It always feels like an appropriate moment to talk about Buster Keaton, if only because talking about him leads naturally to watching his films and experiencing again the shades of awe and amazement they reliably awaken. The present occasion is the publication of James Curtis’s Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life, an encyclopedic biography that lays out his trajectory and vicissitudes in novelistic detail, and Dana Stevens’s Camera Man, a series of meditative essays that examine Keaton and his world from a multitude of vantage points.

These two quite different books complement each other nicely. Curtis keeps to a linear path, following Keaton as closely as the archives permit, from his beginnings as an infant vaudeville phenomenon to the long aftermath that followed his decade of triumph in the silent-film era. Stevens, by contrast, darts among adjacent or parallel lives (Mabel Normand, Bert Williams, F. Scott Fitzgerald) and events (the Wall Street dynamite bombing of 1920, the rise of movie fan culture, the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous), relating Keaton and his work to what she calls “the invention of the twentieth century.” If Curtis provides the chronicle (immersing us deeply enough to induce claustrophobia in recounting the dark years when Keaton’s career imploded), Stevens provides the brilliantly illuminating commentary, reflecting with its unexpected leaps the imaginative agility of his greatest work.

The two books join an already immense literature. As the most quintessentially silent of silent filmmakers, Keaton seems to provoke from writers a verbal adjunct to an art that so beautifully dispenses with words. It’s as if they were impelled—however quixotically—to complete with language what is already complete in itself. It is not enough to look at his films; there remains always the need to recount them, to recapitulate their gags in slow motion, to plot their mechanisms, to puzzle out how they were made, and to define (no matter how impossible the attempt) their singular effect. Is it a matter of geometric abstraction, of heroic physical feats accomplished without bravado, of a sublime and unsentimental hilarity shot through, in James Agee’s words, with “a freezing whisper not of pathos but of melancholia”? In the search for an appropriate analogy, Keaton has been likened to everyone from Abraham Lincoln to Franz Kafka. At the end of his life, finally showered with artistic recognition, he confided to his wife his wariness of “that genius bullshit.”

Keaton himself acknowledged no goal beyond making people laugh. Tricks and surprises his work offers in abundance, but there is no suggestion of deeper mysteries or perplexities, no appeal to mystical or socially redeeming sentiment—everything happens in plain sight, from setup to payoff, and when it’s done, it’s done. The search for a final meaning or ultimate moral lesson disappears into a void—somewhat in the way Buster disappears in Sherlock Jr. (1924), as he dives forward into a small valise held open by his assistant and is instantly and inexplicably swallowed up. (Typically for Keaton, this astounding gag was not a postproduction optical trick but a theatrical illusion, performed live, involving the deft use of a trapdoor.) “All his life,” as Stevens puts it,

Keaton remained completely indifferent to religion or metaphysics of any kind. His films stand as proof of his belief in the immanence of the material world, a place where the only higher powers are the laws of physics: speed, weight, force, gravity.

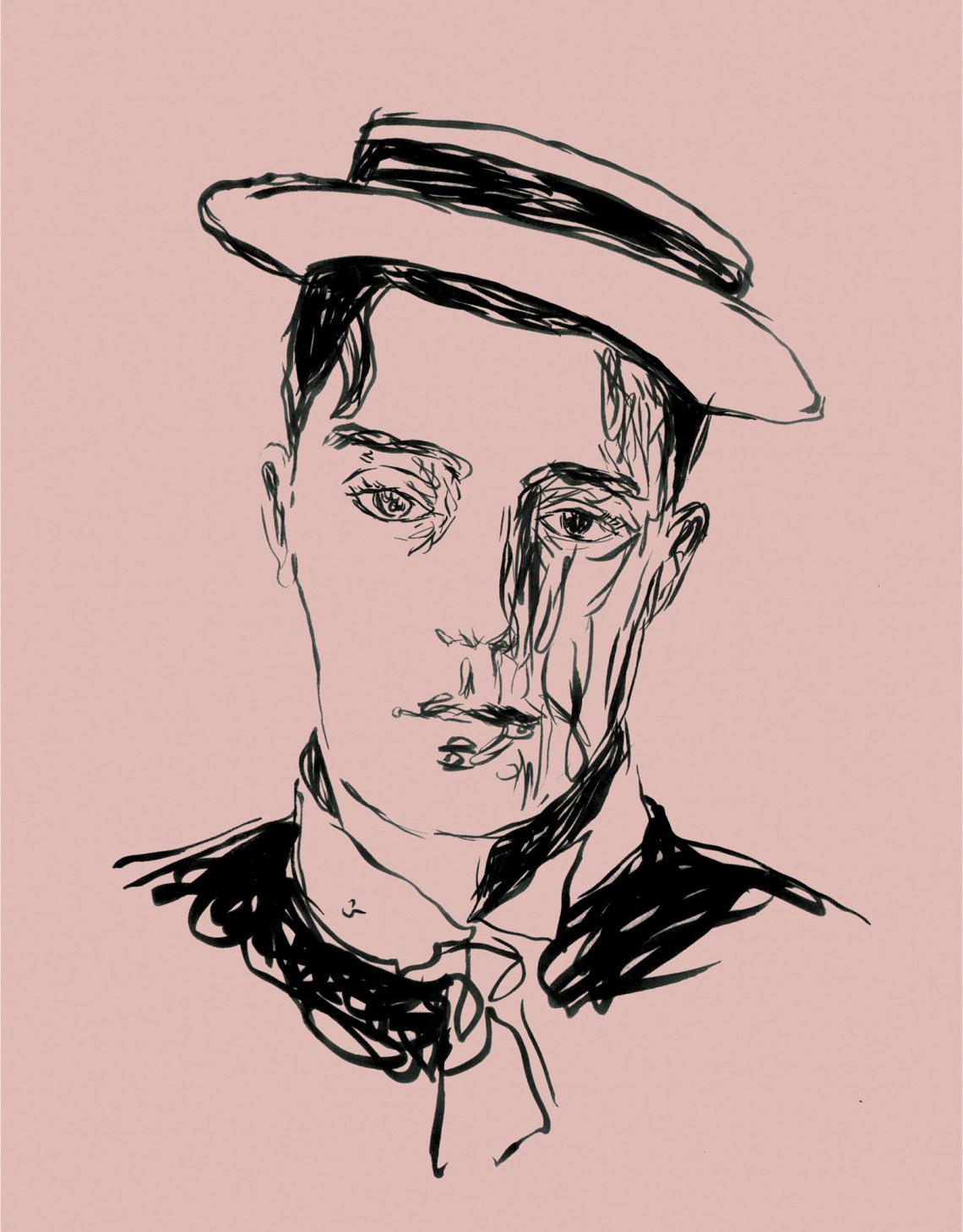

Yet there is no way to avoid the sense of the uncanny in contemplating Keaton’s one decade of independent filmmaking. In the 1960s, as his oeuvre, after decades of neglect, gradually reemerged into full view at museums, film festivals, and revival houses, he figured for many as an incomparably mysterious avatar. The mystery began with the face, the inevitable point of entry into any consideration of his art. It was his trademark in his heyday, however mischaracterized in publicity that identified him as the “frozen-faced comedian” or the “boy with the funeral expression.” Neither frozen nor funereal—nor blank nor immobile nor masklike—Keaton’s face is equally capable of expressing complacent contentment, inhibited longing, controlled panic, dawning awareness, unspoken sorrow, resigned acceptance, or the supremely focused attention of the scientist on the brink of a discovery or the gymnast calculating the geometry of a daredevil leap. In its subtle transitions it registers a wary reckoning with appearances that so often prove deceptive. In its prevailing calm it reveals itself also as a face of singular and at times almost otherworldly beauty.

The literary critic Hugh Kenner, appropriating Mallarmé on Poe, described Buster as “dropped to this earth from some obscure cataclysm.”1 He seemed indeed a visitor from elsewhere, as alien when boarding an antique railroad in a stovepipe hat in Our Hospitality (1923) as when emerging from the ocean in The Navigator (1924) in an imposing tanklike diving suit. Beyond the specifics of the roles he played—single-minded boat builder, hapless heir, daydreaming movie projectionist, friendless drifter, fiercely devoted railroad engineer—he incarnated a superior but detached intelligence, making his own kind of sense out of the perplexities of earthly existence in ways baffling to the terrestrials among whom he found himself. He operated with the clear-eyed genius of a very serious child discerning formal likenesses between dissimilar entities and inventing new and undreamt-of uses for common objects.

Advertisement

For all his fertility in superbly improbable inventions, what counted for Keaton was a sense of realness, an avoidance of the “ridiculous,” an adjective by which he indicated the disconnected gimmicks and anarchically unleashed aggression typical of Mack Sennett and Keaton’s own cinematic mentor, the ill-fated Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle.2 He insisted on gags that evolved logically, story lines “that one could imagine happening to real people”—imagine being the appropriate verb, and the logic in question being of a peculiar sort unique to Keaton. The predicaments of his heroes were made to seem not only plausible but inevitable, even when they involved being chased over hills and valleys by a mob of women in wedding gowns (Seven Chances, 1925) or guiding a herd of cattle through the traffic-clogged streets of Los Angeles (Go West, 1925).

The pursuit of realness was carried to extremes in the epic proportions of the landscapes he sought out, the use of actual ocean liners and railroad trains as comic props, the execution of stunts like making an eighty-five-foot jump into a net in The Paleface (1922) or standing motionless in Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928) while the façade of a building falls on him—he is saved only by a conveniently placed window opening. (“We built the window so that I had a clearance of two inches on each shoulder, and the top missed my head by two inches and the bottom my heels by two inches.”) Magic act merges with cinema verité in films that become documentaries of the impossible. The fantastic structures and machines have the stark authenticity of the handmade. Most authentic of all is Keaton himself, continually testing the limits of the body’s capacities, not with bravado but with a demeanor that could pass for self-effacement.

The mystery of the face begins in childhood, with the publicity shots of Little Buster, as he was billed at age six when he was already appearing professionally as part of his parents’ vaudeville act. There is not a trace of childishness in his sober gaze as he sports a bowler hat and a cane with mature gravity, or appears as the miniature double of his father with wig, beard, and corncob pipe, or (a stage veteran at age eleven) strikes a blasé pose in the curly locks and ruffles of Little Lord Fauntleroy.

To speak of “childhood” in the case of Keaton is admittedly questionable. His parents, Joe and Myra, met in 1893 in Edmond, Oklahoma, when they were both performing in a traveling medicine show. The randomness of Buster’s birthplace in 1895—the small Kansas settlement of Piqua—foreshadowed the peripatetic life he would lead until he was in his twenties, crisscrossing the country with his parents and two younger siblings, transitioning from medicine shows to vaudeville, and carving out a niche in the subculture of wandering entertainers that was to provide him with his only schooling. (As the English critic David Robinson put it in his pioneering critical study of Keaton, “He had the good fortune—rare in a civilised twentieth-century society like America—entirely to escape formal education.”3)

Joe Keaton, a high-kicking acrobat, specialized in elaborate stunts that involved leaping over chairs and tables; Myra provided comic diversion playing a saxophone. With these skills and any other devices they could come up with, they managed to make a living when such a living was still possible. The stage world they inhabited was both vast and marginal. Americans loved clowns, novelty acts, virtuosic eccentrics, but the life of such entertainers existed in a zone apart, just beyond the social worlds of the onlookers. Buster was onstage almost from birth, according to family lore “scuttling like a crawdad on a creek bottom” in the midst of one of Joe’s monologues and bringing down the house.

By the time he was six the act was billed as “Mr. and Mrs. Joe Keaton and Little Buster” and eventually, at their most successful, as “The Three Keatons.” Joe found a new slogan to advertise the act: “Keep Your Eye on the Kid.” Buster quickly assumed an equal and even predominant role, by the testimony of reviews in newspapers and trade journals, which singled him out as “a diminutive five-year-old comedian who is unusually funny,” “a laugh-maker,” “so clever…that there are many who believe him to be a dwarf.” A theater manager’s report from 1902, when Buster was seven, described “the laughs coming almost entirely from the little fellow, who is really very clever.” To contemplate that existence—forever on the road, forever performing in close collaboration with his parents, forever confronting fresh audiences of strangers—is to wonder about the formation of an inner life under such circumstances.

Advertisement

It was a realm of continual improvisation. “Every show’s a different show with us,” he reminisced years later. For Buster, who did not learn to read until age eight, it was also a realm of continual education. Vaudeville was a diverse and crowded world, and he absorbed as much as he could of all the arts and sciences that came into his view: tumbling, juggling, sword swallowing, wire walking, animal acts, magic tricks, card tricks, dialect humor, singing and dancing and playing the ukulele, impressions of other vaudeville performers. By all evidence, he mastered far more skills than he ever had a chance to demonstrate in his films, continuing to astonish people with casual displays of virtuosity until the end of his life. Above all, he learned how not to get hurt, or how not to make too much of it if he did.

What the Three Keatons offered was, in Buster’s words, “the roughest act that was ever in the history of the stage.” Buster’s role was essentially to cut up mischievously, teasing his father, getting in his way, tripping him with a broom, until Joe went after him to administer punishment, hurling him about the stage, into the scenery, and eventually into the audience. (As Curtis notes, “To facilitate the grace with which Joe threw Buster around, he had a suitcase handle sewn into the back of the boy’s costume.” The costume was also well padded.) The close attention of New York’s Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, determined to enforce an 1876 law that essentially prohibited children under seven from performing onstage, made things difficult for the Keatons, who used legal tactics and a range of evasive maneuvers in response; at one point, after Joe defied the society’s mandates with an unauthorized public performance, the act was banned from New York for two years. Buster had sometimes to submit to physical examinations to look for marks of injury or abuse that it seems were not found. Joe came up with another tagline to drive the point home: “The Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged.”

A passage in Keaton’s memoir My Wonderful World of Slapstick (1960) feels central to his life and art:

I could take crazy falls without hurting myself simply because I had learned the trick so early in life that body control became pure instinct with me. If I never broke a bone on the stage it is because I always avoided taking the impact of a fall on the back of my head, the base of my spine, on my elbows or my knees. That’s how bones are broken.4

What a school to have been born into, a kind of sink-or-swim academy of self-protection that to Buster seemed perfectly natural: “All little boys like to be roughhoused by their fathers…. Because I was also a born hambone, I ignored any bumps or bruises I may have got at first on hearing audiences gasp, laugh, and applaud.” It was like finding a serene self-assurance, a near invulnerability, in the heart of violent action. “He didn’t just hurtle through the air,” Curtis observes, “he took flight.”

Keaton’s mastery of the art of soaring can be seen in The Goat (1921), one of the most wildly inventive of his two-reel shorts. Buster, a fugitive from the law, is seated at a dining room table when he is confronted unexpectedly by a detective of enormous proportions who blocks the only way out. There is a tense momentary pause before Buster, in rapid sequence, sits up, jumps on the chair he is sitting in and onto the table, from which he vaults over his adversary’s head and flies through a narrow open transom over the locked door. Discussing this scene in her superb study of Keaton’s films, Imogen Sara Smith writes of

his acute sensitivity to the way the world is put together, and his instinct for how to fit his own body into the scheme. He was a civil engineer manqué and also the son of a man who specialized in leaping off the floor onto a chair balanced on a table. He knew how to judge distances.5

Through all the early years, life itself had been a stage act, and the act at its core was about the simulation, or something more than simulation, of violence. In the films, that risk of harm—of annihilation—continues to play out on a grander scale than was possible on a stage, as Buster barely eludes the unleashed force of river rapids, cyclones, restless cattle, high-speed trains, cannibals, a mob of policemen, warring Indian tribes, hundreds of prospective brides, or an avalanche of tumbling boulders. He undergoes catastrophes and dodges extreme risks by a hair with a grace positively angelic, as if he had done nothing at all. The risks were in fact quite real, and any number of films show him missing death by inches. A twelve-foot drop when he opens a door into the void in the crazily misconstructed house of One Week (1920) seems to have just missed causing him serious injury. He claimed to have performed the eighty-five-foot jump from the bridge in The Paleface only because he “didn’t want to show yellow before my own gang.”

In the scene in Our Hospitality when he is swept toward the rapids, he is actually in great peril, his holdback wire having broken. A stunt in Sherlock Jr. involving a railroad waterspout caused him a bad headache, explained only years later when an examining physician asked when he had broken his neck. As for the falling house façade in Steamboat Bill, Jr.—perhaps the most awe-inspiring stunt in film history—it self-evidently came off exactly as planned. “You don’t do those things twice,” Keaton remarked. A further dimension is added when we learn from Stevens that the day before that scene was shot, Keaton had been informed that the Buster Keaton Studio was being disbanded and that he would no longer function as an independent producer—the beginning of the end of his extraordinary era of creative liberty.

The violence could spill over. Buster’s father, angry over a complaint from a theater manager about a damaged chair, proceeded to systematically destroy the theater’s entire stock of stage furniture; not long after, taunted from the wings by the powerful impresario Martin Beck, he left the stage and chased Beck down West 47th Street, doing major harm to the Keatons’ career in the process. As Buster grew into his teens, the father-and-child routine grew harder to sustain, and Joe’s increasing alcoholism and general discontent turned their onstage confrontations into actual combat, with Buster using all his skills to keep his father at bay.

In the end it wasn’t Buster who rebelled but his mother. Myra was also taking hard knocks from Joe, and in January 1917 she persuaded Buster, then twenty-one, to slip away with her from Los Angeles, where the act was about to open, and leave Joe behind without a note. As she recounts this episode, Stevens notes the passivity, almost a submissive fatalism, with which he conducted himself at crucial turning points: “Buster would be faced with a few such decisive moments, and often—sometimes, though not this time, to his own detriment—he would leave the decision-making to someone else.” One might imagine him hurled through life as across a stage, studying the formal perfection of his flight and touchdown rather than his ultimate destination.

All those skills and all the vivid impressions Keaton made on vaudeville audiences across America would not even be a footnote if he had not found his way, shortly after arriving in New York, to the newly launched film studio on East 48th Street where Joe Schenk was producing features starring his wife, Norma Talmadge, and comedy shorts with Roscoe Arbuckle, the Sennett star who was now directing his own films. The first day he walked into the studio—in Keaton’s often repeated version—he bonded with Arbuckle, whose close friend and filmmaking partner he quickly became, and met Talmadge’s sister Natalie, whom he married a few years later. The marriage was something of a disaster, but the partnership with Arbuckle—they made fourteen shorts together between 1917 and 1920—confirmed him in his vocation. As Keaton later told it:

I had to know how that film got into the cutting-room, what you did to it in there, how you projected it, how you finally got the picture together, and how you made things match. The technical part of pictures is what interested me.

Arbuckle said of Keaton that he “lived in the camera.”

The films with Arbuckle, chaotically assembled though they are, have their share of gags that foreshadow what was to come, but a different degree of rigor and purposefulness becomes evident from the moment Keaton takes charge of his own starring vehicles with The High Sign in 1921. One Week (filmed after The High Sign but released before it), which details the misfortunes of newlyweds building a monstrously misshapen and unstable house with a mislabeled home-building kit, is a flat-out masterpiece whose flow of comic invention can support a lifetime of viewings. The theme must have resonated with Keaton, who had not had a proper home in all those years of childhood touring. (At the height of his stardom he constructed one of the most extravagant of Hollywood homes, an Italian-style villa whose grounds can be glimpsed in his otherwise dismal early talkie Parlor, Bedroom and Bath.) “For Keaton,” Stevens comments,

every potential home is a space of danger and transformation; no façade stays standing for long. Structures that seem to offer shelter and physical safety reveal themselves to be nothing but heaps of wood on their way to becoming splinters.

He was to return to this comedy of catastrophe, but One Week remains its unsurpassably compressed expression.

Keaton’s was an art barely written down—he worked things out in his head and in long sessions with collaborators who were also friends, the same way vaudeville routines were worked out. Arbuckle before him had likewise boasted of having “not a scrap of scenario paper in my studio.” Curtis and Stevens establish in great detail how closely Keaton worked with his gag men, technicians, and craftsmen, and how open he was to suggestions by anyone on the set. The atmosphere was relaxed enough to allow breaks for “a coupla innings of baseball or somethin’.” On set he laughed a lot and sometimes spoiled takes by cracking up. No one who took part in the making of his films seems to have complained about the experience; as his frequent collaborator Clyde Bruckman put it, “Buster was a guy you worked with—not for.” But there was nothing casual about a process that might involve purchasing an ocean liner and turning it into a film set for The Navigator or building a 250-foot bridge over an Oregon river in order to destroy it along with the train traveling across it for The General.

On a different scale, the first reel of The Play House (1921) features Keaton in a theater where he plays all the parts and all the members of the audience. A single shot of a nine-man minstrel line required cameraman Elgin Lessley to successively mask portions of the lens with absolute precision and, in Keaton’s words, “to roll the film back eight times, then run it through again. He had to hand crank at exactly the same speed, both ways, each time…. He was a human metronome.” A form of comedy that had begun as something like folk art evolved into scientific experiment pursued with an obsessive devotion of which the audience would not even be aware. They would never know what it took to make those shipboard doors swing eerily open and shut in perfect rhythm in The Navigator.

Many of the greatest moments required no technical complications at all: Buster at the dining table in Our Hospitality, looking out of the corners of his eyes at his tablemates, who have vowed to kill him because of an ancient feud; in Steamboat Bill, Jr., trying on a succession of hats to make himself look more manly in the eyes of his riverboat captain father, each hat making him look more absurd than the last; in The Cameraman (1928), sinking to his knees in the sand after an unscrupulous rival has stolen the affection of his beloved. He turns every action into the most elegant possible ideogram, whether by means of intricately conceived machinery or the barest of gestures.

The independence that made that possible came to an abrupt end when, at the advent of the talkies, he surrendered creative control to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. (It was a bad omen that studio head Louis B. Mayer did not think that Keaton was funny.) No longer in a position to concoct his own scripts, construct his own sets and contraptions, and choose his own locations, he allowed himself to be cast against type as an inept bumpkin in a series of thoroughly forgettable features. Increasingly heavy drinking led to MGM firing him in 1933; two years later, in October 1935, close to death from the drinking, he was admitted to the psychopathic ward of the National Military Home in Los Angeles.

This was not the end of the story: as Curtis emphasizes, Keaton eventually controlled his drinking, found work making comedy shorts for various studios, appeared in the Judy Garland musical In the Good Old Summertime (1949), toured Europe successfully as a live performer, and with the coming of television became a familiar face again, restaging old routines for Colgate Comedy Hour or The Ed Sullivan Show. He enjoyed a long and evidently happy third marriage to the dancer Eleanor Norris and lived to see the restoration and global celebration of his silent work. Working was a necessity for him and he never stopped doing it, whether it was a starring role in a Twilight Zone episode, a cameo in Pajama Party (1963), or a commercial for Shamrock motor oil.

All that information alleviates somewhat the sense of pain attached to Keaton’s loss of independence. His work instills deep affection in those who love it, and it is good to learn that he did all right in those later years. But that is personal history, far more remote than the living presence of Keaton in the nineteen shorts and twelve features of his great decade, works that escape from history altogether into an alternate space of free invention. It was an almost accidental freedom permitted temporarily by a particular pocket of opportunity. In his late interviews Keaton seems above all grateful to have had the chance to realize so magnificently the opening he had been given: “My God, in those days, when we made movies, we ate, slept and dreamed ’em.”

This Issue

October 20, 2022

The Two Elizabeths

‘She Captured All Before Her’

Lucky Guy

-

1

See Mallarmé’s “Le Tombeau d’Edgar Poe”: “Calme bloc ici-bas chu d’un désastre obscur.” ↩

-

2

In detailing Arbuckle’s story, Curtis and Stevens support the evidence that tends to exonerate him of responsibility for the death of the actress Virginia Rappe following a party he hosted, an event that ended his career. Both emphasize Keaton’s loyalty to his friend at a time when many in Hollywood were eager to distance themselves. ↩

-

3

David Robinson, Buster Keaton (Indiana University Press, 1969), p. 8. ↩

-

4

Buster Keaton with Charles Samuels, My Wonderful World of Slapstick (Doubleday, 1960), p. 26. ↩

-

5

Imogen Sara Smith, Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy (Gambit, 2008), p. 80. ↩