This mesmerizing oddity opens with a prefatory couple of pages about something—some sort of memoir or testimony—that the narrator has just finished writing:

I was gradually forgetting my story. At first, I shrugged, telling myself that it would be no great loss, since nothing had happened to me, but soon I was shocked by that thought. After all, if I was a human being, my story was as important as that of King Lear or of Prince Hamlet that William Shakespeare had taken the trouble to relate in detail.

Before calmly delivering this striking and eccentric declaration, she mentions spending “a lot of time in one of the armchairs, rereading the books,” and paying particular attention to the books’ prefaces, which consist largely, to her bewilderment, of the authors’ rationales for having written the books—as if, she muses, passing along ideas and information called for explanation or apology. The reader might be somewhat unbalanced in turn by the narrator’s astonishment about prefaces, especially since she is here explicating the raison d’être of her own book.

There are other puzzling elements in this short space. For example, “in one of the armchairs”—that’s a conspicuously peculiar turn of phrase: In one of what armchairs? If the armchairs belong to the narrator, wouldn’t it be more natural for her to say “in one of my armchairs” or “in an armchair”? And what books? If she likes books so much, why doesn’t she go get some other books, books she hasn’t already read?

We have also learned that she is alone, that she is gravely ill, that she has just, for the first time in her life, experienced powerful feelings—grief over the death, at some unspecified earlier time, of her friend Anthea. But we must wait for these patches of information to cohere into a picture, because at this point we slide into what is presumably the narrator’s document, the story beginning decades before of the “nothing” that has happened to her.

She was by far the youngest, she tells us, in a group of thirty-nine other captives, all women—so young when they were imprisoned together that she does not know her own name. The others refer to her simply as “the child.” It seems that their captors took great trouble to be sure that the women were from different areas of the country and had no connections to one another. Trauma has shattered their recollections of the violence and upheaval that surrounded their capture, and increasingly, as featureless time wears on in the cage where they’re imprisoned, with no foreseeable alteration to the situation or release from it, futility converts memories of their stolen lives from solace into dead weight.

The periphery of the cage is patrolled by two shifts of three men, who crack their whips with great skill and precision at any glimpse of an infraction: each woman must be fully visible at all times. None of them is allowed to cry, to resist sleep or food, to touch, or to attempt suicide. The guards keep some distance between one another—perhaps to ensure that their own behavior conforms to regulations. They never actually strike any of the women with the whips, though some of the women bear scars of lashes and harbor faint impressions of pain that date from the time of their capture. To all of them the threat of the whip is potent.

The inmates have no way to tell time, or to judge how much time is passing. There’s no natural light in the cage; intervals of artificial light signify day. Provisions—meat and vegetables—are supplied on each of these putative days, and the cage is equipped with a stove and running water. The only way the food can be prepared is by boiling, and there is nothing with which to flavor it. Usually there’s a satisfactory amount, but sometimes the supply is not quite adequate—an imbalance clearly intended to demonstrate the arbitrary exercise of power rather than to starve anybody; these prisoners have been condemned to life.

“I was surly all the time, but I was unaware of it, because I didn’t know the words for describing moods,” the narrator writes. And her vague recall of her early years in the cage doesn’t merit the word “memory”; all she had was

the sense of existing in the same place, with the same people and doing the same things—in other words, eating, excreting and sleeping. For a very long time, the days went by, each one just like the day before, then I began to think, and everything changed…. My memory begins with my anger.

Who would not be angry under these conditions—who would not be surly! But it turns out that it’s not the endless monotony or debasing deprivation of privacy and freedom that drives the narrator into a fury, but her helpless ignorance. She is aware that the women have had all sorts of experiences she cannot have, that they know about things she is not able to grasp—that they know, for instance, what is meant by “a fine day.” She is aware that they have conversations that give them pleasure and even make them laugh—conversations from which she is excluded, about their previous lives, specifically about men. And she believes that the women are maliciously concealing something from her, a secret of great value.

Advertisement

Her revenge is to retreat into private thoughts, where she establishes her own secret. One of the guards—all rather elderly men by now—has been replaced by a young man, and she watches him fixedly, though he appears to take no notice of her. Gradually she discovers that she can tell herself stories about him—about him and herself—which produce in her a sensation she refers to as an “eruption,” a sensation that, naturally enough, she sets about trying to cultivate. By locating and harnessing her dormant capacities for observation and imagination, and directing their interplay to refine, amplify, extend, and revise what she discovers she can make with them, she learns to tell herself increasingly detailed, increasingly effective stories.

Anthea, the kindest among the women to the narrator, explains that the others were not maliciously concealing something from her; they only hoped to spare her the torment of longing for a world she’ll never experience. She herself trained as a nurse, but the others were factory workers and shop assistants and so on, and do not feel equipped to try to pass along any education to the narrator. And in any case, how would it be possible to teach her much of anything? The lack in the cage of even the simplest tools, like writing implements and any surfaces on which they could be used, is a tremendous obstacle to transmitting basic skills like reading, writing, and more than simple calculations.

Our own sense of time, age, and sequence is blurry as we read; here, near the beginning of the account, Anthea conjectures that the narrator, who has been growing and has entered puberty, is about fifteen. Alterations in the bodies and appearances of the rest of them, all adults, are nearly unnoticeable, and in the utter stasis of the cage, the narrator has embodied change and demonstrated time passing. But now, as her nascent desire loses energy, her body ceases to develop—she barely has breasts, and she doesn’t menstruate. Some of the others stopped menstruating long before, but that’s not, Anthea says, because they’re old:

“It isn’t the menopause that has withered us, it’s despair.”

“So men were very important?”

She nodded.

“Men mean you are alive…. What are we, without a future, without children? The last links in a broken chain.”

The narrator, too, is at an impasse. For want of fuel and air, her stories are stifled, and her interest in the guard lapses.

Sex and rage have taught her how to think, and although those impulses have now been starved—her emotional life is arid, and her body remains in some ways a child’s—nonetheless, her ability to think is ineradicable. And with this and Anthea’s help, she devises an ingenious, though extremely laborious, way of measuring time. This scientific advance confirms her suspicion that the duration of artificial days and nights in the cage is inconsistent. But momentous as it is, the discovery reveals nothing at all about the reasons for the inconsistency.

The state of affairs is as unyieldingly opaque to the book’s readers as to its characters. Why have these particular women been selected—or have all women everywhere suffered the same fate? Is it only women who are confined to cages? What was the great upheaval or catastrophe that changed all of life? Was there a war? Where are they? Are they even on the planet Earth? How much time has passed since they were initially imprisoned? Are their guards human or are they sophisticated robots, are they invested with great authority or are they acting under compulsion? To whom do they answer? Why was the older guard replaced by the young one—does it indicate some change of policy? Or is there no significance to it at all? Why was the child incarcerated with adults? Was it a means of sowing discord or creating confusion, or was it some sort of error or the random result of a sweep? The women have not been accused of anything, there have been no interrogations, they are not enslaved, so what role do they have, for whom, and in the service of what ideal or purpose? And is it possible that they have simply been forgotten?

Advertisement

I understood that I was living at the very heart of despair…and that all these women who lived without knowing the meaning of their existence were mad…. They’d lost their reason because nothing in their lives made sense any more.

And the narrator herself, who, having experienced “nothing,” has no means of imagining much beyond what can be observed in the cage, and therefore no means of feeling much beyond resentment, wonders from time to time whether she even qualifies as human.

The glow of dying light sweeps across the book. It would be a shame to reveal everything that’s to be encountered in the vividly barren landscape of its later pages, although it’s necessary to disclose that—owing to what seems to be a freak accident in the course of some sort of system failure—the women are released. But when this miracle occurs, only a few of their questions are answered—many more are actually compounded, and the women find themselves free in a world that’s hardly less austere or more comprehensible than was the prison where they’ve spent so many years.

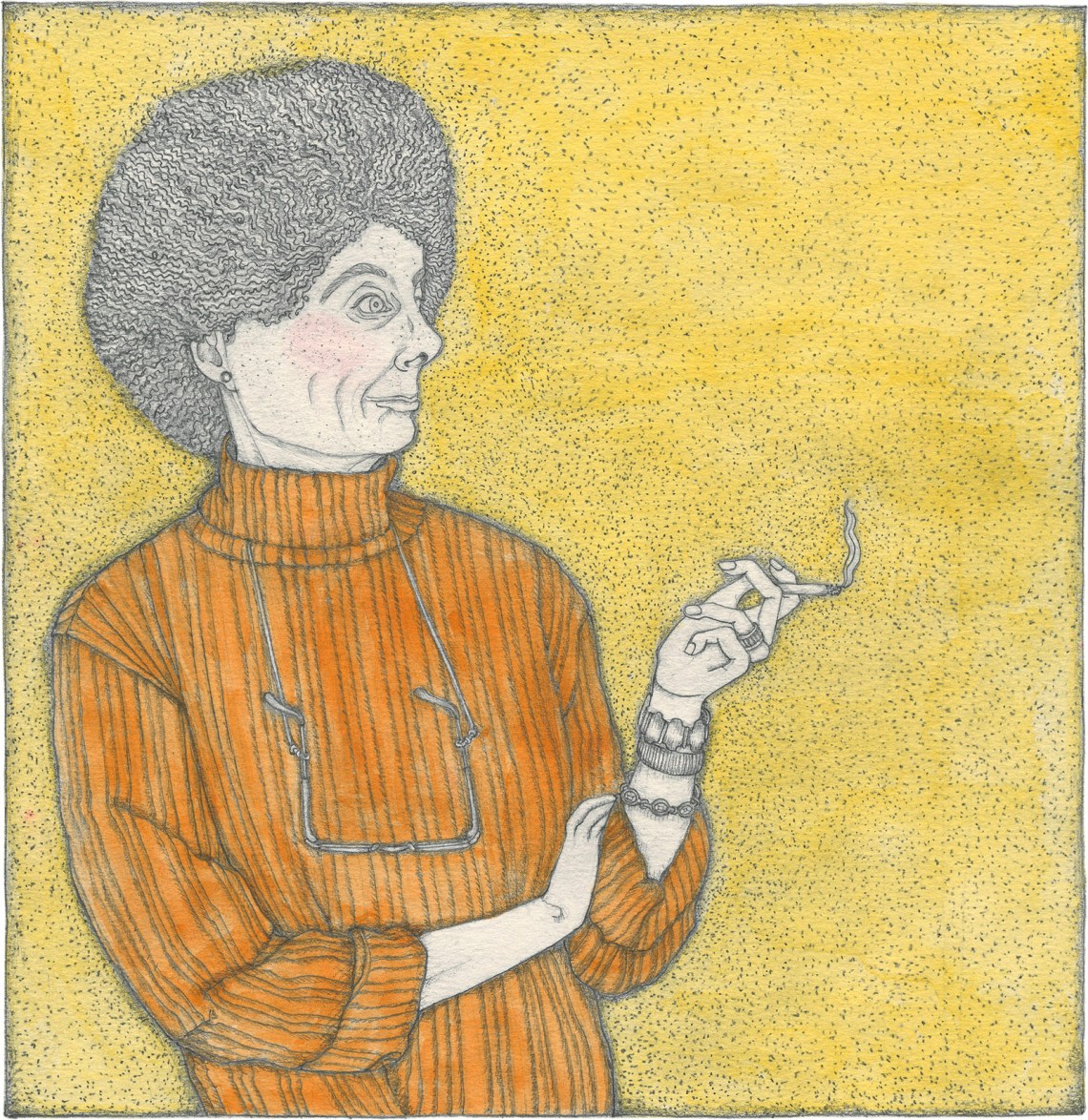

Harpman, who died in 2012 and was Jewish, was born in 1929 in Belgium, and her family fled to Casablanca when the Nazis invaded, though they returned after the war. Her medical training was cut short by tuberculosis, but much later she qualified as a psychoanalyst. She published her first novel in 1959, and Moi qui n’ai pas connu les hommes, published in 1995, was the first of her fifteen or more novels to appear in English.* The first English-language edition was published in 1997, under the title The Mistress of Silence, which, like I Who Have Never Known Men, is a phrase taken from the novel.

History’s bitter lessons for children of her times clearly informed Harpman’s view of life, but the world she depicts is significantly different from the one that threatened her, and its depredations appear possibly less dull-witted, one could say, and in a certain sense possibly less limited, than the ghoulish, blood-soaked inventions of the Third Reich. Despite their wholesale theft of Jewish property, despite their sadism and insatiable appetite for the humiliation of others, the Nazis’ ultimate objective was murder, pure and simple. That this objective was (thinly) veiled was only a matter of convenience.

In contrast, neither the extermination of particular demographics nor the elimination of particular individuals appears to be the basis of the political or economic ambition that culminates in the nightmare that Harpman’s characters are forced to endure. But the exact nature of that ambition is impenetrable. All that can be known is the scope of its architects’ ruthless exercise of power—an exercise that, whatever its objective, has served to dismantle rationality and meaning.

Paradoxically, the book’s austere mystery—the atrophied and gelid world it depicts—provides a richly allusive consideration of human life. It’s as if a sphere with a mirrored surface had dropped at our feet. We can’t see into it—it’s not a crystal ball and doesn’t seek to warn us in any literal way of a particularly plausible future, nor is it exactly a metaphor. What it offers are the extraordinary reflections that glide across it as it revolves. The Welsh novelist Sophie Mackintosh comments in her excellent afterword on this “prismatic” quality, as she calls it.

Speculative fiction tends to postulate one extreme social structure or another, into which writers let their characters loose to enact questions about relationships between the needs of individuals and the aims of a society: What benefits will one system or another confer on whom at the cost of what sacrifices to whom?

But no discernible social system whatever has landed these characters of Harpman’s in a cage, and what Harpman provides in her rigidly restricted frame is an arena in which to consider what is indispensable to the experience of being human—What do we need in order to be full human beings, to lead a good life?—and what crucial capacities of ours can be damaged, stunted, thwarted, or annihilated.

As everybody knows, books are animate and can go through metamorphoses, deaths, and resurrections during the lives of their readers—though it’s unpredictable what political or cultural developments, or what personal experiences, will bring a book flaring back to life or fail to, what will turn a book into a beloved companion or into a stranger.

As it happens, there’s a clamorous conversation between I Who Have Never Known Men and our current, very alarming moment. Probably no one can read the book now without feeling reverberations of the appetite for violence and retribution that is having a global resurgence on a scale not seen since Harpman was a young woman: of our reckless abuse of planetary resources; of the chilling harmony between, on the one hand, enthusiasm for capital punishment and, on the other, the movement to criminalize abortion—positions reconcilable only by the belief of certain people that they themselves should have power over life and death; of the prisons that are springing up like mushrooms, ostensibly to manage “social problems”; of the prevalent hostility toward reason and science and the associated degradation of education, to say nothing of the proposed militarization of schoolteachers; of our helplessness in the face of the current assault on sources of reliable information. Well, and obviously the list continues.

These are worries that swarm us as we wake up now, and all day long, and mostly through the nights, too. But over and above these contemporary horrors, I Who Have Never Known Men speaks to the eternal and existential: We’re here—now what? And come to think of it, what are we?

A piece of fiction could be said to succeed or fail depending on its credibility in one area or another. Judged by irrelevant criteria, I Who Have Never Known Men would certainly fall short in various ways. The meticulous and consistent detail that supports the imagined constructions of so much speculative fiction is lacking here—there are little inconsistencies, little repetitions, various features of its characters’ lives that aren’t really accounted for. The characters are for the most part indistinct, and little attention is paid to psychological verisimilitude, except in regard to the narrator.

But it all works. In the flat affect of the narrator’s clear prose, the swimmy vision moves and changes with the improvisatory practicality of a dream, and like a dream it seems to convey inarguable and urgent counsel in its coded, hyperreal images. It’s as if the author were waving aside trivial considerations and directing our attention, over and over again, to the fundamental, inescapable enigma of the book, and to the stupefying reality of human life itself—that our very existence comes with a proviso: a list of questions we’re compelled to ask that we cannot possibly answer.

The book suggests, repeatedly and in many ways, that perhaps our most essential quality is a void, an incompleteness—that what we need in order to be fully human is to sense something beyond our reach, a future, some possibility, something to be desired or learned or made or done or loved. And that it’s this sense of the something more that kindles imagination, longing, acts of mind—the experiences that enable us to feel human and make life worth living. “It only took me a month, which has perhaps been the happiest month of my life,” the narrator says about writing her memoir.

I do not understand that: after all, what I was describing was only my strange existence which hasn’t brought me much joy. Is there a satisfaction in the effort of remembering that provides its own nourishment, and is what one recollects less important than the act of remembering?

What might be powerful enough to counter the irrationality that is causing conscious beings to set about annihilating life? We can’t fly, we can’t live in the sea, but surely our capacity for the act of remembering, our capacity to desire, our capacity to imagine the chain unbroken, is just as precious, just as worth preserving. It still could happen that our species will spare itself and the planet that sustains us. But given the human-generated—and mutually fortifying—workings of climate change, zoonotic diseases, and war, as well as the other forms of violence we seem to find irresistible, it’s looking like a photo finish.

This Issue

July 21, 2022

A Painful In-Betweenness

‘She’s Capital!’

-

*

Harpman’s novel Orlanda has also been published in English, in a translation by Ros Schwartz (Seven Stories, 1999). ↩