Every great city is a constant act of reinvention. Fashionable new structures rise over the wreckage of unfashionable older ones. Neighborhoods change character and function. Populations and industries ebb and flow. Hidden from sight, underground infrastructure spreads like a living thing, fiber-optic cables unspooling where pneumatic tubes once ran. New modes of transportation come on the scene. Businesses discover ever more garish ways to seize the attention of passersby.

Paris has been a great city in this sense for a very long time. Baudelaire’s lament that “old Paris is no more (a city’s form changes faster, alas, than a mortal’s heart)” would have rung true at almost any time in the past five or six centuries. Still, Paris has differed strikingly from other great cities in at least two respects. One is its size. With a formal surface area of less than forty-one square miles, it is less than an eighth the size of Berlin, barely a fifteenth that of London. Even Brooklyn outsprawls it by nearly three quarters. A leisurely stroll across its central arrondissements, from the place de l’Étoile in the west to the place de la Bastille in the east, takes less than an hour and a half.

Second, perhaps nowhere else in the world has a city’s reinvention owed so much, for so long, to the heavy-handed action of the state. Again and again, for centuries, the rulers of France have tried to remold their recalcitrant capital, striving to make it more salubrious and beautiful, more orderly and efficient, wealthier (and more reliably taxable), and less prone to rebellion. They have erected walls around Paris and taken them down, built new streets, squares, monuments, institutions, museums, transportation hubs, parks, bridges, and hidden infrastructure. They have kept under strict control what private individuals and companies can build, and where, and how. Tourists may sometimes perceive Paris as an unchanging museum, but within living memory so much of it fell under the wrecking ball—including the grand old central marketplace of Les Halles—that in 1977 the historian Louis Chevalier published a diatribe entitled The Assassination of Paris. During François Mitterrand’s presidency, from 1981 to 1995, the French state gave the city a massive new opera house, finance ministry, national library, and monumental “Grande Arche,” not to mention a redesigned Louvre, the Arab World Institute, and the science museum and other facilities at the Parc de la Villette.

Today Paris shows signs of a new sort of transformation for which its small size makes it ideally suited: liberation, at least in part, from the grip of motorized vehicles. Last year the administration of Socialist mayor Anne Hidalgo permanently closed a two-mile stretch of highway along the Seine, transforming it into a lovely pedestrian promenade. Plans for a zone apaisée (calm zone) will further restrict vehicle traffic in the city center. And after the 2024 Paris Olympic Games, the city hopes to permanently close lanes in its traffic-choked beltway while planting 70,000 trees along the route in a new “green belt.” Bicycle use in the city, which fell drastically in the 1950s, has rebounded impressively in the past decade.

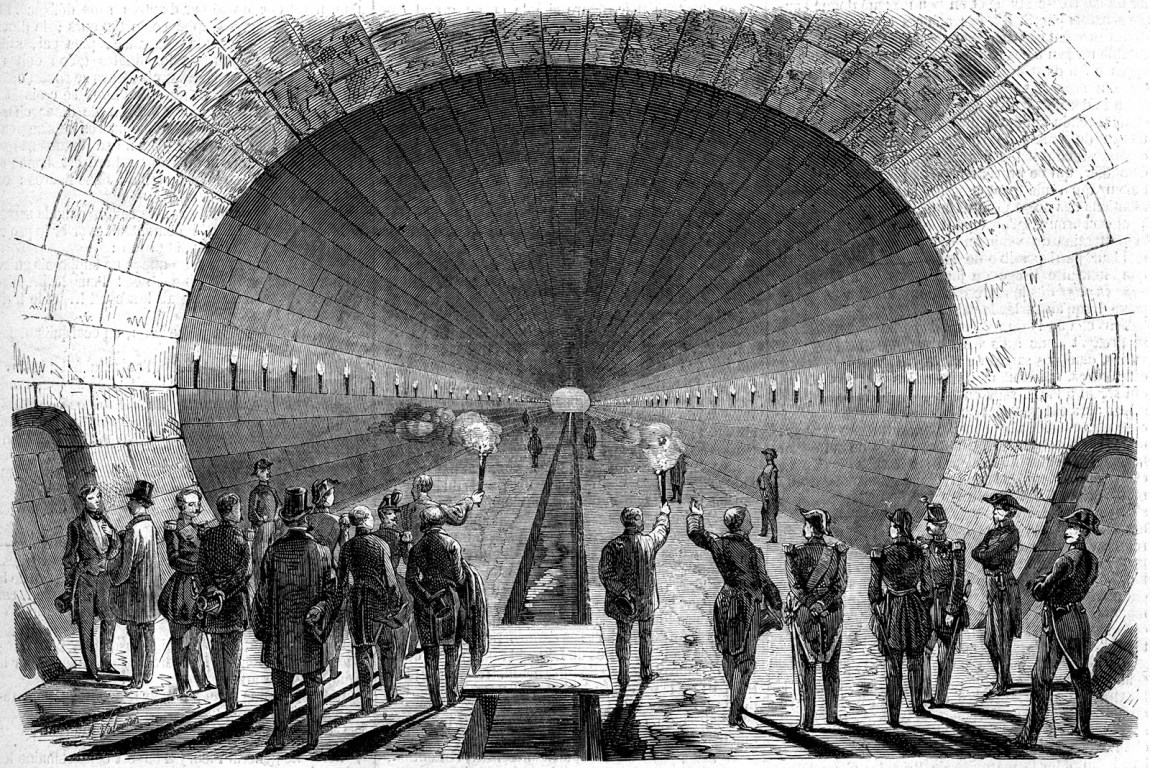

These recent changes, however, cannot compare with those from the most famous and dramatic period of reinvention in the city’s history: the Second Empire of Napoleon III and his prefect of Paris, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. In the 1850s and 1860s they undertook a huge project of urban renewal. Most strikingly, they plowed broad new boulevards through the heart of the city, demolishing old neighborhoods in the process. They built large squares and cleared out space in front of monuments such as the Cathedral of Notre-Dame. They more than doubled the size of Paris, annexing what had been separate villages such as Montmartre, Passy, Charonne, and Belleville. On the edges of the new metropolis they built enormous parks, including the Bois de Boulogne and the Bois de Vincennes. They developed impressive new infrastructure, including gas lines for street lighting, pneumatic tubes for documents, street paving, aqueducts, and a sewer system so monumental it became a tourist attraction. They continued older reform projects, including the emptying out of the communal graveyards and the reburial of centuries of Parisians—ultimately more than six million people—in the underground tunnels and quarries of the Catacombs.

Even areas of Paris that the Second Empire apparently overlooked bear its marks—or scars. The Luxembourg Gardens lost a third of its area during the period, while one of its most popular attractions, the Médici Fountain, was packed up and moved to a new location in the gardens. Haussmann lowered the bed of the Canal Saint-Martin and covered part of it with what is now the boulevard Richard-Lenoir (originally the boulevard de la Reine Hortense, named after the emperor’s mother). He also rebuilt much of the Palais de Justice on the Île de la Cité, tearing down a large medieval gallery, adding a neo-Gothic façade, and obscuring the exterior of the Sainte-Chapelle. (“You have hidden…this beautiful reliquary,” one observer expostulated in 1856, “in the bottom of a pit.”)

Advertisement

It is no wonder, in short, that “Haussmannization” has become a virtual synonym for urban transformation, and that cities around the world have explicitly followed the nineteenth-century Parisian example. In South America, both Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires were rebuilt along Haussmannian lines. The Second Empire partly inspired Robert Moses in his projects of dubiously creative destruction, while the French architect and planner Le Corbusier dreamed of going further than Haussmann and rebuilding Paris without streets at all.

To a great extent, this gigantic bout of urban renewal had its origin in fear. Napoleon III knew very well that at many moments in the past, Parisian rebellions had led directly to the overthrow of French rulers, or had come close, including four times in just the quarter-century before he seized power. Before Haussmann, it took little time for insurgents to plug the narrow streets of the old city center with barricades built out of overturned wagons, spare lumber, barrels, trees, and cobblestones. Meanwhile, horrific cholera outbreaks in 1832 and 1849 called new attention to the ease with which disease spread in a city desperately lacking in fresh water and sewers, where human waste flowed freely down gutters running in the middle of streets. Crime, luridly reported on in the daily press and in popular novels, remained a perennial problem.

To cosmopolitan bourgeois like Haussmann, the Parisian underclass seemed dangerously alien. The novelist Eugène Sue called its members “barbarians, just as foreign to civilization as the savage hordes so well depicted by [James Fenimore] Cooper.” The French government expelled working-class Parisians from the city center to the newly annexed periphery or beyond, into what remain poor, crime-ridden banlieues. New corridors like the boulevard Saint-Michel and the boulevard de Sébastopol provided easy access for mounted troops, while their impressive width was meant to deter all but the most ambitious barricade builders. The emperor also boasted that replacing cobblestones with macadam (named for the Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam) would deprive those barricade builders of at least one favored construction material.

The projects drew on many earlier precedents inspired by the same perennial fears. The replacement of narrow warrens of streets in the city center with open, airy spaces dated back at least as far as Henri IV’s construction of the place Royale (now the place des Vosges) and the place Dauphine in the early seventeenth century. Even after Henri’s descendants moved their residence and capital to Versailles—in part out of terror of Parisian revolt—renewal continued, notably with the creation of the vast place Louis XV, now the place de la Concorde.

During the French Revolution, an official committee of artists, architects, and engineers drafted an ambitious plan that foreshadowed the Second Empire’s in many respects. Its authors insisted on the need to remove the “foci of infection and unhealthiness that one finds” in the city. Haussmann and Napoleon III also drew on work done by Haussmann’s predecessor Count Rambuteau during the July Monarchy of 1830–1848. Scholars now emphasize that Haussmann was not the master planner of legend (a legend propagated by his self-serving memoirs) but relied heavily on plans drawn up by a committee headed by Count Henri Siméon.

If the Second Empire’s remaking of Paris dwarfed all previous—and all subsequent—efforts, it was primarily for two reasons. The first, not sufficiently appreciated by many historians, is that Napoleon III presided over one of the most powerful states in French history. Even today, two memorable insults hurled at the emperor make it hard to take him seriously: Victor Hugo’s devastating sobriquet “Napoléon le Petit” and Marx’s withering apothegm that his seizure of power in 1851 was a “farce” compared with the “tragedy” of his uncle Napoleon I’s coup. An eccentric who came to high office almost entirely on the basis of his famous name, after having failed pathetically in two early coup attempts, Napoleon III counted no great military exploits to his name and lost his throne after the nation’s catastrophic defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, in which he was taken prisoner. But at home he had an efficient machinery of repression, a formidable state administration inherited from earlier rulers, and backing from the army as well as from much of the peasantry and social elite. While the regime liberalized in the 1860s, it was in large part a controlled, cautious liberalization from above. In short, in remaking Paris, Napoleon III could count on extensive resources and on opposition remaining muffled and ineffective.

Advertisement

The second reason was capitalism. As scholars such as François Loyer and David Van Zanten have emphasized, the rebuilt city nicely served the purposes of capitalist entrepreneurs.* The broad new boulevards facilitated commercial exchange. Attractive sidewalks and arcades, brilliantly lit even in the winter gloom thanks to new gaslights, drew shoppers to consumer emporia, reinforcing the city’s reputation as the world capital of fashion. Builders, happily following standard designs prescribed by the state, made fortunes constructing luxurious office blocks, stores, and apartment buildings, especially in fashionable neighborhoods such as the precincts of the new Opéra Garnier. Indeed, virtually all the facets of Second Empire urban renewal offered opportunities for profit, as the government leased out control over water mains, telegraph lines, steam pipes, gas lines, and much else. Figures close to Haussmann and the emperor made quick fortunes from insider information about which neighborhoods had been slated for demolition and rebuilding.

Historians have long held conflicted views about this episode in urban history. On the one hand, they find it hard not to express outrage at the brutal treatment of the working poor, the demolition of old neighborhoods and monuments, the corrupt speculation, and the unabashed commercialism. Yet at the same time, it is hard not to feel appreciation for the final product: the vibrant and elegant city center that remains one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world, with more than 19 million visitors in the last year before the pandemic. Whatever the human cost of its creation, the Paris of Haussmann and Napoleon III was a work of art.

Esther da Costa Meyer’s fascinating and sumptuously illustrated Dividing Paris fully reflects this conflict. Her title breathes disapproval, and she devotes considerable space to the forced removal of the urban poor from the city center to shabby, crowded, and dirty peripheral neighborhoods that had none of the amenities enjoyed by the bourgeois of the new boulevards. She also highlights the “brutal erasure of countless landmarks.” With the keen eye of an expert architectural historian, she demonstrates how even an apparently innocuous reform, such as the clearing out of the congested neighborhood around Notre-Dame, was actually impoverishing:

Gone was the straggle of streets that withheld the view of Notre-Dame until the last moment, heightening the element of surprise. Untethered from its original moorings, and now dwarfed by the encompassing voids, the old church that once towered above its urban setting lies marooned like a large reef in a vast square.

She has no affection for Haussmann, whom she introduces with John Russell’s cruel description: “heavy of eye and tread, stiff, coarse, demanding, humourless, and vain.” Following recent scholarship, she notes the emperor’s attempts to “mollify the working classes with public works” and ambitious ideas for public housing. “When it came to the proletariat,” she concedes, “Napoleon III was far more liberal” than Haussmann. But ultimately, she argues, he did little to soften the exploitative practices at the heart of the renewal projects: “The Second Empire’s urban strategies constituted class war by other means—urbanism, speculation, and expropriation, among them.” The book also indicts Napoleon’s regime for using urban renewal to promote colonialism, notably by flaunting France’s overseas possessions in the “exotic” artifacts and flora displayed in parks, gardens, and international expositions.

And yet, despite these stern verdicts, da Costa Meyer cannot disguise her fascination with what the Second Empire accomplished. While carefully explaining that the new water supply system benefited the wealthy central districts far more than the city’s poor periphery, she still praises the “daring technology and elegant simplicity” of the aqueducts designed by the engineer Eugène Belgrand: “With its taut arches and crisp detailing…Belgrand’s aqueduct makes a powerful impression as it sweeps across the landscape.” While insisting that new parks such as the Bois de Boulogne and the Bois de Vincennes benefited the elite more than the workers, her close descriptions and gorgeous color illustrations show just how much care went into their design and construction:

Streams tied different parts of the composition together, winding through the park like silver ribbons…. Sound, as much as form, was half the pleasure. White water was contrasted to still water, the roar of cascades to the quietude of ponds and marshes.

The considerable pleasures of the book derive above all from such unexpected, carefully observed details. Da Costa Meyer notes that when gas lighting first came to Paris, in 1817, it provoked considerable opposition:

Gas emitted a terrible stench, ruined trees and vegetation…and also met with strong hostility from the church, which condemned it as a simulacrum that reproduced God’s alternating cycles of light and darkness.

Yet by the end of the century, with the arrival of electric illumination, the older innovation had become an object of nostalgia, as in this passage from Robert Louis Stevenson: “In Paris…a new sort of urban star now shines out nightly, horrible, unearthly, obnoxious to the human eye; a lamp for a nightmare!… To look at it only once is to fall in love with gas.” Da Costa Meyer writes that even today the city has three hundred kilometers of underground space where urban quarries once operated: “One tenth of Paris is suspended above underlying voids.” And she provides a short, instructive design history of that unlamented urban amenity, the outdoor urinal.

She also has surprising things to say about the sewers. For one thing, the efficient new system did not meet with universal approval. Before its construction, entrepreneurs had hauled human waste to the suburb of Montfaucon and spread it out in giant pits to separate into liquid and solid. The former was processed into ammonium sulfate, the latter “cut into pieces to be sold as poudrette, a dry, odorless fertilizer much favored by local farmers.” The new sewers, even while improving the atmosphere of Paris, killed this source of profit. On the other hand, Haussmann managed to turn the new system into a showcase for the empire. Starting in 1867, guided tours were given in special trains and boats, directed by uniformed sewer men and accompanied by music and light shows. An American journalist commented, “apparently without irony,” that “the presence of lovely women can add a charm to the sewer.”

This rich material shows that, however tragic the consequences of Haussmannization for the Parisian lower classes, the process was ultimately far too complex and interesting to be squeezed under the stark, reductive term “class war.” Da Costa Meyer’s book offers a valuable reminder of the high price paid by most Parisians for the beautiful new city center, and a valuable rejoinder to the countless celebrations of Haussmann’s Paris as the “capital of the nineteenth century.”

But absorbing her lessons does not mean canceling our appreciation for what Haussmann and Napoleon III built. The Polish writer Tadeusz Borowski, after his liberation from Auschwitz, reflected:

Only now do I realize what price was paid for building the ancient civilizations. The Egyptian pyramids, the temples, and Greek statues—what a hideous crime they were! How much blood must have poured on to the Roman roads, the bulwarks, and the city walls.

The words ring true—but we don’t cease to marvel at the pyramids. We shouldn’t cease to marvel at Paris, either, however much we may deplore the processes that, more than any other, gave the city its present form.

The magic of great cities comes from the fact that even if their constant reinvention rarely proceeds from pure motives, it can never be reduced to impure motives. Whatever the plans of the bureaucrats and the building contractors, others—bohemians, immigrants, students, inventors, actors, artists—come along to impose new meanings and to put the city to new uses. Scarcely had the Second Empire vanished in 1870 than a new generation of painters—Caillebotte, Renoir, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Cassatt—were discovering new forms of beauty in the boulevards that had sliced so brutally through an older Paris. We continue to find new forms of beauty there today. Whatever its history, the city is what we make of it.

-

*

See François Loyer, Paris XIXe siècle: L’immeuble et la rue (Hazan, 1987); and David Van Zanten, Building Paris: Architectural Institutions and the Transformation of the French Capital, 1830–1870 (Cambridge University Press, 1994). ↩