In September 1963 my family moved from Clarion, Iowa, to Osage, Iowa, eighty-two miles away. I was eleven, the oldest of four children. Both towns were roughly the same size—population three thousand or thereabouts—and their residential streets ended abruptly in cornfields. In Clarion, I knew everyone and everything. My friends were Bill and Greg and Scott, and I liked a girl named Jolene. In Osage, I knew no one and nothing. All the girls already had boyfriends named Chuck and Deke. And because we arrived after the school year had started, I suddenly found myself in a sixth-grade classroom full of strangers studying subjects from an alternate reality. Then the president was shot. Not quite three years later—summer 1966—my family moved once more, from Iowa to a suburb of Sacramento, California. I was fourteen and about to begin high school. It was less a move than a transubstantiation.

There’s another way to tell the story of those years. We moved to Osage just as the Beach Boys released their third album, Surfer Girl—the first to acknowledge Brian Wilson’s role as producer on the back cover. The Beatles’ earliest American hit, “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” erupted in late December. Soon after we got to Sacramento, Revolver appeared, and a few weeks later the Beatles stopped touring for good. Then came “Good Vibrations,” the Beach Boys’ last major hit and the beginning of the end of their important recordings.1 I’ve often wondered who I would have been if my family hadn’t moved to California when we did. But who would I have been without the Beach Boys and the Beatles from ages eleven to fourteen?

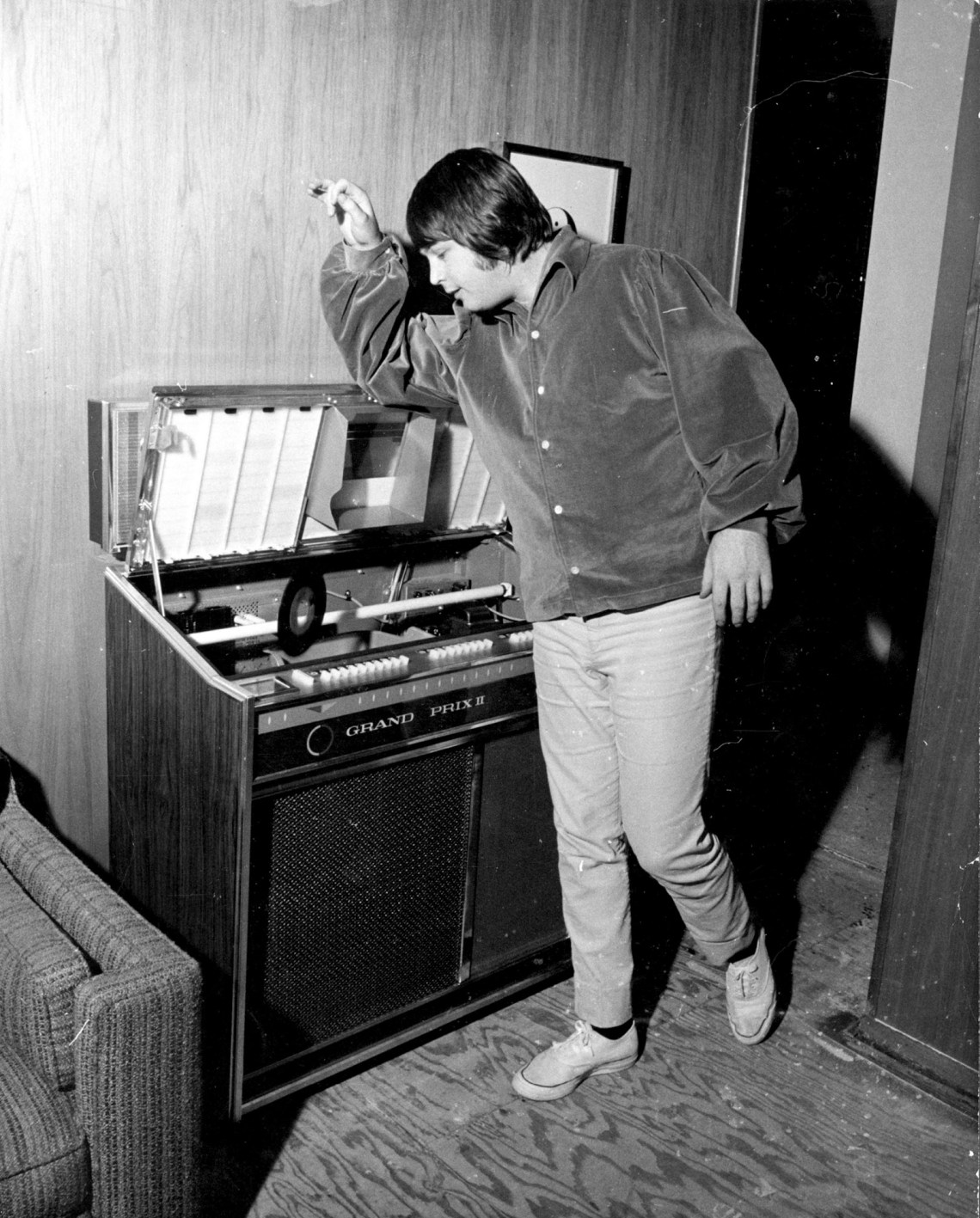

This was all long ago, and it’s tempting to talk about what was missing then—the digital and informational ubiquity we take for granted now, everything everywhere, all at once. But none of that was actually missing because it hadn’t been thought of. When I walked down Main Street to the one store in Osage with a (tiny) record section and paid ninety-nine cents for a 45-rpm single (“Fun, Fun, Fun” or “Ticket to Ride,” for example) and brought it home and put it on the record player, I was the first person who’d ever heard that very disc. I wasn’t siphoning the song from a ceaseless, invisible digital flood. I experienced a discrete event contained in the moment of listening, a personally owned artifact of black vinyl spinning on a platter while a needle wobbled in its grooves. How the wobbling turned into sound, how the record was written and recorded and produced and mixed and pressed and distributed, how the physical disc in its paper sleeve made its way to our little Iowa town to be traded for my allowance, and who made money from my allowance and in what proportions, I had no idea. Only the music mattered—and what it made me feel.

Because I had no older brothers or sisters, I’d heard almost no popular teen music by the time I was eleven—no Elvis Presley, no Buddy Holly, no Chuck Berry—so the Beach Boys and the Beatles hit me especially hard. Until then, music had been something that sifted vaguely down from the adult world above. (In Clarion, my favorite song was “Moon River,” sung by Andy Williams, who was a big deal in 1962.) And because I had no close friends in Osage, there was no one to share this new music with. Which was fine. Songs like “Don’t Worry Baby” and “She’s a Woman” were far too entrancing, in their different ways, to listen to in anyone else’s presence. I’d never kissed a girl or driven a deuce coupe or caught a wave or seen an ocean or a surfboard, but still the music spoke. A “woman” to me was a teacher or parent, possibly a school nurse, an inhabitant of the alien grown-up world. “Baby” was something a woman might have, not an endearment a girl might use when her boyfriend pushed the other guys too far. It was fascinating, every bit of it.

Strangely perhaps, I had no desire to see the Beatles or the Beach Boys perform in person. I owned the records and that was more than enough. When I saw A Hard Day’s Night in Osage in August 1964, it was instantly clear that the world of the Beatles was magically impenetrable in a way that could never be fully revealed in live performance or understood by being a member of a screaming audience. And when I bought the Beach Boys Concert album two months later, I realized that the touring Beach Boys were essentially a cover band, which has been true ever since.2 Every forthcoming revelation in their music would be found in the songs that Brian Wilson fashioned in the recording studio, not in their—or his—performances onstage.

Advertisement

Here I am nearly sixty years later, and it all still matters, as I can tell from my reaction to two recent documentaries. The first is Peter Jackson’s The Beatles: Get Back, which began streaming on Disney+ last fall and uses extensive footage shot in January 1969 by Michael Lindsay-Hogg. It’s simply the most interesting television I’ve ever seen, and it profoundly deepened my understanding of who the Beatles were and how they worked and why they ended. The second is Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road, directed by Brent Wilson (no relation), which was shown last year at the Tribeca Film Festival and is now part of the American Masters series on PBS.

The two documentaries could hardly be more different. There’s no interpretive overlay, no narration, no voiceover in Get Back because, in a sense, nothing needs explaining. No one needs to wonder aloud why this music still matters because it so evidently does—and because we get to watch it beginning to matter, song by song, as the Beatles rehearse. There’s nothing equivalent in the Beach Boys’ past—only concert footage and brief bits of film shot in the studio, circa 1966. (The Beach Boys were never remotely as visual as the Beatles.) To understand where their songs came from would require looking into the mind of Brian Wilson, a mind that has always needed a lot of explaining.

For five, maybe six years—1962 to 1967—the best songs Wilson wrote and recorded with the Beach Boys changed what was possible in popular music. But not afterward. It’s tempting to look at his long, later solo career—roughly 1988 to the present—and celebrate his personal recovery from various forms of addiction, his emotional stability, his desire to write and perform, while regretting the music he has written. But that’s a little like being disappointed that his astonishing voice—so high and gilded on the early records—wasn’t as pure at age seventy-eight (when Long Promised Road was filmed) as when Wilson was in his early twenties. (In 2004 the critic Robert Christgau called it “soured” and “thickened.”)

Having the profound influence Wilson had for as long as he did in the 1960s is miraculous in itself. In Long Promised Road, an interviewer—after a 1964 concert in Oklahoma—asks him where he gets the “incentive” to write his songs. “We’re in the industry,” he says. “There’s a lot of groups competing with us, and you feel that competition.” The competition Wilson felt with the Beatles is well known. The Beach Boys were the most popular band in America until early February 1964, when the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show for the first time, and everything changed. Wilson was amazed by the American version of Rubber Soul—by the unity of the album and the fact that none of the songs were filler. That led directly to the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, which in turn amazed the Beatles and helped inspire Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

But Wilson wasn’t only competing with John Lennon and Paul McCartney. He was competing in the studio with his idol, the producer Phil Spector, and in a sense with George Martin, the Beatles’ producer. He was struggling with the constant demand from Capitol Records (also the Beatles’ American label) to continue delivering hit songs of the kind that had made the Beach Boys popular—songs about surfing, cars, summer, girls—a demand summed up in the title of their 1968 song “Do It Again.” He faced a similar pressure to stick to the Beach Boys formula from other members of the band, especially his cousin and lead singer Mike Love, the antihero of the Beach Boys saga.3

And, of course, he was forced to contend with his appalling father, Murry, an arrogant, insecure man who sat in obstreperously on recording sessions even after he was fired as the band’s manager in April 1964, when Brian was still just twenty-one. “I’m a genius too,”4 he’s heard telling Brian on tape during a session in February 1965. But Murry’s only genius was his crippling ability to mix praise, belittlement, and physical abuse. By 1967, as Brian withdrew into isolation after giving up on Smile, the successor to Pet Sounds, he was trying to survive his own psychological fragility—a condition later diagnosed as schizoaffective disorder—which had been exacerbated by drug use. Musically speaking, he had always been fundamentally alone. The creative partnership you sense in Lennon and McCartney—even in January 1969, shortly before the band broke up—was largely missing from Wilson’s life.

This story has been told many times. Long Promised Road is merely the latest in a series of documentaries, including Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times (1995) by the music producer Don Was (who also appears in Long Promised Road) and Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson and the Story of “Smile” (2004) by the music historian David Leaf.5 These films follow a pattern: lots of talk with Wilson and lots of footage of him, in the film’s now, performing songs he’d recorded thirty and forty and fifty-plus years earlier. What changes is Wilson’s age and the musicians who are interviewed to explain why his music matters. In Was’s film, the list includes Thurston Moore, John Cale, Tom Petty, and Linda Ronstadt. In Leaf’s, we hear from Elvis Costello, Jimmy Webb, and Burt Bacharach. In Long Promised Road, Bruce Springsteen, Elton John, Nick Jonas, and Taylor Hawkins appear. Perhaps the saddest thing I can say about Long Promised Road is that it may be remembered more for the interviews with Hawkins, who died at age fifty in March 2022, than for anything else.

Advertisement

Inevitably, Long Promised Road is hampered by the passage of time. So many people who knew and worked with Wilson in his early twenties are now gone. Dennis and Carl, his brothers and fellow Beach Boys, died in 1983 and 1998. Most of the great session musicians Wilson worked with—like the drummer Hal Blaine, who appears in the two earlier documentaries I’ve mentioned—are also gone. Al Jardine, the original Beach Boys rhythm guitarist, who was locked for years in a legal battle with Mike Love over the right to use the band’s name, is given exactly one spoken line. Wilson begins to sound like a lone survivor, the last one left to tell the tale. And as the tale gets retold it gets thinner and thinner. The slightly shell-shocked quality Wilson often evinced in earlier interviews has now deepened. Each sentence he speaks seems to emerge abruptly from an unknowable remoteness.

The film’s makers also seem to assume that the audience isn’t actually interested in detail of any kind, musical or otherwise. A good example is the title. The song “Long Promised Road” appeared on the album Surf’s Up in 1971. In the film, we hear it playing on a car stereo as Wilson is being driven around Los Angeles, and we see it being rehearsed in the studio as the final credits blur past. It’s all too easy to come away with the impression that this is a Brian Wilson song. But it’s not. It was written by Carl Wilson and the Beach Boys’ former manager Jack Rieley. It was also sung by Carl, who produced the song and played most of the instruments on it.

At the heart of Long Promised Road is Brian Wilson’s friendship with the music journalist Jason Fine, who cowrote the film and has written several articles about Wilson for Rolling Stone magazine. On camera, Wilson and Fine have lunch at the Beverly Glen Deli, and Fine drives Wilson around LA—visiting his former homes and places like Paradise Cove, where the cover of Surfin’ Safari was photographed in 1962—while playing Beach Boys songs and asking questions Fine has surely asked many times before. Perhaps half of Long Promised Road amounts to a kind of dash-cam documentary. Watching those scenes feels like being trapped in a ghastly therapy session, especially the moments when Wilson is left to face on camera his grief over the deaths of Rieley and Carl Wilson. The contrast with the opening scenes of I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times—a voluble, happy Brian and his wife, Melinda, making a similar tour in a convertible—couldn’t be greater.

In short, though Brian and Melinda are listed as executive producers, Long Promised Road feels both vapid and exploitative. And worse, it has almost nothing of value to tell us about the actual music Wilson created. Only Elton John says anything about its technical innovation. He points out that Wilson’s bass lines—played in the studio by the great Carol Kaye—often start on the fifth rather than the root of a chord. This is something McCartney noticed in 1966 after listening to Pet Sounds, and it changed the character of his own bass playing.

The question I’m suggesting, a question completely bypassed in Long Promised Road, is whether the accomplishment of Wilson’s miraculous early years is enough for a whole lifetime. How do you best celebrate the life of a musician, now eighty, who will be remembered almost entirely for what he recorded by the time he was twenty-five?

It’s not terribly surprising—no matter how sad it is—that Wilson himself now has almost nothing useful to tell us about those amazing years from 1962 to 1967. Even to glimpse them he has to look back through some bitter, psychologically devastating times, including the nine years he lived under the manipulative supervision—a sort of house arrest—of the psychologist Eugene Landy, who took over in Wilson’s life the abusive role his father once played. In Long Promised Road, Wilson seems rightly focused on who he is now and on enjoying the prolonged reprieve he’s had since the emotional chaos of his youth. By continuing to perform before live audiences (including concert dates this past summer) he is, in a sense, accepting for himself, on his own terms, the magnitude of what he did when he was young. He is being, it seems to me, generous to himself.

And yet I can only listen to the original recordings and their various remasterings, not the note-perfect recreations of the recordings that audiences experience when they see Wilson in concert today. I have trouble accepting that Smile—the album he abandoned in 1967—was finally finished in 2004, because I question the continuity of the creative mind that “finished” it nearly forty years after it was begun. My skepticism makes me wonder whether I’m simply clinging to the memory of my own experience of the Beach Boys when I was young. But I don’t think so. They’re the same doubts that apply, say, to Wordsworth’s late revisions to The Prelude.

The joy I experience listening to those early Beach Boys records—through “Good Vibrations” and “Heroes and Villains” and slightly beyond—has nothing to do with nostalgia, with memories of where I was or who I was when I heard them. They don’t evoke for me an idealized California or even my adolescent yearnings. I don’t hear them from Osage or Sacramento. I hear them from now. Wilson’s songs still have the power to astonish on their own terms, from their own time. What makes them so remarkable isn’t just the artistic fulfillment they achieve. It’s the artistic promise they embody. You can feel the explosive, disruptive, but ultimately controlled power of Wilson’s musical imagination—usually in three minutes or less.

One of the best examples occurs on side 2 of Summer Days (and Summer Nights!!), which was released in July 1965. Everyone knows the first song on that side—“California Girls.” Wilson has said that its slow, deliberative introduction is the best music he ever wrote. And those opening bars, as many people have noted, feel like a direct link to Pet Sounds, his next album of original work, which appeared in May 1966. In a sense “California Girls” is almost too familiar now. It takes effort to rehear it without letting your memory elide or override what’s actually happening.

It’s the next song on the album that really interests me—“Let Him Run Wild,” which was also the B-side of the “California Girls” single. It’s not a song most people know well, but its spare, highly melodic instrumental track (which you can hear, isolated, on the strange 1968 Beach Boys album Stack-O-Tracks) is as full of musical augury as the opening passage of “California Girls.” In the opening bars of “California Girls” and the syncopated antiphony of vocals and backing track in the verse of “Let Him Run Wild,” you can hear musical strains unfolding that are fully realized in the jubilant instrumentation of poignant sadness called Pet Sounds.

In the 1995 Don Was documentary, Tom Petty reminds us how far ahead Wilson had to be thinking when he recorded his songs, given the complexity of his musical arrangements after early 1965. Petty is talking about the imagination needed to create highly sophisticated compositions involving multiple vocal and instrumental parts. But he also means the practical foresight required to hire all the studio musicians needed for a Brian Wilson recording session in 1965 or 1966. I think that’s a powerful clue to what’s often been called—uselessly—Wilson’s “genius.” We can feel the predictive power of “California Girls” and “Let Him Run Wild” because we know what followed, in Pet Sounds. But it’s still worth trying to imagine something that’s wholly unrecoverable: what Wilson himself must have felt as he looked ahead into how a song was developing, while discovering, intuitively, where that song would lead him next.

Wilson marvels, in one of the documentaries I’ve mentioned, how quickly he wrote the melody of a song like “Caroline, No.” To me, that’s a sign that he’s allowed himself to misunderstand—in wholly conventional terms—what’s most remarkable about his work. It isn’t the melodic line or the speed with which it was written that stuns me now and stunned me then. It’s the shape of the mind in which the intricate shapes of his music entangled and resolved themselves. That mind has only ever been captured in one place: in the music as Brian Wilson recorded it long ago. .

This Issue

October 6, 2022

The Slow-Motion Coup

A Powerful, Forgotten Dissent

-

1

Yes, “Kokomo” reached #1 in 1988. I don’t care. Brian Wilson had nothing to do with it. It was produced by Terry Melcher. ↩

-

2

Brian Wilson stopped touring with the Beach Boys in December 1964 after a nervous breakdown on a flight to Houston. Eight of the thirteen cuts on Beach Boys Concert are not original Beach Boys songs. ↩

-

3

His absence from all the Brian Wilson documentaries is notable. ↩

-

4

In October 1967, Capitol Records released The Many Moods of Murry Wilson, an album that is testament to his ability to irritate record executives. ↩

-

5

There are several other Brian Wilson documentaries, as well as films about the Beach Boys, including the documentary Endless Harmony (1998) and the docudrama Love & Mercy (2014), starring both John Cusack and Paul Dano as Brian Wilson. ↩