began avoiding him. Then, like half a million other intellectuals, he was “sent down (下放)” to the Great Northern Wilderness (北大荒) along the Russian border to a “reform through labor (劳动改造队)” brigade that was part of Mao’s sprawling version of Stalin’s Gulag. Ai Weiwei, then only two, accompanied him, while the rest of the family came later. He would spend the next two decades with his father, in effect a juvenile political prisoner in internal exile.

After Mao launched the Great Leap Forward in 1959 to reorganize rural China into “people’s communes (人民公社)” and precipitated one of the worst famines in Chinese history, the Ai family was moved for further “remolding” to a still more godforsaken place of exile: Xinjiang, China’s westernmost desert province. There they were remanded into the hands of the Xinjiang Military District Production and Construction Corps (新疆生产建设兵团), the same paramilitary apparat that is today building “reeducation camps” for Muslim Uighurs. In this “Little Siberia” they were assigned to the wretched settlement of Shihezi, which was filled “with other political outcasts whose only solace was forgetting.” But even here Ai Qing tried to continue writing poetry. However, because he’d been branded a “rightist” and no editor dared publish his work, he began working on a fictionalized version of the family’s life in Xinjiang instead.

No sooner was Ai Qing’s “rightist” label removed in 1961 than Mao began to foment more mass movements against a so-called “bourgeois restoration.” As a free-spirited poet Ai Qing was exactly the kind of “bourgeois element” Mao now wanted to extirpate. “The world could not be put to order,” writes his son, “without first being thrown into chaos.” For as Mao had proclaimed, “Without destruction there can be no construction (不破不立).”

Advertisement

As China careened toward the Cultural Revolution, Ai Qing found himself under renewed attack. Red Guards put banners outside their shack that read, “Expose Ai Qing’s True Counter-Revolutionary Colors!” Then the sons and daughters of many other exiled “literary types” who’d once been regular guests in the Ai home began ransacking their house.

“Now that the political storm had arrived, they were first to trim their sails to the wind, betraying and slandering people around them, in the hope of enhancing their own position,” writes Ai Weiwei. Things became so desperate that Ai Qing was driven to burn his remaining books, papers, photos, and letters. The loss of his father’s most precious things would, his son recalls, “forever impoverish my imaginings of family and society.” “At the moment they turned to ash,” he remembers,

a strange force took hold of me. From then on, that force would gradually extend its command of my body and mind, until it matured into a form that even the strongest enemy would find intimidating. It was a commitment to reason, to a sense of beauty—these things are unbending, uncompromising, and any effort to suppress them is bound to provoke resistance.

As the Cultural Revolution reached its apogee in 1967, Ai Qing was being paraded through the streets of their labor camp in a dunce cap and mocked at “denunciation meetings (批斗大会).” And to remind the Ai family that politically speaking they belonged to the lowest of the low, they were forced again to move, this time into a primitive “underground dugout (地窝子)” on the edge of the desert.

It was not until 1975 that Ai Qing was finally allowed to return to Beijing, and then only for medical treatment. But he was by then a broken man. Ai Weiwei soon followed. “One of my father’s eyes was blind and the other was nearly clamped shut in reaction to the bitter cold,” he writes of walking through Tiananmen Square with him one winter day.

He was an old man, with no fixed home and no apparent prospects for improvements in his life. He stood alone under a gray sky gazing around in grief and loss. The atmosphere in the square was heavy with sadness….

I was now nineteen, and though my ideas were often fuzzy, on one point I was clear: nobody could possibly look forward to a change more than I did. Anything would be better than the current state of affairs…. The entire society was stifled, depressed.

In 1978 the party decided to officially “rehabilitate (平反)” many “Rightists,” Ai Qing among them. After all, as Deng Xiaoping began opening China up, more and more foreigners were arriving in Beijing and asking after its most celebrated twentieth-century poet. So the party leadership not only restored Ai Qing to his former positions, it even gave him a proper house. The absurdity of first seeking to destroy him for decades only to later “rehabilitate” him without explanation was not addressed. Ai Weiwei wryly observes, “Never forget that under a totalitarian system cruelty and absurdity go hand in hand.”

As Ai Qing began trying to write poetry and essays again, his nineteen-year-old son was looking for a path of his own. In Beijing he’d begun drawing and painting, because “it offered the prospect of self-redemption and a path toward detachment and escape.” And he soon started to think of becoming an artist. Then he was admitted to the newly reopened Beijing Film Academy. However, he’d been so deeply affected by his experience in the camps that he never felt comfortable in this elite school. “I did not fit in with the new post-Mao order any more than I had fit in with the Maoist order that had shaped—or deformed—my childhood,” he writes. He found the “spinelessness and hypocrisy of Beijing society repellent.”

So, as his father was feeling more fulfilled after his rehabilitation, Ai Weiwei was “moving in a different direction and becoming more disenchanted.” He says he was feeling “untamed blood flowing through my veins: it came from the endless desert, from the white salt plains, from the pitch-black dugout and the helplessness of those long, humiliating years.”

In 1979 the fifteen-year prison sentence given to the Democracy Wall activist Wei Jingsheng deepened Ai Weiwei’s “understanding of the cynical and brutal nature of the Chinese state, and the Communist Party’s fundamental opposition to freedom of expression.” Of Deng’s reforms, Ai Weiwei remarked to one interviewer, “I could see so many luxury cars, but there was no justice or fairness in this society.”

Advertisement

Desperate for a different environment, Ai Weiwei decided to seek permission for “self-funded study” abroad. Only after he overcame endless obstacles—including a course in mandatory “patriotic education” and a “training in keeping secrets”—did the Chinese government grant him permission to leave. “I wasn’t going to America because I hankered for a Western lifestyle,” he remembers. “It was more that I couldn’t stand living in Beijing anymore.”

In 1981 he left for the US. In New York he did sidewalk art in Greenwich Village for handouts, befriended Allen Ginsberg (who admired his father’s poetry), enjoyed what he describes as “a boundless expanse of aimless and unstructured life,” and learned from Andy Warhol’s example how to arm himself with a camera as a way to document the moment, the political protests, the police violence, and the counterculture around him to bear witness to injustice.

In 1989, after watching the events in Tiananmen Square unfold on CNN, he marched and staged a hunger strike in front of the UN. But he also soon became “increasingly weary” of his situation in New York. “Freedom with no restraints and no concerns had lost its novelty,” he writes. “People said I would be the last person to go back to China, and I thought the same. But we were all wrong.” Although he claims to have had “no illusions about my native land,” he finally could not completely escape its pull. Besides, things seemed to be changing in China, and he wanted to see his aging father again.

So in 1993, after twelve years abroad, he returned home and immediately fell under the tutelage of his younger brother, Ai Dan, who introduced him to the outdoor antiques markets that had sprung up around Beijing. Soon he was collecting miscellaneous traditional artifacts. “We were still living in a culturally impoverished era,” he writes, “but art had not abandoned us—its roots were deeply planted in the weathered soil.” They were also planted within Ai Weiwei. After having first been excluded and then absenting himself from his own society for so many years, collecting things from China’s past was a way for him to reattach himself. But it was an ambivalent reconnection, as he graphically illustrated in the triptych he shot of himself willfully dropping and shattering a Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) clay pot. Then he painted a Coca-Cola logo on another pot, stunts that many saw as cultural desecrations. “These little acts of mischief,” he writes, “marked a starting point in my reengagement with the making of art.”

Such provocative artworks were attracting more and more official attention. As Ai Weiwei tried to reintegrate himself into Chinese life, he was also concluding that whereas the party was all about convincing people to toe its “correct line (正确路线),” his conception of an artist was about becoming a person who would “make no effort to please other people.” Art should be “a nail in the eye” that “destabilizes what seems settled and secure.” He’d become even less ready to fit into the existing scheme of things than before. “No matter how strong a power,” he writes, “it can never suppress individuality, stifle freedom, or avert contempt for its ignorance.”

Despite his aversion to Tiananmen Square, he found himself going there “again and again, as though drawn by some irresistible force.” If it was the symbolic center of China, it also evoked such “a mixture of helplessness and humiliation” that in 1995 he shot what was to become one of his most confrontational and famous works of art: a photo showing him giving Tiananmen Gate and its giant portrait of Mao the finger. Caught in what Mao would have characterized as “an antagonistic contradiction (敌我矛盾)”—one that could not be solved without conflict and struggle—Ai Weiwei viewed this “unambiguously scornful gesture” as an admonition to all those who “learn submission before they have developed an ability to raise doubts and challenge assumptions.”

Henceforth he refused to remain silent. “It’s a painful fact,” he writes, “that today, as we import science and technology and Western lifestyles, we are unable to introduce spiritual enlightenment, or the power of justice, or matters of the soul.”

After his father’s death in 1995, Ai Weiwei’s artistic career began taking off. At the same time, he was also becoming more resolute in his opposition to injustice. “My inspiration and boldness came from disgust and exasperation, from the dogged resilience that New York had nurtured in me, as well as my impatience with the timidity of my father’s generation,” he writes. “Now I had no intention of hanging back. I openly declared my opposition to the status quo, reaffirming, through the act of non-cooperation, my responsibility to take a critical stance.”

In the relatively open climate of the 1990s Beijing art scene, he was chosen to represent China at the 1999 Venice Biennale. He also published several art books and set up an architectural firm, FAKE Design, that worked on the National Stadium (the Bird’s Nest) for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. But nothing he did could resolve the fundamental contradiction between China’s one-party state and his stubbornly independent spirit. “Civil society poses a challenge to autocracy, and therefore, in the eyes of our rulers, it is an object of fear,” he writes. “The Chinese government, accordingly, seeks to erase individual space, suppress free expression, and distort our memory.”

In his endless joust with the party, Ai Weiwei became increasingly active on the Internet. At the same time, he saw that his “enemies in the Chinese state grew surer that I was a threat.” There was no way they would countenance someone like him repeatedly poking fingers in their eyes in such a public and unrepentant way.

When the Wenchuan earthquake hit Sichuan Province in 2008, Ai Weiwei attacked the shoddy “bean curd” construction of the collapsed schools and buildings in which thousands of children died, as well as the corrupt officials who had allowed them to go up. His incendiary digital attacks and then a documentary film, Little Girl’s Cheeks, about those who’d died led to repeated altercations with police, including one in which he was beaten so badly that he needed brain surgery. For his exhibition “Remembering,” which opened in 2009 in Munich, he hung nine thousand children’s backpacks on the façade of the Haus der Kunst that spelled out in Chinese, “She lived happily in this world for seven years.” By then he’d concluded that it was necessary to “say goodbye to autocracy, no matter what form it takes and no matter how it’s justified, because the result is always the same: denial of equality, perversion of justice, warping of happiness.”

Then his blog was shut down. He wrote that it was becoming clear that “there was no further space for negotiation with the Chinese government.” Summoned by the police for “a cup of tea (被喝茶)”—a euphemism for being politically warned—his response was predictable: “Reject cynicism, reject cooperation, refuse to be intimidated, refuse to ‘drink tea.’” He counterattacked against the party’s practice of “intimidating you and weakening your resistance” until you censor yourself. “If everyone spoke,” he observes, “this society would have transformed itself long ago.”

In November 2010 he joined a group of artists protesting the seizure of their homes by local officials, and marched with them into Tiananmen Square. “If in a pitch-dark room I find a single candle, I will light that candle,” he defiantly proclaimed. “I have no choice. No matter how the government tried to shut me down, I would always seek to make my voice heard.” Then, to prevent him from attending the opening of his new studio in Shanghai, he was put under house arrest and the studio was bulldozed. Then they put his Beijing compound under around-the-clock police surveillance.

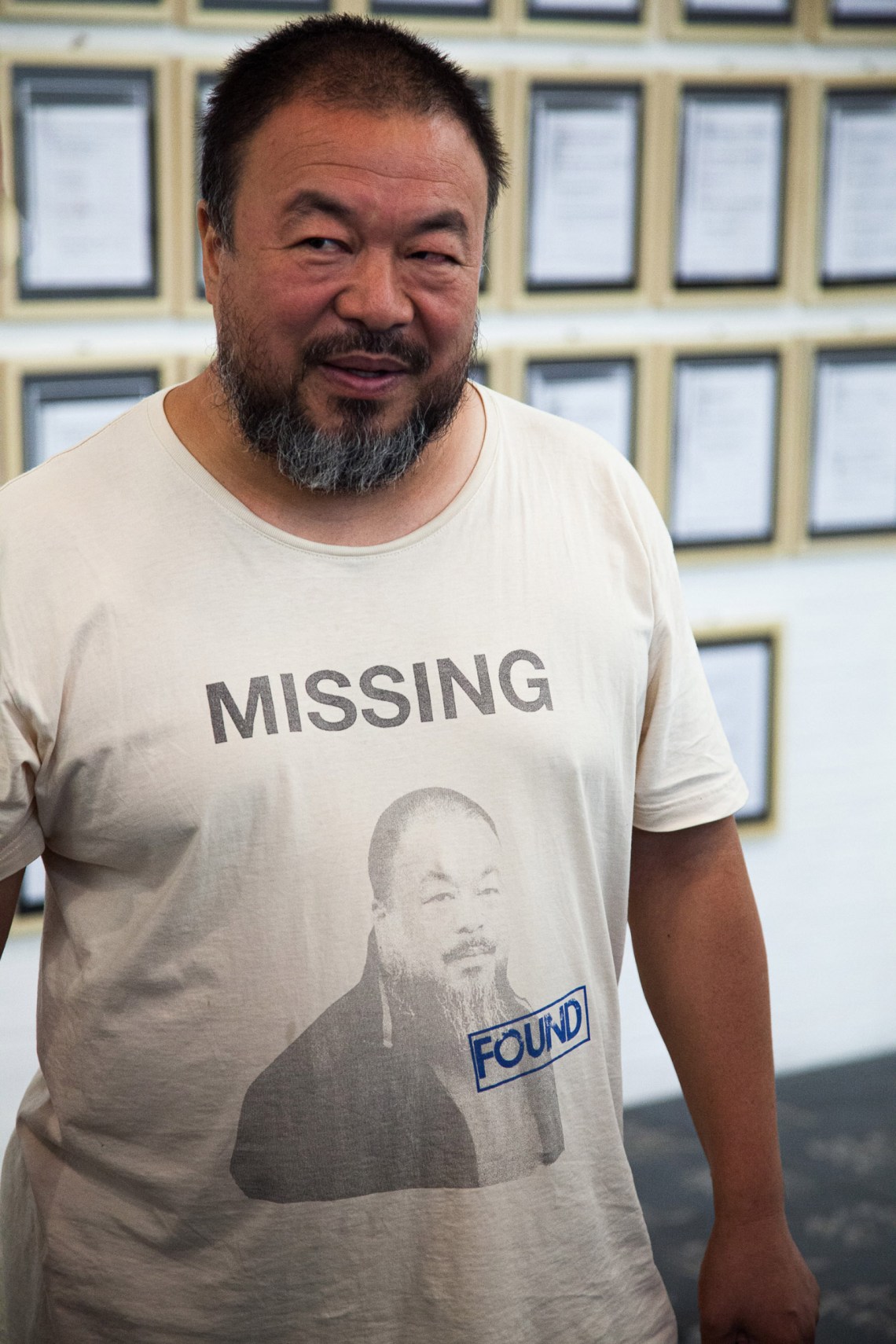

I met Ai Weiwei for the first time in Beijing with Orville Schell in September 2011, soon after he was released from prison. He was open and relaxed, with no evident signs of his incarceration except for his T-shirt, which bore his portrait and the words “MISSING” and “FOUND” stamped above and below.

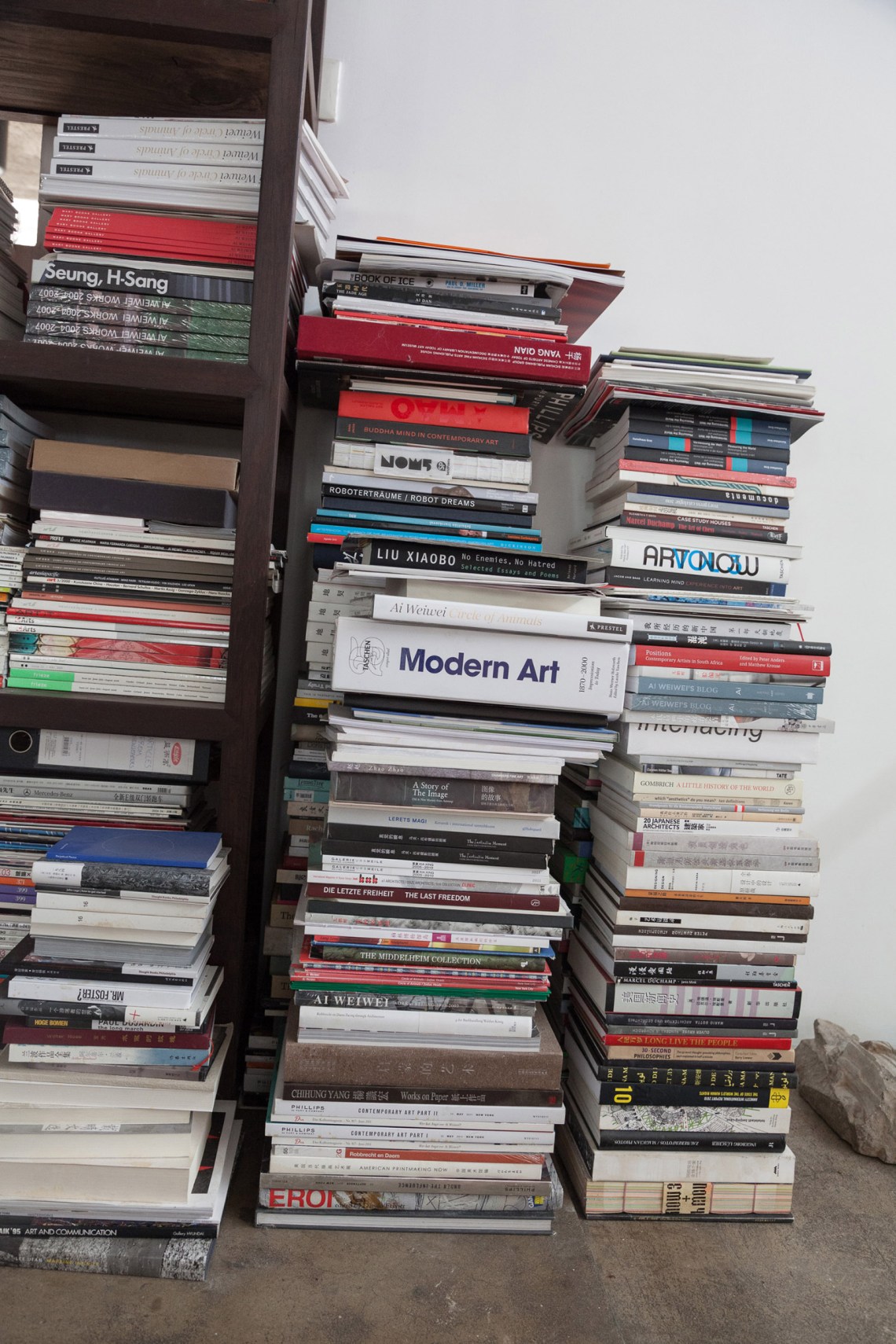

Our meeting led to a follow-up visit at his Beijing studio in February 2012. We sat and talked at the long table that’s in one of my photos, and at a certain point he saw my camera and suggested I might like to wander around the studio with it on my own. He said something like “feel free.” His irony wasn’t lost on me. The government was monitoring him 24/7—and I thought it likely that it was monitoring me as well. As I wandered, it felt like a freighted moment…but who knew?

This selection is drawn from more than 220 previously unpublished photographs of Ai Weiwei’s studio. They captured a moment not long before China’s best-known artist was forced into exile. The studio remains as it was—frozen in time.

—Clifford Ross

“I thought of my father, and began to understand what protracted suffering he must have endured, for in a Communist system, to be constantly under observation is the normal state of existence,” he writes.

To someone with an independent streak, this incessant surveillance means that life itself is like a term of penal servitude. In my case, as time went on, the intrusions afflicted me with a nameless exhaustion, as though some unidentifiable foreign body had been planted inside me.

Ai Weiwei’s blunt language and defiant actions were so offensive to the party that in 2011 he was detained as he tried to board a flight for Taipei. After being handcuffed and hooded, he was driven to a remote prison and held under an extrajudicial detention provision—called “residential surveillance at a designated location (指定居 所监视居住)”—that allows the state to hold someone for six months without charges. “I had been kidnapped by the state,” he writes with his usual candor.

While in detention, he was interrogated daily, threatened with myriad but ever-changing charges, endlessly pressured to confess, and monitored constantly by cameras as well as two guards who stood inside his cell twenty-four hours a day “like wooden statues.” Accused of exhibiting an “intolerable insolence,” he responded with yet more insolence. “Even if you threaten to drag me out now and shoot me, my position won’t change,” he told his captors. However, as the weeks wore on, “doubts crept in as I lay awake in the late hours—about how this all would end, and about the path that had led me here…. I didn’t need sympathy—what I needed was justice. But justice was nowhere to be seen.”

Eighty-one days later he was released on bail, for reasons that were “just as opaque as the reason for my detention.” He was ordered to stay in Beijing and not use the Internet or interact with the media. Out of deference to his mother, partner, and son, he remained silent for over a month. But “to me the loss of the freedom to express myself was itself tantamount to captivity,” and soon Ai Weiwei was tweeting about his prison experiences. Since the party almost always retaliates against criticism, he was charged with owing over 15 million yuan in unpaid taxes. His response was to post a proclamation about his tax problem online.

On the first day he received some five thousand contributions totaling over two million yuan. Supporters even began flying paper airplanes made of banknotes over the walls of his compound. Ultimately he not only received more funds than he needed, but later paid everyone back.

Then, as a mocking “gift” to the Public Security Bureau, he installed a surveillance camera system in his studio, recorded every aspect of his daily life, and streamed it online. He also sculpted a surveillance camera out of marble as satirical artwork. And in a final act of lèse-majesté, he constructed a replica of his prison cell complete with wax figures of himself and his guards as an art installation for museums around the world. “Any artwork, if it’s relevant, is political,” he chided. Otherwise it’s “just some kind of decoration, or for money making.”

Still, he could not but feel enervated at being in such a state of constant adversity. “Power, spreading its tentacles everywhere, revealed my vulnerability,” he writes. “But it was not directed solely at me—its attention was directed at every individual, for everyone has soft, hidden places that they don’t want others to touch.”

In China almost every dissident is forced to mix some measure of submission with their defiance in order to survive. But in Ai Weiwei’s case, his enfant terrible side was prevailing. He’d already concluded that “if you’re not prepared to make a name for yourself through resistance, the only way to win distinction is through bowing and scraping.” He adds, “I myself do not have it within me to compromise.”

When in 2015, four years after his release from prison, his passport was finally returned, Ai Weiwei was able to follow his partner and their young son to Berlin, where he’d established a studio. “A sense of belonging is central to one’s identity, for only with it can one find a spiritual refuge,” he wistfully notes. Nonetheless, “my father, my son, and I have all ended up on the same path, leaving the land where we were born.” Still he kept working. His show Trace, first displayed in 2014 in the old penitentiary on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, consisted of Lego portraits of 176 people from 33 countries who’d been imprisoned for speaking out. In 2010–2011 he brought 100 million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds (weighing ten tons) to Tate Modern in London for an exhibit calling attention to the mode of mass production now involved in the label “Made in China.”

Looking back on his experiences growing up with his father in labor camps, he writes of feeling regret about

the lack of empathy and understanding I showed when I was younger. During those long weeks in secret detention, my fear was not that I might not be able to see my son again, but that I might not have the chance to let him really know me.

Ai Weiwei’s memoir is an effort to fill this lacuna, to spell out who his father was and who he now is himself as a person and a father.

The life of the Ai family composes a drama whose every act brings ever more egregious assaults by the state against it. But whereas Ai Qing’s initial commitment to socialism made it difficult for him to ever fully turn against Mao’s revolution, his son, lacking that same idealism, slid more easily into opposition, cynicism, and then finally resistance. His “intolerable insolence” meant that Ai Weiwei was fated to be left with only two paths forward: either being crushed at home or fleeing into foreign exile. For as he warned, “When a state restricts a citizen’s movements, this means it becomes a prison.” And, he adds, “Never love a person or a country that you don’t have the freedom to leave.”

It does not take many pages of this memoir to leave one feeling drowned in toxic revolutionary brine. But even as readers will be repelled by the relentless savagery of China’s capricious revolution, they will be uplifted by this father-and-son story of humanism stubbornly asserted against it. Ai Weiwei reminds us that freedom is part of being human in the modern world: “Although China grows more powerful, its moral decay simply spreads anxiety and uncertainty in the world.”

How such an open, clear, and uncompromising voice as Ai Weiwei’s arose in such a closed and compromised society is a mystery. But Ai Weiwei’s defiance is the dialectical result of the party’s own unyielding and often destructive militancy. The tough, resolute critics to whom China has repeatedly given rise—such as the Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo, the Democracy Wall activist Wei Jingsheng, the dissident astrophysicist Fang Lizhi, and most recently the law professor Xu Zhangrun—were all forged on the anvil of the party’s own extremism. The way that Ai père et fils sought justice, truth, freedom, and liberty in the face of the party’s myriad oppressive attacks makes them of a kind. And Ai Weiwei’s steadfast devotion to free expression and resistance to the Chinese Communist Party’s unrelenting pressures makes this book glow as if irradiated with righteousness.