If you’ve ever been curious about how America’s so-called deep state really works, these three memoirs are a good place to start. Their authors were, until recently, unknown to the public, having quietly risen to just below the surface of the American foreign policy establishment. None of them, it’s fair to say, would have written a memoir had they not been catapulted to national prominence as witnesses in Donald Trump’s first impeachment hearings in the fall of 2019.

Marie Yovanovitch ascended through the Foreign Service to a series of ambassadorships, including, fatefully, to Ukraine. Alexander S. Vindman rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the US Army, including combat experience in Iraq, before being appointed to the staff of the National Security Council (NSC). His first boss there was Fiona Hill, whose career included stints in academia (Harvard’s Kennedy School), think tanks (the Brookings Institution), and the intelligence services (the National Intelligence Council and the NSC). All three focused on Russia and other territories of the former Soviet Union. As civil servants in both Democratic and Republican administrations, they gave the deep state what it wanted: deep expertise, deep loyalty to American institutions, and fourteen-hour workdays.

That was not all. Modern bureaucracies, Max Weber wrote in Politik als Beruf (Politics as a Vocation, 1919),

have developed, in the interest of integrity, a high sense of collective honor, without which the danger of terrible corruption and a vulgar philistinism looms over us and threatens the purely technical functioning of the state apparatus.

We are not accustomed to thinking of bureaucrats as repositories of honor, a quality more readily associated with aristocrats. Weber, however, had a very particular form of honor in mind. “The honor of the civil servant,” he observed,

consists of the capacity to execute conscientiously the command of his superiors, precisely as if the command corresponded to his own conviction. This holds even if the order appears incorrect to him. Without this supreme moral discipline and self-denial, the whole apparatus would fall to pieces.

The problem in the Trump administration was that the commander in chief was himself the apotheosis of corruption and philistinism. What if his orders were not simply incorrect—that is, failed to properly align ends and means—but morally wrong or illegal?

Less than two years into his presidency, one high-ranking civil servant anonymously published an essay in The New York Times announcing that he and like-minded colleagues were “working diligently from within to frustrate parts of [Trump’s] agenda and his worst inclinations.” He justified this extraordinary stance by citing the president’s “amorality.” “Anyone who works with him,” the official declared, “knows he is not moored to any discernible first principles that guide his decision making.” Thwarting certain decisions by such a president was therefore not dishonorable, because those decisions were unprincipled. As the “adults in the room,” Anonymous and his fellow resisters were “trying to do what’s right even when Donald Trump won’t.”1 While Trump, understandably furious, embarked on a witch hunt for disloyal civil servants, the deep state functioned as the steady state. Notwithstanding Weber’s warning, the apparatus did not fall to pieces.

It will hardly come as news that Trump struck many of those who worked in his administration as poorly informed, incapable of sustained attention, narcissistic, and addicted to lying. Still, there are moments in these memoirs that make one’s hair stand on end all over again. According to Yovanovitch, at his first meeting with Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko, in 2017, Trump turned to his national security adviser, H. R. McMaster, to ask whether there were American troops in the breakaway Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. In November 2018, when Russian forces fired on and seized Ukrainian military vessels in international waters in the Black Sea, Trump fell into what Vindman describes as “decision paralysis,” unable to contemplate any course of action that might upset Vladimir Putin. His speaking style, even at closed-door meetings, struck Hill as “a word fog,” a “head-spinning, incoherent monologue…in which you stumbled around looking for meaning.”

Born in Canada to immigrant parents whose families had fled Bolshevik Russia, Yovanovitch inherited their sense of displacement. Throughout her childhood in Connecticut, where her parents worked as boarding school teachers, “I just wanted to fit in.” The title of her memoir, Lessons from the Edge, captures the feeling of liminality. It also alludes to the political hit job by Trump’s uncivil servant Rudolph Giuliani that brought Yovanovitch to the edge of professional ruin, as well as to the place where it happened: Ukraine means “at the edge” or “borderland.” It may even gesture toward Yovanovitch’s experience as a woman in the Foreign Service, which she joined in 1986, when the State Department’s upper ranks were still famously “pale, male, and Yale.” Lessons from the Edge portrays an American diplomatic corps just beginning to grapple with the implications of its relentless rhetoric of meritocracy, recapitulating earlier debates over the admission of women and access for ethnic and racial minorities to the Ivy League.

Advertisement

It helped, of course, that Yovanovitch was pale and Princeton. Despite or perhaps because of the everyday sexism at Foggy Bottom, she became an exemplar of the strict professional integrity described by Weber. In her words, she was “a committed rules-follower.” And this, it turned out, is what guided her work as ambassador to Kyrgyzstan (2005–2008), Armenia (2008–2011), and Ukraine (2016–2019): getting these former Soviet republics to follow rules. Rules barring nepotism and bribery, rules requiring transparency and genuine competition, rules against killing or poisoning or throwing acid in the faces of one’s political rivals. The rules, in other words, of democracy and regulated markets.

“I spent much of my time in the Foreign Service,” Yovanovitch notes, “trying to help reformers inside and outside government battle against the poor governance and corruption that were bleeding their countries.” In such cases, she argues, America’s values and interests are in sync: “Corrupt leaders are inherently untrustworthy as partners, and the loathing they engender at home almost inevitably leads to instability within—and sometimes beyond—their borders.” There are times, however, “when we have to balance our interests against our values, because the US has important priorities that often require dealing with unprincipled leaders who are stealing their country’s heritage.”

That last sentence takes for granted that the corrupt, rule-breaking leaders with whom America must sometimes deal—faute de mieux—are only to be found abroad. Indeed, the Foreign Service catechism of balancing American values and interests, in which Yovanovitch appears to be a fervent believer, is built on such an assumption. But what if a clash between American values and interests originates at home? The final third of Lessons from the Edge tracks Yovanovitch’s dawning realization that, as corrupt as Ukraine may have been (when she arrived in 2016, it ranked 131st out of 176 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, tied with Russia), the greatest threat to her effort to promote the rule of law in Kyiv came not from Ukrainian politicians and oligarchs, but from the White House.

It’s not that Trump wanted Ukraine to be corrupt; he seems not to have cared. What he did want, starting in 2018, was to tarnish the reputation of the person he correctly intuited was most likely to be the Democratic nominee for president in 2020, Joe Biden. As vice-president, Biden had periodically stepped in to enforce the State Department’s anticorruption efforts in Ukraine, at one point demanding the resignation of Ukraine’s supremely venal prosecutor general, Viktor Shokin, as a condition for an American loan guarantee. Biden’s relationship to corruption in Ukraine was more complicated than that, however. In 2014 the Ukrainian energy company Burisma Holdings, owned by the oligarch Mykola Zlochevsky, appointed Hunter Biden, the vice-president’s son, to its board of directors. Technically this may not qualify as nepotism, but it bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the Chinese practice of placing relatives of senior leaders (so-called princelings) in lucrative business relationships with foreign companies. It looked a lot like the corruption the United States was pressuring Ukraine to eliminate.

One of the central methods of disinformation is to turn the truth upside down. This has the advantage of producing assertions that have a toehold in the truth, because they draw on the same data but offer the opposite interpretation with maximally disorienting effects. Trump and Giuliani are masters of this dark art. Hence their claim that Biden had forced Shokin’s resignation because he was investigating corruption charges at Burisma Holdings that would have implicated Biden’s son. In truth, Shokin failed to investigate Burisma when there was ample reason to do so, just as he avoided investigating other corrupt Ukrainian companies. Hence their claim that Ukraine (not Russia) had attempted to manipulate the US election in 2016 in order to help Hillary Clinton (not Donald Trump). Hence the claim that Ambassador Yovanovitch had facilitated Kyiv’s covert effort to help Clinton win the election, that she had handed a “do not prosecute” list to Shokin’s successor as Ukraine’s prosecutor general in a continuing effort to protect Hunter Biden, and—for good measure—that she had embezzled US government funds intended to assist Ukraine.

The narrative of Yovanovitch as a rogue ambassador was not simply fictitious; it was the exact opposite of the truth. She was a relentless rule follower, a quality that did not endear her to those Ukrainian politicians and oligarchs who did not share her goal of promoting transparent governance of Ukraine’s state-owned companies. As her position became more untenable, Gordon Sondland, the real estate magnate whom Trump had appointed ambassador to the European Union after he donated $1 million to Trump’s inauguration committee, gave Yovanovitch some advice:

Advertisement

You know the president, and even if you don’t know the president personally, you know what he’s like and what he likes. Put out a tweet about how much you love the president…. You need to go big or go home.

The idea of pledging fealty to an individual struck Yovanovitch as “downright un-American. We had disposed of that idea in 1776.” She watched in anguish and disbelief as Giuliani, collaborating with Ukrainian politicians put off by her anticorruption efforts, conspired—with assistance from Fox News and the Hill journalist John Solomon—to trash her reputation. The ethos of nonpartisanship, or what Weber called “moral discipline and self-denial,” effectively inhibited civil servant Yovanovitch both from “going big” and from fighting back publicly. Even more troubling, the State Department, her employer for over three decades, declined to come to her defense. To be sure, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had pledged the “uncompromising personal and professional integrity” of the Foreign Service, vowing “unstinting respect in word and deed for my colleagues,” in contrast to the contempt that his predecessor, Rex Tillerson, had shown toward America’s diplomatic corps. In reality, however, Pompeo was content to let America’s persistent ambassador to Ukraine twist in the wind until the career-ending message arrived in April 2019: “The president has lost confidence in you.” Yovanovitch went home.

Giuliani had now delivered the first installment of what was intended to be a grand quid pro quo. He had rid Ukrainian politicians and oligarchs of an inconvenient American ambassador and thereby set the stage for them to deliver the desired payback: dirt on Joe Biden. Even as Trump was issuing thunderous denials that Russia had interfered on his behalf in the 2016 election, he and his henchmen were actively soliciting interference by Ukraine to help him win a second term in 2020. This quintessentially Trumpian “deal” climaxed with the now infamous July 25, 2019, phone call between the American president and his recently elected Ukrainian counterpart, Volodymyr Zelensky. Earlier that month, Trump had abruptly and without explanation put a hold on nearly $400 million in security assistance earmarked by Congress for Ukraine, including $250 million in military aid. During the call, Trump told Zelensky, “I would like you to do us a favor.” He then mentioned several favors, among them an investigation of the Bidens and their “horrible” activities in Ukraine. Trump also told Zelensky that “the former ambassador from the United States, the woman, was bad news” and, channeling his inner Don (the Mafia variety), “she’s going to go through some things.”

Among the White House personnel listening in on that phone call was Alexander Vindman. Born in Soviet Ukraine, he arrived in the United States, like Yovanovitch, as a toddler, brought by his widowed father to Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, aka “Little Odessa,” where signs and conversations in Russian (and Ukrainian) were everywhere. A self-confessed late bloomer, Vindman initially flunked out of college before finding his footing in the army, where he embarked on a career that took him to South Korea, Germany, and Iraq. In Fallujah, he was wounded by a roadside bomb and received the Purple Heart, among other honors. In 2008 he became a foreign area officer, serving as military attaché in the US embassies in Kyiv and Moscow.

Vindman’s memoir, Here, Right Matters, reads like a cross between a bildungsroman and The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. It brims with hard-earned maxims: Don’t just start over; keep starting over. Be alert to both the absence of the normal and the presence of the abnormal. Trust your gut. Don’t self-deter. These are lessons Vindman learned in the army, but they became life lessons too. Like Yovanovitch, he developed a deep loyalty to the institution through which he served his adoptive country—and to that institution’s rules. Like the Foreign Service, the US military prides itself on being nonpartisan, an ethos heightened by the imperative of subordinating the armed forces to civilian authority. A politically partisan military might well cause the apparatus of governance to fall to pieces.

On July 25, when Trump asked Zelensky to investigate Joe Biden, Vindman knew that what he had just heard was “certainly awful and possibly unlawful.” He was all too familiar with people asking for these kinds of “favors” in places like Russia and Ukraine. Did other White House staff react similarly to Trump’s words? One of them, the senior attorney at the NSC, John Eisenberg, subsequently warned Vindman “not to tell anyone else about what the president had said on the call.” But that’s precisely what he did, reporting it to the NSC’s chief ethics counsel, who happened to be his twin brother, Eugene Vindman. “If what I just heard becomes public,” Alexander Vindman told his brother, “the president will be impeached.”

When I asked Vindman a year later (well before his memoir was published) to recount to my students at Penn how he had arrived at the momentous decision to report misconduct by the president of the United States, his answer was disarmingly simple: he just followed the rules. In the army, if a commanding officer issues an order that you suspect is illegal, you have not just the right but the duty to report it. As Vindman elaborates in Here, Right Matters:

The duty to report misconduct is a critical component of US Army leadership, as well as of the oath I’d taken to support and defend the US Constitution. Despite the president’s constitutional role as commander in chief, the head of the military that I had spent decades serving—in fact, because of his role—I had an obligation to report what he’d done.

Nobody else in the room, he surmised, “was going to do anything about it.”

In his book Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970), the social scientist Albert O. Hirschman offered a taxonomy of behaviors by disaffected citizens, consumers, and members of organizations. What drives some people to quit (by emigrating, buying goods elsewhere, or resigning) and others to speak out (in street protests, to the manager, to their employer)? How do feelings of loyalty complicate the decision to exit or speak out—or remain silent? Remarkably, Vindman appears to have experienced no inner struggle between his loyalty to his adoptive country and speaking out against its leader. Rules were rules. Within minutes of the telephone conversation between Trump and Zelensky, he relayed his concern to the office of the chief ethics counsel. It helped that army regulations mandated not just when to speak out, but how: not to the press, not on social media, but in-house, up the chain of command. Which is precisely what Vindman did.

It took six weeks for what he heard to become public, thanks to an anonymous whistleblower at the CIA who sent a damning memo to the inspector general of the intelligence community, Michael Atkinson, who was then forced by a congressional subpoena to share it with the House Intelligence Committee. Vindman’s memoir sheds light neither on the identity of the whistleblower nor on the manner by which the content of the July 25 phone call reached him or her. Vindman also does not indicate what he would have done had the charge of presidential misconduct not gone public. There was ample reason to suspect that his in-house reporting of Trump’s solicitation of foreign interference was going nowhere. To begin with, the transcript of the conversation prepared by the White House (the phone call itself was not recorded) omitted several crucial moments, and when Vindman, drawing on his own notes from the call, attempted to insert them, he was rebuffed. Even more alarming, Eisenberg had arranged to store the transcript not on the usual server but on a special server dedicated to covert operations and other highly sensitive data, with tightly restricted access even within the NSC.

It cannot be said, therefore, that the army’s procedures for reporting misconduct by a commanding officer worked. What can be said is that Vindman followed those procedures to the letter, and that it took extraordinary courage to do so. But perhaps not only courage. A recurring motif in Here, Right Matters is the realization—first by others, then gradually by Vindman himself—that his fervent patriotism, loyalty, and devotion to rules were accompanied, and perhaps in part enabled, by a certain political naiveté. A senior military figure had warned him, before he took up the position at the NSC, “This will be the most dangerous and challenging environment you’ve ever worked in. Including combat assignments.”

By his own admission, Vindman—“an infantry officer, not a political animal”—found the minefields in Washington, D.C., perhaps “harder to read and respond to” than those in Fallujah. It does not diminish his supreme moral discipline and self-denial (to borrow Weber’s terms again) to note that he appears to have been clueless about the likely repercussions of reporting Trump’s behind-the-scenes malfeasance. Others who witnessed Trump’s misconduct—and there was plenty to witness, from the 2016 election campaign to January 6, 2021—but who were mindful of their future careers remained silent.

Like the State Department during the smear campaign against Yovanovitch, the army remained silent when Vindman began to be pilloried by Republicans as anti-Trump, un-American (was he not an immigrant?), or perhaps a tool of Ukrainian intelligence operatives. When the White House blocked his scheduled promotion to the rank of colonel (a significant advancement in the army’s hierarchy) and later fired him and his brother from the NSC, only retired military officers spoke out in his defense. It is unclear what combination of desire to remain apart from the political fray along with personal and institutional self-preservation was at work. As one retired army officer and military historian (who wished to remain anonymous) told me, “The military will not be open about this case as long as Donald Trump is alive.”

Among those who sensed a certain naiveté in Vindman was the person who hired him at the NSC, Fiona Hill. The coauthor of a penetrating book on Vladimir Putin,2 Hill is a prominent analyst of Russian affairs known for savvy judgment and independence of mind. If the word “here” in the title of Vindman’s memoir proudly refers to the United States, in Hill’s There Is Nothing for You Here it refers, devastatingly, to the North of England, where she grew up as the daughter of a coal miner and a midwife. In her telling, the pervasive poverty, unemployment, and hopelessness of the North not only shaped her childhood (“There’s nothing for you here” is what her father told her when she graduated from high school) but go a long way toward explaining today’s right-wing populism, and not only in the United Kingdom.

Hill’s book straddles, not entirely successfully, the genres of memoir and policy paper. The autobiographical elements are vivid: She describes growing up with no car, no telephone, no idea what it means to own a house or for a parent to have a career as opposed to a job. Her school suffered from rampant vandalism; kids who did well on tests got beaten up. A disastrous interview for admission to Oxford highlighted the barriers faced by working-class students with the wrong accents and the wrong clothes. Supportive parents and mentors, however, along with an all-important scholarship to St. Andrews, began to open up new possibilities, including a study-abroad year in Moscow in 1987. For the first time in her life, Hill stopped dreading being asked where she was from and what her father did: Russians appreciated that she came from a world-famous coal-mining area and that her father was a miner. After Moscow came graduate training at Harvard, then positions in Washington think tanks and eventually in the US government.

Like Yovanovitch, Hill candidly describes what it’s like to be a woman in the foreign policy establishment: the pervasive sexism, lower salaries, and impostor syndrome. (Along with most male memoirists, Vindman does not mention what it’s like to be a man.) One of her early encounters with Trump was in connection with a phone call between the American and Russian presidents. Hill was the only Russian speaker among the advisers listening in on the conversation, and when it was over, she wanted to call attention to some subtly menacing aspects of Putin’s remarks that the simul-translation had missed. Trump, mistaking her for a secretary, requested that she type a copy of the press release describing how friendly Putin was and what a good call it had been. Hill froze, speechless, only to hear Trump bark, “Hey, darlin’, are you listening? Are you paying attention?” Soon, though, no one was mistaking her for a secretary, because Trump’s chief of staff, Reince Priebus, gave her a new, unofficial title (unbeknownst to Hill): “the Russia bitch.”

To be fair, Trump treated the entire National Security Council like a secretary. “He thought we all carried out basic administrative functions,” Hill notes.

Coming into government from his personally branded family enterprise and the world of reality television, where he was the one and only, exclusive boss who set his own agenda, the whole concept of an autonomous advisory body was entirely alien to him. Why did he even need this? He’d got this far in business and in politics by following his own instincts. He knew everything he needed to know.

This is not how the deep state likes to be treated. Presidents do not always follow the advice of experts employed by their administration, nor could they, insofar as different experts often give conflicting advice. But not paying attention to the advice of experts undermines the basis of their collective honor. It destroys the implicit contract between the deep state of expertise and the visible state of governance, according to which the first delivers the fruits of its labor and the second consumes those fruits rather than letting them rot.

Sexism and denigration of expertise notwithstanding, Hill regards herself as a refugee from the British class system. “The United States gave me opportunities,” she writes, “that I would never have had in the United Kingdom,” while noting that in America, race performs many of the same subtly exclusionary functions as class and accent in Great Britain. In fact, the leitmotif of There Is Nothing for You Here is the postindustrial polarization that she sees plaguing not just the US and the UK but Russia as well. Hill is unusual in that she has combined a sharply critical assessment of Putin and Russian foreign policy (long predating the Kremlin’s latest assault on Ukraine) with the conviction that post-Soviet Russia’s social and economic problems are fundamentally similar to those of the United States and Great Britain. All three countries substantially dismantled their welfare states in the final decades of the twentieth century. In all three, she sees the resulting rise in inequality, narrowing of social mobility, and extreme concentration of opportunity in large urban centers eroding the foundations of democracy. “Unless we figure out a way to solve [these problems],” she warns, “Russia’s fate and its slide into authoritarianism since 2000 could well be our own.”

Hill’s comparative analysis of socioeconomic malaise, and the warning that accompanies it, should be taken seriously. But her interest seems to lie exclusively (and repetitively) in cherry-picked similarities among the three countries. Comparative analysis is also supposed to reveal contrasts. It’s true that America, Great Britain, and post-Soviet Russia all scaled back their welfare systems in the name of promoting capitalism (under the banner of deregulation, free markets, small government, privatization, and/or shock therapy). But Russia’s economy, society, and politics profoundly differed from those of the US and the UK before as well as after that process played out. Russians are not so much politically polarized, like Brits and Americans, as politically anemic.

Even more important, the manner in which economic and social discontent translates into political shifts (whether toward authoritarianism or in other directions) is significantly different in Russia, where there are no visible alternatives to Putin—credible candidates having been exiled, jailed, or killed—and no genuinely competitive political parties, apart from the Communist Party. Trump, Putin, and Boris Johnson may share a charismatic ability to tap populist grievances, along with a my-country-first approach to international relations, but the way Putin came to power, consolidated power, and has exercised power for over two decades suggests that the Russian state, with no institutional checks and balances to speak of, belongs to a different breed.

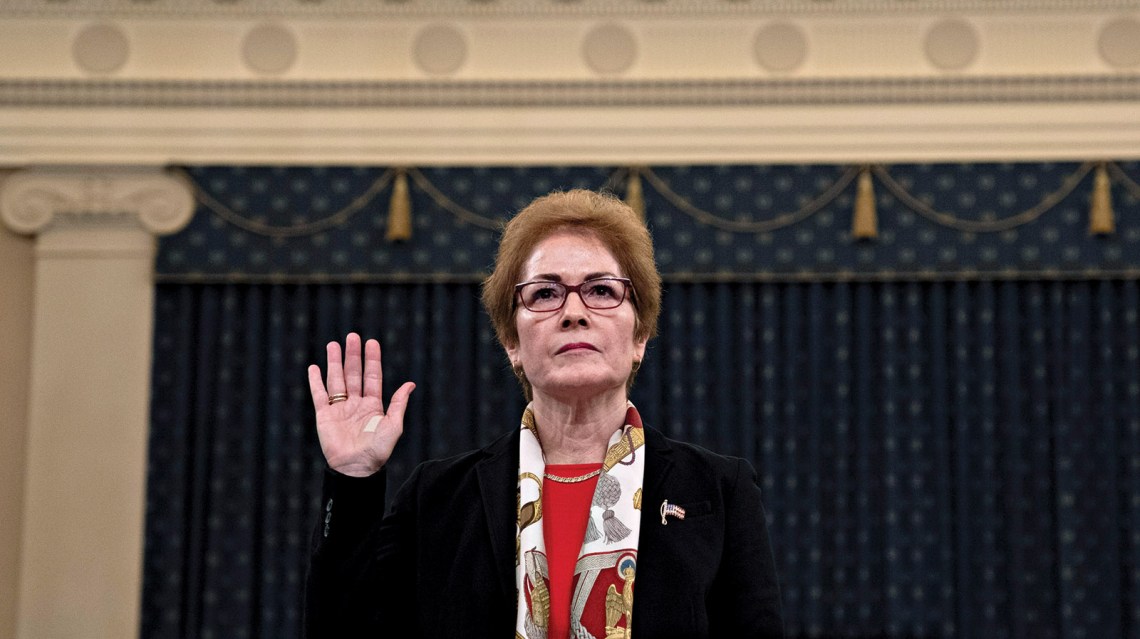

When Congress held impeachment hearings in fall 2019, Trump administration officials subpoenaed by the House Intelligence Committee came under enormous pressure not to comply. The State Department sought to keep Yovanovitch from testifying; the army did the same to Vindman. They courageously defied the pressure, affirming Congress’s rightful authority in the face of noncompliance by the executive branch. Hill, back at Brookings after resigning from her job at the NSC on July 15 (ten days before the Trump-Zelensky phone call), faced no such pressure from her employer. The American public was treated to the extraordinary spectacle of three valiant immigrants offering clear-eyed and damning evidence of misconduct by the American president.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that these Americans by choice, as Yovanovitch puts it, harbored a deeper devotion than many of their native-born colleagues—including John Eisenberg and John Bolton—to American ideals and to the moral discipline that Weber deemed essential for effective government. Did their testimony help discredit Donald Trump and thereby contribute to his defeat in November 2020? That is difficult to assess. But it unquestionably led to the reversal of his self-serving hold on assistance to Ukraine, the geopolitical significance of which is now clear to all.

This Issue

April 21, 2022

The Act of Persuasion

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Pianist

-

1

Anonymous, “I Am Part of the Resistance Inside the Trump Administration,” The New York Times, September 5, 2018. The author was subsequently revealed to be Miles Taylor, the chief of staff for the Department of Homeland Security. ↩

-

2

Fiona Hill and Clifford G. Gaddy, Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin (new and expanded edition, Brookings Institution, 2015). ↩