Rose Wylie, who is now eighty-seven, has been painting in the same rural studio in Kent, England, since the late 1960s, but she has only recently shimmered into wide public view. Incredibly, the show of large-scale paintings held last spring at David Zwirner was only her third appearance in New York, and the first in a big-time gallery.* She who laughs last and all that.

Wylie is the opposite of what comes to mind when you think of an artist of a certain age rusticating in the Home Counties. She is a painter of verbs, and her large canvases (typically six feet by ten feet, more or less) are full of action: people dancing, playing sports, ice-skating, vamping, or working at a task, like butchering meat or driving a car. Her approach to form is boldly idiosyncratic; her brush shoots around the whole body, and the way she paints people is like stylized Morse code: the eyes and mouths often reduced to mere dots and dashes, the hair a mass of wavy brushstrokes, and the flattened forms heavily outlined in thick black or red oil paint. Wylie has a thing for faces seen in profile, and bodies too, maybe because they are easy to animate at that angle, and they give her paintings a jaunty, spirited feeling. Her work projects a “can-do” attitude; it’s full of pep.

She gets a lot of mileage out of painting eyelashes, as well as full skirts, soccer balls being kicked, brick walls, and ocean waves—anything that can be represented by rhythmically organized lines and sets of lines. Her streamlined figures project speed and immediacy, but they are not just hieroglyphs. The handmade quality, the feeling of an image arrived at through careful in-the-moment looking, is always present.

In the syntax of painting, the quality of line and the amount of pressure exerted in its making endow a painting with a good part of its energy. Wylie’s grasp of mark-making is almost outrageously assured. She shows how line can both describe an image and at the same time be an image. Her confidence that the brush is doing the right thing never wavers.

Where did she come from, and why hadn’t we seen her before? Although Wylie (born in 1934) is a contemporary of David Hockney, she is part of the generation of English painters who came of age after he reset the clock on British art. In Britain before 1960, even modernist-inflected painting was largely based on direct observation—i.e., realist—or loosely illustrational, something that looked good on the page. There was more, to be sure: homegrown abstraction, like John Hoyland and his confreres, the St. Ives landscape painters, not to mention the distortions of Francis Bacon and his school. But the dominant modes were scenes painted whole rather than fragmented, in either a version of straight realism or a more fanciful and illustrative modernist shorthand.

Hockney collapsed the two modes into one and introduced a fractured pictorial space into the bargain. And his finely calibrated distance from both popular culture and art history could be seen as gently, affectionately ironic. Although irony had long been a favored literary device, Hockney was among the first painters to give it visual form. By the 1970s, the ironical quoting of cultural motifs was commonplace—the pictorial equivalent of making notes in the margin of your copy of Shakespeare’s plays—but the level of finish seen in English painting was generally refined. The kind of paintbrush-as-meat-cleaver attack that Wylie carries out now would have seemed gauche in the 1970s. Her work was, and remains, barely housebroken.

Wylie showed early promise in drawing and painting. She attended a local art school as a young woman and went on to the teacher-training course at Goldsmiths in London, where she met the painter Roy Oxlade; they married in 1957. After graduating in 1959, the couple found a farmhouse in Kent with dilapidated barns that could be used as studios, and began a life dedicated to painting and teaching and getting by. They had three children, and Wylie put her own work on hold to care for them more or less full-time. Twenty years went by. She returned to school in 1979, at the age of forty-five, this time at the Royal College of Art, at the beginning of what would be a very consequential decade for painting in general and for English art in particular. Something catalyzed then in her work, though it would be years before it started to attract serious attention. Eventually she was included in a couple of important group shows, regional museum shows followed, and then the dealers came calling.

Wylie is no outsider artist, and her work should not be celebrated simply because success found her late in life. She is the real deal, and it took as long as it took. I’m just glad that she stayed the course. Her modernist bona fides are most apparent in her casually brilliant cut-and-paste compositions; she strategically distributes her forms across the canvas in a manner that recalls the repeats of sophisticated wallpaper or fabric design, two high points of English visual culture in the mid-twentieth century. In a final nod to craft culture, she often embellishes her works with strokes of paint aligned with the canvas edge, like a hand-painted frame.

Advertisement

The whole effect is so blithely “I don’t give a damn about fashion” as to be totally winning. One simply surrenders to her way of looking at things. Wylie’s paintings call to mind something John Cage once said in a documentary, with his inimitable, grinning, I-might-be-a-fool optimism, about his efforts as Merce Cunningham’s rehearsal pianist: “If you think the music’s bad now, just stick around.” She is interested in the vitality of seeing, not in realism, and if that results in some strange-looking heads and Kewpie-doll lips, that’s not her problem.

She finds much of her imagery in magazines, advertising, televised sports, or films. Many of her canvases feature athletes—tennis players, figure skaters, swimmers—which possibly makes her the only serious artist since Degas to take up the sporting life as a subject. Sometimes she paints what’s outside the window—a cat, some grass, a tree—but most of her paintings are of things that have already been pictured in one way or another. Her subject is simply whatever catches her eye.

Most artists are good noticers, and Wylie registers the stuff that we might all see in passing but usually decide is too banal or would require too much effort to translate into a visual shorthand. She paints a TV dance-show contestant in rather the same spirit as Jasper Johns paints the American flag: both paint what the mind already knows but the eye often skips over. What differentiates her work from that of other noticers of the quotidian, like Luc Tuymans, for example, is her interest in the bright surface of celebrity. Wylie doesn’t have a censorious attitude toward her subject matter—she’s neither superior nor a prude. Her images arrive on the canvas with an impartial delight, like the way a child might blurt out, “Look at that fat guy!” Her work feels unencumbered by the language of therapy or politics—that’s part of its great freedom.

Painting images is fundamentally a matter of translation, and Wylie’s thick impasto lines are a record of her taking on the spirit of her subjects, attempting to draw herself into the way something makes her feel, like the sense of ebullience we get from watching a champion athlete compete. Wylie transforms spectatorship into something protean; she’s the Cézanne of channel surfing.

People have been putting paint on canvas for centuries, during which the materials haven’t changed much. What distinguishes every painter is the specific qualities of touch, the way the brush makes contact with the canvas. This is part of what is called an artist’s style, and more than anything else Wylie’s work is defined by her mode of dragging paint over unprimed cotton, the loaded brush giving way to scumbled, dry-brushed edges on her shapes and marks. She applies paint to canvas in much the same way that one would apply icing to a cake—spreading it out thickly to the edges. That’s what came to mind when I first looked at her paintings, and I was pleased to see her use the same analogy in an interview. She makes much of the inherent drama of the raw cotton’s resistance to the drag of the paint; the way it comes to rest at the edges of a shape is the stuff of painterly drama. (Clyfford Still pretty much made a career out of it.)

Wylie uses several different ways of applying paint. In addition to the cake knife and the scumble, there are the wavering, overpainted line, the chunky block letters built out of short strokes, and what looks like flicking paint off the edge of a palette knife, with thick globs hitting the canvas here and there. Her other device is the overpainted outline that gives definition to her otherwise approximate figures, and to details like hair and clothes and other accoutrements.

The important part—one wants to say the art part—is that all of Wylie’s lines and marks and paint drags are also shapes. This is the first principle of painting, and Wylie takes it to heart. Then she explodes it. She also has the great gift of knowing when to stop.

Wylie’s way of using a paintbrush to describe form is direct and unfussy, but achieving that effect is more complicated than it looks. The unarguable, gutsy outlines are the end point of a process of remembering and refining. I gather that her method is something like this: she sees an image in a magazine or on TV, say of a tennis match, and then, days or weeks later, makes charcoal drawings of it from memory, deliberately letting time go by so that only the essentials remain. The drawing is the sum of specific details that stay in the mind’s eye after the original image has faded. These drawings, reworked and reanimated, sometimes cut up and collaged together, then form the basis for the paintings.

Advertisement

This translation from memory to drawing is one of the factors that give Wylie’s work its sense of freedom; the forms, though inspired by something pictured in the media, seem to spring directly from her head. Straight, observational realism is for wimps. She doesn’t worry about things like shoulders or necks when painting her figures, and especially not hands (why bother?); arms are like strands of pulled taffy that end in narrowed stumps, sometimes with only the slightest nubs for fingers. Legs are like Gumby dolls, or hams, or tadpoles; and feet are either impressively shod or appear as small triangles. You can imagine her unapologetic inner monologue while painting: Oh, did I forget to give that person a shoulder? I didn’t think he needed one. Wylie is not painting a person in any case, but her memory of a picture of a person. Nevertheless, in the alchemy of paint, her figures are full of personality: they kick and leap and fly around the canvas.

Sometimes her paintings feature preposterously enlarged views of quotidian reality. Breakfast (2020) is a ten-foot-long rectangle in two parts that features a white plate with a blue scalloped rim floating on a mostly black background. On the plate rests an enormous black spoon, a rectangle of scumbled gold-orange paint (yogurt? porridge? toast?) and a few berries scattered around. The scaling up of an intimate domestic image, painted with the finesse of a road crew laying down asphalt, is mind-expanding. It’s as if Bonnard had taken a tab of acid with his morning café au lait and suddenly picked up a three-inch-wide brush instead of his habitual quarter-inch filbert. Yet even when she is slathering on great globs of paint, her touch stays purposeful and light.

Wylie often incorporates the titles into her compositions, either with capital letters of thick impasto (Breakfast) or with an elongated, condensed typeface, like the kind used for elegant moderne stationery in the 1930s and 1940s (Fluffy Head, 2020). The impulse to write on paintings, to make design elements out of letters and words, has shown up periodically in Western art for over a century, but Wylie makes it feel new. In Breakfast, the title is spelled out in caps in broad, semicareful brushstrokes of raw sienna along the bottom edge on the black ground. The scale is declarative, like someone shouting into a megaphone. The big blocky letters are also kind of slapstick, like a pratfall or a poke in the eye. Get it?

Wylie’s belief in her own choices is bracing; she calls to mind Frank O’Hara’s dictum “You just go on your nerve.” On first glance her paintings may appear to be blown-up drawings made by a blithely unselfconscious child. In the next instant, their deliberateness and formal sophistication swamp that initial impression; every mark and color and wonky bit of drawing is fueled by a decisive engagement with painting, carried out with a disregard for the conventions of representation. She fits the late artist and film critic Manny Farber’s description of the “termite artist”: an efficient and unconcerned omnivore tunneling under the surface of things (or on the surface, in this case), taking only what she can use and discarding the rest.

Wylie’s concern is for the way we experience the world as a series of still pictures, often in close-up, and how those pictures can be bigger and more persuasive than the real thing. She’s a twenty-first-century painter of modern life, an “I am a camera” with a brush. With their distilled forms and self-captioned texts-as-titles, Wylie’s pictures are like memes in paint. But none of this ontological filigree would matter very much if it weren’t for her ability to orchestrate the formal elements of painting into an indivisible whole. Her gift for making an overlooked bit of cultural signage into a surprising image is combined with an uncanny sense of where and how to place it within the overall composition; she deploys her mnemonic distillations with a collagist’s sense of mobile improvisation.

Both aspects of her art—the noticing and the arranging—are underscored by a tremendous freedom to bend the image to her subjectivity, to cut it up and move it around on the canvas at will, and finally to combine it with fragments of ornamentation or other bits of painterly derring-do. Her motto could be “Amuse thyself,” and her method summed up as “improvise, then revise.” Her work is a good example of the absolute specificity and the in-the-moment control necessary to make a painting rise above the predictable.

Wylie is also something of a sponge. The list of artists with whom she intersects, visually or spiritually, goes all the way back to the Egyptians. She’s attracted to how artists working before the invention of perspective used highly stylized, static figures in rhythmic sequences to convey continuity and movement, and Byzantine and early Renaissance paintings are echoed in her hierarchies of scale and placement. Skipping ahead a few centuries, Wylie shows fellow feeling for Francis Picabia, that other master of the overdeliberate eyelash. Artists of the more recent past such as Neil Jenny, Georg Baselitz, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Donald Baechler, William Copley, Lee Lozano, and Judith Bernstein come to mind in large or small ways as either precursors or fellow travelers. They all share a sensitivity to mark-making and a blunt image shorthand that owes something to outsider art and early comics. Wylie seems to have taken cues from or at least looked at them all, pumping up the scale as well as the anecdotal humor.

Some of Wylie’s paintings look as though they began life as drawings by the master ironist Sigmar Polke. A crucial element in Polke’s drawings was the ability to convey the subtle relationship between mockery and admiration. Wylie shares that sensibility, and her choice of images can be just as endearing. Choco Leibnitz (2006) depicts a cookie—the brand shares a name, give or take a letter, with the seventeenth-century German philosopher—about to be popped into an enormous open mouth. The lips edged in red, along with the nose and chin, are seen in profile at the painting’s left edge, while the cookie itself appears to fly through the air, accompanied by a few black lines signifying motion. For reasons that may have to do with the depiction of time and space, the last two letters of the logo—“T” and “Z”—break free of the cookie’s surface on their journey to the open mouth. The wackiness of the concept, along with the directness and simplicity of the staging, evokes Polke’s affectionate appropriations.

But perhaps the artist with whom Wylie has most in common is Julian Schnabel, especially with the work he was making from 1979 to about 1982, which coincided with her return to art school in London. Although she has said that she was unaware of his work at that time, she would likely have been exposed to it as well as that of his cohort at “A New Spirit in Painting,” a groundbreaking exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art in 1981. In any case, it’s not a question of influence so much as what was in the air, what the permissions were at the time, and how those permissions were changed or enlarged by individual talents. What both artists share is a method of transferring greatly enlarged details of a sketch onto a huge expanse of canvas using a large brush.

There’s a common perception of Schnabel’s work that it’s bombastic and walks with a macho swagger, a mischaracterization that was leveled at an entire generation. This is mostly nonsense. Especially in the early 1980s, Schnabel’s work had a delicacy and refinement even at large scale. Both he and Wylie seek out subjects that convey a kind of enchantment, or whimsy, and they both use charm as a means of persuasion. It’s tantalizing to think that the two of them, separated by an ocean, arrived at such similar styles autonomously, but in any case the emphasis on who did what when is often misplaced. Art doesn’t really “progress” as such, but artists often advance in their own work by confronting the work of others; they sense a liberating possibility in a way of painting and adapt it to their own sensibility.

There is an important difference between influences—the rich stew of aesthetic kin—and actual sources. The first is like weather while the second is more of a template. One type of visual narrative that has been a source for Wylie is the tradition of Mexican folk-art paintings known as retablos, which began in the eighteenth century as small devotional scenes and evolved in the twentieth into printed books of condensed, campy narratives that abound with images of grief, eros, violence, comedy, or religiosity. Retablos typically feature an illustrative scene with a handwritten commentary in a separate box underneath. In the Zwirner show there were several works whose titles included the phrase “homage to retablos painting,” and Wylie milks the format for all its narrative compression and compositional audacity. The retablos world seems to have given her not just the “storyboard” format with the handwritten surmise, but also a quirky, less than anatomical approach to painting figures: the small heads with tiny features and approximate hair, and the rubbery limbs that extend from shoulderless bodies.

Wylie’s work projects an externalized, outwardly focused view of the world that nonetheless insists on its own subjectivity. Her subject overall seems to be the exhilaration and self-validation that result from importing things in the world to the realm of the painted—a kind of constructed enchantment. She’s the Sugar Plum Fairy of painting. Of course, this kind of thing has been going on forever, but she finds a way to make it feel new. Wylie has said that she comes from the tradition of painting what she sees out the window, but I suspect that her real fixation is the way things come to us through cultural ephemera, with some more observational motifs thrown into the mix. There’s a sense of wonder at how the commercial world seeks to create in the casual viewer feelings of hierarchies, logic, and coherence—of cause and effect. The conventions and assumptions of pictorial presentation, the world as it represents itself, are what seem to hold her attention; the charm and absurdity encoded in the most banal types of images incite her.

Scale is an important aspect of Wylie’s pictures; it’s part of her self-assurance. Working on nine- or ten- or even twelve-foot-wide canvases necessitates the use of large brushes and the whole arm in the application of paint. No place for noodling, to use Alex Katz’s term for hedging one’s bets while painting. And bumping up the size helps prevent Wylie’s images from being read as twee or merely eccentric, which can be a problem when working at a smaller scale. Some of her images—tree bark, a spider, a leaf—convey the pleasure of looking at things under a microscope. The spider imagery even extends to the rendering of human forms: one of Wylie’s more hilarious inventions is a facedown figure viewed from above, like a swimmer in the water or a baby crawling on the floor. This bird’s-eye view—combined with Wylie’s disinclination to draw hands and feet, and the cocked or flexed arms and legs that end in pointed stumps—amplifies the arachnoid metaphor.

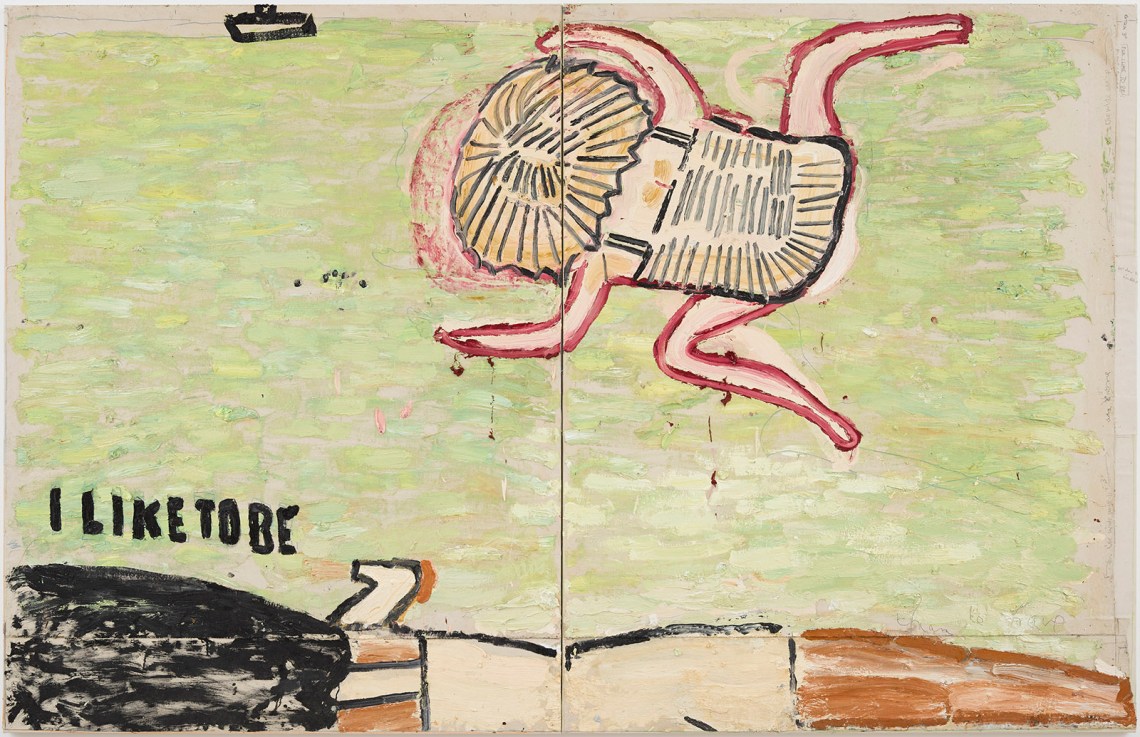

One painting in particular will exemplify what I mean. At more than ten feet long, I Like To Be (2020; see illustration at beginning of article) shows two female figures facedown in water. The one near the top edge is engaged in some sort of breaststroke, limbs bent like the legs of a crab, the bottom of her bathing suit poufing out like a baby’s diaper, her thick black lines of coiled hair semi-floating in the green, foamy water. Her body, outlined in viscous strokes of carmine-red oil paint, could be a bathing-suit-wearing crustacean: there she floats, oblivious to our gaze. The lower bather, also face-down, is cropped in half by the canvas’s bottom edge, and her body is fantastically elongated, stretching across the the painting’s entire width, her mass of black hair surging improbably forward, while her right arm, disproportionately shrunken, is cut off at the point at which it plunges into the water. It’s the image we have in the mind’s eye as we push away from the wall of the pool, arms outstretched before us as we glide through the water—the sensation of the streamlined body getting longer. Two swimmers facedown in a wide green sea, one half crab and the other mostly squid, poised amid the horizontal brushstrokes of sea-foam green, with I LIKE TO BE in chunky black letters giving voice to the emotion. It’s a thrilling picture; I’m tempted to have the words tattooed on my biceps.

Wylie is also a sophisticated colorist. The pale ocher color of the raw cotton canvas that she uses is a constant, and other colors show up fabulously against it. Many of her paintings feature a wonderful harmony of sugary pink, cadmium red light, plus pale lemon yellow, raw sienna, or yellow ocher, and she is partial to a green so minty it’s almost aromatic. Colors are not often blended—once a color is mixed, it’s used as itself, defending its territory against incursions. Sometimes a cobalt or ultramarine blue will be mixed with white and slathered on the canvas in close-packed horizontal strokes, like sardines in a tin, and white itself is frequently used for backgrounds or for punctuation. Wylie is a connoisseur of yellow—a notoriously difficult color to use—deploying it for figures, hair, or dresses, edging it most often with cadmium red, but also with cadmium green, or turquoise, or brownish black. Wylie puts more yellows to work than any painter since Baselitz.

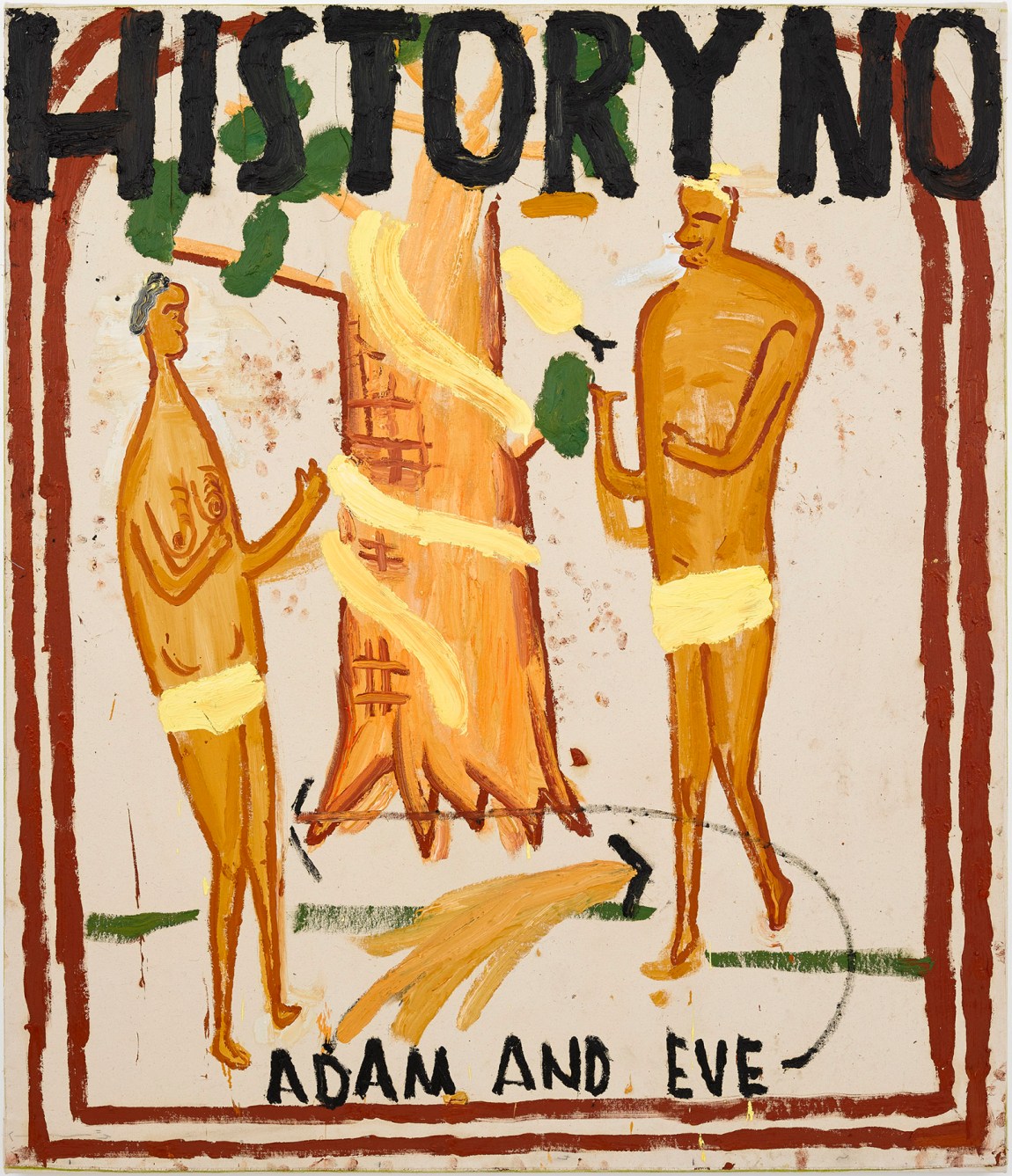

The Zwirner show contained one of the weirdest paintings I’ve seen in years: Illuminated Manuscript, Adam and Eve (2020). A medium-sized vertical canvas is bisected by an ocher-colored tree flanked by a female figure on the left and a male figure on the right. This is Adam and Eve as you’ve never seen them before: Eve is roughly the shape of a carrot, with a face like Popeye’s and what looks like a shower cap on her shrunken head. A pair of breasts flaccidly descend to meet two shoulder-less Gumby arms. Adam has broad shoulders but the same rubbery arms, one of which ends in an upturned hand that resembles an elephant’s trunk. Both figures are painted in the same raw sienna as the tree, with a little darker ocher here and there, and all are outlined in a dark red. Where the genitals—or fig leaves, in the medieval renditions—would be, Wylie has supplied broad swaths of pale yellow paint applied in vigorously clumsy strokes, as if she’s scrubbing a floor, and the same yellow paint wraps itself diagonally around the tree, becoming a de facto yellow serpent.

Across the painting’s top edge, heavy, blocky letters of a dark cadmium green spell the words HISTORY NO, with the same color used for the names of the protagonists in smaller type along the painting’s lower edge. As if all this was not enough arbitrariness, Wylie adds two parallel lines of the same dark red to form a border around three sides of the canvas, rounding off to an arc before exiting at the top. I haven’t seen a painting this unhinged from the conventional in a long time. It sends up pretty much every piety there is while being shamelessly stylish at the same time—beauty strictly on its own terms.