On New Year’s Day, I went to a bookstore in Cheonan, South Korea, to buy a wall map of the country. The label said, simply, “Map of Korea,” so when I got home and unfolded it, I was surprised to see that it showed both North and South—the entire peninsula and its hundreds of surrounding islands. The wars of the twentieth century had turned one country into two, mutually cordoned off and inaccessible; South Koreans are not permitted to visit North Korea, or even its websites, and vice versa. My new map felt strangely aspirational. The armored boundary between the two Koreas, the Demilitarized Zone that meanders along the 38th parallel, was just a thin, red dotted line, hard to make out.

That red line was first drawn at the end of World War II, when Korea was freed after decades of Japanese rule and cracked into Soviet and American halves. In 1948 the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was established in the North and the Republic of Korea in the South. The Great Powers installed authoritarian leaders to their liking, giving ordinary people little say. Leftists in the south of the peninsula formed underground communes and waged guerrilla struggles. Tens of thousands were massacred by US-backed South Korean forces.

In 1950 troops from Soviet-controlled North Korea crossed into the US-controlled South. The Chinese army later entered the war to support the North, and the US worked through a nascent UN to recruit infantrymen from fifteen other countries. (Officially, President Truman did not ask Congress for a war declaration, calling UN intervention in support of the South a “police action.”) Many Koreans found themselves fighting for one side or the other simply by chance. In the three years that followed, some four million people, most of them civilians, were killed. Millions more were injured or separated from their families, and the landscape was razed. The Korean War ended in a stalemate and an armistice that was meant to be temporary.

This was nearly seventy years ago. There is no longer active warfare on the peninsula (despite the occasional skirmish, rocket launch, and military drill), but neither is there a peace treaty. This fragile détente is held in place by an extraordinary buildup of arms, some of which are American. Nearly 30,000 US troops are still stationed in South Korea, ostensibly to defend it in the event of another invasion.

The Korean War was “the war that was not a war,” writes Monica Kim in The Interrogation Rooms of the Korean War: The Untold History. Kim, a Korean American historian at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, delves into a large archive of prisoner-of-war case files recently declassified by the US. She also draws on memoirs in English and Korean, interviews, even petitions written in blood. What results is a composite tale of the hundreds of thousands of POWs—rank-and-file soldiers and “civilian internees”—who were captured and held in sprawling, miserable camps on both sides of the 38th parallel.

For Kim, the newly revealed stories of these POWs help us understand the Korean War as an intimate civil conflict, not just a proxy battle between superpowers. In POW camps and interrogation rooms on the North–South border, soldiers and civilians were subjected to constant questioning. But the prisoners’ allegiances were, more than anything, a matter of survival. Just as on my wall map, the divide between the Korean people was, and is, imposed and often thin.

Two primary archives ground Kim’s research: investigation reports from the largest POW camp run by the US and UN, and files of more than one thousand US POWs who were interrogated by the US Counterintelligence Corps after returning from Chinese and North Korean camps. Reading through these documents, Kim finds time and again that loyalties were blurry. There was no intrinsic difference between a North Korean and a South Korean or a Korean leftist and a Korean rightist—or, for that matter, a Korean soldier and a Korean civilian.

Kim begins the book with the story of Oh Se-hui, who, in October 1950, was twenty years old and “making his way back to his home” in southern Korea, after serving in the North Korean army. Knowing that he would encounter North Korean, South Korean, and UN forces on his long journey, “he had stashed away four different pieces of paper in strategic places on his body”—each proof of a different affiliation. Stopped on a road by South Korean troops, he convinced them that he was not a soldier or a guerrilla. They took him as a prisoner of war.

Both sides of the conflict wanted not only to get information but also to promote their cold war ideology. They used coercion to prove the superiority of their cause. Americans and their allies interrogated South Koreans as well as North Korean and Chinese soldiers. Across the border, the North Koreans and Chinese questioned Americans, UN forces, and South and North Koreans. Where “no category—whether refugee, POW, anti-Communist, Communist—was stable,” Kim writes, every prisoner became a target of persuasion.

Advertisement

Camp Number 1 on Geoje Island (each camp had a number) was the largest run by the US and UN Command. At its peak, it held 170,000 people, segregated by nation, ideology, and gender, including women and children who were “suspected of being spies.” Truman’s Psychological Strategy Board saw interrogation as a form of counterinsurgency. There were, in addition to repeated interviews, film screenings and group discussions.

North of the 38th parallel was Camp Number 5, the largest camp operated by China and North Korea—though still much smaller than Camp Number 1—where prisoners were put in homes that had been evacuated along the Yalu River. In early 1951 the Chinese military began subjecting these POWs to intensive political education, including on “American plans for world domination; how capitalism got started and why it should be stopped.” Every day, the prisoners attended mandatory lectures and study groups.

In large camps like the one on Geoje, officials interviewed, examined, and photographed every POW upon entry. US and South Korean soldiers divided them into numbered compounds and summoned them for questioning—sometimes inside, sometimes outside; sometimes peacefully, sometimes under duress. In one (possibly staged) photo taken at a camp in Gurijae, which Kim found in the National Archives, a young Korean woman sits next to a helmeted South Korean soldier at an outdoor table, an expanse of dirt and fencing behind them. He looks at her and takes notes with a fountain pen; she holds up a document. “A communist woman leader, aged 20, formerly a student in Pusan,” the caption reads.

The US (representing South Korea and UN allies), China, and North Korea began to discuss a cease-fire early on, in the summer of 1951, but the parties could not agree on what to do with the people held across enemy lines. Prisoners of war had always been a feature of fighting, but now an expanded regime of international law dictated how they should be treated—and the cold war made the US less willing to follow the rules. Under the 1949 Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, every prisoner was supposed to be returned to his country of origin. But where was home for a North Korean who had fought for the South, or a young man from southern Korea whose family ended up north of the 38th parallel?

Yi Chong-gyu was a Christian teenager forced to join the North Korean army a few months into the war. After Yi’s unit was repelled by General MacArthur’s Incheon Landing in September 1950, he was captured by South Korean soldiers. They “took him aside for interrogation and asked him to recite the Lord’s Prayer,” Kim writes, to prove his (implicitly anti-Communist) religiosity and thus gain a kind of refugee status. When he did, they spared his life and took him to Geoje Island.

The interrogators were themselves often unsettled in their views and uncomfortable with their orders. Many of the US soldiers tasked with examining Korean prisoners were Japanese American. Officials assumed that they could communicate with Korean captives who had been required to use Japanese during the colonial period. Many of these Japanese Americans had just emerged from World War II internment camps, yet were expected to smoothly transition from captive to patriotic captor. The interrogators, not unlike the prisoners they interrogated, were forced to play a part, Kim observes. North Korean POWs were pressured to switch sides, and South Koreans were pressured to prove their fidelity. Everyone was cast in a role of self-justification.

One such interrogator was Sam Miyamoto, a California-born Japanese American whose family had been imprisoned in an internment camp in Poston, Arizona, in 1942. The following year, the Miyamotos were directed to board “the SS Gripsholm as parties to a POW/hostage exchange, where Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans were exchanged for white American businessmen, journalists, and missionaries,” Kim writes. Miyamoto, then a teenager, witnessed the devastation of Allied bombing in Tokyo and Hiroshima. He was effectively stateless in Japan, pawned off by the US but not legally Japanese, and thus unable to register for school.

In 1949 Miyamoto managed to secure a return to the US to attend UCLA. From there, he applied for a transfer to UC Berkeley to study law and attempted to put the indignities of internment behind him. But in that unlucky interval of disenrollment, he was drafted, trained as a military linguist, and sent to serve in the Korean War. Miyamoto was assigned to Geoje Island—his second prisoner camp, his second war. In an interview with Kim, he recalls telling his Korean prisoners, “I’m here because I was ordered to come here. I didn’t come here by choice.”

Advertisement

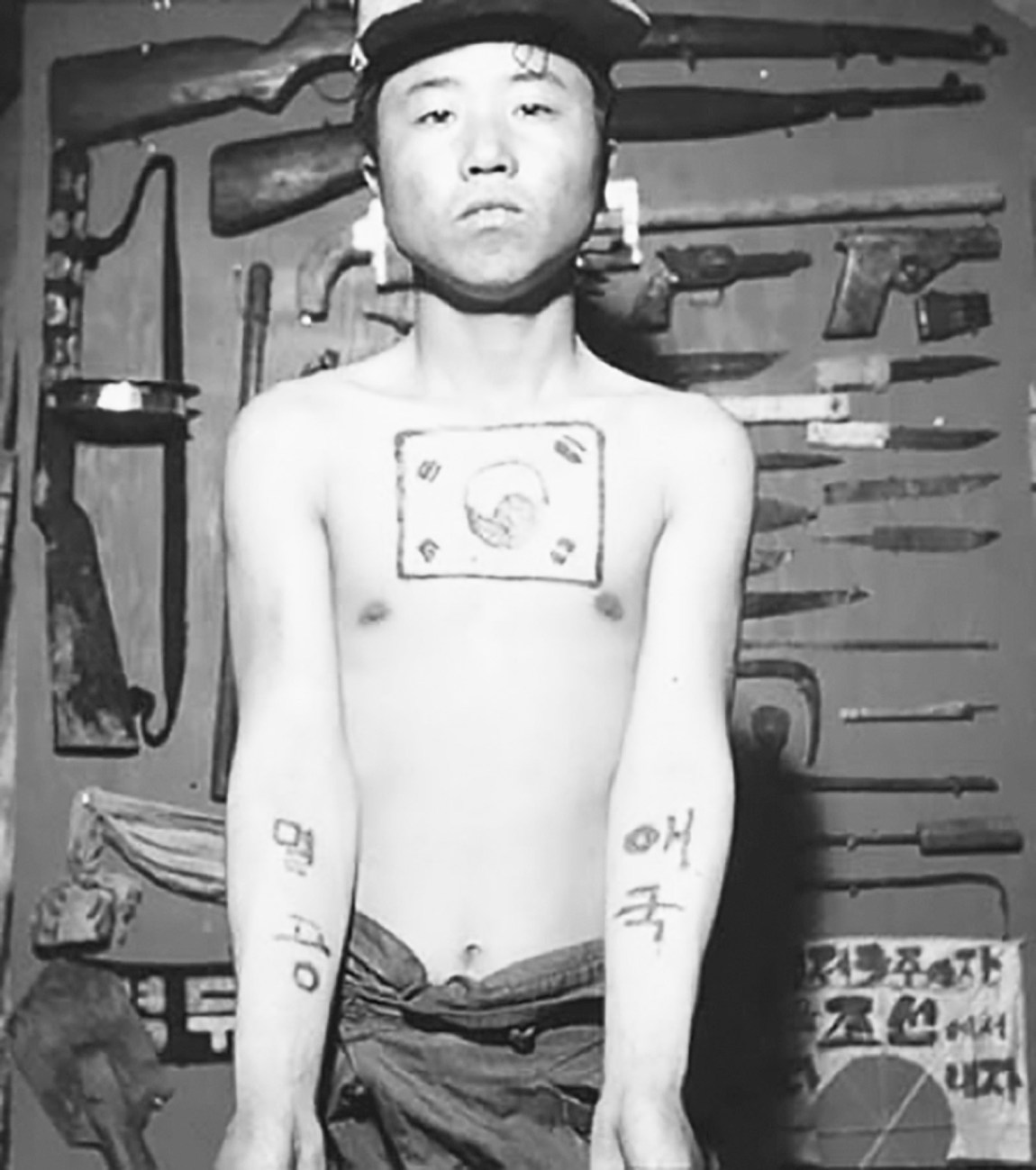

Many Korean POWs in UN camps like Geoje felt similarly misplaced. They told their captors that they were anti-Communist—maybe sincerely, maybe as a gambit—then took extreme steps to prove their fealty to Washington and Seoul. They tattooed South Korean flags on their torsos and sent officials petitions for release that were written in their own blood. Kim locates one of these petitions in the National Archives (kept in the same climate-controlled storage room as Jackie Kennedy’s bloodstained Chanel suit): “We are anti-communist young men. Let’s have discharge, so that we may be able to go front line.” Chinese anti-Communist soldiers acted out similar blood rituals, to convince the US to send them to Taiwan.

Before the Korean War, the US had vowed to abide by the Geneva Conventions. Yet when cease-fire negotiations began at the border between the two Koreas, the Truman administration refused to repatriate North Korean and Chinese prisoners as a matter of course. The US Psychological Strategy Board recommended a policy of “voluntary repatriation,” or letting POWs choose where to return. If, in the process of interrogation, some Korean Communists could be convinced to choose South over North Korea, Kim writes, it would “validate the US project of liberation through military occupation in the south.” Behind this strategy was National Security Council Paper 68 (1950), the founding document of the cold war, which called for “a more rapid build-up of political, economic, and military strength…to resist Soviet expansion” around the world. Korea was the testing ground for an emerging US strategy: a permanent battle for hearts and minds—and a permanent network of global bases—in the name of liberal democracy.

President Syngman Rhee, Washington’s man in Seoul, was sympathetic toward anti-Communist POWs and eager to incorporate them into his new police state. He even approved the release of 25,000 such soldiers from multiple UN camps without first consulting the Americans. “These Korean POWs did not simply vanish into thin air,” Kim writes. Many belonged to the rightist youth groups that had collaborated with the US military’s Counterintelligence Corps and the South Korean army before the Korean War—and continued to do their work.1 This form of “anti-Communist fascist mass organization,” Kim explains, held a “monopoly of violence in post-1945 Korea.”

In the Geoje camp, pro-Communist Koreans and Chinese also agitated for political recognition. Their “single, most important demand” was that the US military stop “repatriation screening,” Kim writes. In 1952 a group of these prisoners famously took hostage an American camp commander, Brigadier General Francis Dodd, to publicize the violation of their right to mandatory repatriation under the Geneva Conventions. The commander would “not be harmed if P[O]W problems are resolved,” the prisoners’ banner read. Western news readers reacted with fear and fascination to these brazen “reds,” but Dodd later reported that the worst he suffered was a broken fountain pen. The hostage-takers soon released him, on the condition that the US and UN agree to recognize them as representatives of the North Korean and Chinese POWs.

“In the days following Dodd’s release,” Kim writes, “the US Army launched the longest investigation of a POW-related incident conducted during the Korean War,” resulting in a five-hundred-page case file of interrogation transcripts and witness statements. Several weeks later, American paratroopers used “tanks, tear gas, grenades, and flamethrowers” to storm the camp. Thirty-five people were killed.

In July 1953 the UN Command signed an armistice with North Korea and China, and both sides began to clear out their camps. Despite all parties’ investments in propaganda and loyalty tests, prisoners largely chose to return home: 99 percent of Americans, 96 percent of South Koreans, and 91 percent of North Koreans. The exception were the Chinese, only 33 percent of whom opted for mainland China; the rest went to Taiwan. The Chinese were dealing with the aftermath of their own civil war.

Prisoners made their choices in a final set of interrogation rooms that were erected along the 38th parallel at the end of the Korean War. Groups of POWs were led into a holding area, then brought, one by one, into a UN “explanation booth,” a large tent. There, each POW was interviewed by a panel of officials from “neutral nations” and allowed to voice his desire: repatriation or non-repatriation. Earlier in the war, when the US had demanded a system of voluntary repatriation, India had devised a third-country compromise: POWs could choose to be sent home, into enemy territory, or somewhere else altogether. Seventy-six Korean POWs opted for a third country and were eventually settled in India, Brazil, Argentina, or Mexico.

Twenty-one American POWs, meanwhile, made the startling choice to stay behind Communist lines. This group included Clarence Adams, an African American who grew up in Memphis, under what he called “these cruel slave laws of the southern states.” In Communist Camp Number 5 on the Yalu River, Adams’s Chinese captors had let him manage the prison library and engaged him in a Communist study group; his white countrymen, meanwhile, called him “nigger.”2 After Adams settled in China, he attended college, married a professor of Russian, and recorded broadcasts that encouraged Black soldiers in the Vietnam War to resist American empire. But in 1966 he and his wife and two children returned to the US, to escape the Cultural Revolution. Adams was interrogated at length, but without incident, by the House Un-American Activities Committee and later opened several Chinese restaurants in his hometown.

Through the accounts of men like Miyamoto and Adams, Kim presents a “bottom-up,” people-centered history of the first hot war of the cold war. Her book catalogs the torn, often arbitrary allegiances of the Korean people—like so many people split apart by mass violence. In the case of the Koreas, though, that divide has only hardened since the 1950s. Today, stockpiles of missiles and large standing armies sit in wait on either side of the Demilitarized Zone.3 Families are estranged across the border. Yet the postcolonial vision of coexistence and exchange, if not unification, persists.

In the US, this vision was, however ironically, sharpened by President Trump’s volatile engagement with North Korea. Two years into his term, progressive members of Congress, including California representatives Ro Khanna and Barbara Lee and New York representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, introduced House Resolution 152, “calling for a formal end of the Korean war”—a peace treaty to replace the armistice. The bill acknowledges that, as Kim’s history of interrogation suggests, the war was muddier and less rigid in its dividing lines than Americans have always assumed. Among the lead sponsors of the bill was a first-term congressman from New Jersey, a “proud son of Korean immigrants” who spoke of bringing “peace to the Korean peninsula.” His name was Andy Kim, and his sister, Monica, had just published an especially relevant book.

-

1

Kim notes that Kim Du-han, a member of one such group and a notorious murderer, became Rhee’s bodyguard, then a member of the National Assembly. ↩

-

2

See Clarence Adams, An American Dream: The Life of an African American Soldier and POW Who Spent Twelve Years in Communist China, edited by Della Adams and Lewis H. Carlson (University of Massachusetts Press, 2007). ↩

-

3

Kim’s book contributes to a growing literature on the international reverberations of the Korean War. The Oberlin historian Sheila Miyoshi Jager examines the effect of the war on Mao Zedong and the emerging Chinese state in Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea (Norton, 2013). Tessa Morris-Suzuki, of the Australian National University, collects the wartime views of people in Mongolia, Manchuria, Okinawa, and Japan (including the improbable journey of the only Japanese POW) in her edited volume The Korean War in Asia: A Hidden History (Rowman and Littlefield, 2018). And David Cheng Chang’s The Hijacked War: The Story of Chinese POWs in the Korean War (Stanford University Press, 2019), a complement to Kim’s book, draws on interrogation records and extensive, multilingual oral histories to follow the winding experiences, and allegiances, of prisoners connected to both the Chinese mainland and Taiwan. ↩