There’s a diagram of the Internet that I show my students every semester. It was drawn in December 1969 and features four circles, four boxes, and four lines. The circles represent four institutions—UC Santa Barbara, UCLA, the University of Utah, and the Stanford Research Institute—while the boxes represent giant mainframe computers on their campuses. Those four machines, the dedicated long-distance phone lines connecting them to one another, and the “interface message processors”—computers dedicated to the task of routing information across the network—represented the entirety of the Internet in 1969.

The usual history of the Internet begins with this diagram. It’s a history that finds the Internet’s roots in the US Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, which financed those interface message processors, and that emphasizes the importance of academic computing in the 1970s and 1980s, before a commercial boom aided by Sir Tim Berners-Lee’s creation of the World Wide Web in 1989. The Web, initially a medium for scientific publishing and collaboration, made publishing online vastly easier by allowing users to embed images within text and to provide easy-to-follow links between different documents. This leap in usability turned the Internet from an academic curiosity into the dominant media and communication infrastructure of our time.

This standard history is well documented; it was passed around the early Internet in ASCII text files and has been enshrined in thousands of webpages, introductory chapters, and Wikipedia articles. It is accurate yet also deeply incomplete, as Kevin Driscoll argues in his new book, The Modem World. Driscoll, a professor of media studies at the University of Virginia, is part of a group of historians challenging the dominant account of the Internet’s evolution and, in the process, questioning whose values and motivations have shaped its development.

In that sense, Driscoll’s book can be read alongside two others. Joy Rankin’s A People’s History of Computing in the United States (2018) centers on the role of computing in K–12 schools rather than universities. Eden Medina’s Cybernetic Revolutionaries (2011) reaches back to Salvador Allende’s Chile to unearth techno-utopian ideas—especially Project Cybersyn, a nationwide computer system meant to help manage Chile’s economy—that have resurfaced in discussions of surveillance, artificial intelligence, and smart cities. Throughout these books is the reminder that the ideas underlying our contemporary digital environment have decades-old precedents, and that examining their histories can give us insights into current debates.

Driscoll’s previous book, Minitel: Welcome to the Internet (2017), cowritten with Julien Mailland, explored the three-decade history of Minitel, a system of connected terminals given for free to telephone subscribers by France Télécom in order to help spur a national “telematics” revolution. Minitel, which began in 1980 and was eventually superseded by the Internet as we know it, is often portrayed as a dead end in the history of communications, a cautionary tale of what could happen if we relied on a telephone company to lead computing innovation. Minitel’s clunky, beige plastic terminals quickly looked old-fashioned, and the system was incompatible with the broader changes taking place on the Internet, which ultimately left the national network behind. Mailland and Driscoll made a convincing case that Minitel is a network worth remembering and celebrating, not least because it created a business model—independent commercial services generating revenue collected from and shared with the phone company—that avoided the excesses of the corporate collection and sale of personal data, which Shoshana Zuboff warned of in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019). Minitel also maintained “generativity,” the ability to support novel uses and applications that Jonathan Zittrain celebrated in The Future of the Internet—And How to Stop It (2008).

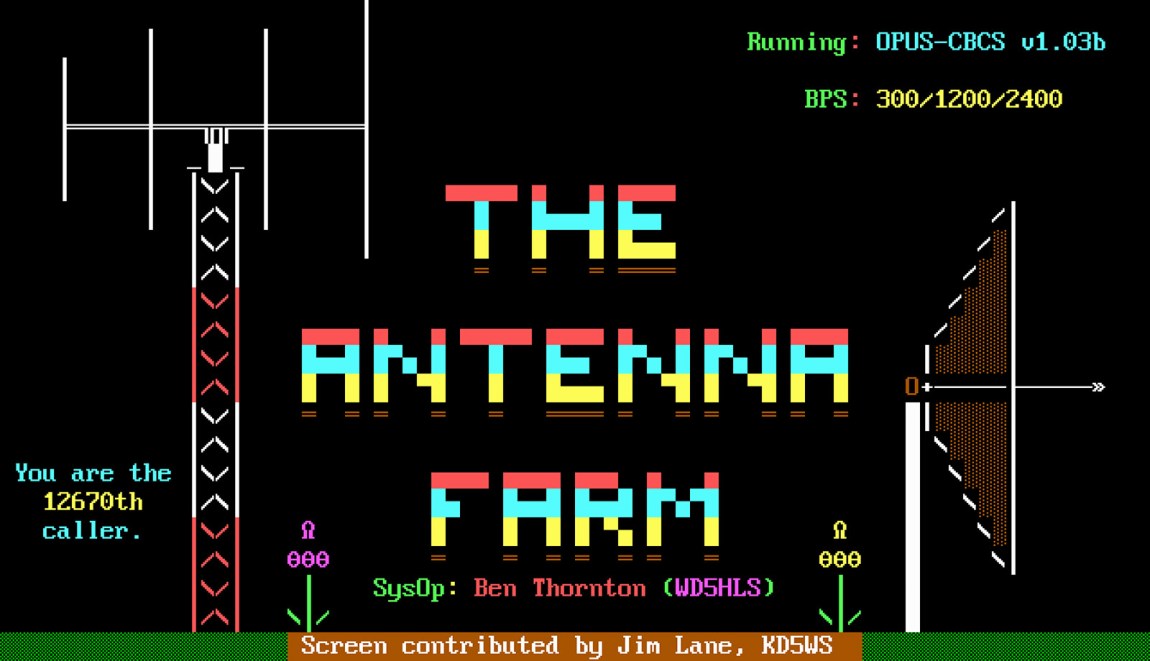

Driscoll’s project in The Modem World has an economic purpose as well: to praise the blend of small-scale capitalism and volunteerism that animated the world of bulletin-board systems (BBSes), operated by hobbyists and entrepreneurs to host conversations and the exchange of files between personal computer users in the same geographic area. These systems came into being in 1978 and disappeared quickly after the advent of the World Wide Web, but Driscoll argues that they had a powerful influence on computing culture during those twenty or so years, when they opened networked computing to people outside of university computer science departments.

Some of Driscoll’s best arguments come early in his book, tracing the spirit of BBSes back to amateur radio. Citizens Band (CB) radio, in particular, introduced a culture of talking with strangers that was depicted in movies like Convoy and Smokey and the Bandit. This culture helped energize the chat rooms of BBSes and later Internet service providers (ISPs) like America Online and CompuServe, which offered their own “walled garden” sites and services separate from the wider Internet, promising a safer and friendlier introduction to life online. The world of ham radio, with its need for operators to prove their fluency in Morse code, has a nerdier history, and Driscoll finds the roots of the personal computer hobby in the esoteric world of radio repeaters, who rebroadcasted one another’s signals in order to reach larger audiences than they could on their own.

Advertisement

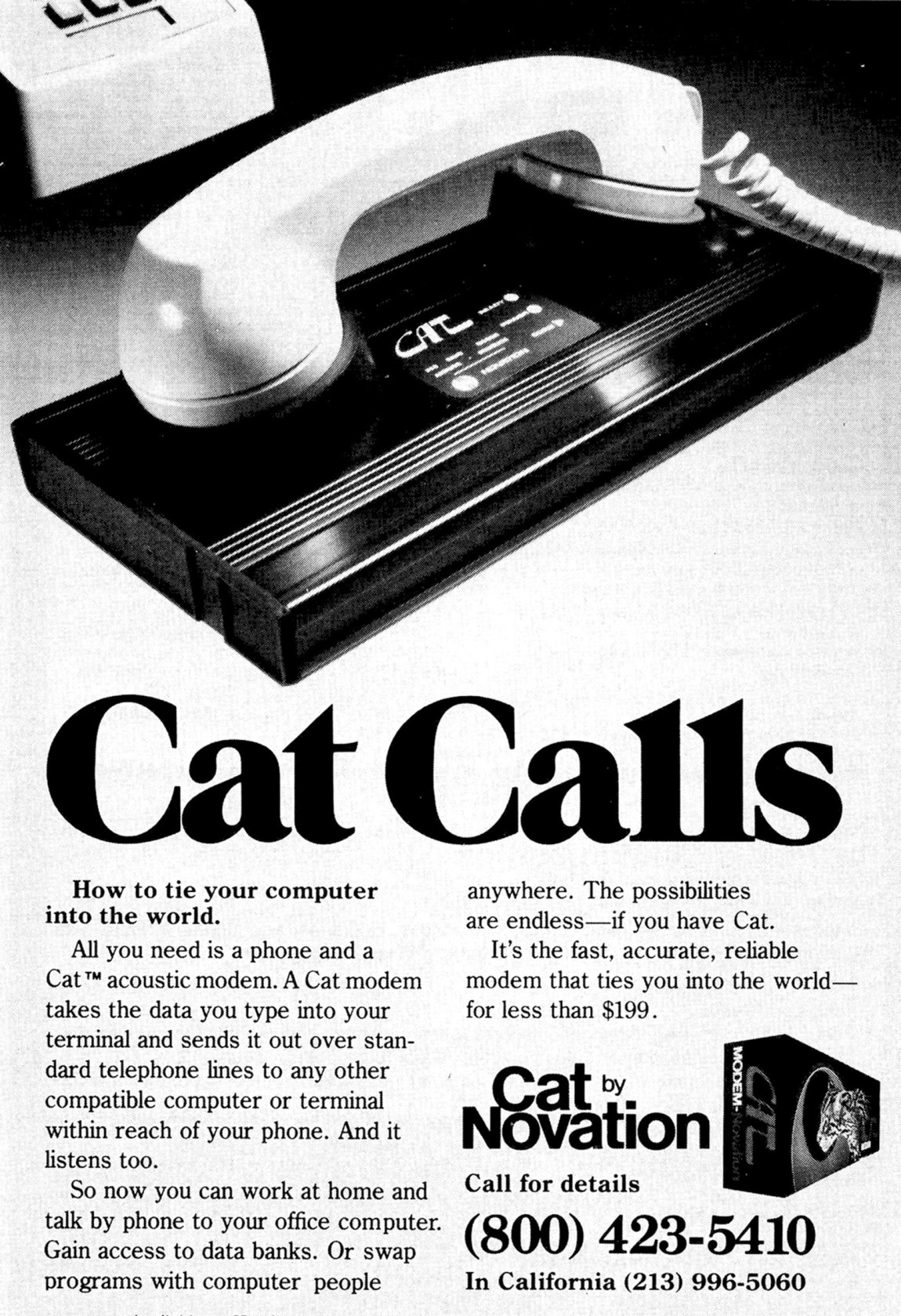

The legendary Chicago-based Computerized Bulletin Board System, created by the hardware hacker Randy Suess and the programmer Ward Christensen in 1978 during a snowy winter, shows the sheer imagination and audacity necessary to establish a novel form of digital interaction. Personal computers were extremely uncommon in the late 1970s, and modems—specialized pieces of hardware that translate data into audible tones for transmission over phone lines—even more so. That the members of the Chicago Area Computer Hobbyist Exchange, to which Suess and Christensen belonged, would want a virtual space to converse between in-person meetings wasn’t obvious. More creative—and transgressive—was the idea that Ma Bell’s sacrosanct telephone lines could be commandeered by ordinary citizens and used to facilitate often playful text-based conversations among geeks.

Other developments are more challenging for Driscoll to make lively. FidoNet was an ambitious effort to transmit messages between BBSes using a method called “store and forward”: one system would wait until another one closer to the recipient synchronized files and passed the message along to it. Driscoll is fascinated by the ways in which hyperlocal systems, accustomed to serving users who shared a telephone area code, attempted to become a global network. Readers, however, may not share his passion for the minutiae of global addressing schemes.

Still, Driscoll’s overall argument—that BBS culture helped shape contemporary Internet culture—is a persuasive one. The Modem World dedicates significant attention to text files, with which often pseudonymous users developed jokes, ideas, and short essays designed to circulate online. (Curious readers can find a large cache of these files, maintained as part of the Internet Archive, at textfiles.com.) Most histories of the social Web look backward from contemporary platforms like Reddit and 4chan to Usenet, the distributed discussion system that operated on university networks in the 1980s and 1990s. Driscoll points to groups like Cult of the Dead Cow, a loose organization of BBS operators and users whose activism can be credited with shaping the mythos of the rebellious, antisocial, political computer hacker that dominated media depictions until it was displaced by the hacker entrepreneur backed by venture capital.

Driscoll’s work is also a welcome corrective to narratives about the WELL, a San Francisco Bay Area BBS lauded by Howard Rheingold in his influential book The Virtual Community (1993). Because the WELL has been so thoroughly discussed in histories of social computing as an exemplary BBS, Driscoll takes pains to explain how unusual it was. Unlike other BBSes, which were run as hobbies by their owners, the WELL was comparatively well capitalized, ran on much more powerful computer hardware, and had a significant price tag for its users—$10 a month plus $2.50 an hour.

Rheingold praised the WELL for having “the atmosphere of a Paris salon”—created in part by giving complimentary accounts to prominent tech journalists. Following earlier historical research by the Stanford historian Fred Turner, Driscoll examines the network’s dependence on a dedicated audience of Grateful Dead fans who used the system to trade recordings and notes from recent shows. While Rheingold and others who have extolled the WELL have presented it as an example of how online spaces could host “high-minded discourse” and still be fiscally sustainable, it’s likely that these spaces were subsidized by less heady uses of the technology.

BBSes like GLIB (the D.C.-area Gay and Lesbian Information Bureau) illustrate Driscoll’s argument that many of them served as a means for connecting users with subcultural communities in their regions. In Life on the Screen (1995), the social scientist Sherry Turkle argued that the anonymity of cyberspace allowed individuals to explore their sexuality and other aspects of their personas free of consequence, due to the extreme malleability of the digital self. Turkle suggested that one’s digital self could be entirely separate from the rest of one’s life, but Driscoll sees BBSes as an online introduction to a “real world” group of fellow travelers and potential romantic partners. This gave rise to activist efforts: in the late 1980s and early 1990s, BBSes like New York City’s CAM (Computerized AIDS Ministries Network) provided critical connections for people living with AIDS and their caretakers, helping them to support one another in their immediate neighborhoods and around the world.

There are two topics that Driscoll seems reluctant to engage with in an otherwise comprehensive history of the BBS era. The first is the popularity of BBSes as a place for illicitly sharing copyrighted software, my personal introduction to the “modem world.” Driscoll writes that, because of the technological affordances of modems—limits on the amount of data they could transfer per second—early BBSes were more about conversations and text files than sharing programs, if only because that’s all the bandwidth would support. He also makes a strong argument for the importance of shareware—software made freely available but supported by donations that entitled users to technical assistance and documentation—as an economic model made possible by the distribution of software on bulletin boards. Shareware is a worthy topic for exploration, but free access to copyrighted material was a major motivation for many BBS users, as reflected on the cover of a 1993 issue of Boardwatch Magazine, which Driscoll includes as an illustration, showing an FBI raid on a system believed to be illegally distributing software.

Advertisement

The other lacuna is Driscoll’s very brief engagement with the large commercial dial-up ISPs, including CompuServe, AOL, and others. These platforms are now the objects of nostalgia about early online experiences, as on Hank and John Green’s podcasts and particularly in John’s book The Anthropocene Reviewed (2021). Driscoll shares a story of a student who, enthralled with tales of the early dial-up Internet, bemoaned the death of the alternative and queer-friendly world of AOL, misunderstanding it as a service primarily for gay and lesbian people to connect digitally, rather than the often bland attempt to bring sanitized online spaces into American households that it was.

Yet while the centralized, corporate-controlled nature of these services is far from the hyperlocal, barely capitalized model that Driscoll is most interested in, they were the introduction to the Internet for millions of early users, and their chat rooms and forums were visited by far more people than BBSes. The transition from BBSes to ISPs and the clash between local providers and the nationwide dial-up services may be the topic for another writer and another book.

Like many scholars of the early Internet, Driscoll casts its history as one of decline, from its early days of openness and inclusiveness to its current hostility and homogeneity. Nevertheless, he acknowledges this historical bias and its role in his larger project—his history of BBSes is not meant as a definitive account of this era but as an argument in favor of acknowledging ideologies and practices that have been forgotten in other histories of our shared digital life.

Ultimately, Driscoll is interested in imagining alternatives to the contemporary Internet. The structure of the current social Web, in which enormous companies manage incompatible, parallel services—Facebook, Twitter, etc.—reminds Driscoll of the bad old days when large ISPs drove many independent BBSes out of business. The ISP era, in turn, was disrupted by the rise of the World Wide Web in the mid-to-late 1990s, when proprietary, closed networks were outcompeted by the new combination of the academic Internet and the gentle learning curve of HTML, the programming language of the newly launched websites.

One camp that seeks alternatives to contemporary social media has termed itself Web3. The name implies the next revolution beyond Web 2.0, a marketing term popularized by Tim O’Reilly to refer to the user-generated, participatory Internet that arose at the beginning of the 2000s and eventually became the Internet of powerful platforms like Facebook. Web3 partisans promise a return to the decentralized structure of the original Web but with all the convenience of the participatory Web and the added benefit of imaginary Internet money that only ever increases in value. Using blockchains—a form of decentralized ledger popularized as a mechanism to prevent double-spending of digital currencies like Bitcoin—some Web3 networks reward users for their participation with coins that also function as votes on issues of community concern. At best, Web3 is an ambitious attempt to call attention to questions of governance of online spaces and speech.

Efforts to govern online spaces through the resulting tokenized democracy may seem a more appealing vision of community governance than Facebook’s, in which a company in California makes a set of opaque rules that are enforced by poorly paid moderators in developing nations. On the other hand, blockchains are computationally expensive, spending unseemly amounts of electricity to ensure that no fraud is committed, which makes most current implementations an environmental disaster. Furthermore, it’s not clear that rewarding participants for contributing to social networks makes any aspect of online community participation healthier or more inclusive. Indeed, the fact that coins serve both as speculative currencies and proxies for voting seems a recipe for a plutocracy rather than a traditional democracy.

It’s here that The Modem World is most relevant to contemporary debates. Seeing Web3 as an alternative to the current Web is the logical extension of the standard history that emphasizes the decentralization of the academic Internet and financial speculation on digital services. While Web3 promises that those most active in building future communities will be the ones to own and control them, it has become the latest frontier for venture capital investment. And just as venture capitalists profited from their investments by selling small start-ups to hungry Internet behemoths, Web3 already finds itself centralizing, with a tiny minority of coin holders controlling most of the wealth, and a few companies and projects acting as effective chokepoints for the rest.

Driscoll believes we can envision a different future by looking back to earlier versions of the Internet. BBSes experimented with different financial models, such as subscriptions, fee for service, and soliciting donations. Successful BBSes focused on the community, not profit, engaging in the person-to-person work required to ensure users’ needs were met and their feelings taken into consideration. This work still happens in online communities today, Driscoll reminds us, but the moderators who maintain Reddit’s subsections or manage groups on Facebook have no financial stake in the endeavor or any control over the tools they use. Were we to learn the lessons of BBSes, we might demand ownership of and control over our online communities, rather than allowing them to be taken over by companies that see users as products to be marketed to their real customers, the advertisers.

For Driscoll, BBS operators had a reciprocal relationship with their users. If the BBS did not meet their needs or take their concerns seriously, users would abandon the community and move to another one. BBS users who believed the system’s operators listened to them and responded might be willing to pay to support a hardware upgrade or other improvements to the service. Such communities were not democracies, but they were often benevolent autocracies.

Soon, four of the most popular Internet community platforms—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Twitter—will be controlled by two billionaires. Mark Zuckerberg has an unusual degree of power over the companies owned by Facebook/Meta, because of his status as CEO and as the holder of “founders shares,” which give him an effective veto over the rest of his board of directors. Elon Musk has made a successful bid to purchase Twitter and take it off the stock market, removing what little transparency and safeguards come from its being a public company. Neither man—two of the richest in the world—has reason or inclination to listen too closely to the concerns of his community members.

At such a moment, it’s worth considering other platforms that would be more democratic and inclusive, where users are asked to help govern and moderate. Mastodon, an open-source alternative to Twitter, allows individuals to operate servers in much the same way BBS operators did, establishing a set of rules and inviting people to participate in the conversation or find another server that better meets their needs. Mastodon thus far has mostly been embraced by groups that have been chased off mainstream platforms. For some years, one of the most successful Mastodon communities—switter.at—was run by and for sex workers in Australia.

There’s no question that hate groups will join such “distributed social networks.” They already have—Gab is, in a sense, a smaller social network for people whose opinions would get them banned from Twitter, and even more extreme groups, like Stormfront, exist in other corners of the Internet. The goal with distributed social networks is not to ban offensive speech, which would be constitutionally difficult to do, but to keep it from blending into the mainstream, so that people are not falling into “rabbit holes” during normal use of the platform. People would have to choose to engage with an extremist network, rather than have extremism creep up on them.

With decentralized social networks, users, not the companies running the platforms, decide what sorts of speech are allowed. Membership in one might involve regular shifts as a content moderator, much like jury service. Participants who are especially passionate about online governance could campaign to serve in legislatures that would debate terms of service and the enforcement of them. Experiments in my lab at UMass Amherst, along with projects at Cornell, the University of Washington, and CU Boulder, seek to test whether such communities could sustain self-government, and whether participation in this form of online governance could have positive impacts on broader, “real world” civic participation.

It may be hard to imagine a future in which Facebook is undone by a return to independent community management by hobbyists. But our ability to imagine alternatives is directly related to the histories we tell. If the history of social media is that of an academic network given vitality and life by the brilliance of Silicon Valley venture capitalists, we can never conceive of a people’s network. If our history runs instead through the bulletin-board systems, we cannot help but envision futures that include communities created for community’s sake.