When she was six years old, the cartoonist and graphic memoirist Alison Bechdel accompanied her parents and brother on a two-week trip to Europe. There, she experienced a “freedom from convention” that, she recalls, “was intoxicating.” Writing about the trip in her first book-length work, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, she explains how Europe’s looser mores provided a brief respite from the oppressive gender norms of American childhood. Bechdel speculates, however, that her parents had a very different experience: “While our travels widened my scope, I suspect my parents felt their own dwindling.” The page-wide drawing that accompanies those words depicts Bechdel’s father, paused mid-trudge in a busy airport, twisting around and urging her to “hurry up!” The child stumbles behind, lugging a large hard-sided suitcase with two hands. “This is too heavy!” she cries.

Bechdel is one of the foremost contemporary bards of family baggage. In her first two graphic memoirs—Fun Home and Are You My Mother?—she remembers how it felt to carry that weight: the strange family business (both parents were temperamentally bohemian yet got stuck running the family funeral home in rural Pennsylvania in addition to working as schoolteachers), her mother’s emotional distance, her closeted gay father’s suicide. Her parents’ artistic frustrations loomed large over Bechdel’s childhood; in another realization that accompanies the airport panel in Fun Home, she writes, “Perhaps this was when I cemented the unspoken compact with [my parents] that I would never get married, that I would carry on to live the artist’s life they had each abdicated.”

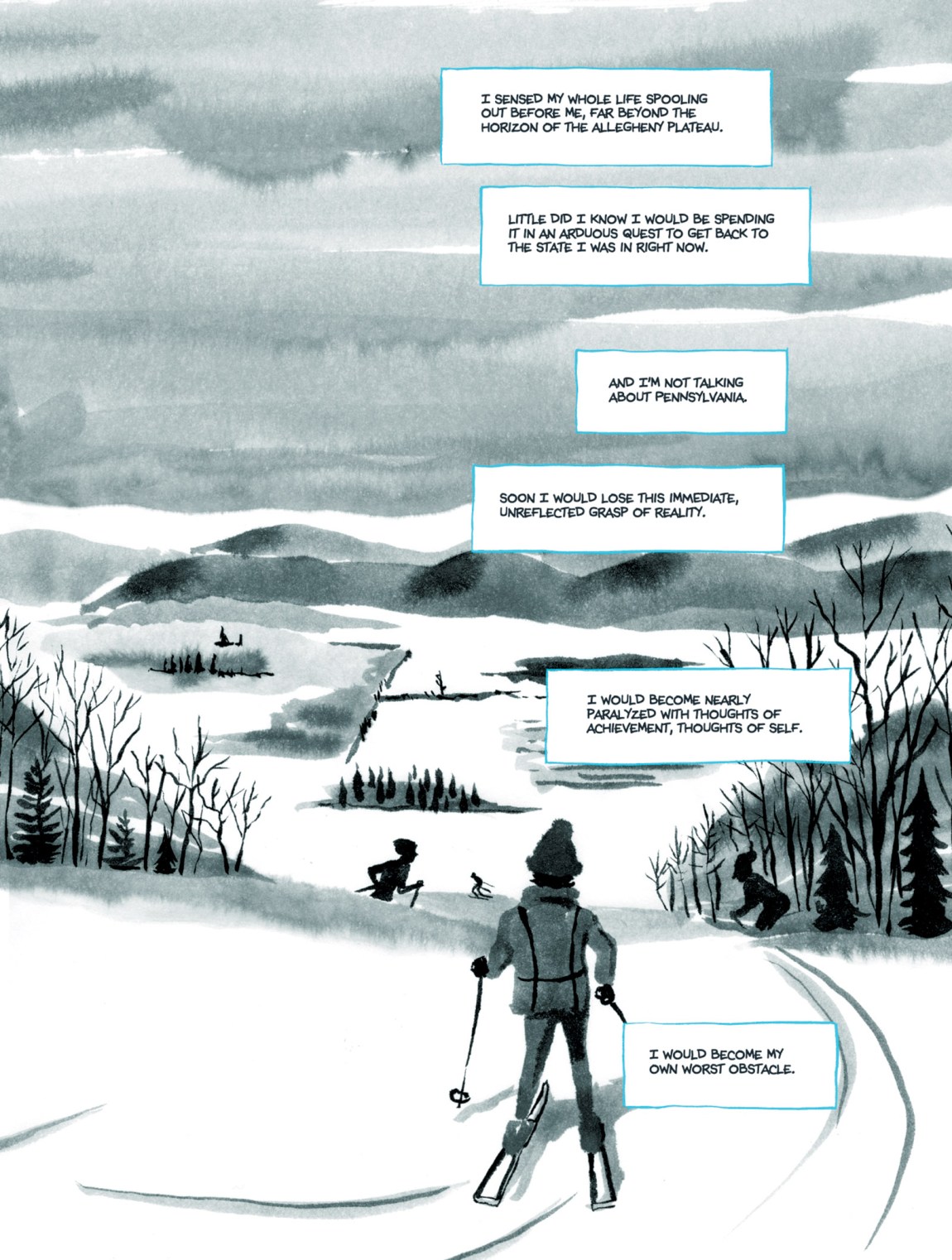

Bechdel’s most recent book, The Secret to Superhuman Strength, tells the story of the “artist’s life” she has lived in the decades since. Superhuman Strength is in many ways a classic Künstlerroman, a story about a person’s artistic development. But Bechdel uses a surprising conceit to explore her drive to create art: her lifelong obsession with exercise, fitness, and getting built. What does cardio have to do with art? Both, Bechdel suggests, are ways to escape the self. And both are (inadequate) answers to what turns out to be the animating question of the book: “How do we bear it?” As in, how do we bear the knowledge that we are going to die? Superhuman Strength accounts for how Bechdel has spent a lifetime trying to transcend her ego. In Bechdel’s hands, selfhood is presented alternately as an engine of creativity, a coping mechanism, and an obstacle to be overcome.

The Secret to Superhuman Strength is distinct from Bechdel’s previous work in a number of ways. While Fun Home and Are You My Mother? both feature complex, involuted timelines, The Secret to Superhuman Strength progresses through a mostly straightforward decade-by-decade chronology. While the previous books offer imagery only in black and white or muted wash, the images in Superhuman Strength pop off the page in a range of cartoonish colors. Unlike the more brooding, smaller-scale previous work, it’s big and bright, a bit goofy and chatty. (One of the first panels depicts Bechdel bent ass over teakettle and peering at us from between her legs—“Oh, hey! I didn’t see you there!”)

Yet there’s much that connects Bechdel’s books, which at this point compose a sort of Extended Bechdelian Cinematic Universe where characters, scenarios, and events echo and repeat, producing layered meanings. Superhuman Strength’s abstract philosophical questions about selfhood grow more meaningful if you’re aware of this layering. For example, returning in Superhuman Strength to the European vacation that she described in Fun Home, we find the child Bechdel, released from the family drama of the airport, now transported by the Swiss Alps. “In my feelings for the mountains there has always been a tinge of eros,” she notes. Next to a panel depicting the backs of Bechdel’s and her father’s heads, gazing on Mount Pilatus, Bechdel tells us, “I wanted that mountain. But—as would be true in the future of various human love objects—I couldn’t tell you exactly what I meant by that.” In Fun Home’s version of the trip, the child buckles under the weight of her father’s expectations. Here, however, Bechdel’s complex relation to herself, triangulated through her father, becomes a sublime spin on the idea of getting “swole”—physically enlarging oneself to the point of ecstatic self-dissolution. As the indie musician Will Oldham has put it, “If I could fuck a mountain/Lord, I would fuck a mountain.”

The Secret to Superhuman Strength has an almost Edenic narrative structure, tracing how Bechdel became exiled from the “blissful absorption” of her childhood and how she has tried to work her way back to that state ever since. Her pursuit of physical fitness has been central to this story. From childhood on, she found herself taking up sport after sport: skiing, running, martial arts, soloflex, yoga, hiking, biking, cross-country skiing, rollerblading, Alpine touring, the Insanity workout (!), the 7-Minute Workout, and back again, finally, to running. It’s hard not to identify with Bechdel’s tongue-in-cheek account of her obsession with various fitness fads, items purchased at Patagonia, and the strangely erotic space of the local bike store.

Advertisement

Absent from Bechdel’s story is any sense that her fitness obsessions were driven by the kind of pathologies that seem all too common among women. In an interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, who asked the author about “body image” and how damaging physical ideals did or did not factor into these obsessions, Bechdel said:

You know, I was very fortunate to come out into a very strong lesbian feminist subculture where I immediately was, like, deprogrammed of all the crazy female body image stuff I had picked up on during my teenage years—you know, all the worries about being too fat, all that craziness. Like, I had suddenly a political framework for it, and I could see how nutty that was. I’m very grateful that I had that experience.

Bechdel credits the queer feminist scene of the 1970s and 1980s and its political vision with helping her see, in her twenties, “that the body, so disavowed by the patriarchy, was not something separate or ‘other’” from the metaphysical idea of the self. In a two-page spread (in mostly black and white, the book’s visual indicator for “revelation happening here”) depicting an afternoon she once spent on mushrooms in Central Park, Bechdel narrates the self-alienated perspective in which, as she puts it, “I could see that my self—the self indicated by my driver’s license, encased in this skin, thinking this thought—was not real…. There was no self! There was no other.”

As the immediacy and drifting nonambition of youth give way to the satisfactions of exertion and achievement, Bechdel’s work comes to occupy a central place in her life. She presents this as both life-affirming and deeply antisocial. In her thirties Bechdel discovers mountain biking, quits her day job (as a production coordinator at the Minneapolis-based monthly gay and lesbian newspaper Equal Time) to devote herself to making art, and moves back east—“Not just east, but to that hotbed of enlightened, gaiter-wearing Transcendentalists—New England! Vermont had mountains built right into its name.” Living alone in a cabin in the woods, Bechdel spends her days riding up and down the Green Mountains and her nights working: “My increased endurance carried over into my work life.” She caroms between the “exultation” that results from both physical and mental exertion and “collapse”: “I was ‘free-running,’ a term I learned in an article about what happens to people’s sleep cycles when they live in a cave. I loved the feeling of being liberated from time.”

It’s during this tachycardic period that Bechdel’s creative work and physical drive come to be linked in a new way. As she began to work on what would become Fun Home, she devoted herself to getting strong enough to complete a pull-up. The achievement of this physical feat is depicted in a panel bisected by a pull-up bar that falls heavily across the picture plane, Bechdel’s face just barely clearing it and screwed up in pain, accompanied by the exclamation, “Entirely self-sufficient!”

Yet this form of self-sufficient liberation is ultimately revealed as false; Bechdel describes herself, in this era, as a draining and self-centered romantic partner, drinking too much (her passion for exercise was never of the clean-living, wellness sort so common now) and increasingly feeling the limitations of her body. As the chapter about her thirties comes to a close, we see Bechdel reach a nadir one sleepless night while paging through a copy of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces and coming across his citation of a line from the Katha Upanishad: “A sharpened edge of a razor, hard to traverse,/A difficult path is this—poets declare!” Bechdel recalls bursting into tears reading these lines, while also poking fun at herself as lightly histrionic for having done so. (“And come on, dark night of the soul? I was a cartoonist, for God’s sake.”)

The chapter closes with a panel that refers back to the “self-sufficient” pull-up bar panel that appeared two pages earlier; here, framed from a middle-distance perspective, Bechdel creeps up a staircase on all fours, her partner Amy following behind, hands gently steadying Bechdel’s bent lower back. “I have to change my life,” Bechdel says in a Rilkean speech bubble. “At last, I was able to sleep,” reads the text box under the panel.

Advertisement

The Secret to Superhuman Strength is suffused with belatedness, the sense that one is always coming too late even to one’s own life. Yet this melancholy feeling of forever-deferred clarity and calm, the book implies, is often confusingly yoked to a kind of determination, the idea that with just a bit more effort, just the right tweaks this way or that, a sense of integration—named variously throughout the book as “bliss” or “oneness” or “transcendence”—will arrive. The cyclical nature of these two contrary feelings—in which a person feels alternately broken and fixed, in a loop that never ends—constitutes the American religion of “self-improvement.”

Superhuman Strength traces this drive toward self-improvement not only in Bechdel’s own life, but also through a sprawling “lineage of progressive-minded writers…intent on some kind of inner transformation,” namely the English Romantics, the New England Transcendentalists, and the twentieth-century Beats. These writers guide Bechdel through the complicated history of how “inner transformation” comes to seem possible only through the opposed drives to both enlarge the self and, in doing so, to obliterate it. Bechdel describes Margaret Fuller having a “similar but non-drug-induced mystical experience” akin to her own Central Park revelation. Fleeing her tyrannical father, Fuller runs outside into the “free air” and realizes, as Bechdel writes, “There is no self!… It’s only because I think self real that I suffer.” A text box under a full-page illustration of the bonneted Fuller sitting in a wintry field reads, “It was this temporary transcendence of her self that would enable Margaret eventually to fulfill all her ambitions.”

Likewise, Bechdel see-sawed between instincts toward enlargement and erasure. As a child, she played two games in the bathroom mirror: in the first, she extended her arms outward so as to produce the visual illusion that her body was “of Atlantic proportions” and that her “shoulders went on forever.” But the second was a game of self-obliteration: in a rare closely framed self-portrait, Bechdel draws her memory of trying to stare in the mirror as a child in such a way as to “other” herself to herself, to dissolve her physical boundaries, thus inviting a “frisson of terror.”

Cartooning is an act of aesthetic distillation. As Bechdel put it in a 2006 interview with the scholar and critic Hillary Chute, “Everything in [Fun Home] is so carefully linked to everything else, that removing one word would be like pulling on a thread that unravels the whole sweater.” Superhuman Strength is no different, and reading it, I had a feeling that Bechdel’s work often inspires: not one thing is out of place in the world she has created on the page.

Yet coupled with the book’s linear chronology of the self, this quality feels a bit airless. The life story Bechdel traces is a little too neat, and this is most evident in the book’s chapter headings. Each spans two pages, across which Bechdel’s form unfolds at different stages of her life—first youthfully crouching, then skiing, back-bending, rollerblading, biking, and mountain climbing. In each image, she holds an enlarged inking or brush pen that traces the lines along which she travels, swooping and swirling around her figure.

When she is a child, the line makes neat, playful loop-the-loops. In her tween and teen years, the line effortlessly emerges from her graceful cross-country skiing strides. In her twenties, the line pops up and down, Bechdel’s figure perched in unconscious youthful strength atop its tiny peaks. Her thirties show the artist in deep focus, head bent to the liquid lines she draws while rollerblading across the surface. It’s in her forties that things start to feel tough, the figure’s effort to both create and experience looking more obvious as she holds on tighter and tighter to the line, yanking it up toward her and continuing to climb even while her strength dwindles.

I found these chapter headings by turns painfully relatable and totally alienating, precisely because they are so intentionally relatable. As Bechdel ages, the struggle gets deeper and simpler at the same time. The last two chapters rush headlong toward an ending that is quite gorgeous and, like her “I have to change my life” revelation, somewhat clichéd. Struggling to find a way to finish the book, Bechdel finally lands on a solution after dunking her head under an icy waterfall, a way of attaining creative enlightenment that she’d discovered years before:

I could see that I’d been deriving a kind of “happiness” from the unhappiness of struggling to finish the book…. Because I didn’t want it to end. Just like I didn’t want my life to end. But my life was going to end. What if the point was not to finish, but to stop struggling?

It’s a peaceful ending, with Bechdel finally reaching a form of enlightenment—“Nirvana is samsara, I finally got the memo. Onward to the grave!”—in a beautiful, cold, and wintry wooded scene bisected by a brook flowing diagonally across the double-page spread. We’ve seen rivers, creeks, springs, and brooks in Bechdel’s work before. Earlier in The Secret to Superhuman Strength, the child Bechdel stands abashed on her cross-country skis before a river swollen and violent with floodwaters. In Fun Home, readers encounter creeks with snakes in them, or ones that have become disturbingly crystalline, lacking in organic life because of acidic mine runoff. On the last pages of The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Bechdel and her partner Holly stand in the woods beside the brook—depicted as deep, abundant, and flowing—chickadees literally alighting on their hands. Bliss has finally arrived.

Or has it? When I looked a little closer I saw that the chickadees Holly had trained to land on her weren’t actually landing on Bechdel’s open palm—not on this page or the other that describes their endeavor to train the birds. This final image of Bechdel looking expectantly upward is in tension with the narration’s assertion of closure. This is a thread worth pulling on, which might take a reader back to another temptingly frayed moment that occurs when Bechdel is about to turn forty and beginning to stare down her mortality. She visits a Buddhist meditation center and confesses to her guide, “I hate sitting with other people. They’re all doing it right, and I’m not.” She sits cross-legged, with arms also crossed, eyes staring, a closed-off figure. When he gently responds, “Well, then that’s your next step. You need to come sit with the group,” she leaves and, the text box tells us, “To this day, I have not been back.”

The comment is an eruption out of the neat narrative chronology of the book into a continuing present, this particular self-improving task left undone, as far as I can tell, forever. The specters of climate change, authoritarianism, the pandemic, and global collapse run through the background of the last two chapters of The Secret to Superhuman Strength—often blaring out of a TV set or radio or newspaper while Bechdel mostly goes about her life—an illustration of interconnectedness that, like the chapter headings, feels both relatable and alienating. For those of us who live mostly secure lives, these specters reside in the background, our experience of ourselves constantly foregrounded. Yet many resources are getting scarcer, and “the self” is likely one of them. Our time of transcendence may be rapidly coming to an end.