Why do certain experiences lodge in our memories while others—more triumphant perhaps, or more traumatic—leave barely a trace? In his memoir, Little Did I Know, the philosopher and cultural critic Stanley Cavell records an odd event from his childhood. His parents—his mother was a gifted pianist who played in vaudeville theaters and accompanied silent films, his father a Polish immigrant who worked in pawnshops and jewelry stores before the Depression—had embarked with Stanley, their only child, on the first of three failed attempts to establish a better life in Sacramento, returning each time, in defeat, to their home in Atlanta. Poking around a vacant lot behind a Sacramento gas station, Cavell, nine years old at the time, found a glass jar with a rusted lid punched with holes, presumably to keep fireflies from suffocating. “I unscrewed the cap,” Cavell recalls,

and filled the jar with one of each different thing or creature I came across in the field, a twig, crumbling leaves, assorted bugs, various kinds of stones, perhaps a marble, a gum or candy wrapper, a soda bottle cap, a piece of torn tennis ball, to which I added a penny and a duplicate stamp from my collection, enclosed in a folded envelope, which I found in my pocket.

After stowing the jar beneath a clump of trees, Cavell was surprised to hear “a faint low hum as if produced by the ground,” at a frequency he was convinced he alone could hear.

“What,” Cavell wonders, “keeps the memory of this small, isolated set of events coming back, perhaps every other year?” It’s a question that he doesn’t fully answer. The jar and its enigmatic contents may seem to suggest a time capsule or, with envelope and stamp, a message in a bottle to Cavell’s future self. “If I say now that I was burying my life,” he remarks, “perhaps to preserve it for some time in which it might be lived, or chosen, I need not imply that these are thoughts I could have formulated then.” But it’s hard not to see the buried jar with its mysterious hum as a metaphor for the subterranean workings of memory itself.

Unpacking such memories eventually acquired some urgency for Cavell. Both Little Did I Know (first published in 2010) and many of the twenty-five relatively short essays (including tributes to teachers and colleagues, reflections on psychoanalysis, and a substantial clutch of writings on music) gathered in the posthumous collection Here and There reflect the increasingly autobiographical turn in Cavell’s later work, as though getting such memories right might help elucidate his extraordinarily varied philosophical interests.

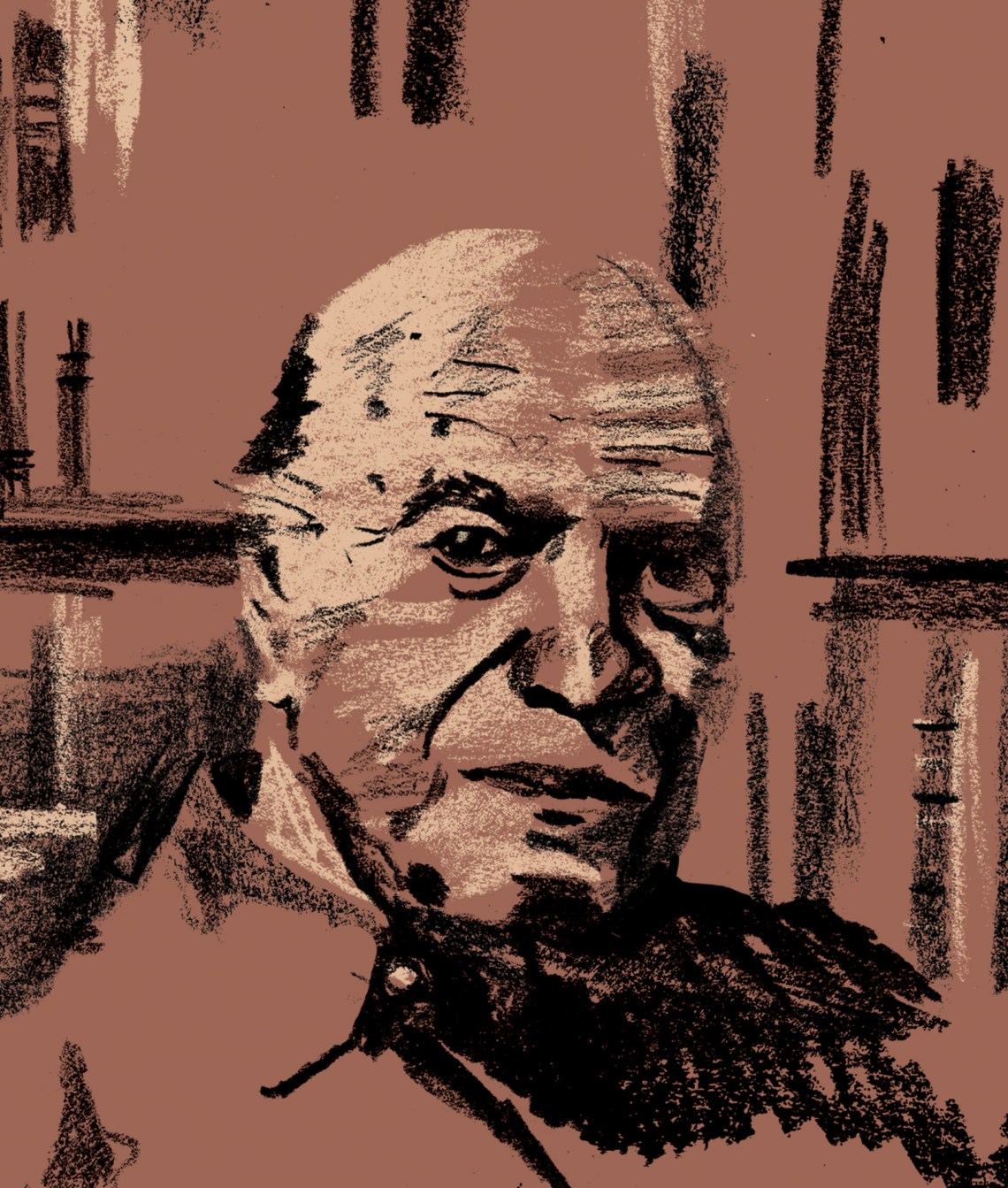

Cavell, who died in 2018, was the Walter M. Cabot Professor of Aesthetics and the General Theory of Value at Harvard from 1963 until his retirement in 1997. Despite belonging to one of the most prestigious philosophy departments in the world, he cultivated a posture of professional unease. “What I do,” he remarked in a retrospective essay in 1992, included in Here and There, “has sometimes been denied the title of philosophy, or deplored under that title.” Cavell published dazzling books on unorthodox philosophical subjects ranging from Shakespearean tragedy to Hollywood screwball comedies—a subset of which he identified, in Pursuits of Happiness (1981), as “comedies of remarriage,” in which women demand equal status with their husbands. Beginning with The Senses of Walden (1972), Cavell also sought to promote his fellow mavericks Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson—dismissed as intellectual lightweights among his professorial peers—as the towering founding figures of American philosophy. That Friedrich Nietzsche was “pervasively indebted” to Emerson was evidence enough, in Cavell’s view, of Emerson’s significance in modern philosophy.

The philosopher Richard Rorty called Cavell “the least defended, the gutsiest, the most vulnerable” of philosophy professors. “He sticks his neck out farther than any of the rest of us” in questioning the foundations of philosophy and the motivations of philosophers. Recalling “the old saw that philosophers kick up dust and then complain that they cannot see,” Rorty said that Cavell’s work asks:

What compels them to kick up all that dust?… Why do philosophers go in for skepticism? Why do they ask whether the table is really there, whether you might turn out to be a robot, whether you see what I see when we simultaneously remark the deep vermilion in the rose?

Cavell risked his reputation not only in his adventurous scholarship, but in his support of students demanding a black studies program at Harvard in 1969. Five years earlier, he had participated in the Freedom Summer drive for voting rights, teaching at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, which he called a “transfiguring moment in my experience.” He was also a cofounder of the Harvard Film Archive in 1979, at a time when the academic study of film had a low profile in American universities.

Advertisement

Born Stanley Goldstein in Atlanta in 1926—as a teenager he adopted an Anglicized version of his family’s Polish name of Kavelieruskii—Cavell resembled in certain ways his brilliant contemporaries William H. Gass and Susan Sontag. All three were trained in academic philosophy during the 1950s, the heyday of the rivalry between the more humanistic “continental” philosophy (centered in Germany and France) and the more scientific “analytic” philosophy in the US and Great Britain. All three came under the influence of “ordinary language” philosophy, the conviction, derived from the Oxford philosopher J.L. Austin and the later phase of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s work, that a promising way to address such traditional philosophical problems as the nature of justice or how we know that another person is in pain is to examine the ways in which we habitually talk about such things. Gass studied briefly with Wittgenstein at Cornell; Sontag attended Austin’s lectures at Oxford; Cavell described working with Austin at Harvard as a “conversion experience.”

A deeper bond is that all three aspiring philosophers were practicing artists. Gass and Sontag wrote ambitious fiction alongside their unorthodox philosophical treatments of, say, the color blue (Gass) or photography (Sontag). Cavell, by contrast, tried to bring the arts into philosophy, not only as a subject but as a mode of writing. “I have wished to understand philosophy not as a set of problems but as a set of texts,” he wrote on the opening page of his magisterial The Claim of Reason, a book that incorporates much of his Ph.D. dissertation on Wittgenstein. In treating Wittgenstein and Austin, Emerson and Thoreau, Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger more as “creative thinker[s]” than as solvers of problems, Cavell acknowledged, dryly, that “both historians and non-historians of the subject are given to suppose otherwise.”

Music, which he considered “as old among my cultural practices as reading words or telling time,” was the art form Cavell knew best, even as his own musical life was laced with trauma: he believed that his mother had given up a concert career to raise him, and the piano lessons he took as a child were interrupted (as he revealed in Little Did I Know) when he was sexually molested by a male teacher. As a teenager, he gravitated to the clarinet and saxophone, playing in swing bands to make money. He enrolled at Berkeley at sixteen to study music, then pursued a degree in composition at Juilliard, submitting with his application a clarinet sonata and incidental music for a campus production of King Lear.

Changing his name—“declaring the search for a life I could want, not merely endure, in America”—was one step toward independence; another was abandoning music. His original work “had its moments,” he realized, “but on the whole I did not love it; it said next to nothing I could, or wished to, believe.” In what he called “the major intellectual, or spiritual, crisis of my life,” he decided that his career as a musician was over1:

And there came a late afternoon, not more than six or seven weeks after beginning classes for the spring semester, an ending of the Juilliard school day still turning dark by six o’clock, on which I formed the thought—I remember marking the moment by staring upward, as I was standing on a crowded Broadway bus headed downtown after a late afternoon class, at the chipped and scorched plastic cover of one in the two rows of lights extending the length of the sides of the low ceiling of the bus—that I would not be returning to Juilliard.

Downtown meant the movie theaters where Cavell was discovering an art form he could believe in. The bus ride as he describes it has a distinctly cinematic feel, like the bus that represents freedom for a runaway bride in It Happened One Night, one of the films about personal declarations of independence that he discussed in Pursuits of Happiness.

After leaving Juilliard “a lost young musician,” and combing through Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis to try to find a way out of his emotional crisis, Cavell returned to California to resume his studies before entering graduate school in philosophy at Harvard. In the spring of 1955, he attended Austin’s seminar on excuses (the basis for Austin’s celebrated essay “A Plea for Excuses”). Listening to Austin, who happened to be an amateur violinist, tease out “the difference between doing something by mistake and by accident and the difference between a sheer or mere or pure or simple mistake or accident,” Cavell experienced “a sense of revelation.”2 The intellectual exercises in Austin’s classes, meant to reveal the precision built into ordinary spoken language, “acquired the seriousness and playfulness—the continuous mutuality—that I had counted on in musical performance.”

Advertisement

The ways that ordinary language can shed light on our everyday lives struck Cavell as having a particular relevance for the arts. The music he had composed for a Berkeley production of King Lear paled for him when compared to the expressive impact of Shakespeare’s text, with Lear’s shocking demand for proof of his daughters’ love. The result was Cavell’s landmark essay “The Avoidance of Love: A Reading of King Lear.” Cavell argued that certainty of the kind that Lear, a mouthpiece for skepticism, asks of his daughters, or Othello of his wife, is not available in human affairs, and that demands for certainty lead inevitably to tragedy. As an alternative, Cavell offered what he called acknowledgment, our everyday, trusting substitute for certainty. He later summed up the distinction in an aphorism: “The eye teaches skepticism; the eyelid teaches faith.”

In essays on six of Shakespeare’s plays, collected in Disowning Knowledge (1987), Cavell took his promptings from the words on the page, puzzling out the various ways in which Shakespeare examined doubt and certainty. Cavell insisted that he was not enlisting the plays as illustrations of familiar philosophical ideas. “The misunderstanding of my attitude that most concerned me,” he wrote,

was to take my project as the application of some philosophically independent problematic of skepticism to a fragmentary parade of Shakespearean texts, impressing those texts into the service of illustrating philosophical conclusions known in advance.

In Cavell’s experience, this was precisely how philosophers tended to approach works of art. In Here and There, he laments that the questions that “the Anglo-American dispensation of philosophy…characteristically addresses to artistic entities neither arise from nor are answered by passages of interpretation of those entities.” In Little Did I Know, he singles out John Dewey’s Art as Experience as a typical example of aesthetic cluelessness, asking why “it so often seems that philosophical treatments of the fact and of objects of art…were so often less interesting, philosophically and aesthetically, than the objects they were about.” The best criticism should aspire to the status of art, Cavell claimed: “Describing one’s experience of art is itself a form of art.”

It was in the best film journalism (James Agee, André Bazin) and in the New Criticism that Cavell found the interpretive energies he was looking for. What literary critics like William Empson and Kenneth Burke were doing, he wrote, “remained to my mind incomparably more interesting, and indeed intellectually more accurate, than the competing provisions of analytical philosophy.” In a foreword (included in Here and There) to a new edition of Northrop Frye’s A Natural Perspective: The Development of Shakespearean Comedy and Romance, a decisive influence on his own work on comedies of remarriage, Cavell recounts his first encounter with Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism, and his conviction—ultimately disappointed—that Frye’s brilliant work on literary genres and modes would “have some unanticipated perspective on those presentations of writing held to do the work of philosophy.”

Cavell’s writing about art is grounded in his sheer gratitude for its existence. Calling it “a fruitful aesthetic tip,” he quoted Wittgenstein’s injunction: “Don’t take it as a matter of course, but as a remarkable fact, that pictures and fictitious narratives give us pleasure, occupy our minds.” In an early essay on atonal music, he stressed our intimacy with works of art:

Objects of art not merely interest and absorb, they move us; we are not merely involved with them, but concerned with them, and care about them; we treat them in special ways, invest them with a value which normal people otherwise reserve only for other people—and with the same kind of scorn and outrage. They mean something to us, not just the way statements do, but the way people do.

Cavell rarely succumbed to scorn. When he did, as in his withering assessment of a scene in the film version of Goodbye, Columbus, the context—in this case the use of slow motion—was often one of celebration:

It may not have needed Leni Riefenstahl to discover the sheer objective beauty in drifting a diver through thin air, but her combination of that with a series of cuts syncopated on the rising arc of many dives, against the sun, took inspiration…. You’d think everybody would have the trick in his bag by now: for a fast touch of lyricism, throw in a slow-motion shot of a body in free fall. But as recently as Goodbye Columbus, the trick was blown: we are given slow motion of Ali MacGraw swimming. But ordinary swimming is already in slow motion, and to slow it further and indiscriminately only thickens it. It’s about the only thing you can do to good swimming to make it ugly.

Cavell wrote about film, theater, television, literature, and photography. Only rarely did he write about music, the art form he knew best. And then—after twenty years in which, as he put it, he “avoided the issue,” presumably because of the trauma associated with quitting Juilliard—he suddenly took it up again. “The group [of texts] whose emergence most surprised me,” he wrote in a draft preface for Here and There in 2001, when he had tentatively selected most of the pieces included in the volume,3 “is that of the four pieces on music.” These essays (a fifth was added later) are short but they are not slight. They aim to be “proposals,” “alternative routes of response” and “suggested line[s] of investigation” for nothing less than a new philosophy of music, “a way to envision what a philosophy of music should be, one which is itself illuminated by musical procedure.”

What it shouldn’t be, Cavell makes clear, is a philosophy that replicates the weird split between math and metaphysics, close technical analysis and broad cultural or ideological background, that one finds in too much writing about music, “as though music has never quite become one of the facts of life.” Having spent so many years listening for shifts of tone and pitch in ordinary language, Cavell found inspiration in Wittgenstein’s remark, quoted repeatedly in Here and There, that “understanding a sentence is much more akin to understanding a theme in music than one may think.”

Cavell is particularly impatient with Theodor Adorno’s work, which he finds insufficiently responsive to actual musical experience. He concedes that Adorno is, “like it or not, the thinker of his generation, extending to the present, who has most successfully made a claim to have presented a philosophy of music,” but finds Adorno’s claims about particular pieces unconvincing. He is puzzled by Adorno’s histrionic assertion, for example, that the first movement of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony combines in some unspecified way a sense of “constricted breathing” with the movement of “a coffin in a slow cortège.” How exactly, Cavell asks, “does the connection of a difficulty in breathing with the gait of a funeral march capture the experience” of listening to Mahler’s music?

In order to develop a satisfactory philosophy of music, Cavell remarks, “musicians and philosophers will have to spend considerably more time together than they have become used to.” He resists any philosophical intervention that precedes actually listening to the music, whether it is one of Adorno’s sweeping generalizations about Schoenberg (“the decline of art in a false order is itself false”) or the musicologist Peter Kivy’s claim that unless one is familiar with Descartes’s theory of the emotions, Mozart’s Idomeneo will seem “out of tune with our psychological reality.” To Cavell, this is no more useful than researching the four humors in order to understand the emotions expressed in Othello. Listening to a quartet of voices from Mozart’s opera, Cavell comments, “Surely I am not alone in finding its projection of isolation even in the grip of common suffering…to be drop-dead convincing.” To Cavell’s ear, a particular “rage aria to end all rages” in Idomeneo is actually “far ahead of” Descartes in the way it links, by an unexpected plunge below the expected tonic, the emotions of rage and melancholy.

As he explored new ways of thinking about music and the other arts, Cavell was also experimenting with alternative ways of writing. In his later prose, two voices, two styles, are seemingly in conflict. One is a cascading, self-referential river of clauses, most notoriously in the nearly page-long question that opens The Claim of Reason:

If not at the beginning of Wittgenstein’s later philosophy, since what starts philosophy is no more to be known at the outset than how to make an end of it; and if not at the opening of Philosophical Investigations, since its opening is not to be confused with the starting of the philosophy it expresses, and since the terms in which that opening might be understood can hardly be given along with the opening itself; and if we acknowledge…

In Little Did I Know, with its time-shuttling weave of diary entries alternating with deep dives into the remembered past, Cavell often adopts this almost mannered voice, borrowing his serpentine rhythms from Henry James and Marcel Proust.

But Cavell has a countering (or perhaps contrapuntal) voice, which aspires to the abruptness of aphorism. A talent for the witty aside had always been a resource in his writing, as when he remarked in Pursuits of Happiness that “a willingness for marriage entails a certain willingness for bickering.” In his later writing, aphorism becomes an end in itself. There is a moment in Little Did I Know, dating from the summer of 1972, when Cavell, inspired by the fragmentary writings—and the Provençal landscape—of the poet René Char, tries his hand for “ten days of quite deliberate departure and direction in my writing.” The resulting aphorisms, reproduced in Little Did I Know, pointed a way forward. “Advice on being human,” he wrote. “Do not stomach what you have no taste for, for you will develop the taste.” Or: “Five senses and just one world. The odds were fair enough.”

A philosophy built entirely of aphorisms is what Cavell found in his two major models of philosophical style, Wittgenstein and Emerson. For both thinkers, a turn toward the aphoristic coincided with a rejection of systematic aspirations. Cavell asks readers “to recall Emerson’s and Wittgenstein’s relation, in their fashionings of discontinuity, to the medium of philosophy as aphorism, in counterpoise to its medium as system.” In an impressive essay on collecting titled “The World as Things,” included in Here and There, Cavell relates Emerson’s interest in natural history museums to the magpie assemblages—cullings from personal journals, quotations from stray reading, fleeting insights—that formed his essays.

Cavell offers a fresh interpretation of Emerson’s visit to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris in July 1833, when Emerson (as many biographers have pointed out) was overwhelmed by the “bewildering series of animated forms” on display, the “beautiful collection” of birds in their “fancy-colored vests,” the scorpions with which he felt “an occult relation.” Walking through the zoo and noting the animals “that Adam named or Noah preserved,” he said to himself, “I will be a naturalist.” What Emerson took from this revelatory visit, in Cavell’s view, was not some simmering conflict between scientist and philosopher, but a confirmation of his instincts as a writer. The “beautiful collection” of birds matches “the way we are to see [Emerson’s] sentences hang or perch together.” According to Cavell’s reading, “Every Emersonian sentence [is] a self-standing topic sentence of the essay in which it appears,” while Emerson’s paragraphs are “bundles or collections that may be moved.”

Cavell’s observation registers the oddly percussive and additive quality of Emerson’s prose in essays like “Self-Reliance,” as well as the numbered entries in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. But it also gestures toward how Cavell wanted his own late writings to be received. In “The World as Things,” he describes a sense of looking at the world, as well as writing about it, as “aggregation and juxtaposition.”

One thinks in this regard of the buried jar filled with “one of each different thing or creature.” In Little Did I Know, Cavell connects that moment with a radio announcement he heard, around the same time, that the kidnapper of the Lindbergh baby had been executed. The radio emitted a hum that Cavell assumed was the sound of the electric chair. Six decades later, he found himself “teaching a course on opera and film [and] describing the Overture of The Marriage of Figaro as expressing the hum of the world, specifically the restlessness of the people of the world.”

Cavell provides no explicit linkage among these instances. He offers them for inspection, like the exotic hummingbirds and parrots on display in the Jardin des Plantes. What comes across most powerfully, in this and other passages of “aggregation and juxtaposition” in Little Did I Know and Here and There, is Cavell’s attentive listening, throughout his long and distinguished career, for what one might call the hum of humanity.

-

1

The phrase is from “Reflections on Wallace Stevens at Mount Holyoke.” The essay was written at my invitation, for a 2003 symposium commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the wartime gatherings, known as “Pontigny-en-Amérique,” when European artists and intellectuals in exile met with their American counterparts on the Mount Holyoke College campus. Knowing that Cavell had studied with the composer Roger Sessions, one of the original Pontigny participants, I invited him to draw on his own memories of Sessions, which he charmingly did in recalling a disaster averted when, with Sessions conducting his first opera, The Trial of Lucullus, set to a Bertolt Brecht text, Cavell “overcame a crisis in the middle of the opening night’s performance, transposing an English horn solo on the clarinet when the English horn suddenly broke down.” Cavell’s essay on Stevens, another Pontigny participant, turns on the theme of anticipation in Stevens’s work, with a nod toward Thoreau. Stevens’s famous poem “Anecdote of the Jar” is in the background, I believe, of his own anecdote of a buried jar. ↩

-

2

A famous footnote from “A Plea for Excuses” turns on this distinction: “You have a donkey, so have I, and they graze in the same field. The day comes when I conceive a dislike for mine. I go to shoot it, draw a bead on it, fire: the brute falls in its tracks. I inspect the victim, and find to my horror that it is your donkey. I appear on your doorstep with the remains and say—what? ‘I say, old sport, I’m awfully sorry, etc., I’ve shot your donkey by accident’? Or ‘by mistake’? Then again, I go to shoot my donkey as before, draw a bead on it, fire—but as I do so, the beasts move, and to my horror yours falls. Again the scene on the doorstep—what do I say? ‘By mistake’? Or ‘by accident’?” ↩

-

3

The editors added a few “thematically congenial pieces written after 2001” while omitting texts Cavell subsequently published in other books. ↩