“Whether he poses or is real,” Thom Gunn wrote in one of the first poems inspired by Elvis Presley, “no cat/Bothers to say.” To many British men who came of age during the austere and repressive 1950s, from the formidably erudite and Cambridge-educated Gunn to streetwise Scousers such as John Lennon and Paul McCartney, Presley embodied a fantasy of American maleness at its most charged and appealing. In “Elvis Presley” (1955), written even before the King’s first album was released, Gunn skillfully incorporates his new hero into the galère of existential toughs whose ability to “pose” he would celebrate and imitate throughout his career. By September of the following year, he is considering changing his contributor’s note to read, “Is 27, has been twice arrested, likes motorcycles and Elvis Presley,” before claiming to his correspondent, the gay but much less swinging John Lehmann, editor of London Magazine, that Presley “used to be a hustler in New Orleans.” This is followed by a covert boast: “I have this from his fellow hustlers.” Gunn writes not as one “cat” to another, but as an initiate delivering bulletins from the frontier of American promiscuity to a fuddy-duddy too timid to leave stuffy old Blighty.

“The pose held is a stance,” Gunn’s poem concludes, “Which, generation of the very chance/It wars on, may be posture for combat.” As is so often the case with Gunn’s early poems, this takes some parsing. Presley’s “gangling finery/And crawling sideburns,” along with the guitar that he is described as “wielding,” align him with the combative yet self-conscious personae populating Gunn’s first collection, Fighting Terms (1954). The “pose,” whether adopted by Presley or the speaker of poems such as “Carnal Knowledge” (which opens, “Even in bed I pose”), enacts both defeat and victory: if from one perspective it registers as a futile gesture in the face of impossible odds controlled by the vagaries of chance, from another it dramatizes admirable defiance and uplifting chutzpah, turning the spirit of “revolt into a style.” While the knotty, rebarbative aspects of Gunn’s early manner can make this poetic tribute verge on the condescending, or at least guilty of overthinking the primal energies on display in any Presley performance, its heart is undoubtedly in the right place: as he was for the early Beatles, Presley is at once excitingly distinctive and yet available for emulation—“Our idiosyncrasy,” as the poem compactly phrases it, “and our likeness.”

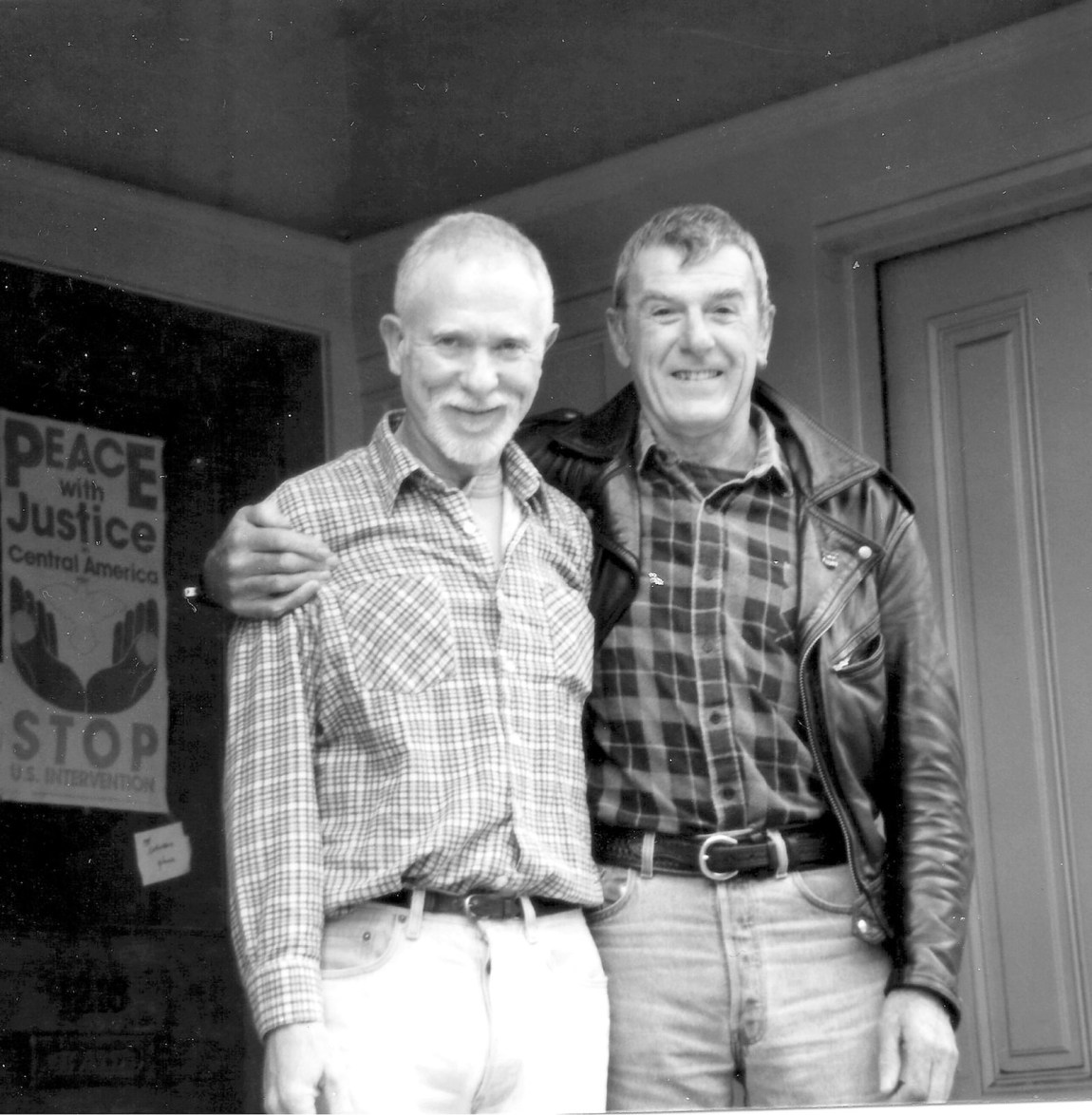

Gunn’s concept of the pose is strikingly in evidence in the photo chosen for the UK cover of this edition of his letters. Robert Frank was Gunn’s favorite photographer, and in a letter from the mid-1990s he recalls buying Frank’s book The Americans a couple of years after it came out and admiring the way Frank’s pictures “caught a rough-housing, sweet-natured, sexy side of America.” The leather-jacketed and biker-booted Gunn captured posing, one leg provocatively akimbo, against a lamppost on some Main Street in 1958 (the year The Americans was published), evokes all the adjectives that Gunn applied to Frank’s vision of America.

But as is so often the case with Gunn, it is the element of disjunction that we are really being asked to admire: his second book, The Sense of Movement (1957), had just been published to a chorus of admiring reviews; he had sat at the feet of the morally exacting literary critic F.R. Leavis at Cambridge, had embarked on a Ph.D. on Wallace Stevens under the equally high-minded Yvor Winters at Stanford, had just accepted from Josephine Miles a post teaching at Berkeley (on whose staff he remained for most of the next forty-two years); along with Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin, he was the new next big thing in British poetry. Nevertheless, the unillusioned, hooded eyes seem to declare that it was equally important to be able to pass as just the sort of hustler with whom Presley had reputedly hung out in New Orleans, or as one of Marlon Brando’s posse of ne’er-do-well bikers in The Wild One.

Gunn’s pervasive fascination with disjunction undoubtedly had its origins in his formative years. Born in Gravesend in 1929, he grew up mainly in London, where his father was an editor employed by newspapers such as the Evening Standard and the Daily Express. His parents’ rocky relationship finally ended in divorce in 1939, and the following year his mother, Charlotte, married a much-detested stepfather, Joe Hyde, also a newspaperman. A couple of days after this second marriage decisively foundered, in late December 1944, Charlotte committed suicide by inhaling gas from a now-obsolete implement called a gas-poker, used to help to light coal fires. It was Gunn and his brother Ander who found her body, he recalled in the moving late poem “The Gas-poker” (composed in 1991), which is characteristically written in the third person, as if he were a detached observer coolly watching his adolescent self and younger sibling in the act of making their dreadful discovery:

Advertisement

Forty-eight years ago

—Can it be forty-eight

Since then?—they forced the door

Which she had barricaded

With a full bureau’s weight

Lest anyone find, as they did,

What she had blocked it for.

The intricately patterned rhymes and wondering tone of “The Gas-poker” elegantly transform a scene whose traumatizing details Gunn had set down in his journal on the day of her death:

There was a smell, not a very

horriblegreat one, of gas. It haunted us for the whole day afterwards. I turned the gas off and Ander took the gas poker out of her hands.

We didn’t undo the blackout for we could see her

perfectlywell by the light from the French windows, open behind us.

We uncovered her face. How horrible it was! Ander said afterwards to me that the eyes were open, but I thought they were closed; she was white almost, like the rest of her body that we could see. “Cover it up. I don’t want to see it. It’s so horrible,” Ander cried. Her hed [sic] was back, and the mouth was open,—not expressing anything, horror, sadness, happiness,—just open.1

Poor Charlotte’s open mouth returns in the final stanza of “The Gas-poker,” which again exemplifies how an imagined pose or fantasy, in this instance that of a flutist playing—or rather being played by—a “backwards flute,” can bridge the gap between seemingly incompatible worlds. In Gunn’s elaborate conceit the deadly gas is imagined as music, and Charlotte’s suicide is recreated as an inverted artistic performance; rather than her breathing into the flute, it breathes into her, filling her with music’s antithesis, silence:

One image from the flow

Sticks in the stubborn mind:

A sort of backwards flute.

The poker that she held up

Breathed from the holes aligned

Into her mouth till, filled up

By its music, she was mute.

Gunn, as he frequently insists in his letters, abhorred the expressionist techniques deployed in so-called confessional poetry. “The Gas-poker” records a “horror” as extreme as any to be found in Sylvia Plath’s or Robert Lowell’s poetic accounts of their lives, but it does so in a manner that is cerebral and distancing. Indeed, in another late poem about Charlotte, “My Mother’s Pride,” Gunn explicitly figures her as a reckless confessional type avant la lettre. “She dramatized herself,” this poem opens, “Without thought of the dangers,” which was exactly the sort of charge often leveled by critics at Plath and her followers. Gunn once remarked in an interview, when quizzed about the emotional reticence of his poems, “I don’t like dramatizing myself. I don’t want to be Sylvia Plath.” And while the final line of “My Mother’s Pride”—“I am made by her,” Gunn reflects of his mother, “and undone”—may at first look like a Plathian cri de coeur, it is in fact an allusion to the plangent but witty response of the Renaissance poet John Donne to the professional ostracism that he suffered after his clandestine marriage to his boss’s daughter. “John Donne, Anne Donne, undone,” wrote the disgraced courtier in a letter to his wife shortly after they wed.

Donne was prominent on the English literature curriculum at Cambridge in the 1950s and proved a crucial influence on the young Gunn’s quest for a poetry that was radically self-aware (“You know I know you know I know you know” is the refrain of “Carnal Knowledge”), metrically taut, and strenuously argued. “Donne gave me the licence both to be obscure,” he recalled in an autobiographical essay from 1977, “and to find material in the contradictions of one’s own emotions.” Donne, along with Fulke Greville, Walter Raleigh, Thomas Campion, John Dowland, Ben Jonson, and George Herbert, remained Gunn’s gold standard for poetry throughout his career, and by imitating and updating their lyrics he hoped to achieve in his own work just the sort of “impersonality” (his highest term of critical approbation) so valued by T.S. Eliot, as well as by Gunn’s own mentors, Leavis and Winters.

With hindsight, however, the quasi-metaphysical obscurities of Fighting Terms, published a year after he graduated college, register mainly as a convoluted code for the love that dared not speak its name in that era and was punishable with fines (as the actor John Gielgud discovered in 1953), disgrace, or prison. In his second year at Cambridge, Gunn fell in love with an American, Mike Kitay, who became his lifelong partner, or rather companion, for, rather to Kitay’s chagrin, the disjunctive Gunn was not cut out for a monogamous relationship. One learns of many thousands of sexual encounters from both his poems and the missives included in this volume (which, long as it is, collects less than one tenth of Gunn’s surviving correspondence).

Advertisement

Even letters fired off in his late sixties and early seventies recount prolonged bouts of vigorous sex with younger men picked up on the streets or in leather bars, as well as copious consumption of speed and other pleasure-enhancing drugs. “My wants are very few,” he muses only semi-ironically in a letter from 2000, the year after he retired from Berkeley, “drink, drugs, a mad biker with an imaginative cock and an infinitely hungry hole, a loving family and a fairly warm climate. Very Horatian!” In his era-spanning fashion, Gunn clearly delighted in figuring the queer ménage over which he presided at 1216 Cole Street, near the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, as a late-twentieth-century California equivalent of the Latin poet Horace’s Sabine farm.

“In a capitalist country,” Frank O’Hara once remarked, “fun is everything.” The effortlessly spontaneous O’Hara and the infinitely calculating Gunn would not have agreed on much, but from their antithetical aesthetic positions, both were committed to a poetry of hedonism.2 Further, the best poetry of both derives from their involvement in particular coteries and from their ability to celebrate friendship—or to lament the deaths of friends—in fresh and original ways. “You just go on your nerve” was O’Hara’s mantra, while nearly every Gunn poem advertises the craft and labor that has gone into its making.

These letters vastly increase our understanding of his painstaking compositional processes, for many of them were written to elicit feedback on work in progress from a trusted band of first readers. Like O’Hara, Gunn disdained the literary establishment, but he cared deeply how friends, such as the literary scholars Tony Tanner and Douglas Chambers or his Cambridge friend the mercurial and fascinating Tony White, responded to his work. Reading his contributions to these epistolary exchanges, one is struck by his startling lack of hubris or defensiveness—his openness, even late in his career, to advice and criticism.

Gunn’s commitment to a rigorous use of form and meter and an obtrusively literary diction slowly dissolved as he acclimated to America’s permissive poetic zeitgeist. Winters introduced him to the poetry of Stevens and William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore, and by the mid-1960s he was happily trying his hand at syllabics and free verse, while at the same time developing less stilted, more colloquial registers in his formally prosodic work. He was also gradually converted to the merits of any number of poets whose wild and woolly ways were anathema to the sensible ideals of writers such as Larkin and Kingsley Amis, who were associated with the Movement, into whose ranks Gunn had initially—and rather against his will—been co-opted. (Reacting against the vatic exuberance of Dylan Thomas and his followers, the Movement poets of the mid-1950s prided themselves on understatement, irony, controlled use of form, and an interest in the everyday.) Robert Duncan (who became a close friend), Gary Snyder, Robert Creeley, Allen Ginsberg, and Lorine Niedecker would all in due course be championed in essays intended to open the eyes of insular British readers to the intrepidly experimental glories of twentieth-century American verse.

This embrace of expanded poetic possibility matched Gunn’s determination to open the doors of perception whenever opportunity presented: he tried LSD for the first time in June 1966, and despite initially suffering from “incipient paranoias” soon developed into a fervent advocate of the druggy utopianism symbolized by the Summer of Love in 1967. A number of poems in his collection Moly (1971) are attempts to create poetic equivalents of the trip, as well as to do justice to the ideals of the counterculture as played out in the hippie heaven of San Francisco.

“Moly” was the name of the flower that Hermes gave Odysseus in order to protect him from the spells of the witch Circe, who had turned his companions into beasts. It serves as a symbol for Gunn of the metamorphic powers of all the substances peddled by the dealer in “Street Song”—“Keys lids [different measures of marijuana] acid and speed.” As he explained in a letter to Tanner, whom he had recently initiated into the joys of acid, the book presents moly as “the antidote to piggishness in man.” Poems such as “At the Centre” and “The Fair in the Woods” explicitly draw attention to their sources in memorable acid trips. The latter reenacts the particularly Gunnian experience of dropping a tab of LSD and then visiting a Renaissance fair, held in Marin County, at which people donned Elizabethan dress and acted like extras in a crowd scene in a Shakespeare play: woodsmen wearing buckskins and blowing horns jostle with Blakean “children of light” clustered in trees, and the day climaxes in “one long dazzling burst” of hallucinatory unpiggishness.

For Gunn, one should immediately add, unpiggishness never involved sublimating the pleasures of the flesh, and at times these letters had me marveling at the sheer stamina involved in his quest to explore the different “passages of joy,” to use the title of his 1982 collection—itself borrowed from Samuel Johnson’s “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” A letter from 1969 to Tanner recounts a six-hour LSD trip in which life became “a complete flowing” and Gunn found himself on a San Francisco rooftop besting the Almighty Himself in an argument: “I can tell you, I put some pretty challenging propositions to God, and he gave me no answer.” And yet, as if that weren’t enough for one day, by evening he was to be found in the bar the Stud, where he notes that his post-trip “air of self-sufficiency” and still-enlarged pupils made him especially appealing.

“I am the W of Babylon herself,” he confessed—or should that be boasted?—to Douglas Chambers after recounting in a letter from 1996 his latest adventures, first with a bookstore clerk who “loves having sex in leather” and then with an “utterly handsome” if rather dirty drifter; both were in their mid-twenties, while the still-ardent and fully functioning Gunn was approaching sixty-seven. Three years later he records “a 36 hour sexual epiphany” with John Ambrioso, who in this book’s glossary of names is described as Gunn’s “regular trick” during his declining years and as “part of the methamphetamine scene that TG became involved in after his retirement from teaching.” His involvement in this scene clearly hastened his death at the age of seventy-four: the coroner’s report recorded a mix of meth, heroin, and alcohol as the cause of his fatal heart failure in April 2004.

Gunn is undoubtedly at his strongest as a poetic portraitist. His work in this genre ranges from sketches of characters fleetingly encountered in the streets and bars of San Francisco and New York, somewhat in the mode of Baudelaire’s Tableaux parisiens, to character studies of gay notables like those in “Transients and Residents” (1980), to moving elegies for friends, many of whom died of AIDS. Preeminent in this gallery of the departed is “Talbot Road” (1979–1980), a five-part tribute to Tony White, to whom many letters included in the first half of this volume are addressed. Gunn met White at a party in Cambridge in 1952, and they instantly bonded over the writings of Stendhal, another of Gunn’s early enthusiasms. In his memoir “Cambridge in the Fifties” (1977), the year after White’s untimely death at the age of forty-five from a blood clot that developed after he broke a leg in a soccer match, Gunn depicts them as enjoying what the Germans would call a Blutsbrüderschaft:

We formed projects together, we studied books together, we even found, to our amusement, that we both affected the same check shirts, which we had bought on Charing Cross Road, making us look, we hoped, more like Canadian loggers than Cambridge undergraduates.

White (who was straight) was prominent in Cambridge theatrical circles, and after college was employed for a couple of seasons by the Old Vic, playing Cassio to Richard Burton’s Othello in 1956, along with a series of lesser Shakespearean roles.3 Mysteriously, however, that spring he decided to abandon the theater, taking instead a job as a lamplighter in the East End. To the industrious and resolutely persevering Gunn, who would toil, over individual poems for years, if necessary, the reason given by White—that there were too many “creeps” in the acting world—seemed specious. “You are far too good an actor to be spared,” he protested, before pointing out that “there are going to be creeps around in any job.” Gunn was all for “panache”—for “l’imprévu, singularité,” to quote from a card that White sent him in 1954 and that codified their existential belief system (it is signed “from one Étranger to another”)—but found White’s lack of discipline or commitment to a vocation puzzling.

Despite his early promise and wide-ranging intelligence, White spent the next two decades subsisting on temporary jobs, working as a handyman and painter, tinkering with a TV script and an unfinished novel, and researching and publishing a guide to the pubs of London. In the measured and moving “Talbot Road,” Gunn broods on the magnetic White’s charisma and elusiveness, on his Hamlet-like uncertainties, on their shared credo of the pose:

Glamorous and difficult friend,

helper and ally. As students

enwrapt by our own romanticism,

innocent poet and actor we had posed

we had played out parts to each other

I have sometimes thought

like studs in a whorehouse.

—But he had to deal

with the best looks of his year.

If “the rich are different from us,”

so are the handsome. What

did he really want? Ah that question…

The poem is an extended reminiscence of the nine months that Gunn spent living on Talbot Road in Notting Hill Gate in 1964–1965, a sabbatical funded by an award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters. White lived nearby, and the poem brilliantly recreates the ebbs and flows of their friendship (“I was too angry to piss,” Gunn explodes in a rare tiff between the two in a London pub), as well as the exhilaration of the city’s transformation from postwar austerity to swinging Sixties permissiveness. Hampstead Heath, near Gunn’s childhood home in Frognal, is the site of games very different from those that he had played as a youngster:

I knew every sudden path from childhood,

the crooks of every climbable tree.

And now I engaged these at night,

and where I had played hide and seek

with neighbour children, played as an adult

with troops of men whose rounds intersected

at the Orgy Tree or in the wood

of birch trunks gleaming like mute watchers…

Sex, or so the poem suggests, was as important to White’s quest for happiness as it was to Gunn’s. We learn of multiple simultaneous romances undertaken by the “Fantastical duke of dark corners,” to use the epithet Gunn here bestows on him, borrowed from Shakespeare’s most graphic exploration of illicit erotic behavior, Measure for Measure. Although composed fifteen years after the time it commemorates, “Talbot Road” brilliantly recreates London on the cusp of liberation, in which the formerly marginalized buoyantly assume center stage. The idyllic year climaxes in a midsummer going-away party on a canal boat arranged for the poet by his friend, and as they slip “through the watery network of London,” it is as if both the poet’s and the city’s hidden privacies emerge effortlessly into the open. “Now here we were, buoyant,” he reflects,

gazing in mid-mouthful

at the backs of buildings, at smoke-black walls

coral in the light of the long evening,

at what we had suspected all along

when we crossed the bridges we now passed under,

gliding through the open secret.

In its understated way, this can be read as the apogee of the bildungsroman traced by Gunn’s poetic oeuvre, as the moment the occluded requires no agency to declare itself, and the closet is revealed without shame or obfuscation.

Within a few years of the publication of “Talbot Road” in The Passages of Joy, however, the utopian future so boldly figured by Gunn in his midcareer volumes was being undermined by the spread of AIDS. “San Francisco is not the happiest of places now,” he grimly reports in a letter from December 1984 to his aunts back in Snodland, Kent. “I know a lot of people who have died of AIDS. As everybody says, it is like the Plague—you don’t know who is going to get it next but it is going to get a lot more people before it is finished.”

Gunn’s elegies for friends such as Allan Noseworthy, Larry Hoyt, Jim Lay, Norm Rathweg, and Charlie Hinkle are included in section 4 of his penultimate and most justly celebrated volume, The Man with Night Sweats (1992). In these postmortem portraits, Gunn achieves a highly effective balance between heartbreaking details and the soothing consolations of form and rhyme. The conceits deployed, however elaborate, communicate the most primal of emotions—loss, pain, stoical endurance, fits of despair—as well as the survivor’s inability to make sense of the wanton destruction of so much promise. The poems set in hospitals are particularly wrenching, for in them Gunn itemizes the doomed attempts of medical interventions and instruments to halt the inexorable failure of the body:

Meanwhile

Your lungs collapsed, and the machine, unstrained,

Did all your breathing now. Nothing remained

But death by drowning on an inland sea

Of your own fluids, which it seemed could be

Kindly forestalled by drugs. Both could and would:

Nothing was said, everything understood,

At least by us.

As in Whitman’s poetic accounts of the visits that he paid to wounded soldiers in Washington hospitals during the Civil War, the process of witnessing serves to frame the suffering endured, and indeed registers, like the poem itself, as a profoundly needed act of caring for the body in extremis. The euphemism “kindly forestalled” is wryly, even tenderly proffered, while the artful figuration of fatal pneumonia as “death by drowning on an inland sea” illustrates as delicately as the image of the “backwards flute” in “The Gas-poker” Gunn’s ability to fuse ingenuity and compassion in a manner more often encountered in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century poetry than in the work of his contemporaries.

Gunn was fully aware that the crisis had brought out the best in him as a poet: in a sobering note made in his diary at the end of the 1980s, he summed up the ten most important things that had happened to him that “awful decade.” Number 1 is “AIDS invented itself,” and most of the rest are the deaths of friends, but number 10 modestly offers something of a counterbalance: “I wrote a lot of good poetry, which is the only other good thing that happened, of importance.”

-

1

This extract from Gunn’s journal is included in the notes to the poem in Clive Wilmer’s excellent edition of Gunn’s Selected Poems (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017). ↩

-

2

Gunn refers briefly to their differences in a letter from 1994, in which he enthusiastically endorses Brad Gooch’s biography of O’Hara, City Poet (Knopf, 1993): “The fact that his [O’Hara’s] way of working is about as far from mine as I can imagine only ADDS to the interest. It is a very enjoyable book and I recommend it!!!!” ↩

-

3

For a full exploration of Tony White’s life, see Sam Miller, Fathers (London: Jonathan Cape, 2017), in which Miller recounts his discovery at the age of sixteen that White, rather than the editor and literary critic Karl Miller (also a Cambridge friend of Gunn’s), was his biological father. ↩