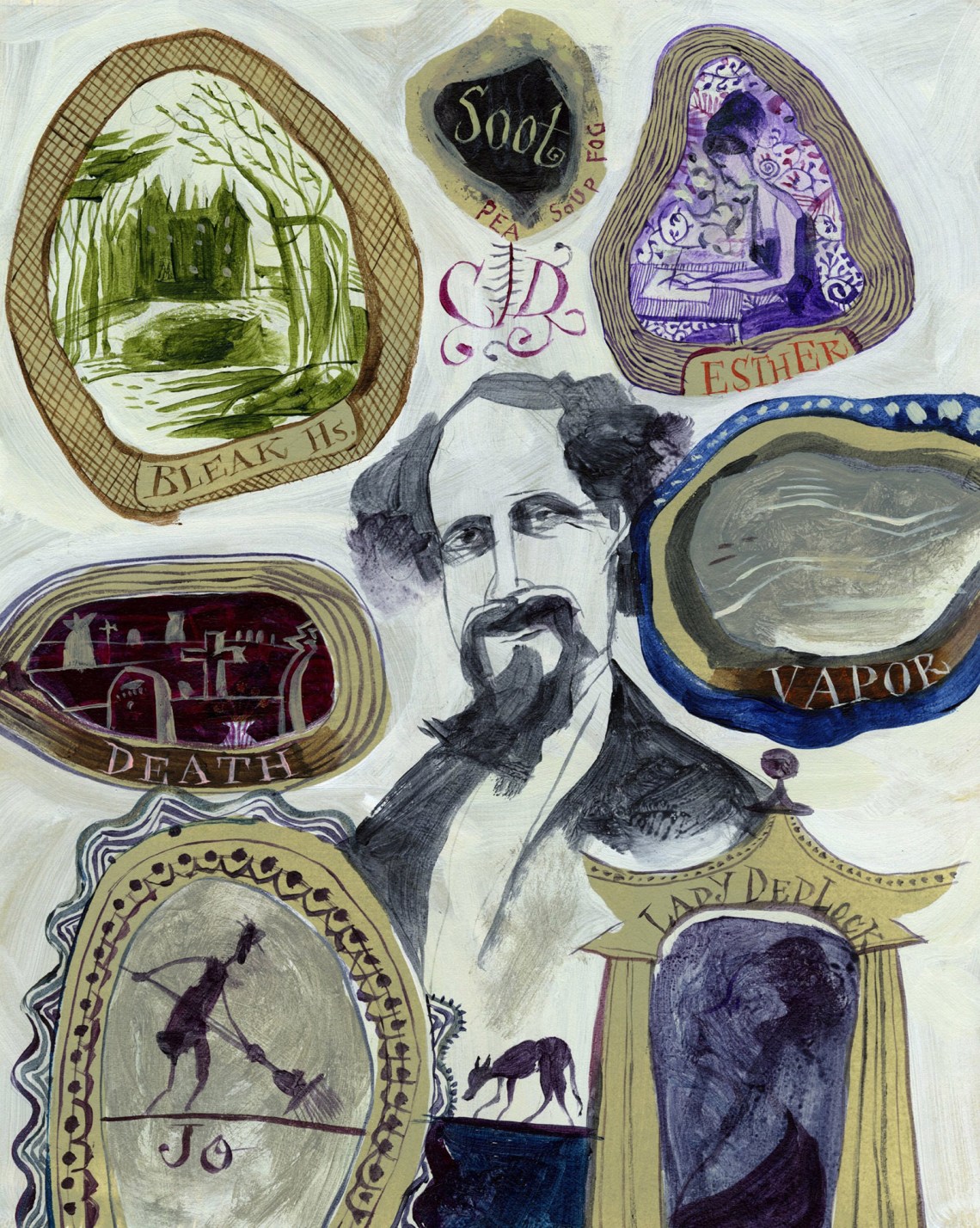

I never tire of its nine hundred pages, of reading it, teaching it, talking about it. “London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather,” with the streets full of the horse droppings that the Victorians euphemistically called mud, and the chimney smoke perpetually “lowering down,” as if the city were snowing soot. Those are the opening sentences of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1852–1853); read them aloud and try to stop yourself from going on. “Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers,” and pedestrians slipping and sliding around them as the shit in the streets goes on “accumulating at compound interest.”

“Fog everywhere. Fog up the river,” and down it too, flowing and rolling and creeping, and in speaking those lines your voice turns foghorn, with the word booming out onomatopoeically. Fog. It gets into your throat, it makes you wheeze, and it pinches your toes. So Dickens says, on this day when the sun seems to have died, and the haggard glow of gaslight can barely brighten the mist. Mist? No, nor fog either, really. It’s what we now call smog, that’s the real London particular, a greenish-gray pea soup; smoke and fog together, the deadly combination of river vapors and soft coal.

Only the novel’s own eerie light can pierce it, with a voice as implacable as the weather itself; a voice like that of an unforgiving God. Dickens loads his prose with gerunds, a series of ongoing unfinished actions; he writes in the present tense and no single sentence in these opening paragraphs is grammatically complete. Fragments only, though with subordinate clauses and prepositional phrases. Everything moves but nothing goes anywhere, a furious stasis in which the novel’s very language suggests the interminable lawsuit on which its plot depends. But finally he gives us a verb, at the start of the fourth paragraph: “The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest….” Is. These things are, this city is what it is, and woe to anyone who might hope to change it.

Except for Dickens himself. He won’t let go of that prosecutorial voice, but after two relentless chapters he switches out of it and into a register that is in every way its opposite. “I have a great deal of difficulty in beginning to write my portion of these pages”: so we read at the start of chapter 3, halfway through the first of the novel’s twenty monthly serial installments. Those words belong to a young woman named Esther Summerson, who speaks to us in the first person and the past tense, and the rest of the book will alternate between her voice and the brooding third-person, present-tense narration of its opening pages.

Dickens isn’t usually celebrated for his technical innovations, but Bleak House is one of the greatest examples of successful experimentation in the language. His earlier novels had at times used the present tense for local effect, a way to ratchet up a sense of immediacy, but neither he nor anyone else had ever before relied on it so fully. And then there’s the fact that the narrative is split, multivoiced in a way that’s familiar to us now because Dickens made it so: split into two equal and competing parts, with neither of them framing or controlling the other. The book begins in one voice and it ends in Esther’s, but they never fuse; their dialectic finds no synthesis. Nor will Esther ever appear in those imperious third-person chapters, and we’re not told just how she knows that her tale is but a “portion of these pages.” In that one line she seems more aware of the book’s other narrator than he—inevitably he—ever is of her, but part of the genius of Bleak House lies in its refusal to provide answers, its willingness to let the smoke blow through its own cracks and fissures. Esther tells us that her mind quickens when her affection is engaged, as it is by everyone around her, and she stands for her creator as an exemplum of kindness and love. But not even she can make the world that Bleak House gives us seem whole.

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst teaches English literature at Oxford and is the author of Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist (2011), in which he traced the first years of the writer’s career, from his initial sketches in journals now remembered only because he wrote for them to the publication of Oliver Twist (1837–1839). Dickens had just turned twenty-seven when that novel ended its serial run, but he didn’t need its success to make him famous. The loosely crocheted comedy of The Pickwick Papers (1836–1837) had already done that, and for a while Dickens was at work on both books at once, switching between them in order to produce his monthly chunk of each. It all happened with a terrible speed, and Becoming Dickens itself has something thrilling about it. It’s an origin story, in which we watch the hero discover his vocation and his powers—powers that had reached their peak in 1851, the year that Douglas-Fairhurst identifies as “the turning point.”

Advertisement

That year ended with the start of Dickens’s work on Bleak House. Its first monthly part appeared in March 1852, and it was indeed a turning point in his career, a moment when his ambitions seemed to leap. He was never just an entertainer, but he was also the only one of the great Victorians to publish all his novels in serial form. His early books had often seemed improvised, their incidents invented against a deadline, and at times the whole suffered from the sheer vivacity of its separate pieces. Dickens only started to make detailed preparatory notes with Dombey and Son (1846–1848), defining his plot and his characters in advance, and working out how to distribute the novel’s events across the thirty-two pages of its regular monthly parts.

But Bleak House did something more. In writing it Dickens found a language, a set of totalizing metaphors and images—the fog, the courts—that allowed him to pull an apparently disparate set of characters together into a picture of his society as a whole. It was the darkest book he had yet written, as well as the most closely wrought, and it set a pattern for the rest of his career: a model for the similarly encyclopedic Little Dorrit (1855–1857) and Our Mutual Friend (1864–1865), the one controlled by the image of a debtors’ prison and the other by the flow of the Thames itself.

Still, a better title for Douglas-Fairhurst’s new book might play off his old one: Being Dickens. That is really what it’s about. There’s little here about the writing of Bleak House, and the hours the novelist spent with a pen in his hand are essentially irrecoverable. He said almost nothing in his letters about the new book in the months before he began it, and little more once he had, though in May 1852 he did write to a friend that its fourth installment was “rather a stunner”; the hyperbole is characteristic of the man who called himself the “Inimitable.”

The novel’s composition went smoothly, and Dickens met most of his deadlines without difficulty, pressed only by an installment that included a murder; in places his revisions make the manuscript almost illegible, but he was never at a loss for what should come next. Yet we do know that he tried to finish each installment in just two to three weeks of hard work, which left the rest of the month for the business—the performance—of being himself. That’s where Douglas-Fairhurst really excels, and why 1851 is such a good year for him to have chosen. It’s not only smack in the middle of both the writer’s career and the century itself; it’s also a year in which Dickens wrote very little fiction at all, when his entire life seems to have been spent in public.

How did the novelist pass his days? When did he get up, what did he eat for breakfast, and how long did he stay at his desk? What, above all, was it like to be him? Dickens always had secrets, but at this point most of them lay back in his childhood, when his jovial, improvident father landed in debtors’ prison and the twelve-year-old boy had to go to work, sticking labels on jars of shoe polish. Almost nobody knew about that, for Dickens hid his private self behind a tremendous charisma. He was a superb actor and a skilled amateur magician, and he had so much nervous energy that at times he needed to walk himself stupid by marching fifteen or twenty miles through the night.

His life is thoroughly documented, and The Turning Point rests on a generously acknowledged substratum of documentary research, above all on the twelve-volume Pilgrim Edition of his surviving letters.1 We know the facts—bacon every morning, and at his desk from ten until two—but Douglas-Fairhurst admits that trying to pin him down is “like grabbing hold of a handful of smoke.” Dickens once compared a swollen body he saw in the Paris morgue to a heap of “over-ripe figs.” Where did that image come from? How did he invent it? His prose is so grotesque and yet so comic, so consistently surprising, that I find his inner life impossible to imagine. He’s rarely subtle, and yet the quirks and contours of his imagination make Henry James look simple.

Advertisement

“So much of what a life includes inevitably falls between the cracks,” no matter how much we know, and in consequence Douglas-Fairhurst has decided to imagine “a different kind of biography,” not a chronology but a portrait of a particular man at a particular time. In this The Turning Point differs from the two major Dickens biographies of the past twenty years. Michael Slater assembled the definitive edition of his journalism, and then drew on his own unrivaled knowledge of primary sources to present a scholarly life of the working writer.2 It’s utterly reliable, but a bit of a dry crust, more consulted than read. Claire Tomalin’s version is characteristically vivid and brisk; it gets the man but says little about the work.3 Neither is completely satisfying, and probably the Dickens archive is by now too big to be adequately represented in a single volume.

The odd thing, then, is that the slice of experience Douglas-Fairhurst offers seems a workable compromise between the books of his immediate predecessors. Most biographies “speed up the events of their subjects’ lives…years pass in pages.” The Turning Point is in contrast an exercise in “slow biography.” It restricts its scope in order to give a minutely detailed account of a single but definitive moment, dropping the pace “until it returns to something closer to the texture of ordinary experience.”

Still, such a purposefully narrow study stands as a late stage in literary scholarship. It depends on the cradle-to-grave biographies from which it departs. The book that The Turning Point most recalls is James Shapiro’s A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599 (2005), always remembering that we know far more about the one writer than the other. Shapiro made up for the gaps in our knowledge by telling us not only about Shakespeare’s plays but also about everything else that was happening in England that year, from the winter weather to yet another invasion of Ireland. Douglas-Fairhurst’s book tries something similar, but in places falls short. It succeeds with an account of the Great Exhibition of 1851, the first of the World’s Fairs, held in a magnificent greenhouse—a “Crystal Palace”—erected in Hyde Park. Dickens was ambivalent about it, but the show’s bouncing confident belief in Progress still consumed his interest. Yet Douglas-Fairhurst doesn’t fully earn his subtitle, and his narrative has more than a few loose ends, bits of news that he never quite makes relevant. One of them is an account of a new book that was published in England in 1851, under the title The Whale. Melville’s Moby-Dick was indeed published that year, but at the time it made virtually no impression on Dickens or anyone else.

Dickens did two big things in the year before his turning point. One was finishing the semi-autobiographical David Copperfield (1849–1850), which he later described as his “favourite child” among all his books. The other was starting a weekly magazine called Household Words. The novel has left a bigger memory, but in its time the magazine was the more important. He had always wanted a voice and an influence beyond his fiction alone, and it gave him a chance to speak directly about the issues that mattered to him, to touch on what he described as “all social evils, and all home affections and associations.” He took half the magazine’s profits, along with a generous salary and payment for his own contributions on top of that. But the only capital Dickens put into the project was his talent. Its risks were borne by his regular publishers, the firm of Bradbury and Evans, who wanted to keep their star happy and had the capacity to make it work. For they were printers as well as publishers. They owned their own presses, as other houses did not, and could save by using them; they had a distribution network, and they also knew how to advertise.

Household Words sold for two pence, with a weekly circulation of about 38,000 copies, and within a few weeks was firmly in the black. The magazine ran some notable fiction, including Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1854–1855), along with humorous sketches and crusading pieces on subjects like city sanitation and the gap between rich and poor. Its articles were published anonymously, though Dickens himself wrote a fair portion of its twenty-four double-columned pages, and imposed his own voice and vision upon the rest. Many of its pieces were devoted to showing how the different pieces of Victorian society worked—the post office, say, or a candle factory, or London’s newly professionalized police force. In one essay the novelist followed one of the city’s first detectives at night as he worked his way through some of its worst slums; it was wet and the streetlights were blurred by the rain, “as if we saw them through tears.”

Household Words was an immediate success, and Douglas-Fairhurst begins Dickens’s year with it. It is January 25, 1851, a warmish winter Saturday, and though the novelist has a “stinking cold” he nevertheless decides, as he steps through “his bright green front door,” to walk the two miles from his house to the magazine’s offices in Wellington Street, between Covent Garden and the Strand. He was living then, with his wife and nine children, in a house just south of Regent’s Park, and there were several routes he could take.

But for Douglas-Fairhurst the particular path doesn’t matter as much as the fact that, no matter which way he went, the novelist would have walked through streets and scenes that he had already described in his fiction. “London was becoming Dickensian,” Douglas-Fairhurst writes, and that conceit allows him to take a panoptic view of the city: its theaters and street musicians, the “bill-stickers” who slapped advertising posters on “every square foot of external space,” the urban renewal that had driven new streets through some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods without providing anywhere for their displaced inhabitants to go. He touches on the other writers with whom Dickens shared the metropolis: the bombastic Thomas Carlyle and a young woman from the provinces who would soon call herself George Eliot. Then the novelist reaches his office, and The Turning Point introduces us to the men he worked with.

There’s a good bit of biographical sleight of hand going on here. Douglas-Fairhurst uses a seasonal calendar to organize his narrative—winter to spring and on to winter again, to a December in which the novelist is fully engaged by his new book. The result is a skillfully cast illusion of dailiness, in which time passes and yet also stands still, with the seasons providing a narrative spine on which Douglas-Fairhurst can hang essayistic accounts of Dickens’s characteristic interests and pastimes. Some of them were professional, Household Words above all, and there was his growing anger at England’s sclerotic legal system, in which a civil suit might languish for decades. A few Chancery cases went on until the estate at issue was entirely consumed by court costs, as happens with the fictional Jarndyce v. Jarndyce in Bleak House.

Some of Dickens’s interests were philanthropic, yet the energy he threw into them amounted to a full-time job. He helped administer Urania Cottage, a halfway house for “fallen women,” prostitutes, and petty thieves who wanted to change their lives. He ran an amateur theatrical company, in whose expensively mounted productions other writers often took roles. In 1851 he used it to raise money for indigent authors, putting on a show at the London house of the Duke of Devonshire, an elderly bachelor who was delighted to meet one of his favorite novelists. Some of these concerns and activities can be pegged to particular dates: a letter that spring, for example, about a young woman who wouldn’t accept the cottage’s rules. But most of them were ongoing, and Douglas-Fairhurst has had to decide just where in his story to put them.

Many of the articles Dickens commissioned for Household Words left their impression on the new book. Some crucial scenes drew on a piece from April 1850 that described London’s cemeteries as so “closely-packed” with the dead that the disease-laden “exhalations of putrefaction always vitiate the air.” The following February another article presented the Thames as covered by a thick scum of sewage, dead dogs, and rotting vegetables. And one of Bleak House’s most memorable characters, the illiterate crossing sweeper Jo, had his origins in a bit of testimony recorded in the magazine’s monthly supplement; a crossing sweeper being a boy with a broom who, in hopes of a tip, would sweep the pedestrian’s path clean. Such a boy named George Ruby had been called to give evidence in an assault case and told the court that he didn’t know what prayers were, or God, though he had heard of the devil; the article used the boy’s ignorance to underline the moral cost of poverty.

Finding new biographical ground with a figure like Dickens is usually a matter of emphasis, and after reading Douglas-Fairhurst’s account of Household Words I’m convinced that the magazine was so utterly central to Dickens’s sense of himself that we wouldn’t have had any of his later and larger novels without it. The weekly was a great omnium-gatherum, and those books depend on what he learned as its editor, on his ever-growing sense of London’s, of England’s, sheer complexity. He couldn’t always make the different pieces fit together; no one could. But that’s what he spent the second half of his career—he died in 1870—trying to do.

Dickens first mentioned his new novel in a letter in February 1851, writing that he felt the initial “shadows of a new story hovering in a ghostly way about me.” It was months before he could begin, however, for he was consumed first by his theatricals and then by house hunting. The lease on his Regent’s Park house was up, and in the fall he moved his family to a larger and grander structure in Bloomsbury, supervising its furnishing and decoration with the obsessive skill of a professional, even as he began to feel the “wild necessity” to write. In November he told his publishers to advertise the novel’s first installment for March 1852, and when the book was finally done he wrote in its preface that he had never before had so many readers.

Bleak House is about inheritance. Other things too, but inheritance first, insofar as it begins with a quarrel over a will. A great Chancery lawsuit has locked up the money of four families at least, and also allowed a bit of London real estate to fall into ruin for lack of a responsible landlord—an area that’s now a slum called Tom-All-Alone’s. But money isn’t the only thing one can inherit. Esther Summerson is an illegitimate child. She lives under an alias and is told by an aunt that she has inherited her unknown mother’s shame. Later we learn that she has also gotten her mother’s beauty, the beauty of a woman who has schooled herself into a frightening hauteur and is now known as Lady Dedlock. Esther too is involved in the suit of Jarndyce v. Jarndyce, though she doesn’t yet know it, but early in the novel she meets a man named Gridley who has spent his entire adult life in Chancery’s coils. No one caught in Gridley’s suit wants it to proceed, but once begun it cannot be stopped. It’s driven him mad, and yet when he makes a personal appeal to the judge he is told that he “mustn’t look to individuals. It’s the system.” Right and wrong don’t matter, and no individual judge or lawyer is responsible; it’s the system, and the system, as Dickens would write in Little Dorrit, is nobody’s fault.

What is our burden of care, our separate share of the charge for the world we live in? What binds individuals to their society, and how can we make sense of the forces that link us all? Unsolvable questions, and inescapable ones: Dickens would ask them time and again, but never with quite the demonic force that he summoned in Bleak House. The moment comes in a chapter named for that awful slum, and in fact Dickens thought about using “Tom-All-Alone’s” as his title for the novel. But the chapter begins with “my Lady Dedlock” in motion from her country house in Lincolnshire to her “muffled and dreary” place in town, and it ends with Jo serving as guide to a mysteriously veiled woman. She wants to visit one of the foul urban cemeteries Household Words had crusaded against, and though she is dressed as a servant even Jo can tell from her walk that she’s not; her foot is too “unaccustomed” to the mud. The woman asks to see the grave of a newly dead opium addict, a man known only as “Nemo” (“no one” in Latin), and yet what can the proud Honoria Dedlock have to do with such a place and person? Or as Dickens writes, in one of the novel’s most famous passages:

What connexion can there be, between the place in Lincolnshire, the house in town, the [footman] in powder, and the whereabout of Jo the outlaw with the broom, who had that distant ray of light upon him when he swept the churchyard-step? What connexion can there have been between many people in the innumerable histories of this world, who, from opposite sides of great gulfs, have, nevertheless, been very curiously brought together!

Victorian social thought was perfectly capable of defining those connections, of tracing the forces that linked such different people and places. Engels did it, and Ruskin, and so in a more piecemeal way did the writers of Household Words. But Dickens was above all a novelist, a storyteller, and he had a different way of answering his own rhetorical questions.

I ask my students, when we get to this part of the novel, to look at the chapter titles. We visit that graveyard in “Tom-All-Alone’s” and then switch out of the third person and into what’s called “Esther’s Narrative,” a chapter followed in turn by one set in the country and named “Lady Dedlock.” What is the connection between that slum and “the place in Lincolnshire”? It’s the girl, it’s Esther—her own story is the link, and literally so, though neither mother nor daughter yet knows it and the reader is at best half aware. Dickens draws his connections in narrative terms, one bit of his tale leading on to the next, causes building to consequences. Jo catches a fever as he stands by that pestilential spot, and then wanders out into the countryside, a vagrant whom Esther discovers and tries to nurse back to health. Her resemblance to the woman in the churchyard startles him, and then she sickens in turn; and much will come of that too, as if those grave-borne lines of infection were as one with the twists of the plot.

There are other ways to understand the world, but that was Dickens’s; such narrative connections were how he made sense of society. He stitched one chapter sequentially to another, and in doing so he stepped across those “great gulfs” to show how we are all bound together. At times he took his readers to places they would rather not imagine; there were always some who preferred the relatively cozy comedy of Pickwick to the dark majesty of his later work. The Turning Point isn’t the last word on Bleak House, and I wish that Douglas-Fairhurst hadn’t limited himself to a single year, that he had followed the book’s story out to the writing of its last chapter. Dickens finished it only in August 1853, and appropriately enough in the offices of Household Words. But Douglas-Fairhurst’s learning is buttressed by something of Dickens’s own exuberance, and in any case there can never be a last word about such a novel. In fact Bleak House barely has a last word itself. It ends with an em dash, “even supposing—,” as though the serial novelist wanted us to wait for what’s next, as he shuts the door behind him.

-

1

The Letters of Charles Dickens, edited by Madeline House, Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and others (Oxford: Clarendon, 1965–2002). ↩

-

2

The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens’ Journalism, 4 volumes (Ohio State University Press, 1994–2000). ↩

-

3

Michael Slater, Charles Dickens (Yale University Press, 2009); Claire Tomalin, Charles Dickens: A Life (Penguin Press, 2011). ↩