Con artists are having a moment. The latest crop features Elizabeth Holmes, the deep-voiced, unblinking leader of the fraudulent blood-testing start-up Theranos, one of many cheats now starring in books, podcasts, and dramatic television serials, as if they had accomplished something.

Perhaps they have. Like Gatsby, Holmes invented her celebrity and fortune out of virtually nothing: a smile, a wide and worshipful gaze, and genealogy. A Cincinnati hospital had been named for her great-great-grandfather, a doctor who married into the Fleischmann yeast fortune. One of Holmes’s earliest investors, initially dubious of a young woman who dropped out of college after a year, was impressed by her family history of success in business and medicine, apparently believing such expertise was magically transferrable across generations.

Genealogy, it turns out, has played a rich subterranean part in building improbable expectations, according to Francesca Morgan’s recent book, A Nation of Descendants: Politics and the Practice of Genealogy in US History. Probing the origins of American genealogy, she finds that, from our earliest years, it has been inflating our most grandiose fantasies. While it has served for some peoples—notably African Americans—as a means of recovering their history, finding a sense of belonging, and expanding the country’s social acceptance of once-despised minorities, it has acted at the same time as a tool of exclusion, promoting white supremacy, the Lost Cause, and eugenics. She quotes one “despairing professional” lamenting that “P.T. Barnum missed his calling when he neglected to become a genealogist.”

Yet despite our long fascination with family history, outsiders have also picked up on an American ambivalence toward it. Alexis de Tocqueville, as Morgan notes, was initially charmed by our democratic equality, with families emerging “constantly out of nothing, while others constantly fall back into nothing.” The longer he observed us, however, the more he was struck by the fact that, even while repudiating rank and class, the average American was “secretly distressed” about his position in society. Every other yahoo, or so it appeared, yearned to establish a connection to “the first settlers of the colonies,” whose descendants seemed to the French aristocrat suspiciously thick on the ground.

In the United States, genealogy became a means of constructing a narrative around identity, elevating oneself from the rabble by finding links to whatever passed for royalty in the blank void of the New World: prominent early colonists, soldiers who fought in the Revolution, the Founding Fathers. Not that aristocracy was forgotten. John Bernard Burke, whose Burke’s Peerage, founded by his father in 1826, became the great European guide to inbreeding, profited off the pre–Civil War vogue for heraldry among Americans willing to pay to prove a connection to the finer English families (no other nationality had the requisite cachet), preferably those with crests, which, though legally meaningless in this country, could be displayed “on their walls, on bookplates and other similar items of property, or in jewelry or cufflinks on their person.” Even superficial relatedness was prized. Morgan quotes Emerson ravished by “the fair complexion, blue eyes and open and florid aspects” of the English face. Elsewhere, the Sage of Concord sighed with regret over the lower order of laborers: “German & Irish nations, like the Negro, have a deal of guano in their destiny.” Such notions of hereditary greatness, beloved by eugenicists, congealed into the pseudoscientific foundation of white Christian supremacy.

It was during the Gilded Age, as American society became increasingly status-conscious and stratified, that genealogy experienced its first explosive rise. “Genealogy…joined manners, dress, foodways, and home furnishings in the toolboxes of Americans who wished to rise in society,” Morgan writes. Hereditary organizations were founded, often by and for women, largely white women (with a few important exceptions), a movement that eventually contributed to the rise of women’s social and political clubs generally. Morgan quotes a letter from a Boston genealogist describing a female client in Wahpeton, North Dakota, who was, as so many were, “anxious for a Mayflower.” The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), founded in 1890, was typical of such groups, allowing women barred from most professions to hold meetings, study history, and attain research skills that were potentially marketable. Although the Sons of the Revolution (SAR) was founded first, in 1889, the appeal to women was such that soon Daughters of the Revolution and Colonial Dames of America “far outnumbered Sons.”

A preponderance of women in the field gave rise, Morgan writes, to the stock character of the “chatty old lady,” the grandmother or spinster aunt who devoted her spare time and emotional energies to the collection and organization of family lore, sometimes dubbed “memory work” or “kin work.” As soon as family trees were seen as a form of female embroidery, kin work was derided as “unmanly,” encouraging a split between serious academic studies and genealogy, which was often based not on textual documentation but on names written in family Bibles, oral history, or stories passed down for generations. Thus genealogy became history’s redheaded—and relentlessly feminized—stepchild.

Advertisement

It also became a favorite device of white supremacists. “Hereditary organizations and the institutions that served them, such as libraries and historical societies,” Morgan argues, “expanded whiteness and Americanism” in a host of ways. She describes the practice by the DAR and other groups of installing plaques on boulders or walls preserving the names and birthdates of the first white babies born in a given locale, a weird corollary to the Confederate monuments that sprang up in the early years of the twentieth century.

During an era when Teddy Roosevelt and other nationalists feared that white Anglo-Saxons, whose birth rates appear to have lagged during the 1800s, were committing “race suicide,” hereditary organizations devoted themselves to policing racial purity. The DAR banned “colored” women by statute in 1894, the same year as the founding of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a group that, as Morgan dryly notes, “hardly needed a stated ban.” The DAR’s “lineage books” documenting members’ white pedigree (it produced 160 volumes between 1895 and 1938) were used in protecting against slurs and rumors. When Warren G. Harding ran for president in 1920, Republicans cited his SAR membership and a family tree “bundled,” says Morgan, “with ‘pallid, full-page portraits of his mother and father’” to battle rumors of mixed-race ancestry. He won in a landslide.

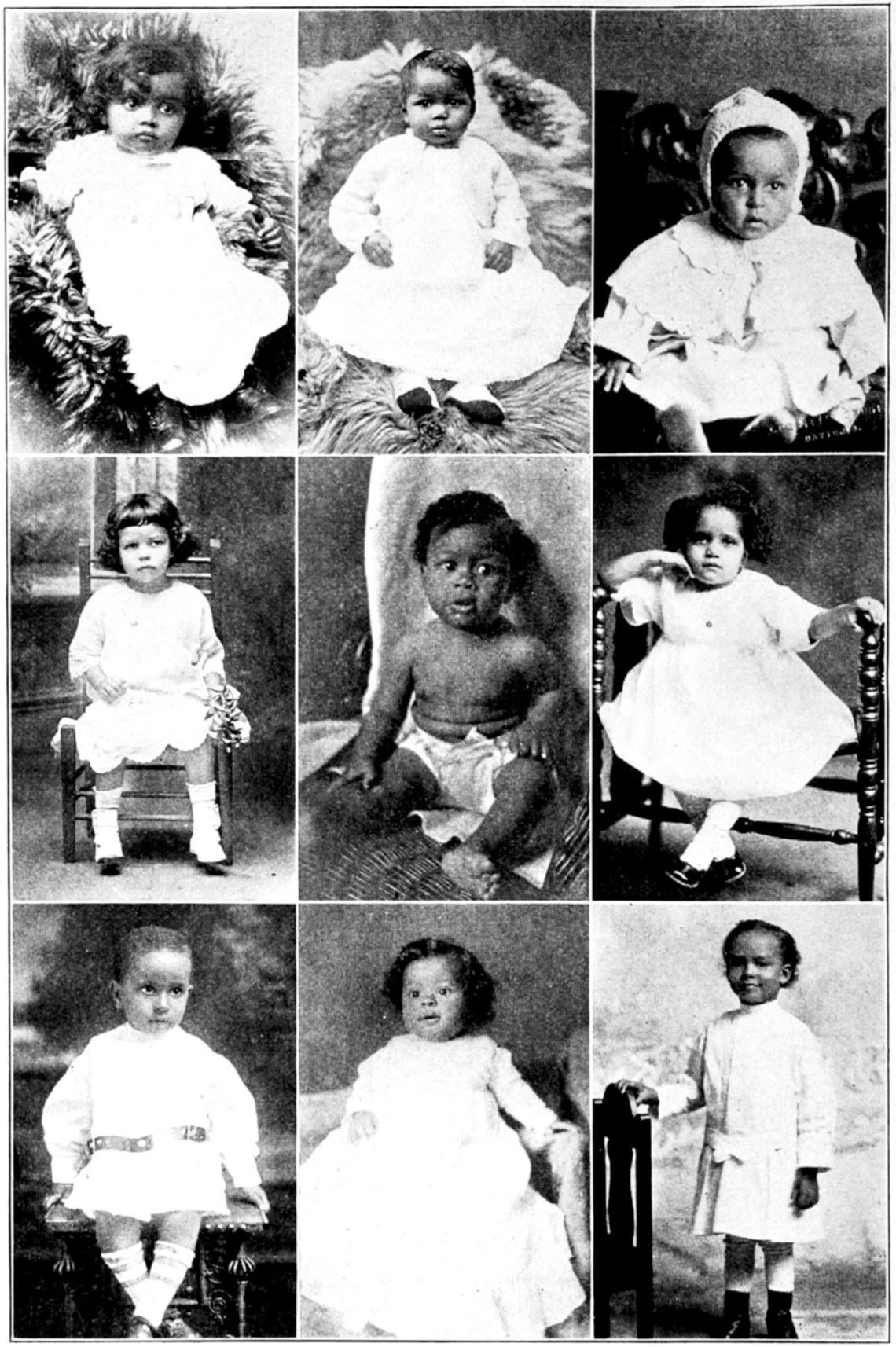

After W.E.B. Du Bois collected and submitted evidence to the SAR to prove his relatedness to a revolutionary soldier, he gained admittance to the Massachusetts chapter but was rejected by the national organization, which feared he might “repel white southerners from joining the Sons.” In the most moving chapter of Morgan’s book, she recounts Du Bois’s decision, as the editor of the periodical The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races (launched in 1910 by Du Bois and other members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), to publish a children’s issue in 1914 featuring eighty-nine photographs of babies and young children, submitted by readers and identified only by their state of residence. The images, a few reproduced by Morgan, capture pride and anxiety expressed through bows, ribbons, and ruffles:

The photographs show…cherubs and schoolchildren who were painstakingly dressed in white or light-colored clothing, carefully groomed, and generally Black or mixed-race. The older children’s toys, bicycles, and schoolbooks positioned them far from child labor, which was still widespread in factories, mines, and agriculture in the 1910s. These seemingly innocuous representations, that nonwhite babies, toddlers, and children could be clean, prosperous-looking, and well cared for, contested a bundle of racial stereotypes…. Wordlessly, the procession of impeccably dressed, round-cheeked children also affirmed the endurance of Black and brown people’s family ties in the face of wars of attrition on such bonds. Loving hands had bathed the youngsters, laundered and ironed their clothes, arranged their hair, and photographed them in a pleasing light. Loving attitudes had garnered the children’s cooperation. Babies and toddlers sat peaceably before the camera.

The photos were printed, she notes, at the same time that white-baby monuments were being put up around the country. By implication the images refuted “the presumptions of white supremacy” and the “social-Darwinist assertion that African Americans’ high rates of fatal illnesses and infant mortality demonstrated their inferiority to whites and forecasted a vanishing race.”

Du Bois’s baby pictures were just one sign of the importance of documenting family life and lineage, and Morgan provides detailed discussion of early genealogical efforts made by African Americans, Native Americans, and American Jews. Blocked by the national SAR, Du Bois wrote in The Crisis about his own and others’ connections to the American Revolution, supporting the formation, in 1930, of the first major hereditary group for African Americans, the Society of Descendants of New England Negroes.

Yet “genealogical trees do not flourish among slaves,” as Frederick Douglass wrote in 1855. Long after the end of the Civil War, research remained difficult for African Americans, who were often forced to resort to lore and oral sources. Marriages of enslaved people had no legal status and often went unrecorded, as did births. Descendants of former slaves eager to reconstruct their families’ stories were hard put to locate documentary evidence, Morgan writes: “Jim Crow stalked Black researchers even in the library. Public libraries in the South either excluded Blacks altogether or relegated them to inferior, segregated facilities.”

Better-situated scholars found a way. At Harvard, Caroline Bond Day, a mixed-race graduate student in anthropology, wrote her thesis on “Negro-white families in the United States” and published it in 1932. Although she encountered many who shied away from examining their ancestry and the history behind it, she interviewed 346 families, including Du Bois’s, recording their names, photographs, professions, and incomes. “Such people knew full well that displays of their faces and lineages, combined with evidence of successes, affirmed contemporary struggles against white supremacy,” Morgan notes. A teacher from Georgia wrote in response, “What a pleasure it is to know that our people are accomplishing great things!”

Advertisement

Day’s work was followed by that of the writer, poet, and civil rights activist Pauli Murray, whose genealogical exploration began when she was a teenager as a means of exposing what she called “Jane Crow,” referring to Black women’s experience of racism. She transcribed the recollections of her “race aunts,” building over some twenty years an extensive family history from oral interviews, archival research, letters, and albums. Published in 1956, Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family assembled a multiracial family tree. Her grandmother, born a house slave in North Carolina, was the biological daughter of her white master, and Murray’s book proved an important precursor for Alex Haley’s Roots.

From the Algonquin to the Zuni, indigenous peoples in the US possess a richly complex array of beliefs and knowledge surrounding their ancestry. But the federal government’s rapidly shifting policies and abrogation of treaties in the late 1890s threatened to replace such knowledge with its compendium of tribal “allotment rolls” and requirements surrounding “blood quantum,” referring to an individual’s percentage of Indian ancestry. Allotment and blood quanta became consequential measures affecting the distribution of land. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 defined an Indian as someone having at least one-half Indian blood, and legislation over the years had the effect of reducing tribal membership and the amount of land allotted. Tribal lists omitted those who refused to comply with enrollment, as well as those of mixed African American and Indian descent.

Morgan claims that her book is “the first long history of genealogy in the United States to incorporate Indigenous people’s genealogy practices,” but the survey, compared to the material on African Americans, feels shallow. Speaking of the “segmented nature” of tribal genealogy and the “decentralized” character of their resources, she remarks on the dispossession of native peoples without fully recording how ancestry and culture were disrupted by these events. “Such extremes as government bounties for the mass slaughter of bison, with which the state intended to starve out Native resisters, drew outcries from white reformers,” she observes, failing to note that there were bounties not just on bison but on the scalps of Dakota men, in Minnesota, after the US-Dakota War of 1862.

She mentions the high rate of white families’ “adopting Indigenous children” in the 1950s and states that “mass assimilation and Christianization for Native populations in the West resembled a humane alternative, at the time,” as if white interpretations of such policies were exculpatory. Her brief acknowledgment of “distant boarding schools” and “government-ordered family separations” skims the surface of that long, brutal era, neglecting to recognize the scope of the federal government’s program of “Indian schools,” begun in 1860. Designed to “kill the Indian [and] save the man,” many were run by churches. Tens of thousands of Indian children were seized against their parents’ wishes and placed in white homes or boarding schools, institutions where children were renamed and beaten for speaking their own languages. Some died of abuse and neglect, another method of reducing the amount of land that could be claimed. In this country, searches are ongoing for mass graves outside these “Christian” places; they have already been found outside residential schools in Canada.

One institution behind such adoptions was the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), a fact Morgan also fails to include. For its Indian Student Placement Program, which ran between the late 1940s and the mid-1990s, the church placed Navajo children in Mormon homes to work on their farms, an especially disturbing development given that the faithful had long believed that Native Americans were descendants of “Lamanites,” who, according to the Book of Mormon, rebelled against God and bore the curse of a “skin of blackness” and an “evil nature…full of idolatry and filthiness.” Believing this racist and fictitious genealogy, Mormons had seen American Indians as requiring conversion, while condemning African Americans to an even lower order. Blacks were specifically denied the priesthood, the main source of power and authority within the church. Spencer W. Kimball, an elder and later a president of the church, claimed in 1960 that the skin of Native American children became “several shades lighter” after they spent time in Mormon homes; Kimball was pleased that Lamanites were abandoning their “distorted tradition stories.” Morgan loses an opportunity to examine in detail the widespread destruction of indigenous families and the generational damage wrought by such attempts to annihilate children’s ancestral knowledge and culture.

Morgan does spend considerable time on the LDS, however, which has been assiduously tracking the genealogies of virtually everyone it could find for well over a century. Due to the structure of A Nation of Descendants—organized less chronologically than thematically, around exclusion and inclusion—Mormons keep cropping up in the text like prairie dogs and figure in the book’s more colorful passages.

The church’s dedication to genealogy originated in the unusual temple practice of baptizing the dead, which began with founder Joseph Smith. His 1836 revelations included instructions from on high on how to secure his late, unbaptized brother Alvin’s tardy salvation. Smith limited the practice to relatives, but within a few years Mormons were baptizing all and sundry, including George Washington, who was immersed by proxy in the Mississippi in 1843, forty-four years after his death. A later prohibition limited such baptisms to close family members for seventy years, even as a future church president reported, in 1918, a vision of Jesus Christ christening the dead.

Thanks to these preoccupations, the church became a considerable force in genealogy, led by the pioneering work of Susa Young Gates, one of the church leader Brigham Young’s fifty-six children from sixteen wives. One scholar has suggested that the church’s encouragement of genealogy may have been meant as a “surrogate for plural marriage,” officially abandoned in 1890. If so, these polygamous energies have borne prodigious fruit. In 1944 the church’s Genealogical Society of Utah opened its archives to everyone, for free, and the office gradually evolved from managing a “huge card file” to preserving everything on microfilm. In the 1950s Brigham Young University began offering the first college courses on the topic.

The church loosened its strictures on proxy baptism of the dead in 1961, just as American Jews were experiencing renewed interest in their heritage. Morgan notes the Nazi practice of using family records to identify Jews and reports one man asking a researcher if they even had genealogies. But in this country Jewish families’ post-Holocaust curiosity reached a heightened pitch with the popularity of the musical Fiddler on the Roof, which premiered on Broadway in 1964, a phenomenon that led researchers straight to the extensive records held in Salt Lake City.

With the publication of Roots: The Saga of an American Family in 1976, genealogical fever became a worldwide phenomenon. Both the book and the major television series that followed in 1977 had been presaged by Haley’s popular lecture series, which he launched a few years after the 1965 publication of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which he had cowritten. In 1967 Haley had made two trips to Gambia, where he asked villagers and a local griot, or storyteller, about dramatic tales he had heard as a child from female relatives about an ancestor, Kunta Kinte, kidnapped from the banks of the River Gambia and brought to this country as a slave, renamed Toby. With the information Haley learned there, he believed he had located the direct familial link to his African forebears, and his lectures served to build interest and to fund further years of research.

Primed by prior publicity, Roots spent five months at the top of the New York Times best-seller list, selling 1.5 million copies in hardcover and millions more in paperback. Airing over eight consecutive nights in January 1977, the tv show reached an unprecedented 130 million people. Black viewers especially became enraptured with the possibilities of diaspora narratives and “roots travel.” It was a watershed year: the DAR finally admitted its first African American member, although it took years to admit another. Apparently God watched Roots too, because a year and a half after the show aired, LDS president Kimball reported a revelation that Black males could now be admitted to the priesthood.

Morgan dutifully tracks the influence of Roots over the following years, as enthusiasm spread to other ethnic groups and countries. The first American Jewish genealogical society and periodical were founded shortly after the book appeared, along with new organizations devoted to Hispanic and Latinx ancestry. In another baffling omission for someone chronicling exclusion, Morgan barely mentions Asian Americans. Amy Tan’s 1989 novel, The Joy Luck Club, doubtless served as another such turning point, exploring ethnic and cultural identity and the problems of assimilation.

Morgan is much better on Roots itself and its complicated afterlife as a high-profile example of the uses and abuses of genealogy. The book had been published as nonfiction, but gradually reviewers and readers raised questions about its historical accuracy.* Haley came to refer to his work as “faction” (a mixture of fact and fiction) or “the saga, of us as a people,” acknowledging that dialogue and other elements had been fictionalized. In addition, there were lawsuits based on accusations of plagiarism. Morgan assiduously untangles these scandals but also points out that, for most readers, they hardly seemed to matter. For many African Americans, Roots in all its forms fed an insatiable hunger to know their origins and, as one educator put it, “helped destroy the chilling ignorance of who we are as a people.”

The reach of Roots was such that the National Archives and the LDS genealogical holdings were mobbed with seekers from all over the world. So it was inevitable that the church’s renewed taste for proxy baptisms of the dead would come to light, as it did in 1993, when Gary Mokotoff, the publisher of a prominent Jewish genealogical magazine, discovered that Anne Frank and others who had perished in the Holocaust were baptized posthumously. He declared such acts “particularly repugnant to Jews,” subjected for centuries to forcible conversions. The church banned the practice again in 1995, but Mormons keep doing it, recently splashing out to net the grandparents of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

Genealogy has now been radically transformed by digitization, elevating it to a commercial powerhouse, its resources increasingly available to all. In 1990 two graduates of Brigham Young University began selling LDS publications on floppy disks from the back seat of their car. By 1996 they launched a website, Ancestry.com. Now boasting more than three million paying subscribers in thirty countries, the company brings in over $1 billion in annual revenue. It was sold to a private equity firm in August 2020 for $4.7 billion. Since 1999 the LDS church has operated a nonprofit search engine, FamilySearch.org, offering access to many of the same sources as Ancestry for free.

A major difference between the two services is that Ancestry.com sells DNA home-testing kits, whose results can be incorporated into family trees on the site. According to Bloomberg Law, some 18 million people are represented in Ancestry.com’s DNA network. Millions more have availed themselves of other tests, such as those sold by 23andMe, and the data collected on multiple sites have corrected the record on historical figures, identified long-sought criminals and human remains, and startled any number of customers who have learned hitherto unimagined facts about their families.

Among the most notable of DNA revelations concerned Thomas Jefferson. For decades, despite rumors and resemblances, historians adamantly denied that he could have fathered children with Sally Hemings, his house slave and the half-sister of his deceased wife. In 1997 the historian and law professor Annette Gordon-Reed published Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, assembling and examining ample textual evidence for the connection. The following year, Nature published an article on DNA results from putative male descendants of the pair showing, in Morgan’s words, “a very high probability of biological relatedness.”

That’s the kind of gasp-inducing disclosure sought by DNA reality shows, the most beloved of which stars the Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. Beginning with African American Lives (2006 and 2008) and moving on to Faces of America (2010) and Finding Your Roots (2012–present), Gates has featured celebrities being presented with “books of life” telling the story of their ancestors, assembled by teams of experts in genealogy and DNA. Gates talks his subjects through the pages, inevitably reaching a dramatic “reveal.” Oprah Winfrey learned, for example, that a great-grandfather, an illiterate man named Constantine Winfrey, received eighty acres of prime Georgia farmland from a white man, in exchange for growing and picking eight bales of cotton, or more than three thousand pounds, within two years.

Morgan sneers at “entertainers’ trafficking in emotions,” as if emotion were fentanyl, discussing Gates in the same tone with which she describes Maury Povich, the trashy talk show host of the 1990s infamous for outing deadbeat dads with DNA tests. In some ways her skepticism is justified, since Gates had to apologize in 2015 after bowing to pressure from Ben Affleck to delete material documenting that an ancestor of his owned slaves, an anecdote she does not include. The popularity and influence of Gates’s shows—which at their best provide an accessible induction into American history—make them relevant to her discussion. Yet she devotes as much space to a genealogical episode of SpongeBob SquarePants as to what Gates has done, missing the point of both his shows and contemporary genealogy as a whole. Americans desperately want stories about their past, and it was presumably the job of this book to ask why.

If anything, genealogy thwarts our emotional needs, revealing only fragments of a story. The data are, almost inevitably, scant and narratively disappointing. There are revelations to be had, but barring letters or diaries to flesh out the tale, seekers are often left holding a skein of tantalizing connective tissue, nothing like a complete corpus. As Haley put it, we have “a hunger, bone-marrow deep, to know our heritage…a hollow yearning…a vacuum, and emptiness, and the most disquieting loneliness.”

For most of us, we’ll never receive a tidy “book of life,” padded with historical stuffing, like those on Gates’s shows, because genealogy is elusive, expensive (in time and money), and frustrating. We may be able to trace our ancestors’ DNA, but we can’t know or recreate in much depth the motivations or behaviors of our great-great-great-grandparents, any more than we can know those of William the Conqueror or Adam or Eve. In that sense, Roots remains a discomfiting example of that yearning we feel, looking back across time, and the fictional extremes it may inspire. It took a creative writer to fill in the unbridgeable gaps and breathe life into characters who had, by the time their belated author came along, succumbed to the void.

-

*

See Willie Rose Lee, “An American Family,” The New York Review, November 11, 1976. ↩