Given the global influence of the rap, breakdancing, graffiti, and DJ culture that flowered in the South Bronx in the 1970s and 1980s, one might guess that a work of scholarship about that place and time would focus on hip-hop. Bronx-born Peter L’Official, a literature professor at Bard, acknowledges that “hip-hop was, and is, the Bronx’s social novel for the ages”—and that Tricia Rose, Greg Tate, Jeff Chang, and others have already covered that ground. In his recent book, Urban Legends: The South Bronx in Representation and Ruin, he deliberately and skillfully reads the borough instead through novels, movies, art, journalism, and municipal records, looking to both unpack and undo its mythology. The result is a vibrant cultural history that gestures beyond the tropes of the boogie down and the burning metropolis, those pervasive narratives of cultural renaissance and urban neglect that have dogged the area for half a century.

As its name makes plain, the South Bronx lies in the southern part of the Bronx, the northernmost of New York City’s five boroughs. On the subway map, the South Bronx extends from the head and neck of northern Manhattan like an elephant ear, separated by the Harlem River. Its borders have been debated over the years, but its many neighborhoods include Concourse, Mott Haven, Melrose, and Port Morris. The 6 train gets you there from Midtown, as Jonathan Kozol points out in his urban classic Amazing Grace (1995), making “nine stops in the 18-minute ride between East 59th Street and Brook Avenue. When you enter the train, you are in the seventh richest congressional district in the nation. When you leave, you are in the poorest.” That district would be the Fifteenth—the country’s poorest, still.

It wasn’t always so. The area was once Lenape territory, and then beginning in the seventeenth century it was taken over by colonial farmland, owned by the aristocratic Morris family, which included Founding Fathers Lewis Morris (who signed the Declaration of Independence) and Gouverneur Morris (who signed the Constitution). Annexed by New York City by 1895 and connected by subway to Manhattan in 1904, the Bronx grew into a polyglot boomtown and manufacturing hub that became known for making pianos, and offered a step up for families escaping the crowded tenements of the Lower East Side, or Fascist Italy, or Nazi Germany.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, working-class German, Italian, Irish, and especially Jewish immigrants had started populating the area. By the 1930s, social workers dubbed it the “Jewish Borough.” According to the Bronx-born writer and activist Grace Paley, the Great Depression “was the first great blow to the unfinished Bronx,” and with disinvestment, its already aging housing stock went into further decline. After World War II, the South Bronx experienced a second boom, beginning with Puerto Ricans and also Blacks from the South. But as they arrived, New York City was deindustrializing. Racist redlining policies prevented housing reinvestment as whites took flight.

Between 1950 and 1960 the population of the South Bronx went from being two thirds non-Hispanic white to two thirds Black and Puerto Rican. Its northern boundary changed, too, extending to the Cross Bronx Expressway, completed in 1963 as part of Robert Moses’s plan for renewing the city.The Cross Bronx Expressway dealt the Bronx its second big blow. In the introduction to his Bitter Bronx: Thirteen Stories (2015), Bronxite Jerome Charyn describes its construction as an injury tantamount to urbicide, displacing local businesses and thousands of residents, decreasing property values, increasing vacancy rates, and helping to turn the Bronx into “the poorest, most crowded barrio east of Mississippi,” plowing right through it “like the avenue’s own sore rib.”

Things went from bad to worse in the 1960s, as is well documented by Jill Jonnes in South Bronx Rising: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of an American City (2002). Then, during the economic stagnation of the 1970s, unemployment rose—and with it crime and the fear of crime. Cue more white flight. Vacant buildings couldn’t be sold. Squatters moved in. Gangs and drugs beset the community. The city was nearly bankrupt. Landlords were pushed to convert their emptying buildings to Section 8 housing, which paid them federal rental assistance to take in low-income tenants. The rates were so pitifully low that without a profit, these landlords lost the incentive to maintain their buildings. Budget cuts meant building inspectors and fire marshals stopped checking for violations. Banks and insurance companies further redlined the area.

“Absentee slumlords” and “welfare hotels” became the new terms of abuse. Unable to sell, landlords faced mortgage default. Into this grim picture stepped a shady character called “the fixer” with the following scheme: buy a building below cost; sell it over and over on paper using shell companies; drive up the value a little with each sale; take out a fraudulent insurance policy; strip the overvalued property of its wiring, plumbing, and fixtures for salvage; and then—for the payoff—burn it to the ground. Some local residents set fires, too, encouraged by policies granting priority status for new housing in potentially safer neighborhoods to Section 8 tenants who were burned out of their apartments. Block after block of the once-flourishing province of working- and middle-class family life was destroyed, discarded, demolished. The teeming, populous Bronx had morphed into a dreadful object lesson.

Advertisement

By 1977, when L’Official’s book begins, so many buildings there were burning each day that the fire department could not, or would not, keep up. The Bronx lost more than 108,000 residential units between 1970 and 1981 to abandonment, demolition, or arson—a fifth of its housing stock and a full third of the estimated housing units lost in New York City. That decade, over 40 percent of the South Bronx was abandoned or destroyed. But put another way, almost 60 percent of it was not.

In Urban Legends L’Official examines the South Bronx as both a real place and a repository of myth, much as the historian Alan Trachtenberg wrote about the Brooklyn Bridge as “fact and symbol.” How is it, L’Official asks, that this pocket of New York City came to symbolize slumdom all over the world, when its problems—poverty, unemployment, municipal disinvestment, racism, and building deterioration—could be found in any other American city suffering the fallout of a deindustrializing economy?

In his 1964 essay “Harlem Is Nowhere,” Ralph Ellison wrote, “To live in Harlem is to dwell in the very bowels of the city,” with “its crimes, its casual violence, its crumbling buildings…and vermin-invaded rooms.” Yet no other urban locale in the nation registers decline in the public psyche so persistently as the South Bronx—not the Harlem Ellison described as symbolizing “the Negro’s perpetual alienation in the land of his birth,” not Trenton, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Chicago’s South Side, or South Central LA. Apart from the Gaza Strip, I’m hard pressed to name another hot spot that warns the outsider quite so successfully to beware.

I thought frequently of Helga Tawil-Souri and Dina Matar’s anthology Gaza as Metaphor (2016) while reading Urban Legends. Both books look closely at how imperiled places are pathologized in the public imagination. Just as Gaza has become the archetype of an “open-air prison,” evoking metaphors of terror, siege, occupation, resistance, and humanitarian disaster, the Bronx brings to mind “urban ruin,” synonymous with crime, civic neglect, and the failings of “inner cities” (created by white flight, redlining, and other urban planning) and the communities of color that call those places home. The media has depicted both as unruly funeral pyres, but where Gaza is seen as the ravaged stand-in for the Palestinians’ perennial conflict with the State of Israel, the South Bronx was long characterized as urbanism’s nadir, the wreckage of the “underclass”—Reaganite code for the “undeserving” Black and brown poor.

“C’est Le Bronx” was French parlance in the 1980s for “It’s a mess,” just as during the Lebanese civil war, “C’est pas Beyrouth” signified “It’s not a disaster.” Nowadays you can buy a “C’est Le Bronx” T-shirt for twenty-eight dollars from the locally operated merchandiser From the Bronx, which claims, from a place of pride, rebranding the borough as its mission.

Rebranding and rehabilitation aside, the Bronx’s bad rep persists. When my friend Eneida Cardona got mugged on Philly’s Cherokee Street in the mid-2000s, she defended herself against the assailants who mistook her for white by identifying herself as a Puerto Rican girl from the Bronx, which was Nuyorican code for Don’t mess with me, pendejos, you picked the wrong mark.

I read L’Official’s book with interest, having recently moved with my family, at the height of the pandemic, from a three-room apartment in Upper Manhattan to a single-family house in the northwest Bronx. The move was a sign of our upward mobility, but I’m sorry to say that there were plenty of people in our circle who wondered if it was safe.

L’Official explains how two events in October 1977 helped create the story of the South Bronx as a neighborhood gone to hell, and why the story stuck. The first was a nationally televised visit by President Jimmy Carter, who toured the vacant lots, heaps of rubble, and burned-out buildings along a stretch of Charlotte Street—once a flourishing neighborhood of more than three thousand people—at the behest of his Housing and Urban Development secretary, Patricia Harris, the first Black woman to serve in a US cabinet. Whereas the Nixon administration had shifted money away from urban areas like the South Bronx, accelerating their decline, Harris urged reinvestment, advocating for the right of people “to have urban life as a real choice—not only the option of the rich or the fate of the poor.”

Advertisement

The South Bronx was chosen strategically. After years of landlords abandoning their buildings instead of repairing them, and letting them be destroyed by fires, the area’s dereliction represented the failings of late-stage capitalism, almost cinematically so. (Indeed, it was long favored by film scouts looking to suggest dystopia, and by politicians as the bleakest location on whistle-stop tours of urban America.) Narrating footage of Carter’s walk on the evening news, the journalist Bob Schieffer called the South Bronx “the worst slum in America”—a phrase that quickly became commonplace and has sometimes been attributed to Carter himself. Never mind that the view looked different just a few blocks over, where community organizers were successfully rehabilitating housing.

The second event took place a week after Carter’s photo op. During a live broadcast of game 2 of the 1977 World Series, played between the Yankees and the Dodgers, an aerial camera panned from Yankee Stadium to a nearby blaze. An abandoned school building was on fire. “There it is, ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning,” Howard Cosell supposedly said—and many people still attribute these words to him, even though it has been established for quite some time that he never spoke them, nor did anyone else during the broadcast. The phrase actually comes from a 1972 documentary, The Bronx Is Burning, about the fire epidemic. By the time of Carter’s visit and the World Series, L’Official observes, all of this was too easily conflated:

Images of the Bronx as a burning borough had already been singed onto the public retina…. What was, and what was willed into being were often—as Cosell’s phantom quote illustrates—indistinguishable.

L’Official describes these two events as urban legends owing to the way their partial and distorted views solidified over time. The fire outside the ballpark was real. The TV audience could see the smoke. But the quote that became famous was apocryphal. Destroyed Charlotte Street was as real as bombed-out Warsaw, London, or Berlin, but it was a four- to six-block area of a much bigger borough, a place where—as in those European cities—people still lived, loved, worked, parented, and prayed. In showing us how fixed these two legends became, L’Official aims to loosen their dehumanizing hold.

Throughout Urban Legends, L’Official urges us to consider how we look at, think of, and talk about the South Bronx—and, by extension, other places like it:

I encourage us to think about concepts like the “inner city,” “blight,” the “ghetto,” “wasteland,” and “no-man’s-land”—metaphorical constructions of place that continue, to this day, to be used to characterize cities and, more pointedly, the people in them—as versions of urban legends as well. These are all euphemisms, ways to describe a city so that people don’t have to think any deeper about why it looks the way that it does, a shorthand for describing problems so complex, systems of oppression so entrenched, that the realization of their uncomfortable proximity produces a kind of willful distancing via language. They are coded special signifiers for race.

He argues that while gothic portrayals of the South Bronx in fiction and film obliterated the lived reality of the area’s residents in the 1970s and 1980s, the same ruins that inspired harmful stereotypes also inspired literary and artistic depictions of decay. Through his examination of these depictions, he dissects the mythology projected onto the borough, showing the harm it’s done.

For example, shortly after President Carter’s tour, a New York Times editorial proclaimed that visiting the South Bronx was “as crucial to the understanding of American urban life as a visit to Auschwitz is to understanding Nazism,” whereupon chartered bus tours of Europeans actually began stopping at Charlotte Street to take in the ruins, en route to the Bronx Zoo, just as they might, on a tour of Italy, make a stop at Pompeii. In Don DeLillo’s novel Underworld (1997), a tour bus with a sign reading “South Bronx Surreal” and carrying about thirty Europeans pulls up across the street from a derelict tenement building, watched by two local nuns. As the tourists exit the bus to gawk at the boarded-up buildings, toting cameras, one of the nuns shouts at them, “It’s not surreal. It’s real, it’s real. Your bus is surreal. You’re surreal.”

L’Official notes that as late as 2013, a company called Real Bronx Tours offered visitors “a ride through a real New York City ‘GHETTO,’” promising walks through “a ‘pickpocket’ park” and views of folks in line at a food pantry. Local public outcry and a scathing open letter by the Bronx borough president, Ruben Diaz Jr., eventually forced the tour to cease operation.

Whereas L’Official credits DeLillo’s rendering of the South Bronx in Underworld for grappling with the socioeconomic processes that drove the area to ruin, he takes Tom Wolfe to task for failing to capture the effects of systemic racism, suburbanization, deindustrialization, and white flight in his best-selling satirical novel of race and class, The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987). Told at a reporter’s remove, the book resorts to caricature in its paranoid concern with facades. A disquietingly grotesque portrayal of the South Bronx emerges as Manhattan’s bestial Other—echoing the era’s journalism and ultimately failing to illuminate the real life within Bronx neighborhoods that, according to L’Official’s persuasive and excoriating reading, remain in Wolfe’s writing both overdetermined and inscrutable.

L’Official contrasts the sprawling social novels of DeLillo and Wolfe with the more personal fiction of Abraham Rodriguez, a South Bronx native, in his story collection The Boy Without a Flag: Tales of the South Bronx (1992) and its follow-up, the novel Spidertown (1993). Rodriguez’s unsentimental portraits of life among the ruins invert the understanding of such spaces as merely hostile, barren, and threatening. The story “No More War Games,” which follows kids hanging out in an empty lot next to abandoned buildings, is a meditation on violence, but also on innocence and play, happiness and exploration.

I wish that more of Urban Legends focused on how South Bronx residents have represented themselves—instead, the views imposed by folks who never lived there dominate the book. L’Official surmises that there’s not much literary fiction about Black and Latinx life by writers from the South Bronx—in contrast to nearby Harlem and Washington Heights—because its creative energy found expression instead in the populist literature of hip-hop, the poetry of graffiti (whose practitioners called themselves writers), and the social novels of rap, perhaps most recognizably expressed in “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five:

Broken glass everywhere

People pissing on the stairs, you know they just don’t care

I can’t take the smell, can’t take the noise

Got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice

Rats in the front room, roaches in the back

Junkies in the alley with a baseball bat

I tried to get away, but I couldn’t get far

’Cuz a man with a tow truck repossessed my car

According to L’Official, “The Message” can be read “as urban reportage, as an example of lyric and poetic dexterity, and certainly as a work of literary and musical protest—in other words, as poetry or sociology, fields in which academic discourse has often invoked hip-hop.” And so he mostly leaves hip-hop out of his own account. But the problem with eliding such rich source material in a cultural study of the South Bronx is that while so much of what’s told from the inside is sophisticated sociology, so much of what’s told from the outside is stereotypical caca.

Take, for example, Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981)—a police drama about the Forty-First Precinct, directed by Daniel Petrie and starring Paul Newman, which portrays the Bronx as a lost cause. It opens barbarically, with the blaxploitation icon Pam Grier as a drug-addled street hustler inexplicably shooting two NYPD patrolmen point blank in a parked squad car, then disappearing over a pile of rubble in a field of trash, whereupon scavengers, mostly children, sneak like wild animals from nearby abandoned buildings to strip the dead cops of their valuables. Entirely absent is any care or interest in why the scene looks like this or who these people are, apart from the benevolent white savior cop played by Newman. To his credit, L’Official balances the considerable space he allots to analyzing this movie with an account of the Black and Puerto Rican locals who organized to protest its dehumanizing portrayal of their home.

The strongest chapters of Urban Legends are the ones devoted to visual representations of the South Bronx. L’Official innovatively pairs—and assesses on an equal plane—what he deems “municipal art” and “high art” as a means of studying the city’s built environment, and as an intervention against predominant stereotypical narratives about the place. As part of this discussion, he compares the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s trompe l’oeil “Occupied Look” program—which began in the early 1980s under Mayor Ed Koch and consisted of vinyl decals painted to look like curtains, shades, shutters, or window panes on boarded-up windows—with the work a decade earlier of the artist Gordon Matta-Clark, whose Bronx Floors (1972–1973) presented sculptural slabs of floor that he sliced from abandoned buildings in the South Bronx.

L’Official describes Matta-Clark as “a kind of archivist who, with ramshackle precision, extracted samples of rapidly deteriorating sections of the city as both testament to and protest against the prevailing urban condition.” He also quotes Robert Jacobson, director of the Bronx office of the City Planning Commission, on the purpose of the Occupied Look decals: “The image that the Bronx projects—and projects to potential investors—is the image you see from that expressway, and our goal is to soften that image so people will be willing to invest.” With his examination of these undertakings as well as fascinating images from what he refers to as the municipal “shadow archives,” L’Official proves himself to be an original kind of archivist, and the book really sings.

As an amateur photographer myself—interested in documenting the ripped advertisements on New York City subway platforms, which can resemble abstract paintings and are sometimes described as “unintentional art”—I especially enjoyed the care L’Official took in examining the “shadow archive.” These include photographs from the Department of Finance’s citywide census, made between 1983 and 1988, wherein officials collected over 800,000 images, about 85,000 of which show buildings and vacant lots in the Bronx. He discusses these alongside documentary photographs of the same period by Jerome Liebling, Ray Mortenson, and other photographers from the fine arts world, and asks an important question: “Where does the visual memory of a city reside?”

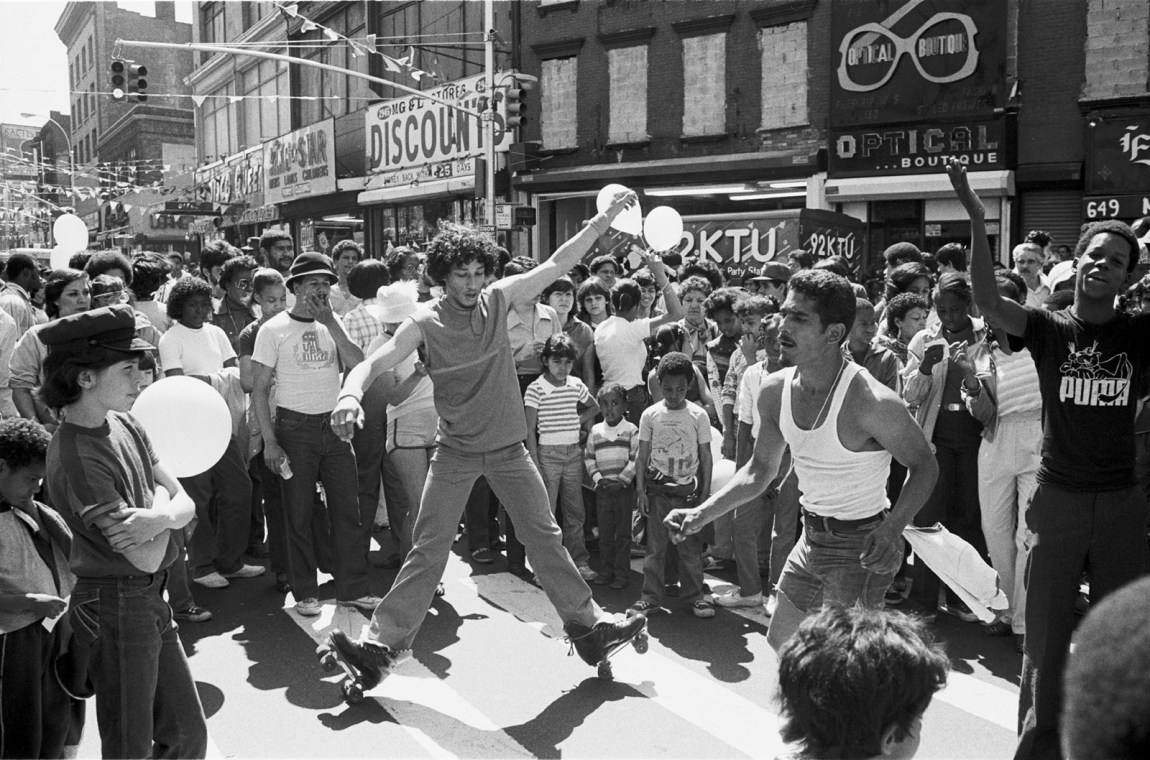

L’Official argues that the municipality’s aim for total representation of New York City’s blocks and lots (which preceded projects like Google’s Street View) resulted in an archive that prevents the South Bronx from passing entirely into myth. That’s because in many of the building census photos, there are people—hanging out, crossing the street, shaking hands. These are the everyday people who lived there, not the boogeymen from Fort Apache, the Bronx. Even the unpeopled tax photos, like the one of 1305 Nelson Avenue, which shows a massive pile of rubble, when paired with more self-consciously haunting images of abandoned, fire-ravaged buildings by Liebling and Mortenson, make us feel more keenly that the space was once occupied.

Mortenson was familiar with the work of Matta-Clark and was employed as an electrician when he first started shooting the South Bronx in the early 1980s. His mantra on the subway he took to get there was “Take the 5, stay alive. Take the 4, dead for sure,” because the neighborhoods along the 5 train seemed to offer fewer chances of getting mugged or stumbling across a drug deal. His photographs convey the breadth of destruction in Mott Haven, Morrisania, and Tremont by offering us a way to glimpse the community’s inner life. In one such intimate shot, Untitled (19 October 1983), an old, upholstered wingback armchair sits covered in a blizzard of fallen paint flakes before a wall on which, above two crossed swords, is written in Arabic: “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah.” The chair is lit like a throne from which someone has recently risen.

In Liebling’s monumental composition Orlando Building, South Bronx, New York City (1977), it appears that the photographer has stepped into the empty lot to get the low-angled shot of the bare brick facade of a building thrusting upward from a hill of rubble (see illustration at beginning of article). Liebling, who had been a member of the Photo League, was interested in documenting urban destruction but not in celebrating ruin. His pictures sought to reveal the community in a seemingly inhospitable place by representing the environment, and sometimes its people, stripped down to its essence. His straightforward presentation of structure and form shares a precisionist ethic with the anonymous tax photographs, illuminating a series of local disasters in the Bronx, the aftereffects of rupture worth scrutiny and redress as opposed to revulsion, sick fascination, or scorn.

Liebling’s South Bronx series, supported by a Guggenheim fellowship, made visual parallels with images of urban destruction from postwar Warsaw, Rotterdam, London, and Berlin by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Werner Bischof, and others. This was not Pompeii, though it looked as much like a warzone as Dresden did after the firebombs. These images and the dozens of others that L’Official reproduces in the book are less spectacular than familiar depictions of the Bronx as a no-man’s-land, including the broadcast of President Carter’s visit. They testify to the lives of its mostly Black and Latinx residents, whether pictured in the frame or, more often, just outside it. This targeted landscape was their home.

Though Urban Legends focuses on words and pictures rather than music, I couldn’t help hearing “The Message” as its soundtrack. With its kaleidoscopic way of seeing place, L’Official’s book operates something like the video artist and cinematographer Arthur Jafa’s work, including his seven-minute video essay Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death, which suggests how visual media can transmit beauty and alienation as powerfully as can Black music. It also shares something with Lucy Sante’s portraits of New York City, Low Life (1991) and Evidence (1992), although where Sante admits to being drawn to Surrealism—“I commuted to high school in Manhattan and would sometimes cut class, wander down the West Side through what was still a very industrial area of New York, looking for the dream landscapes of Rimbaud and Lautréamont”—L’Official’s attitude to Surrealism is to put a pin in it.

With grief rather than nostalgia, L’Official mentions that Community Board 5, made up of the University Heights and Fordham neighborhoods of the Bronx, where he grew up, now faces the biggest threat of displacement by gentrification in New York City, signaled by a pair of twenty-five-story luxury towers that he watched rise from his living-room window while he finished writing his book. Real estate developers have in recent years attempted to attract money by renaming neighborhoods in the South Bronx with sobriquets like “SoBro” and “the Piano District.” Walking through Port Morris or Mott Haven now, you’ll find art galleries, subway-tiled cafés serving espresso, and locally owned stores selling Bronx-branded merchandise.

As for Charlotte Street, it was converted from an “urban jungle” to a pocket of ninety-two subsidized ranch houses called Charlotte Gardens, the first of which went on the market in 1983. In his conclusion L’Official writes:

The South Bronx waterfront, once entirely industrial, will soon appear as nearly indistinguishable from the newly built-up shorelines of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, or Long Island City and Astoria, Queens, all of which now feature packed enclaves of steel- and glass-clad residential towers.

Given this rapid growth, he asks, how will this place live on in our memory? One way may be the Universal Hip Hop Museum, founded by Rocky Bucano and backed by rappers Kurtis Blow, Afrika Bambaataa, Grandmaster Melle Mel, Nas, Ice-T, LL Cool J, and others, which plans to open a physical space in the South Bronx next year, and an immersive app through which you can access 3D objects and performances starting this spring.

We hear much in Urban Legends about what the South Bronx wasn’t. It wasn’t merely a backdrop for political initiatives, a sideshow, a theater of poverty, a crime den, a metaphor, a wasteland. Yet it can be hard to see the Bronx as it actually is. L’Official’s book predates the pandemic, which has had a devastating effect on the area. According to a June 2021 report by the Office of the New York State Comptroller, it was struck harder than any other borough, suffering the city’s highest rates of hospitalization and death, precisely because it already suffered the highest rates of food insecurity, poverty, unemployment, and lack of access to health care. “In the period leading up to the arrival of Covid-19 in New York City, the Bronx saw improvement across numerous socioeconomic indicators, including population, employment, and wage growth,” the comptroller’s report said. “The pandemic put an abrupt stop to that trajectory.” Gentrification notwithstanding, that’s how it is now.

This Issue

April 7, 2022

The Last of Her Kind

The Futility of Censorship