When European commentators in the 1830s admired the brilliantly colored, life-size prints in John James Audubon’s The Birds of America, they found the backgrounds almost as enthralling as the birds: forest clearings, swamps and canebrakes and waving prairie grasses—an unknown country. The land, not the sea, was Audubon’s element. Whereas “the Land Bird flits from bush to bush, runs before you, and seldom extends its flight beyond the range of your vision,” he complained that “it is very different with the Water Bird, which sweeps afar over the wide ocean, hovers above the surges, or betakes itself for refuge to the inaccessible rocks on the shore.” Moreover, he disliked being on water. On ships he was seasick, bored, restless, longing to stride on solid ground with his gun. While becalmed in the Gulf of Mexico, he wrote, “My time goes on Dully Lying on the Deck on my Matress, on a hard pressed bale of Cotton, having no one scarcely to talk to, only a few Books.” (Aptly, these included Byron’s The Corsair.) Years later, approaching the Labrador coast through choppy seas, he wrote that “the cry of land soon made my heart bound with joy.”

Audubon at Sea, a selection of his oceangoing writings, asks us to imagine this landsman “challenged, on a deeply existential level, by an environment where he couldn’t rely on the instincts that normally made him such an effective observer and hunter of birds.” The focus is on Audubon as writer as much as artist, and the effect is strange and powerful. The texts are impeccably edited by Christoph Irmscher and Richard J. King. (King selected them, Irmscher wrote the eloquent introduction and headnotes, and they collaborated on the wide-ranging notes.) The book’s central section, framed by entries from a journal of a voyage to Britain in 1826 and an expedition to Labrador in 1833, contains extracts from the five-volume Ornithological Biography, which Audubon wrote to accompany the bound volumes of plates, feeling that the engravings alone could not convey America’s natural wealth and varied landscapes. Increasingly confident, he reused material from his journals, weaving his raw notes into smoother narratives with the help of his Edinburgh editor, William MacGillivray, who polished his prose, Irmscher tells us, “channeling the syntactic torrents Audubon had unleashed into shorter sentences” and amending his eccentric diction.

Despite Audubon’s lapses into flowery overwriting, the extracts in this volume make for captivating reading, sweeping us from the reefs of the Florida Keys up the Atlantic Seaboard to the icy rocks of the Canadian Maritimes. Everywhere we feel the pressure of his obsessive quest to record and draw every bird he could, and his journals in particular expose all the moody complexity of a man Irmscher describes as “passionate, outrageous, salty, vain, and brutal, despondent, vulnerable, sentimental, self-ironical, and tender.”

A charismatic figure with long hair, a piercing gaze, and a loping stride, Audubon was attacked during his lifetime for errors and plagiarism, for failing to acknowledge engravers and collaborators, even for inventing birds like “Cuvier’s Kinglet,” which he described as a small wren, naming it after the French naturalist Georges Cuvier, or the patriotically named “Bird of Washington,” Falco washingtonii, which he claimed was an unknown species of sea eagle. (It could have been a juvenile bald eagle.) Several of the species he painted remain mysterious, but rather than inventing them, Audubon may simply have made mistakes or confused species, relying on faulty memory or working with damaged skins.

Partly through a deep-seated fear of being exposed as illegitimate, a damaging slur in this period, he also adjusted the facts of his life to suit his needs, from identifying as an “American Woodsman” to claiming that he was born in Louisiana, that his mother was a highborn Spanish woman who died in the Haitian Revolution of the 1790s, and that he had studied in Paris under Jacques-Louis David. In fact, he was born in 1785 in Saint-Domingue (Haiti), the son of a trader from Nantes, in western France, who had become a plantation owner. His mother, Jeanne Rabin, a French maidservant, died about six months after his birth. During the Haitian uprising, Audubon (like his younger sister Rose, the daughter of another, mixed-race servant) was sent to Nantes. Here he stayed, apart from a brief, unsuccessful spell as a naval cadet, until 1803, when his father, who also owned property near Philadelphia, packed him off to the US to avoid conscription in the Napoleonic Wars.

Audubon’s American life included an unquestioning acceptance of slavery, and since the publication of a powerful article, “What Do We Do About John James Audubon?” by the Black ornithologist J. Drew Lanham in the magazine of the National Audubon Society in the spring of 2021, his already tarnished reputation has been battered anew. As well as being a slaveowner’s son, he owned slaves himself when he ran a store in Henderson, Kentucky, from 1811 to 1819, and again in the 1820s. Acknowledging this, in both the introduction and a coda to their book, Irmscher and King note how the transatlantic passage that brought his father’s slaves to Saint-Domingue was “the end of freedom; for many of them, it also meant death,” while for Audubon, “ocean travel meant liberation,” whisking him from revolutionary turmoil in Haiti and France and carrying him to Britain and the start of his fame in 1826.

Advertisement

While Audubon did not so much as blink at slavery, his attitude toward indigenous peoples, though equally racist, was more conflicted. Writing of a Seminole hunter in Florida, he laments, “Alas! thou fallen one, descendant of an ancient line of freeborn hunters, would that I could restore to thee thy birthright, thy natural independence…. But the irrevocable deed is done.” During an evening with British naval officers in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, he recalled:

Some one said, it is rum which is destroying the poor Indians. I replied, I think not, they are disappearing here from insufficiency of food and physical comforts, and the loss of all hope, as he loses sight of all that was abundant before the white man came, intruded on his land, and his herds of wild animals, and deprived him of the furs with which he clothed himself. Nature herself is perishing.

He met and admired people from many tribes, but although their fate moved him, he saw them almost as another species, doomed to extinction in a struggle for survival.

In the mid-1820s Audubon became determined to publish life-size engravings of all the birds of America, keen to outdo the Scots poet and naturalist Alexander Wilson, whose American Ornithology had appeared between 1808 and 1814. Hearing that he could find engravers equal to the task only in England or France, in April 1826 he sailed to Liverpool, leaving his wife, Lucy, and their two teenage sons in Louisiana. His journal of the voyage was in part a long letter to Lucy. Giving no thought to style, he let his English grammar slip and his images run wild, while his French accent sounds in spellings like “anstant” instead of “instant.” As Irmscher points out, these helter-skelter notes place us by his side: “We even feel the dampness of the paper as we turn the page. And, most importantly, we hear his voice.”

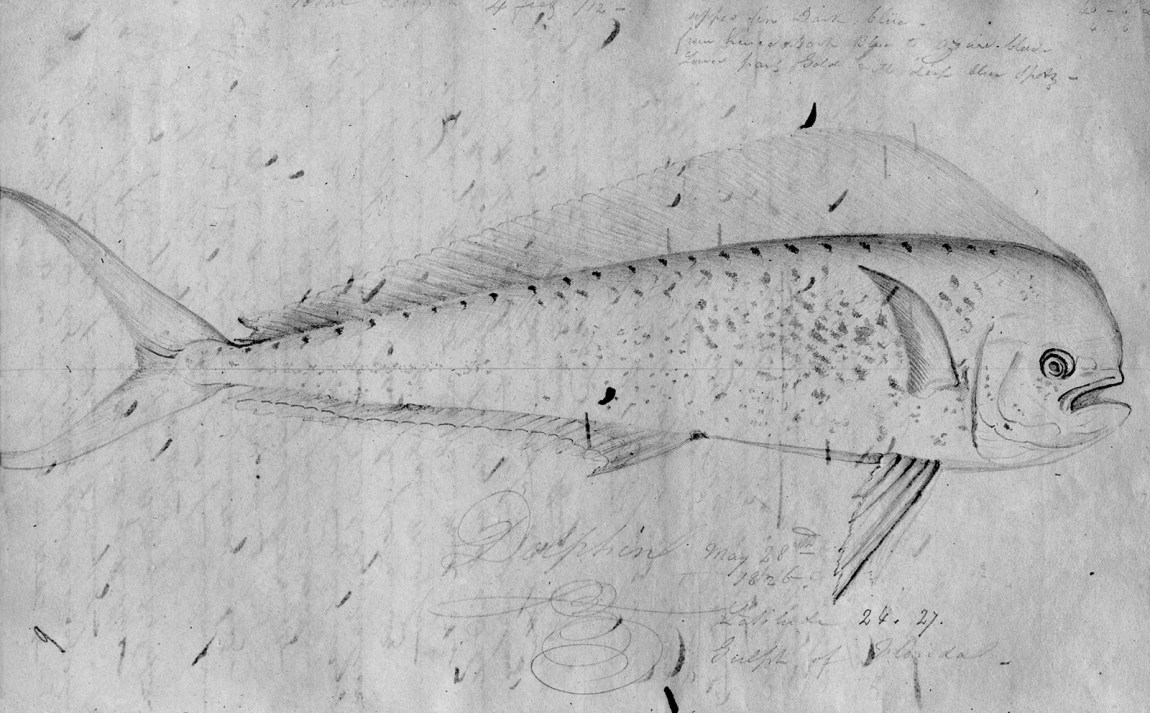

That voice rings with excitement. He watches a “Dolphin” (identified today as the mahi-mahi, dorado, or dolphinfish, Coryphaena hippurus) catching flying fish as it bounces high in the air “and so rapidly moves toward his pray that oftentimes the little fish just falls to be swallowed by his antagonist.” A “Porpoise” (probably a bottle-nosed dolphin) hooked roughly onto the deck “gave a deep groan, much alike the last from a large dying Hog.” Having never seen one before, Audubon pored over “new matters of observation—their large Black, sleek body, the Imensity of warm black blood issuing from the Wound, the Blowing apperture placed over the forehead.” The next morning, when he opened its stomach, the intestines were still warm.

He drew scenes of shipboard life, dissected fish and birds, recorded the fate of the cook’s hen that “imprudently” flew overboard, and sighed as the little alligator he had brought died, “through My want of Knowledge that Salt watter was poisonous to him.” Above all he watched the birds, especially the flocks of petrels—“Mother Carey’s Chickens”—“raising & falling with such beautifull ease to motions of the Waves that one might Suppose they receive a Special power to that Effect from the Element below them.”

In Britain he won important allies and subscribers, gradually adding others in Europe and America who financed his expensive publication over the years. In Edinburgh he also found his first engraver, William Lizars, soon replaced by the more skilled Robert Havell and his team of colorists. Havell began engraving The Birds of America in 1827, printing the 435th and final plate in June 1838. Quite soon after starting, however, Audubon became aware of the lack of waterbirds: the first of these, the dramatic “Fish Hawk, or Osprey,” did not appear until plate 81. To remedy this, in late 1831 he sailed along the east coast of Florida and the following spring joined a government revenue cutter sailing down the curving line of the Florida Keys. His Labrador expedition followed two years later.

The Ornithological Biography incorporated “bird biographies” written on a set model, opening with a description of habitat and a dynamic account of how Audubon saw and obtained the bird, and then discussing migration, flight patterns, courtship rituals, nests and eggs, and the rearing of young. The descriptions are both vivid and precise. We learn, for example, that the female Wilson’s plover lays her eggs around June 1, twenty or thirty yards from the high-tide mark,

Advertisement

scratching a small cavity in the shelly sand, in which she deposits four eggs, placing them carefully with the broad end outermost. The eggs, which measure an inch and a quarter by seven and a half eighths, are of a dull cream colour, sparingly sprinkled all over with dots of pale purple and spots of dark brown.

This technical approach was enhanced by a final appendix including anatomical drawings—“an endless gallery of death,” Irmscher calls it—composed by Audubon’s Scottish editor, MacGillivray, and complete with drawings “of lungs, tracheae, and looping intestinal tracts.”

Audubon liked to see himself as a scientist and was admired as one by Charles Darwin, for instance, who quoted him more often than any other British or American naturalist. Yet the “biographies” are far from objective, making a deliberate play for the reader’s sympathy through repeated parallels with human experience and emotions. The frigate pelicans, greedily pouncing on their prey, become archetypal villains, “lazy, tyrannical, and rapacious, domineering over birds weaker than themselves, and devouring the young of every species, whenever an opportunity offers.” The sooty terns exchange “curious reciprocal nods of their heads, which were doubtless intended as marks of affection.” The young razor-billed auks “were very friendly towards each other, differing greatly in this respect from the young Puffins, which were continually quarrelling.” “Look at the birds before you,” he commands us, pointing to the common cormorant,

and mark the affectionate glance of the mother, as she stands beside her beloved younglings!… The kind mother gently caresses each alternately with her bill; the little ones draw nearer to her, and, as if anxious to evince their gratitude, rub their heads against hers.

Audubon’s stance is that of a showman, opening his arms wide on a stage, his exhortations, anthropomorphism, and use of the present tense drawing the audience in. “Reader,” he writes,

imagine yourself standing motionless on some of the sandy shores between South Carolina and the extremity of Florida, waiting with impatience for the return of day;—or, if you dislike the idea, imagine me there.

In Labrador, “stay on the deck of the Ripley by my side this clear and cold morning,” he begs, the calm heightening the coming terror of an unexpected storm. His passionate engagement leaps off the page.

Storms do not slow the seabirds. Audubon recreates, as far as he can, their wild, strange cries. He is in awe at their mastery of the air, at the way they fly far out to sea and dive into the rolling waves to make their catch, and their great numbers never fail to astonish him. Air and sea were full of birds. When he reached the sandstone towers of Great Gannet Rock (now known as Bird Rock), soaring from the waves off Cape St. Mary’s, Newfoundland,

the air for a hundred yards above, and for a long distance around, was filled with gannets on the wing, which from our position made the air look as if it was filled with falling snowflakes, and caused a thick, foggy-like atmosphere all around the rock.

Off Labrador, “the air along the shore was filled with millions of velvet ducks and other aquatic birds, flying in long files a few yards above the water.”

Amazed delight, however, is always accompanied by violence. In Irmscher’s words, “As an artist, he sought to preserve birds for eternity; as a naturalist, he hunted them, killed them (by the barrelful), and often ate them, too.” Landing at Indian Key in April 1832, Audubon remembered, “My heart swelled with uncontrollable delight.” The birds of Florida were almost all new to him, “arrayed in more brilliant apparel than I had ever seen before,” but within hours the guns were out. Finding a large flock of pelicans, he and his companions took aim:

A discharge of artillery seldom produced more effect;—the dead, the dying, and the wounded, fell from the trees upon the water, while those unscathed flew screaming through the air in terror and dismay. “There,” said [the pilot], “did not I tell you so; is it not rare sport?”

I felt glad when the birds struck back, biting his hand or ascending in protest, as sooty terns did when faced with a large landing party:

All those not engaged in incubation would immediately rise in the air and scream aloud; those on the ground would then join them as quickly as they could, and the whole forming a vast mass, with a broad extended front, would as it were charge us, pass over for fifty yards or so, then suddenly wheel round, and again renew their attack.

When the sailors shouted,

the phalanx would for an instant become perfectly silent, as if to gather but meaning; but the next moment, like a huge wave breaking on the beach, it would rush forward with deafening noise.

The martial imagery suggests that Audubon recognized his quest as a war on nature, an assault that inevitably undercuts his status as a founding father of conservation. Yet the plates soar free: the brown pelican tucking its long beak into its curved neck, one eye glinting sideways; the black skimmer diving into the waves, its wings flaring behind (see illustration on page 50); the fearsome “Fish Hawk, or Osprey” carrying its prey; the tender “father and son” portrait of gannets amid choppy seas, the adult’s white plumage forming a backdrop for his speckled young.

The birds are not the only beings to fill these pages. The Ornithological Biography also included short narratives—“delineations of American scenery and manners,” he called them—as entertainments particularly for European readers. Several are included here, clarified by meticulous notes by King and Irmscher on individuals and ships, occupations and trades, that run alongside the texts almost as a parallel book—an entire survey of coastal life.

The men Audubon meets, though (and they are nearly always men), are all predators, from the “turtlers” of the Dry Tortugas, who heave hefty leatherback turtles over their shoulders to get at their eggs, to the wreckers of the Florida reefs. The mood is darker in Audubon’s account of Labrador, matched by the weather, which is “shocking, rainy, foggy, dark and cold.” He was feeling his age. In May 1833 he was slowly recovering from a stroke when he cruised into the Bay of Fundy, between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, rich in seals and porpoises, ravens and eagles, guillemots and eider ducks, but a threatening place of cliffs, gales, and tides that he was glad to escape. A month later, taking five younger men, including his son John, he chartered a schooner, the Ripley, and sailed past Cape Breton Island, off the Nova Scotia Peninsula, to the Magdalene Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the mossy, mosquito-ridden shores of Labrador.

As Irmscher says, Audubon, like Melville, “leads us across the water to the edge of things, to the place where life and death meet.” In these icy northern waters he sees the cod fishers of Eastport, Maine, sending three hundred boats to the banks every day, and “when Saturday night comes about 600,000 fishes have been brought to the harbour.” Near the estuary of Bras d’Or on Cape Breton Island, great chunks of whale blubber lie on the shore, ready to be boiled. In the harbor, 1,500 seal carcasses stripped of their skins are piled high, with dogs tearing at the flesh and the stench filling the air. On the Labrador coast, drunken eggers ravage whole colonies of nesting murres, plundering the nests for eggs to sell in the markets, crushing the shells that hold chicks to force the birds to lay more.

To escape this depredation, some species had already moved farther north. Indeed, everywhere Audubon looked, he saw that seabirds were disappearing. Puffins still bred in the Bay of Fundy, “although not one perhaps now for a hundred that bred there twenty years ago.” Some birds, like the great auk, seemed to have gone already, although Havell’s brother had “hooked” one a few years earlier off Newfoundland. Audubon had to draw his great auks from a stuffed specimen, Irmscher writes: “Frozen in timelessness, great auks were, for all he knew, gone from nature; even in Audubon’s fertile artistic imagination, they are little more than monuments to their own demise.” Killed for their meat and their down and pinfeathers, they would be extinct within a few years.

The introduction to Audubon at Sea opens with an evocation of the last pair of auks on the island of Eldey, off Iceland. After each extract from Audubon’s writing, like small hammer blows, note after note identifies every bird with its current name and gives its place on the international Red List of Threatened Species. Seabirds, “adapted to a marine environment…for sixty million years,” are disappearing. Their nearly 350 species, the editors remind us, are a crucial indicator of ocean health, but a 2015 study showed a decline over sixty years of 69.7 percent of monitored populations. Audubon’s plates and writings remind us “of what it is that we need to save, if we want to save ourselves.” They remind us, too, that like Audubon, we are all complicit in this devastation.