In Damon Galgut’s 2010 novel In a Strange Room, a group of backpackers are walking along the shore of Lake Malawi. They’re the kinds of tourists who refer to themselves as “travellers,” in search of what they believe to be the authentic African experience, and they think they’ve found it at Cape Maclear: “This is the real Africa to them, the one they came from Europe to find, not the fake expensive one dished up to them at Victoria Falls, or the dangerous frightening one that tried to hurt them on the train.” The newly formed group includes some Scandinavians, an Irishwoman, and a couple of English people, and they’re all thrilled with one another, tossing about nicknames and day-old in-jokes.

The latest addition, like the author a white South African named Damon, is not what you’d call a joiner: “He’s the odd one out here, he keeps a distance between himself and them, no matter how friendly they are.” As they walk down the beach, Damon overhears a conversation between a Swedish woman and a Danish man. The woman asks the man how he enjoyed his recent trip to South Africa, and, unaware that Damon is listening, the man replies that of course it was very beautiful, “if only all the South Africans weren’t so fucked-up.” In this moment, Damon stands outside himself and watches, as he does periodically: “Then everyone becomes aware of him at once and silence falls, of all of them he is the only one smiling, but inwardly.”

A few days later, the group decides to hire a boat and go to one of the islands. For a small fee, they conscript a Malawian to row them out there and let them use his goggles and flippers, which are among his few possessions. The European tourists don’t register that the price of the flippers “is worth maybe a week or two of fishing to this man,” and manage to lose one between the rocks. They don’t care—“Let him buy a new one”—but Damon does, and he harangues them until they all get out of the boat to look for it:

In the end the flipper is found and everybody gets back into the boat and in a little while the frivolous conversation resumes, but he knows that his outburst has confirmed what they suspect, he is not the same as them, he is a fucked-up South African.

The condition of being a South African—and specifically a white South African—is a recurring theme in Galgut’s books.* In The Good Doctor (2003), set shortly after the country’s first democratic election, in 1994, two white physicians work at a desolate, understaffed hospital in a former apartheid homeland—one of the derelict stretches of countryside that the white minority government designated for black South Africans from the mid-twentieth century onward after forcibly removing them from their homes and stripping them of their citizenship. “On one side was the homeland where everything was a token imitation. On the other side was the white dream.” The younger physician, Laurence, is an idealist who believes that the recent election represents a bright, uncrossable line between the past and the present: “The old history doesn’t count. It’s all starting now. From the bottom up.”

The older physician, Frank, believes that he knows better. He was previously a field doctor in apartheid South Africa’s war against the liberation movements on its borders, and the morally warping decisions he made then have become “the dead centre” of his life. The self-deceptions he has developed in order to manage the flashbacks that haunt him have made him cynical. He tells himself that a liberation fighter being interrogated under his watch was going to die no matter what he did, and anyway that man was the enemy, and what was he, Frank, meant to do? Where Laurence sees the possibility of change, Frank sees the inevitability of everything staying more or less the same, with apartheid-era bureaucracy still in place at the hospital and apartheid’s economic and spatial legacies visible out of every window. The novel memorably demonstrates the ways in which each man is wrong.

In The Impostor (2008), Adam, a white South African poet, retreats to an isolated town in the Karoo after failing to thrive in a Cape Town full of property developers exuberantly capitalizing on what was always referred to as the “business-friendly environment” of the postapartheid years. As in The Good Doctor, the protagonist is confronted with his opposite: where Adam is aloof and bewildered, Canning is an outgoing entrepreneur, primed to see opportunity in the cracks opened by corruption. Once more, the contrasts between the two men expose the contradictions of a society that somehow keeps holding itself together.

Advertisement

Galgut’s characters are often loners in flight from something, fixated on the idea of a fresh start yet shaped by a past that makes a joke of new beginnings. He writes about complicity, complacency, and compromise, moral bankruptcy and inertia, the speed with which entitlement shifts into resentment and then into viciousness. Often he writes about anger, either turned against the self or turned against others: “Something in this country had gone too far, something had snapped. It was like a fury so strong that it had come loose from its moorings.”

All of this is on riveting display in The Promise, which won the Booker Prize last year and is Galgut’s most ambitious novel to date. It begins in 1986, one of the bloodiest periods of the apartheid era, when the white minority government imposed a state of emergency in an attempt to obliterate internal resistance. It closes in early 2018, when President Jacob Zuma resigned after a series of corruption scandals: “A quick statement, then he’s walking away…. After holding us to ransom for years and years, he just lets go and strolls out.” Galgut carefully tracks the country’s transformation from the nadir of the apartheid era to the optimism of the Mandela presidency and then to the demoralization of what is sometimes referred to as the post-postapartheid era.

The novel opens with the death of Rachel Swart, matriarch of the half-Jewish, half-Afrikaner Calvinist Swart family, and the summoning of her three teenage children—Anton, Astrid, and Amor—to the funeral. Anton, nineteen, has been doing his compulsory military service—as all white South African men, including Galgut, were obliged to do until 1994—and has just murdered a black woman while putting down a township protest: “He used the rifle yesterday to shoot and kill a woman in Katlehong, an act he never imagined committing in his life.”

After the funeral, Anton begins to argue almost lazily with his father, Manie, who tips unexpectedly into rage: “What is wrong with you?… What is wrong with all of you? Pa shouts, then gets up, for some reason with difficulty, and walks off on stiff legs into the garden, bellowing incoherently.” These questions could be said to propel The Promise’s depiction of this dysfunctional family: What’s wrong with all of them? The novel takes its epigraph from Fellini:

This morning I met a woman with a golden nose. She was riding in a Cadillac with a monkey in her arms. Her driver stopped and she asked me, “Are you Fellini?” With this metallic voice she continued, “Why is it that in your movies, there is not even one normal person?”

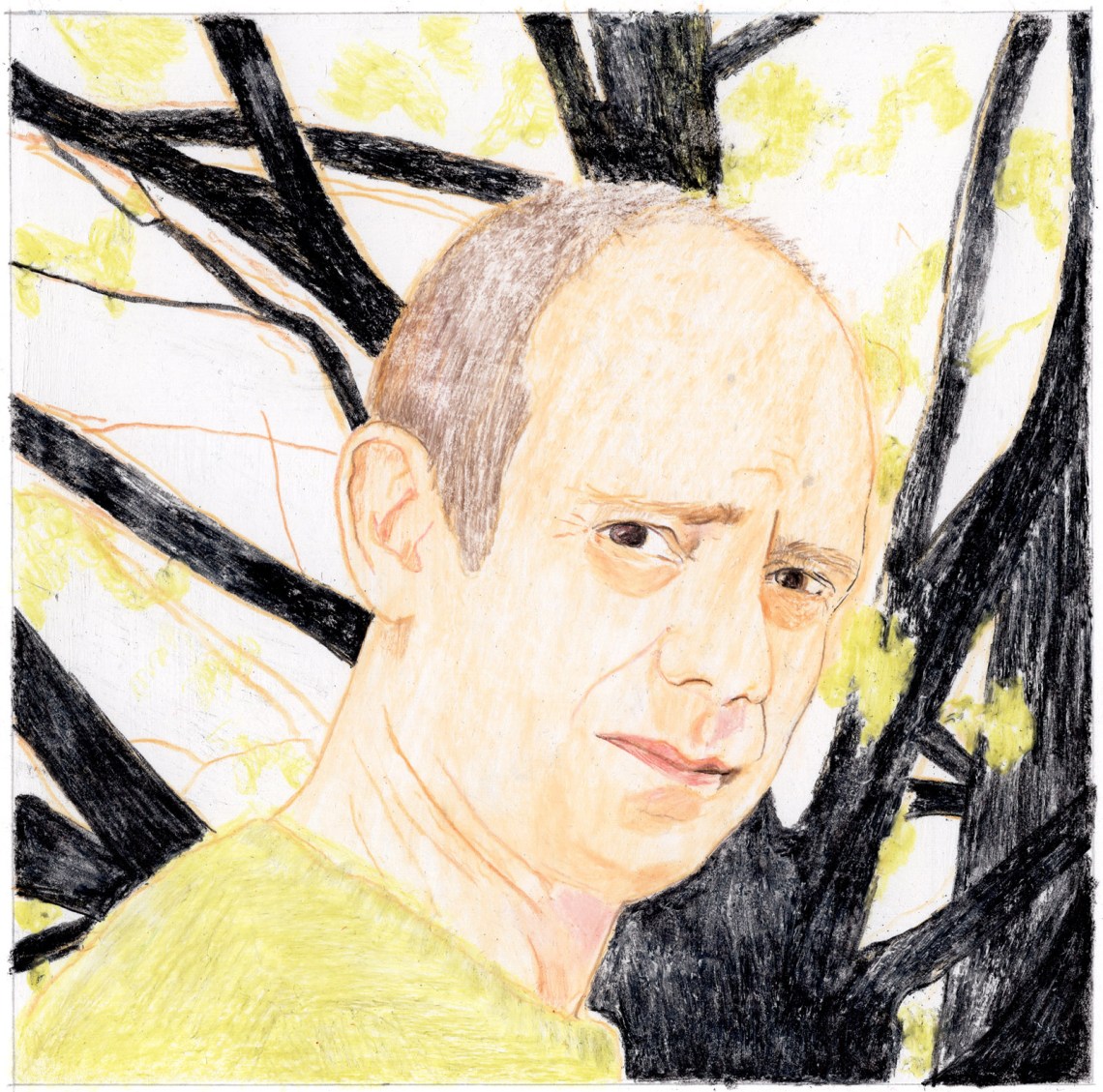

In a recent interview, Galgut described The Promise as “my South African novel,” a statement that may seem odd at first, coming from a South African novelist who writes about South Africa. Galgut was born in 1963 and grew up in Pretoria, the capital of the apartheid state; he now lives in Cape Town (where I’ve spent most of my adult life). Couldn’t most or even all of his work be described as South African? The Promise, though, is different from his other books. It’s more specific in its depictions of this starkly divided society, more direct in the way it approaches what has always been the country’s most significant political issue, its central injustice: the land and whom it belongs to.

The novel is divided into four sections, each of which centers on the death and funeral of a member of the Swart family: first the parents, Rachel and Manie, and then two of the children, Astrid and Anton. The Swarts are white, and the fact that their name means “black” in Afrikaans could be viewed as an unsubtle bit of ironizing on Galgut’s part, but it’s also a common surname, and South Africa is not a subtle place.

The book’s title derives in part from a conversation that thirteen-year-old Amor overhears between her parents as she hides in the shadows of the room where her mother is dying. “I really want her to have something,” Rachel says. “After everything she’s done.” Rachel doesn’t say whom she means, but Amor believes she can only be referring to Salome, the family’s longtime domestic servant, who partially raised Amor and her siblings and looked after their mother through her illness, doing

all the jobs that people in her own family didn’t want to do, too dirty or too intimate, Let Salome do it, that’s what she’s paid for, isn’t it? She was with Ma when she died, right there next to the bed, though nobody seems to see her, she is apparently invisible.

The promise, as Amor understands it, is that her father will give Salome legal ownership of the small house she has lived in ever since anybody can bother to remember. “My grandfather always talked about her like that,” Amor thinks: “Oh, Salome, I got her along with the land.”

Advertisement

Salome’s house means nothing to Amor’s born-again Christian father, who is far more preoccupied by his wife’s baffling request to be buried according to Jewish tradition, a demand that he perceives as a final attempt to torment him. The house holds no importance for any of the Swart family, in fact. It’s just an ugly little tumbledown thing on the edge of their farm—“three fucked-up rooms with a broken roof”—in contrast to their own “big mishmash of a place, twenty-four doors on the outside that have to be locked at night.” More perceptive than the rest of her family, Amor sees what this promise will mean to Salome. Just after her mother’s death, Amor tells Salome’s son Lukas—who like Amor is thirteen years old—about what she’s heard (or thinks she’s heard), assuring him that her father will make good on his promise, because “a Christian never goes back on his word.”

What Amor doesn’t know is that her father could not bestow legal ownership of the house to Salome even if he wanted to, which he very much does not. The law will not allow it, just as the law will not allow Salome to vote or hold citizenship in the country of her birth. And so all that Amor’s mother can do for Salome is make an apparently well-intentioned gesture and hope that her wishes will be carried out, as if good intentions and an acknowledgment that imbalances should be redressed are adequate compensation for decades of dispossession.

Amor presents the house to Lukas as if it is the answer to his prayers, the way it is for his mother. It doesn’t look like that to Lukas at all: “It’s always been his house, he was born there, he sleeps there, what is the white girl talking about.” The questions of the house, whom it belongs to, whom it should belong to, and whether the Swarts had any business thinking it was theirs to give away in the first place—as well as whether they intended to give it away at all—are repeated and reframed throughout the novel, appearing newly complicated and more pressing in each section.

Galgut’s decision to structure the novel around the deaths and funerals of the four Swarts is ingenious, allowing for almost lurid insights into the tenor and mood of four different moments in the country’s history. Manie, who owns a successful reptile park, Scaly City, dies in 1995, one year into Mandela’s presidency, in a hospital that still bears the name of the architect of apartheid, Hendrik Verwoerd. His death is caused by a snakebite after he attempts to break the world record for living among poisonous snakes in an effort to raise funds for the prosperity-gospel church recently erected on a corner of the Swart family farm. This might seem fancifully macabre, but such parks are common—one out of every three of my own primary school field trips was to a disgusting reptile zoo called Snake Park—and if you ask a South African old enough to remember the explosive popularity of evangelical churches during the 1990s, particularly among white South Africans fretting about their declining status in a country where everyone now had the vote, the manner of Manie’s death reads as emblematic of the era.

The Promise derives much of its strength from Galgut’s remarkable ability to shift frictionlessly between multiple perspectives. Manie’s funeral is held on the day that the South African rugby team won the 1995 World Cup—a moment of giddy “postracial” optimism that Galgut presents as both utterly sincere and utterly naive—and the victory is presented through the eyes of all the incredulous white South Africans who did not believe such a moment was possible:

And nothing will ever, ever be better than this moment, with everybody jumping up and hugging each other, strangers celebrating in the streets, cars hooting and flashing their lights.

But then it does get even better. When Mandela appears in the green Springbok rugby jersey to give the cup to Francois Pienaar, well, that’s something. That’s religious. The beefy Boer and the old terrorist shaking hands. Who could ever. My goodness.

Galgut’s ear for the stunted rhythms of white South African speech—“an accent squashed underfoot, all the consonants decapitated and the vowels stove in. Something rusted and rain-stained and dented in the soul, and it comes through in the voice”—intensifies the contrast between a highly charged, complex political moment and the inadequate attempts, on the part of many of the white characters, to understand it: “South Africa! The name used to be a cause for embarrassment, but now it means something else. Truly, we are a nation that defies gravity.”

What a cynic would describe as the laws of physics have started to reassert themselves by the time Astrid’s funeral takes place nine years later, around the time of Thabo Mbeki’s second inauguration—a time of relative unity and investor-friendly prosperity, but also one of the darkest moments of the AIDS crisis, with the president denying any link between HIV and AIDS, and 30 percent of pregnant women infected with the virus. Such information is presented not directly but through glancing, sideways observations, the operatic extremes of South African reality played through a tinny household radio.

Anton calls Amor off her shift at an HIV ward in Durban to tell her that their sister has been murdered in a carjacking: “He speaks out of the air from a long way off, somewhere in the past, only to her, in the nurses’ station, its tiles as white and cold as shock.” Anton is informed of the circumstances of Astrid’s death by two jaded policemen, in a passage that will land with sick familiarity on anyone who has ever opened a South African newspaper:

This murder? This one is nothing. You should’ve been with me only last week. Oh boy, things I could tell you. Any reason will do. South Africans kill each other for fun, it sometimes seems, or for small change, or for tiny disagreements. Shootings and stabbings and stranglings and burnings and poisonings and smotherings and drownings and clubbings/wives and husbands slaughtering each other/parents offing their children or the other way around/strangers doing other strangers in.

Violence lurches through the novel almost as a character, sometimes asserting itself in bald terms, as in the passage above or when Anton shoots and kills the unnamed woman in Katlehong or when we see hints of an unspeakable ugliness, as in this scene involving Anton and a morgue employee: “Have you seen a dead body before? Savage asks him, from the other side of the table. His tone is without relish, but don’t let that deceive you, Savage has his predilections.” Earlier in the novel, Anton visits the family doctor after being wounded by a stone thrown at him through a car window as he drives through Atteridgeville, a township very much like Katlehong:

Dr. Raaff wields his tweezers with more-than-usual dexterity, he and the instrument are suited…. His fastidiousness is pleasing to his patients, but if they only knew the daydreams of Dr. Wally Raaff, few would submit to being examined by him.

The cumulative effect is of crawling dread.

Most of Galgut’s characters have something violent to say—but not Salome. In this polyphonic novel, where almost everyone else’s inner monologue is heard out, she is silent, or silenced, invisible to most of the white characters even as she stands right in front of them, even as the scale of her dispossession and betrayal becomes apparent to those who have pretended not to see it:

A stout, solid woman, wearing a second-hand dress, given to her by Ma years ago. A headscarf tied over her hair. She is barefoot, and the soles of her feet are cracked and dirty…. Same age as Ma supposedly, forty, though she looks older. Hard to put an exact number on her.

What the house means to Salome is touched upon here and there: “She has thought of nothing else since the words were spoken. To have her own house, to hold those papers in her hand!” But as the years march on and the Swarts steadfastly maintain their grip on it, her feelings must largely be inferred. There is a devastating passage early on in which an omniscient authorial voice speculates on Salome’s thoughts as she prays for Rachel, whom she cared for intimately and whose funeral she is not allowed to attend:

She sits out in front of her house, sorry, the Lombard place, on a second-hand armchair from which the stuffing is bursting out, and says a prayer for Rachel.

O God. I hope You can hear me. It is me, Salome. Please welcome the madam where You are and look after her carefully, because I wish to see her again one day in Heaven…. I am sure You understand because it was You who gave this great suffering to her, so that I could look after her. For that she promised this house to me and for that I thank You. Amen.

Perhaps she doesn’t pray in these words, or in any words at all, many prayers are uttered without language and they rise like all the rest.

This is one of the only spots where Galgut invites the reader even to imagine the thoughts of this woman whose life has been defined by betrayal. The decision not to have given her more of a voice is a risky one. On the one hand, Salome’s muting can be interpreted as directly mirroring a country where the voices of poor black women remain ignored, and where the promise that their lives would be materially different after apartheid remains largely unmet. On the other hand, the refusal to represent the point of view of this utterly dispossessed woman can look, in certain lights, like a failure of nerve on the part of a middle-class white author, a reluctance to commit the thoughts of such a character to paper.

An argument against this latter interpretation, however, can be found in the novel’s final pages, when—after Anton’s death—Amor goes to Salome’s house to make good on the promise at last, and she and Lukas resume the only conversation that has ever really mattered in South Africa. “And still you don’t understand, it’s not yours to give,” Lukas says.

It already belongs to us. This house, but also the house where you live, and the land it’s standing on. Ours! Not yours to give out as a favour when you’re finished with it. Everything you have, white lady, is already mine.

There is no resolution, no precise point at which it is obvious that things would have gone differently had other decisions been made. The Promise’s power lies in its measured, exacting, occasionally cruel depiction of the way the land question has irretrievably warped almost every character in the novel, whether or not they are capable of acknowledging it.

-

*

A notable exception is Arctic Summer (Europa, 2014), his fictionalized biography of E.M. Forster. ↩