“The Clamor of Ornament” is a summer spree of a show. It intrigues. It delights. At times it thrills. But it doesn’t ever add up. And in the end it falls apart. The curators in charge—Emily King, Margaret-Anne Logan, and Duncan Tomlin—beguile with nearly 150 works. They include sixteenth-century woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer after designs by Leonardo da Vinci, nineteenth-century Japanese woodblock prints, studies of the stone inlays in the Taj Mahal, drawings by the American architect Louis Sullivan, Native American weavings, and a piece of scrimshaw engraved with a scene of a disaster at sea. The invigorating excess is abetted by a suave exhibition design by the London firm Studio Frith, with some walls painted in primary colors and others covered with retro-chic wallpaper in classical and Gothic designs. There’s real fun to be had here. Would that the curators had left it at that. The show’s subtitle, “Exchange, Power, and Joy from the Fifteenth Century to the Present,” puts us on notice that things are not so simple. The catalog essays feature ideological arm-twisting and theoretical mind games that leave me wondering whether the people involved regard their joy as a sin demanding expiation.

The exhibition’s theme, a great one, is the universal desire to animate surfaces—anything from a sheet of paper to a stretch of wall to a person’s arm—with visual rhythms, patterns, and designs. The Drawing Center, a relatively small but scrappy institution that has inspired an ardent following since the pioneering days of New York City’s SoHo in the 1970s, doesn’t have the resources to entirely encompass such an enormous subject. But it has an appealing reputation for playing David to the Goliaths among New York’s museums. The plentiful though often modest works on display suggest the astonishing variety that the ornamental impulse has inspired across centuries and continents.

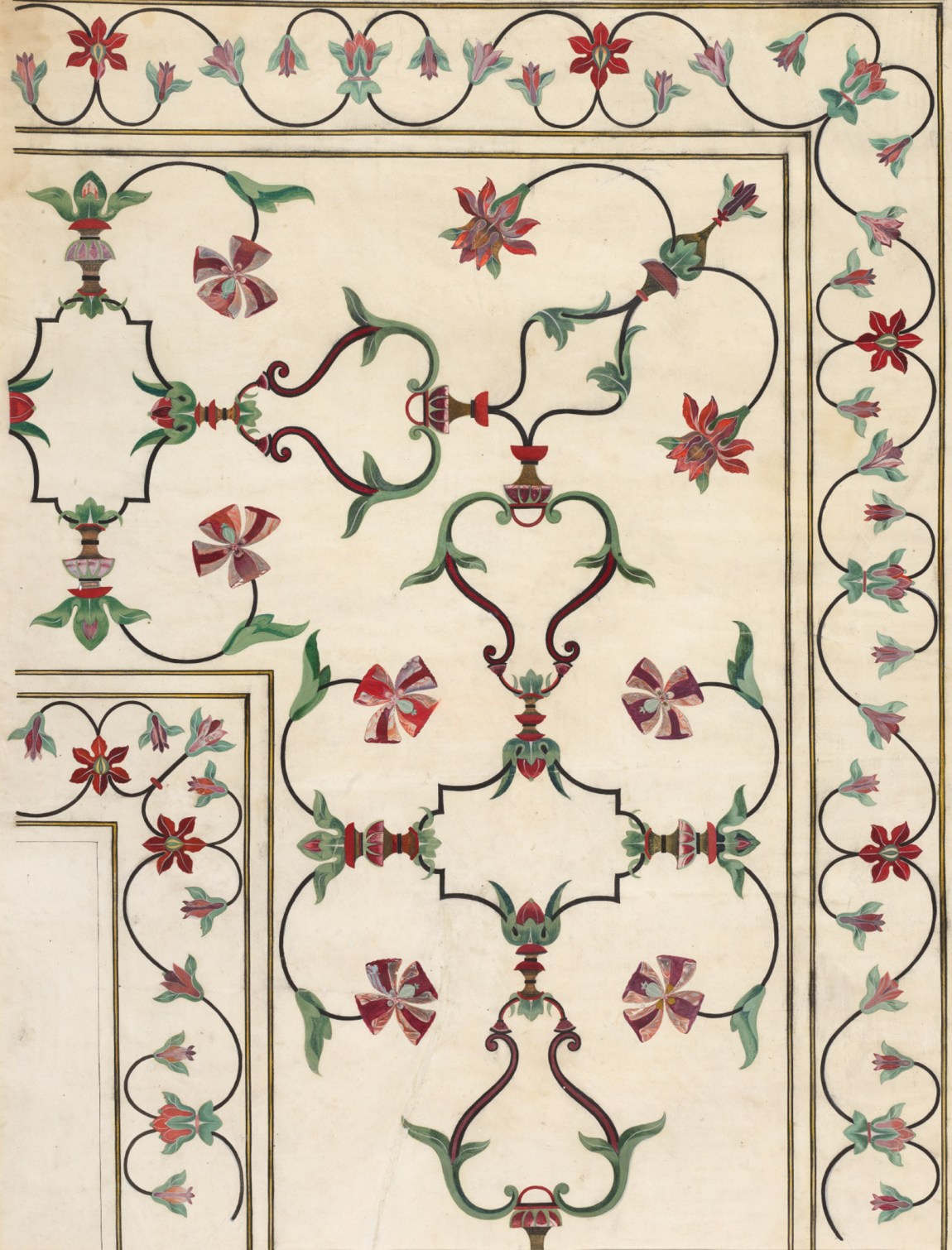

Near the beginning of “The Clamor of Ornament,” a gathering of eighteenth-century works, including an etching after a bucolic fantasy by Watteau and several drawings for a mantelpiece and a chimney by Piranesi, have a dreamlike, filigreed intricacy. Here ornament feels introspective, speculative, almost philosophical. Elsewhere ornament is closer to a bold assertion, a devouring of space. I felt that in the work of nineteenth-century English designers, among them William Morris, William De Morgan, and Christopher Dresser. An even more muscular rhetoric gives two painted tapa panels, from Papua New Guinea and Oceania, an immediacy, a pragmatism. While symmetry and repetition are almost inevitably organizing principles in many of the works on display, juxtaposition turns out to be another powerful principle. One of the most striking objects, a nineteenth-century Mexican sampler, confounds whatever orderly rectilinear divisions the anonymous artist has imposed with a giddy explosion of differently stitched areas in a rainbow of cotton and silk threads. This is a homespun psychedelic vision.

“The Clamor of Ornament” presents a winningly, maybe even bewilderingly capacious definition of “ornament.” I was interested to see among the works on view the engraved title pages of two pieces of nineteenth-century sheet music, which are essentially exercises in typographical arrangement, albeit accompanied by ornamental curves, curlicues, and flourishes. Here ornament is an add-on, inarguably charming. When you turn from this to the gorgeously adumbrated architectural forms of Cairo’s Mosque of Sultan al-Hakim, as seen in a spectacular daguerreotype by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey, you’re confronted by ornament not as something charming but as something sublime. The artists and architects who conceived and constructed the monuments of the Islamic world gave ornament a privileged place at the center of social, religious, and political life. “The Clamor of Ornament” is militantly international. That’s all to the good.

The curators encourage us to complicate any generalizations we’re tempted to make. They have embraced so many different media, moods, modes, and points of reference that the best way for a museumgoer to take in the exhibition is probably as some version of a Baudelairean flaneur, the connoisseur of modern experience who is always looking here and there, absorbing this and that, without knowing or maybe even caring what it all means. Some visitors, happily aware that there’s a flaneur’s funhouse—the visual onslaught of SoHo—just beyond the doors of the Drawing Center, will be primed to experience the show as one more twist in the contemporary spectacle. When, toward the end of “The Clamor of Ornament,” I found myself in front of two leather handbags with elaborate metal handles, designed in 2018 by Bethan Laura Wood for Valextra, I felt I might as well be in one of SoHo’s pricier shops.

What are the curators telling us by including Wood’s handbags, which hardly strike me as high points in the history of ornament or design? Are they suggesting that wandering through an art exhibition and wandering through a high-end shopping district (or for that matter any shopping district) are more or less the same thing? Are all visual experiences and desires equal or potentially equal? These are interesting questions. Philosophers have long argued about the relationship between aesthetic experience and other experiences. But instead of attempting to grapple with these questions, the curators seem determined to keep changing the subject. They’re acting less as curators than as flaneurs. The range of the show, from a fifteenth-century German engraving to a 1981 photograph by Henry Chalfant of a New York City subway car covered with graffiti, goes down easily amid the subdued elegance of the Drawing Center. Elegance can be a cop-out.

Advertisement

Initially, I took the exhibition’s teasing title as a lighthearted allusion to Owen Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament, a book first published in 1856. But it turns out to have a crude polemical purpose. You only have to read a few sentences into the first of King’s catalog essays to realize that she’s setting up Jones as a fall guy, because, she writes, he wanted “to establish a set of universal rules, strictures that would apply to ornament in every instance, no matter its inspiration or application.”

Jones, according to King, was “one among several mid-nineteenth-century ornament authoritarians.” She may want us to glide over this remark as if it were merely clever, a rhetorical wink. Later in her essay she admits that she and her colleagues “are with Jones in delighting in ornament.” But as far as I’m concerned, King has put herself beyond the reach of rational discourse by suggesting that Jones, because he aimed to define some general principle or principles, was an authoritarian thinker. She believes that his work “reflects an imperialist point of view.” An introductory wall text at the Drawing Center informs visitors that his thinking was shaped by “the colonialist’s desire to make rules.” To dismiss as authoritarian, much less imperialist or colonialist, a writer who wants to understand the universal appetite for ornament amounts to blackballing the search for beauty. The people involved with this show don’t seem to understand that the pluralism that they’re right to celebrate becomes meaningless when divorced from some broader, universal vision. Without even the promise or hope of univeralism, what you end up with is a hectoring, nihilistic pluralism.

“In swapping ‘Grammar’ for ‘Clamor,’” King writes, “we are amplifying ornament’s propensity to communicate.” The only reasonable response to this ridiculous assertion is to ask how there can be any communication, at least any worthwhile communication, without a common grammar. It would seem that anything that suggests an effort to establish what King refers to as “overarching principles” is suspect. You can of course take issue with one or another of the propositions that Jones offers in the book he published some 150 years ago. You might quite plausibly dispute his declaration, near the outset, that “all ornament should be based upon a geometrical construction.” What disturbs me is King’s rejection of Jones’s encyclopedic ambitions. Fundamentals don’t interest her. She refers to Jones’s belief “that the desire for ornament was elemental to human nature” as “an Adam-and-Eve way of seeing things.” King is twitting the eminent Victorian. At one point she compares Jones’s thought to Darwin’s theory of evolution. Does she also regard Darwin’s ideas as annoyingly authoritarian? Her somewhat joking tone leaves Jones’s ambitions looking not so much wrongheaded as pompous, absurd. This is mockery, not debate. The winning informality of “The Clamor of Ornament” can’t entirely disguise an underlying skepticism—a self-mockery, a sense that nothing that’s on display is such a big deal.

There isn’t an idea that has circulated in artistic and academic circles in the past fifty years—from the liberating power of camp and kitsch to the symbiotic relationship between art and money to the political nature of all artistic expression—that King and her colleagues don’t take up casually, as if ideas were whims, partners to try out for a dance or two and then dismiss. She announces that “the story behind beauty encompasses violence and trauma,” as if the relationship between violence, trauma, and beauty were so perfectly obvious that nothing more need be said. The catalog features an essay by the Scottish writer Shola von Reinhold, a defense of “the ornamentality that occupies me and which I adore,” which amounts to a sketch for a been-there-done-that version of radical chic. Susan Sontag’s “On Style,” from her first essay collection, Against Interpretation, is invoked before being quickly dismissed. Von Reinhold finds fault with Sontag’s “lumpy and heterogeneous” vision of “stylization,” which betrays a “measuredness” that apparently had everything to do with maintaining “her own intellectual standing.”

Advertisement

King begins her second catalog essay by alluding to “Ornament and Crime,” the famous critique of ornament by the early-twentieth-century architect Adolf Loos, after which she gets into a wrangle with the forever fashionable Roland Barthes about what some apparently see as his misunderstanding of fashion. A few pages later she salutes Dapper Dan, the Harlem tailor and designer who got into trouble with some high-end labels by “reimagining” their logos. After that there’s a nod to what she refers to as “another significant outlet for ornament in 1980s New York,” graffiti, and she praises “the vast and complex compositions that were executed on the city’s subway cars.”

The attitude of these essays is weirdly off the cuff. Assertions are made for assertion’s sake, with nobody bothering to back anything up. King announces that “trade in ornamented textiles played a role in the enslavement of African people.” While she goes on to admit that “not all of those cottons were ornamented,” I’m left wondering if her point is that the ornamentation of the textiles had a particular role to play. If the textiles had been unornamented, would the story be different? The political thought feels knee-jerk, sclerotic. The references to Sontag, Barthes, and graffiti art recap old enthusiasms and controversies so perfunctorily that the writing turns rancid.

“We are not here to judge or censor,” King explains, apparently speaking not only for herself but for her co-curators. This is nonsense, as she lets on earlier in the very same sentence, when she admits that “the act of curating necessarily involves a process of selection.” King is proposing a new, let-the-chips-fall-as-they-may kind of curatorial activity: selection without judgment. Some of the selections, especially among more recent work, are so predictable as to feel arbitrary. That’s my reaction to the posters designed in the 1990s by John Maeda. We know why they’re here—Maeda is a design guru, a major figure in computer graphics—but these compositions amount to nothing more than a recapitulation of the strategies of Op Art, which was the next new thing in the 1960s and is experiencing something of a revival today.

I find it telling that King mentions censorship, if only to argue that she and her colleagues aren’t censors. Whatever the semantics involved in defining censorship, there’s no question that the curators have some very definite ideas about what is and isn’t admissible. While a show as heterogeneous as this one discourages museumgoers from discerning underlying patterns, anybody with more than a passing interest in the history of ornament can see that the curators have pretty much ignored the leading artists, architects, and designers of the past 125 years and their engagement with the entire question of the nature of ornament. There is one work by Paul Klee, but the exhibition includes nothing by the architects Frank Lloyd Wright and Antoni Gaudí; the artists Sonia Delaunay, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Anni Albers, and Henri Matisse; or the graphic designers Willem Sandberg and Paul Rand. What all these creative spirits (I could mention others) had in common was a fascination with precisely the grammar of ornament that King has rejected in the thought of Owen Jones, whose ideas are part of the prehistory of modernism.

Everybody involved with “The Clamor of Ornament” is in revolt against a line of thinking that von Reinhold dismisses as “Kantian harmony.” They do not believe that a vigorous appreciation for the variety of visual expressions in different times and places must be grounded in some sense of the ultimate unity of art. They will say that unity has all too often been used to justify a stultifying academicism. There are times when that is true. But the hunger for unity can also confound prejudice and small-mindedness. That’s what made it possible for the neoclassical sculptor John Flaxman, in the lectures he gave at the Royal Academy in London in the early nineteenth century, to see in the utilitarian objects of people he referred to as “savages” an “elegance of form” and an aptness in “additional decoration in relief on the surface of the instrument, a wave line, a zig-zag, or the tie of a band.”

King will of course want to call out Flaxman—as she calls out Jones—for the use of the word “savage.” But a feeling for the grammatical power of ornament enabled these men to see elegance and authority even in the work of people they regarded as primitive. Modernism built on that sense of a pluralism grounded in universalism, from the artists who edited The Blue Rider Almanac (1912) and included non-Western art along with their own work, to Herbert Read’s Art and Industry (1934), a book that reveals affinities between preindustrial and industrial objects, to the series of daringly eclectic exhibitions organized by the adventuresome curator Jermayne MacAgy in San Francisco and Houston from the 1940s to the 1960s.

There is a wonderful passage about the unity of the ornamental impulse in the memoirs of the mid-twentieth-century New York gallery director John Bernard Myers, Tracking the Marvelous: A Life in the New York Art World (1983). Myers recalls that in the early days of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, where he exhibited artists including Helen Frankenthaler and Larry Rivers, he mounted a show of antique lace from the collection of a Mrs. Grey. Among its most enthusiastic visitors was Jackson Pollock, who

came twice and took great pleasure in the notion of art anonyme; the rhythms of swirl and crosshatch, even the highly conventionalized images of French eighteenth-century lace, with its peacocks, pheasants, roses, waterfalls, grottoes, pagodas, ruins and costumed personages, delighted him.

Myers hardly needs to explain that for Pollock the rhythms and convolutions of these ornamental achievements had some kinship with his own paintings, with their dripped painterly arabesques. As for Mrs. Grey, the lace collector, she wasn’t surprised by Pollock’s response, for she was an admirer of his “lovely skein pictures.” What Pollock and the anonymous lace makers shared was a language.

The irony of “The Clamor of Ornament” is that, however the curators may recoil from the possibility of an integrated visual language, when it comes to actually hanging a show, formal affinities prove irresistible. The best parts of the exhibition feature groupings by color, rhythm, shape, scale, and various other basic organizing principles. While in the catalog, as if to demonstrate once and for all the cacophony of ornament, the discussion of the hyperrefined decorations of the Taj Mahal runs right into a discussion of subway graffiti, in the exhibition these works are somewhat removed from each other. Only in the tangled imaginings of curators determined to reject both modernism and postmodernism in favor of “ornamentality,” whatever that might be, could India’s Taj Mahal and New York City’s defaced subway cars inhabit the same realm of discourse.

Confronted with the imperatives of visual experience, the curators can’t help but bring together works that actually speak to one another. One wall in the show is predominantly a celebration of floral motifs, with smaller objects framed by two larger inventions, an eighteenth-century Indian painted and resist-dyed cotton panel and an early twentieth-century quilt from the American Folk Art Museum, a pair of works in which nature’s bilateral symmetry inspires the dissonant rhythms of a decorative symmetry. As for the graffiti artists, they have their own small grouping toward the end of the show, including work by Andrew (Zephyr) Witten and Percel (Kies TNR) Shewatjon. I question their inclusion. They have rejected—or maybe never considered—the rhythmic consistency that is the essence of ornament. But I will be accused of being an ornament authoritarian.

“The Clamor of Ornament” is in many respects a modest show. I can already hear someone complaining that I’ve made too much of an exhibition that King, in her opening essay, declares “has no disciplinary agenda.” Everybody, we are given to understand, is doing their own thing. But there is something disturbing about the refusal to confront formal matters, as if recognizing ornament’s fundamental identifying characteristics poses a threat to modern identity politics.

In one of the most brilliant recent studies of the subject, The Mediation of Ornament (1992), the art historian Oleg Grabar argues that ornament is visual beauty detached from fixed meaning, significance, or signification. From this he deduces that ornament “alone among the forms of art is primarily, if not uniquely, endowed with the property of carrying beauty and of providing pleasure.” He goes on to conclude that an aesthetic experience freed of fixed meanings “gives to the observer the right and the freedom to choose meanings.” Grabar’s work, which isn’t mentioned in the catalog of this show, suggests some deep characteristics of ornament uniting the explosion of meanings that the organizers want to celebrate. But his arguments may strike King and her collaborators as questionable, because they are grounded in a painstaking analysis of a visual grammar.

At the Drawing Center we’re invited to consider ornament’s multiplying meanings. That’s the pleasure of this miscellany of a show. But it’s a miscellany that never asks us to even attempt to fill in the blanks or see the whole picture. It’s a miscellany dedicated to the proposition that all experience is in some sense miscellaneous. No wonder “The Clamor of Ornament” gives off some strange vibes. Behind the clamor there is chaos.