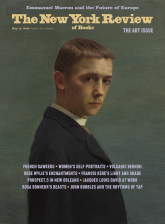

1.

The suits of recent French presidents—all men—say more than you might expect of navy blue. Nicolas Sarkozy, caught between the competing billionaire heads of France’s luxury empires, navigated favoritism by dressing in the Italian designer Prada. François Hollande, the last Socialist president of the country, was widely mocked for the tight jackets that stretched around his plump chest, making him look like he didn’t know what size to wear. Deeply unpopular and considered incompetent, he did not run for reelection.

So it was a surprise to see photos in mid-March of the current president, Emmanuel Macron, unshaven and in a black hoodie with the insignia of French paratroopers, looking a little like Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. Macron is forty-four and is usually well dressed in a slim blue suit. When he ran for president five years ago, he did what he could to present himself as mature enough for the job. Tabloids reported that he had trained his voice to sound deeper. Now, it seemed, he wished to send a different message: war had returned to Europe, and he, like Zelensky, was leading the people—albeit from a gilded room in the Élysée Palace rather than a bunker in besieged Kyiv.

For weeks Macron had scarcely admitted that he was running for reelection. As his old far-right rival, Marine Le Pen, and his new far-right rival, Éric Zemmour,1 sparred in the press to see who could offer the most outrageous proposals about immigration and racial identity in France, Macron held himself apart. He did not announce his candidacy until the beginning of March, and when he did so it was not with a speech but with “a letter to the French,” which he released less than twenty-four hours before the legal deadline to be on the ballot in the first round of voting on April 10, and which appeared in several newspapers.

Perhaps buoyed by his initial lead in the polls, which soon evaporated, he refused to debate the other candidates vying for the presidency. In fact, he refused even to campaign until the last minute. When the main French broadcaster, TFI, hosted a televised event on March 14 bringing together eight of the twelve people still in the race, Macron insisted that he would participate only if each one was questioned alone by two journalists. For nearly three hours, the candidates stood awkwardly onstage, one after the other, and spoke about the retirement age or energy prices.

Instead, Macron has concentrated his attention on Ukraine: to date, he has spoken more than a dozen times each with Vladimir Putin and Zelensky, who suggested to The Economist on March 25 that he was not particularly impressed with Macron’s regular conversations with Putin before and after the invasion. France and other countries are “afraid of Russia,” Zelensky said.2 Macron’s diplomatic effort has given the somewhat bizarre impression that his interests are elsewhere and that he simply hasn’t the time to earn anyone’s vote.

On April 10, Macron came out ahead of the eleven other candidates with nearly 28 percent of the vote, but Le Pen was less than five percentage points behind him. A low turnout, especially among younger voters, did not work in his favor. If the same occurs in the second round on April 24, Le Pen could become president, with drastic consequences for both France and Europe. The daughter of a convicted Holocaust denier, whose party has been directly funded by Russian bank loans in the past, could assume power at the very moment that Putin threatens Western Europe and its security alliances. She has said that as president, she would push for what she calls a “strategic rapprochement” with Putin. If she wins, Macron will have only himself to blame. The election is his to lose.

The day after the vote, Macron was interviewed by France’s BFM television network in the northern French town of Carvin, in the predominantly working-class Pas-de-Calais, decidedly Le Pen country. He was sitting in an everyday corner café in what looked like an attempt at the diner dispatch beloved by American journalists in the Trump era—except that Macron, now out of his hoodie and back in his immaculate navy suit, was alone with the reporter and cordoned off from other customers.

The journalist Bruce Toussaint began the interview by asking Macron what he thought about the fact that in Carvin, 40 percent of locals backed Le Pen, 21 percent went for the far-left Jean-Luc Mélenchon, and only 19 percent voted for him: “What would you say to this France, peripheral France, that struggles, that often feels abandoned?” Macron’s smile cracked a bit, and he began by congratulating himself on coming in first. When he actually answered the question, his words were garbled. “When I see the fractures, when I see the statistics you cite…my desire is to go out and convince,” Macron said. But he has not done much of either.

Advertisement

At a small campaign event in Pau in the Pyrenees on March 15, Macron spoke on a black dais with a white column, before locals who had been selected by the regional newspapers. Behind him, the mountains were covered in mist. One woman complained about a factory that had moved offshore. Forty-seven jobs had been lost. A student asked an aggressive question about climate change, then pressed him on tax cuts for the rich. Another asked about why it was so difficult for rural students to be accepted by France’s top schools.

Pau is a town of 75,000 people. Its mayor, François Bayrou, is a close ally of Macron’s. In the days leading up to the event, there had been speculation in the press about the questions Macron would receive from the audience. After an earlier campaign event near Paris, reporters had revealed that the questions had been submitted and chosen in advance. Macron needed to give the impression of a more authentic dialogue this time. His answers often delved deep into technical details—the answers of a class presentation rather than a president.

The war in Ukraine was barely mentioned. But after three hours, Macron said he was going off to make an international phone call—to Putin. He hoped, he said, “to convince him to return to negotiation.” “I’m not naive,” he continued. But “there’s a path”—he pointed to the mountains—“a ridgeline…. We have to do everything we can to find it.” Macron’s own path is no longer as clear, and even if he is reelected, it may already be lost.

2.

When Macron was elected president in 2017, he walked onto the stage in front of the Louvre to the strains not of “La Marseillaise” but of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” the official anthem of the European Union. This was the first overture of the “revolution” that he was meant to bring: his election was billed not merely as a watershed moment for France but for all of Europe. “You have chosen audacity,” Macron said to the crowd gathered that chilly May night. “And the audacity of a new future.”

Five years later, at the end of Macron’s first term, the “revolution” has and has not arrived. It turned out to be Macron himself who was—and is—audacious, not so much his presidency, which has unfolded during the Trump administration, the coronavirus pandemic, and now the return of war to Europe. His election did constitute a revolution in French national politics, in the sense that it completely overhauled the political establishment as it had existed more or less since the time of Charles de Gaulle, the founding father of the Fifth Republic in 1958. Since then power had changed hands between some variation of de Gaulle’s mainstream conservative party and the Socialists, the champions of the welfare state whose greatest president was François Mitterrand. Macron, who had been Hollande’s finance minister, launched something of a coup: he broke with his old boss, founded his own party—initially named “En Marche,” for his initials, E.M.—and created the closest thing France has ever had to a centrist “Third Way.” If you vote in France today, you either support Macron’s amorphous centrism despite your misgivings, or you vote for extremists of the right or the left.

Macron neither tried nor pretended to be the président normal—the normal guy—that Hollande had promised to be; in fact, he strove to be quite the opposite. From the beginning, he styled himself—unironically—as Jupiter, gazing at his subjects from Olympian heights. He is among the most image-conscious figures in European politics today. Shortly after his election, when he posed for an official portrait, he chose to stand in front of his desk, displaying his youth and vigor. One of the books chosen for the desk was Stendhal’s The Red and the Black, which seemed to suggest a certain inspiration, coming as he does, like Stendhal’s Julien Sorel, from the provinces (Amiens for Macron, a village near Besançon for Sorel). There are further similarities between the two. Macron likely sought to channel Sorel’s ambition and passion, but the truth is that he is less a character out of Stendhal than out of Balzac, the great chronicler of the petty bourgeoisie, its hypocrisy, and its aspirational ascent. He is far more like Eugène de Rastignac than Sorel: Rastignac’s designs ultimately succeed, and he even becomes a government minister. But every detail of his persona is heavily manicured, and a certain amount of envy fuels his rage and his drive for social advancement.

Advertisement

Macron is an upstart, a former investment banker who has struggled to connect with rural France in the way of his predecessors, as with Jacques Chirac’s lifelong bond with Corrèze or Mitterrand’s annual pilgrimage to climb the Rock of Solutré near Mâcon. He considers himself an intellectual and can never seem to give a press conference that is less than a multi-hour ramble, so nuanced, it seems, are his thoughts. In foreign affairs, he considers himself a major player and believes that his personal charm can sway strongmen and autocrats. But it never quite works out that way: Putin invaded Ukraine despite Macron’s attempts to dissuade him, and Trump tore up the Iran nuclear agreement despite Macron’s 2018 state visit to Washington, where he was convinced that eleventh-hour negotiations would change Trump’s mind. Once again, his suit became political, although this time as a source of embarrassment. Trump led Macron along only to humiliate him, flicking a piece of dandruff off his lapel in front of the press pool.

Domestically, Macron has embraced his balzacien instincts and courted the business establishment, which had been horrified by the 75 percent “supertax” on earnings over €1 million that Hollande had promised after his election and then abandoned two years later under pressure. Macron’s finance ministers have mostly been former members of the traditional conservative party, the Républicains, and in economic matters he has been a center-right president more than a centrist one. One of his major achievements has been a series of labor reforms that, among other things, have made it easier to hire and fire employees. As a result, despite the disruption of the coronavirus, France’s perennially high unemployment rate has actually fallen from about 10 percent when he took office to 7.4 percent, its lowest level since before the economic crash of 2008.

France has had right-wing presidents before—in fact, despite its image as a model welfare state, it has mostly had conservative presidents since 1958. But none, not even the brash Sarkozy, has elicited the staggering amount of vitriol that Macron elicits on a personal level, although several of his predecessors’ policies caused their share of protests. “Obviously, five years ago, he came out of nowhere and transformed the political arena, and he surprised every single reporter in town,” said Roland Lescure, a parliamentary deputy from Macron’s party. “And I think people have kept a bit of resentment.”

The source of that resentment seems to be more a matter of tone than of policy, which Macron appears to realize. In the short amount of time he has devoted to this year’s election campaign, he has apologized for remarks that have offended many French people. But some of them have been difficult for voters to forget. In 2017, at the opening of Station F, a start-up incubator that was a fitting project for the “Start-Up Nation” he wanted France to become, he spoke about how in a train station one often encounters des gens qui ne sont rien—people who are nothing. (“He’s someone who cuts through the bullshit regularly, and has been perceived in France as being arrogant,” Lescure said.)

This perception was one major reason for the gilets jaunes uprising against his government in 2018 and 2019, a protest against a proposed carbon tax increase that turned into a vengeful, violent, and seemingly endless demonstration of the provinces against Paris, but perhaps against the hubris of Macron most of all. “People who are nothing” have had enough of Macron, and they are flirting with alternatives that the political establishment considers beyond the realm of respectability and decency but that nevertheless resonate with many ordinary voters, more than half of whom backed candidates from the far right or the far left in the first round of the vote.

None of these concerns has seemed to matter to Macron until now. He is the darling of the French financial elite and is close, for instance, to Bernard Arnault, the richest man in France and the chairman of the fashion conglomerate LVMH. In a strange move for a sitting president, Macron spoke at the reopening of La Samaritaine, LVMH’s new department store project, in June 2021. This year, on the last day of campaigning before the first round of voting, he stopped by a market in Neuilly-sur-Seine, on the northwest edge of Paris—one of the richest enclaves in the country—to greet voters. Macron promised to disrupt the way things were done, but he has come to be seen as the epitome of the establishment, and perhaps even its last bulwark.

But even in one of Europe’s most robust and generous welfare states, there are legitimate concerns about rising inequality. A study by the Institut des politiques publiques found that almost all French households have seen a small increase in their income, but the bottom 5 percent saw theirs decrease and the largest gains were among the rich. These inequalities are not only economic but social; education levels are some of the most unequal among OECD countries. This is partly why Macron has gained a reputation as le président des riches—a reputation that has not been helped by the recent revelations that his government has paid more than €2 billion to consulting firms such as McKinsey over the past five years for advice about everything from the Covid vaccines to pensions.3 When asked about Macron as the president of the rich, Lescure said that “facts don’t really matter” to Macron’s critics. He pointed to the general increase in incomes and falling unemployment rates. “But it has to be admitted that the perception is there.”

Macron’s economic program would not be so divisive if he had a positive vision to offer in other areas of French life. But on matters of crucial importance—climate, gender equality—France has seen little change from the president who vowed to “Make Our Planet Great Again.” Much of what he has to say about French society is taken from the far right. At a rally in Paris in early April, the only major event Macron’s campaign hosted before the first-round vote, he spoke of the dangers of extremism, especially on the far right. At that point Le Pen had risen in the polls to a degree that began to worry Macron’s advisers. “The danger of extremism has reached new heights because, in recent months and years, hatred and alternative truths have been normalized,” Macron said. But his administration has contributed, even unwittingly, to normalizing the same far right he condemns.

Since his election in 2017 Macron seems to have judged that the way to neutralize extremists like Le Pen, Zemmour, and the many who agree with them is to concede that there is a kernel of truth in what they are saying, especially about Islam and its compatibility with the French Republic, and yet somehow to acknowledge those issues in a positive way. But this has often only resulted in bringing bad-faith and toxic ideas more attention in the mainstream. One of the more embarrassing episodes of Macron’s presidency occurred in October 2019, when he found the time for a lengthy conversation with the far-right magazine Valeurs Actuelles. He appeared on the cover in a pensive pose with the following quote: “The failure of our model is combined with the current crisis of Islam.”

But these tactics—intended to reach new audiences—have not neutralized the far right at all; it has never been more popular, as the results of the April 10 vote make clear. If anything, Macron’s strategy—suggesting that the French social model, for instance, is in some way a “failure” or that Islam, an ancient religion, is in “crisis”—has made the far right look like it has valid arguments, which it defends more strongly than he ever could.

Macron’s government spent years preparing an “anti-separatism” law meant to fight Islamist extremism through increased security and police capacity, but also through new rules about “republicanism” in public life. Some version of this might have been an understandable response to a number of terror attacks: after all, Islamist terrorists have killed more than 230 people in France since 2015—a genuine national security concern. But the bill led many to be confused about what, exactly, the government’s target was—Islamism or Islam itself (here Macron’s interview with Valeurs Actuelles did him no favors). Macron’s interior minister, Gérald Darmanin, attacked Le Pen in a televised debate last year for being too “soft,” and also railed against the fact that “communitarian cuisine” like halal and kosher meats were separated from the rest of the food in supermarkets. The education minister, Jean-Michel Blanquer, has actively discouraged Muslim mothers who wear the headscarf from chaperoning school trips. Perhaps most embarrassing of all, Macron’s higher education minister, Frédérique Vidal, announced in 2021 a government crusade against islamo-gauchisme, or Islamo-leftism, in French universities, while simultaneously admitting to the press that she could not define the term. “Of course, islamo-gauchisme has no scientific definition,” she told the Journal du Dimanche in February 2021. “But it corresponds to the feelings of our fellow citizens.”

All of this put Macron in a weak position as he went into the election: he needed, and still needs, to show that he can be a palatable president for left-wing voters, but both his economic policies and his forays into identity politics have alienated them. After the first round, Mélenchon, who came in right behind Le Pen, urged his voters, many of whom loathe Macron, not to give “one single vote” to her in protest. And Macron has said, in an apparent concession to the left, that he would consider withdrawing his proposal to raise the retirement age from sixty-two to sixty-five.

But this may be too little too late. A distant campaign has failed to shake the image of Macron as secretive and more concerned with his own reputation than the well-being of France, which has allowed Le Pen to style herself—falsely—as not just a voice of strength but a voice of empathy and calm. “I will be the president of social harmony,” she said recently. It’s telling that Le Pen, who is now running for the third time, has changed tactics and done what Macron has refused to do: go from town to town and talk about the cost of living. This strategy may well pay off.

3.

In this election, more than just Macronism is at stake. Macron is favored to prevail against Le Pen in the second round on April 24. But around 60 percent of voters cast a ballot for a Euroskeptic candidate on the right or the left. Whoever wins will have a strong say on the future of the European Union.

At first glance, Macron’s pro-European stance since well before the war in Ukraine would seem to improve his chances for reelection. Since the beginning of his time in office, he has called for a stronger European Union and more investment in European “strategic autonomy”: the idea that the EU should be able to stand on its own without the support of the United States, especially in defense matters. In the days after the Russian invasion, headline after headline celebrated Europe’s unity. There was an almost uncanny level of celebration about this newfound spirit—built as it was on the deaths of thousands and the displacement of millions.

Officials close to Macron congratulated their own foresight. At a discussion panel hosted by a member of his cabinet a few days after the invasion, Jean-Louis Bourlanges, the head of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the French National Assembly, praised the Germans, who had recently agreed to increase defense spending, for finally listening to the French. “I told them you can’t stay in this situation where you are denying the geopolitical stakes of the European project,” he said. “[They] have to take on more responsibility. Macron has been suggesting this.”

The EU would appear to be moving in Macron’s direction. Last month, it ratified a “strategic compass,” which proposes a “quantum leap forward” in defense. By 2030, the EU will start building a “Rapid Deployment Capacity” with five thousand troops, and it will stage “live exercises on land and at sea.” (Frontex, the EU border patrol, which has been known to violently push back migrants, falls under a separate bureaucratic category.) This investment is intended to make Europe less reliant on the United States for its defense, and many hope that it will have a more cohesive identity and purpose.

On a practical level, much remains to be determined about how this autonomy will be achieved. First, there’s the question of France’s place in the EU itself. “France, in a way, is the biggest obstacle” to European defense, says Sven Biscop, head of the Europe in the World program at the Egmont Institute in Brussels. He notes that the French have tried to push for cooperation of forces, rather than their integration, keeping them separate even when European forces have to work together. “Why not make a European cyber command from the start, when we have the chance, or a European drone command?”

But what Europe does is in some ways bound by what France does. If Macron loses, the picture may look very different. Le Pen no longer calls for France to hold a referendum on EU membership, as she did in 2017. But much of her presidential manifesto, which includes ID checks at the French border and reducing French participation in the EU budget, would be a de facto “Frexit,” according to Le Monde. She calls for a “European Alliance of Nations” to gradually replace the European Union, and she would withdraw France from NATO’s integrated military command. She no longer openly talks about modeling herself on Putin, but her party was forced to destroy the 1.2 million pamphlets it had printed with a picture of her shaking his hand.

Her anti-European sentiments are shared to some degree by most of the candidates who came behind her in the polls. Zemmour campaigned for French sovereignty. Late last year, when the Arc de Triomphe was decorated with the EU flag to celebrate France’s six-month rotating presidency of the European Union, the Républicains’ presidential candidate, Valerie Pécresse, called for it to be taken down, claiming that it erased French identity.

Euroskepticism is not just a phenomenon of the right. Mélenchon shares this distrust of European institutions.4 At a recent rally in Les Lilas, northeast of Paris, electoral materials noted his party’s stance against common European defense. “This crisis is also a reminder that, militarily, Europe is subservient to NATO’s objectives. The expansionist policy of Putin’s regime cannot justify this state of affairs,” said a flyer. François Ruffin, a filmmaker and member of Mélenchon’s party, France Unbowed, in the National Assembly, concluded his remarks by saying that even if Mélenchon won, his goals would be impeded by lobbying groups, the European Commission, and the European Central Bank. Those institutions, he said, would have to ask for “mercy” from Mélenchon. The crowd cheered at this. It seemed that “Europe” remained synonymous with many of their criticisms of Macron—obscure, distant, a system that puts elite interests first.

Although the EU may be putting forth strong statements about the future of Europe and its autonomy, not all of these decisions are binding, as Biscop explains. The EU has been trying to “create a strong political framework that makes it increasingly difficult for the member states to do nothing” about defense. But it cannot force them to cooperate. “There is an obvious political pressure today. We have terrible images [of Ukraine] in the media and the whole population is watching and so it is normal to have a reaction,” says Martin Quencez, an analyst at the German Marshall Fund in Paris. Policymakers now speak about investing in the conflict. “In a year or two, where will they be and what will their policy priorities be?” he says. “We’ll see.”

4.

The French traditionally have had little love for Europe. “Remember when we lost the referendum on the European Constitution in 2005? People were not European,” François Bayrou, the Pau mayor and Macron ally, says. “They had the feeling that ‘Europe’ was only people who wanted to prevent them from living [the way they wanted to]. But Ukraine changes everything.” Would the people in Pau stop caring about what’s happening abroad if the war dragged on? “Think again,” says Bayrou.

The biggest agricultural cooperative in Pau makes two thirds of its annual profit in Ukraine and Russia. With dozens of people working [in Ukraine], that’s a lot of families. The globalized world is no longer a compartmentalized world.

He cited other companies in the area that were seeing their work affected by the war. Safran, an aeronautical company that supplied Ukraine and until recently Russia, had a factory nearby. The French oil and gas company Total, he noted, also has a large presence in Pau. The war in Ukraine, he said, was not far away at all.

But Alain Vaujany, a former high school principal who now works on creating international partnerships as a member of the city council, said that looking abroad was not really part of the local culture. Many of the city’s partnerships with foreign cities had ended during the Covid crisis. Still, he suggested, the people of Pau had a special affinity with the Ukrainians because the Béarn, the once-independent region in which the town is located, was annexed by France in 1620, just as Russia had done to Ukraine in the past and is trying to do again today.

At Macron’s event in Pau on March 15, the Palois (as the city’s residents are called) seemed mixed in their response to the European question. Cécile, who works in international development, said she thought that Macron’s engagement in Europe was a strength. Julien, a young man studying cybersecurity, who was voting for the first time, was more drawn to the candidate’s manner and presence: “I think he’s confident, he’s serious, and he [talks] without necessarily having a text in front of him.” Julien works part time advising the local governmental council, which, he worried, could come under indirect cyberattack.

Across the hall, Lucas, eighteen, was also keen to vote for the first time. He is in a preparatory class to study to be an engineer—he hoped to work in one of the defense companies near Pau. Asked if he felt European, he said that he felt “first of all French and especially Gersois because I come from the Gers,” the département next to Pau. He conceded that this made him “automatically French and European too, but that comes second.”

Afterward, Macron was at the local préfecture, talking to Putin. People had gathered; some news crews were waiting to see when he might come out. A woman walked by and complained that the poor in France were not getting the same kind of treatment as Ukrainian refugees.

Among those who were standing outside was Luba, a Ukrainian woman with a yellow coat and a blond bob who has been in Pau for about ten years, since she moved there after college to improve her French. When Russia attacked Ukraine on February 24, she said, she had stood outside the mayor’s office with her daughter. They decided that if they stayed until 8 PM, Kyiv wouldn’t fall. In the days following, she founded an organization called Vesna 64, named after the Ukrainian word for “spring” and the number of the local département. With other Ukrainians in the region, as well as Russians, she had sent medication, baby food, and other supplies to Ukraine. She was now helping to organize refugees coming to Pau. So far, forty-eight children and seventy adults had arrived. She was happy with the willingness of the Palois to pitch in.

While we waited, she got a phone call: a group of four refugees would be arriving the following Tuesday. She told the caller that she would be able to meet them at the train station. She wanted to be able to reassure them.

Macron didn’t emerge from the préfecture. “I had hoped that it would be in Pau, with this phone call, that war would end,” Luba texted the next morning. It remains to be seen if Macron’s other initiatives will be more successful.

—April 14, 2022

This Issue

May 12, 2022

Burkina Faso’s Master Builder

What Are You Looking At?

-

1

See James McAuley, “Who Does Éric Zemmour Speak For?,” The New York Review, January 13, 2022. ↩

-

2

“Volodymyr Zelensky in His Own Words,” The Economist, March 25, 2022. ↩

-

3

See Rym Momtaz and Elisa Braun, “Sluggish Coronavirus Vaccination Rollout Poses Risks for Macron,” Politico Europe, January 4, 2021. ↩

-

4

See Madeleine Schwartz, “Bike Lane to the Élysée,” The New York Review, March 24, 2022; and James McAuley, “A Failure of Imagination,” The New York Review, April 21, 2022. ↩