Sinclair McKay writes at the start of his new book, Berlin, that the city displays its wounds openly, in walls pockmarked by bullets, in ruins and fragments, making no attempt to smooth “the jagged edges of history.” Kirsty Bell, in The Undercurrents, does not quite agree. She notes silences and gaps as well as visible scars. In her view of Berlin, the maze of stone blocks making up the Holocaust Memorial leads us openly into the depths, but the ruins of the Potsdamer Bahnhof, now planted over with grass, are an “anti-memorial,” a “promenade” where few care to walk, “a long green carpet under which the atrocities of the Second World War were swept, rail tracks, rubble, bones and all.”

Both authors are outsiders who know the territory well, but in different ways. McKay is a journalist and historian, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) and The Fire and the Darkness: The Bombing of Dresden, 1945 (2020). Bell is a writer and art critic who has lived and worked in Berlin since she left New York in 2001. Their radically different approaches, each amplifying the other, make the books fascinating to read in tandem.

McKay’s packed, driving narrative runs from World War I to the fall of the Wall in 1989. Determined not to divide the story into “hermetically sealed” eras—Wilhelmine, Weimar, Nazi, Communist—he asks how people’s mental landscapes and memories of particular neighborhoods remained firm “when the physical urban landscape around them was in a constant state of bewildering mutation and demolition.” The question gives a fresh immediacy to well-recorded events and cultural surges and reversals.

The lives of individuals thread through his book, bringing the history of the city alive. One is Paul Wegener, the sympathetic director and actor who depicted a haunting Jewish myth in The Golem (1920) and was later co-opted by Goebbels to appear in Nazi historical epics. In 1945, however, he took the title role in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s eighteenth-century play Nathan the Wise, a “heady plea for understanding that all three Abrahamic faiths were equal,” which had been banned throughout the Nazi era. It was a powerful symbolic gesture. Wegener’s career, McKay feels, displays the “reluctance or ambivalence” of many who toed the Nazi line simply to make a living and protect their families (and in Wegener’s case, five former wives).

An equally arresting figure is the imperious and demanding Duchess Cecilie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, the wife of Crown Prince Wilhelm, whose summer palace in Potsdam became the meeting place of Churchill, Stalin, and Truman in July 1945. Demonstrating the survival of extreme class divisions under the Reich, the duchess’s story also illustrates the contrast between those aristocrats who resisted and conspired against Hitler and those who colluded awkwardly with the Nazi regime, forming a “sometimes ironical pageant of high society.”

Most telling of all, however, are the recollections gathered by Berlin’s remarkable Zeitzeugenbörse witness project, including those of the schoolgirl Christa Ronke, whose greatest fear, as the bombs fell, was that she had lost her family’s ration cards, and who says bluntly of her rape by a Russian soldier that she “staggered a little with disgust but was glad to be alive.”

Bell too makes graphic use of varied sources, from the nineteenth-century paintings of Adolph Menzel and the fiction of Theodor Fontane to the writings of Christa Wolf and W.G. Sebald, the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and the concerts of David Bowie. She writes particularly well about the situation of women, whether maidservants in the 1860s or feminists in the 1960s. In contrast to McKay’s, her perspective is intimate and personal. Berlin is the city where she married and where her two sons were born, and she sees herself as “a reader rather than a historian” of her adopted home.

The Undercurrents begins in her apartment, with a mysterious pool on the kitchen floor, emblematic of both the imminent collapse of her marriage and the sandy, watery subsoil of Berlin, its name deriving from brlø, the Slavic word for swamp. Bell takes the advice of the Berlin-born Walter Benjamin: “It is undoubtedly useful to plan excavations methodically…. Yet no less indispensable is the cautious probing of the spade in the dark loam.” She starts

trawling and sifting through the past, without knowing really what to look for. Retrieving memories that aren’t your own is a messy business full of traps. But perhaps it can elucidate the porosity of a place and how its past affects its present?

Slowly she tracks the story of the Salas, the family who owned her building—luxury paper manufacturers, printers, and creators of card games. As she looks across the city from her kitchen window, the scene widens. Wandering the streets, exploring archives, delving into books and watching films, talking to the many people she meets, she finds the past unfolding around her.

Advertisement

Her beguiling account, although compressed, has a longer time span than McKay’s, charting the city’s growth in the nineteenth century. Her window overlooks the Landwehr Canal, originally a defensive ditch dug in the 1400s, when the Hohenzollern family took over the old market town. In 1850 it was turned into a tree-lined shipping canal cutting across the city, the vision of the landscape architect and city planner Peter Joseph Lenné, who also transformed the Hohenzollerns’ hunting grounds in the nearby Tiergarten into a romantic Garden for the People. Of the Tiergarten’s 200,000 trees, only 700 survived World War II and the hunt for firewood that followed: everywhere in the city is touched by twentieth-century violence. On the canal bank Bell finds a bronze plaque commemorating the recovery of Rosa Luxemburg’s body from the water on June 1, 1919, five months after she and Karl Liebknecht, the Communist leaders of the Spartacist uprising, were murdered by thugs of the Freikorps, one of the right-wing militias that sprang up after World War I.

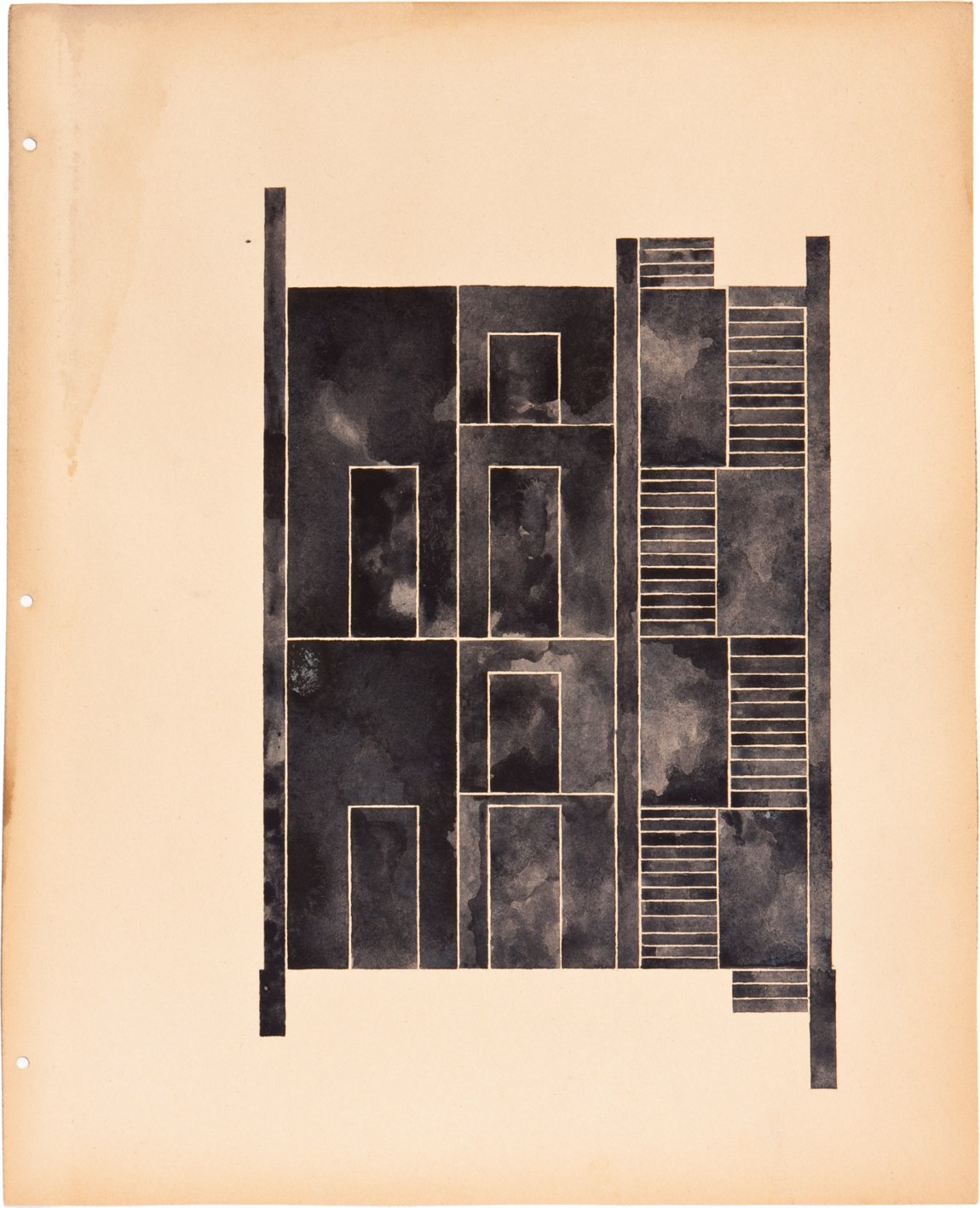

The workers who joined the 1919 uprising were heirs to Berlin’s rapid, unchecked industrial and commercial growth. In the grid of streets designed in the 1860s, thousands of Mietskasernen—rental barracks—arose. The rich had the spacious front apartments, while the poor packed into the gloomy, damp, ill-ventilated side wings and yards behind. The Häusermeer der Stadt, Benjamin called it—the city’s sea of houses. Like islands in the middle of this sea stood the two great train stations: the Anhalter Bahnhof with its elaborate façade and the Potsdamer Bahnhof, vital nodes in a network of rail lines that crossed the German Reich. A fragment of the Anhalter’s bomb-crushed façade remains as a memorial, writes Bell, “a free-standing remnant that seems to exaggerate the uncanny lack of a building behind.”

By the 1880s Berlin had the highest urban population density in Europe, but pleas for help from tenement dwellers desperate about their living conditions went unheard, the Prussian authorities choosing repression over reform. In reaction, the Socialist Labor Party, founded in 1875, mobilized the voting power of migrants and workers. By 1890, Bell notes, “‘Red Berlin’ (the ‘Red Menace’ to some, including Reich Chancellor Bismarck) had come into being.” Revolution came in the bitter final days of World War I. In November 1918 Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and fled to the Netherlands, and a republic was declared. At the beginning of 1919, after weeks of dissatisfaction on the far left with the provisional government, the Spartacists took to the streets, only to be quickly, brutally suppressed.

The constitution of the Weimar Republic was ratified in August 1919. Berlin was suffering the combined impact of war, civil conflict, and the Spanish flu, and soon it was flooded with refugees from the east, including a large Jewish community. Throughout the 1920s poverty was extreme, infant mortality higher than anywhere else in Europe. Violence proliferated, including headline-making murders. Yet in the Weimar years, McKay tells us, Berlin was a “city of light.” Neon signs flashed from 1922 onward, the Osram light-bulb company staged flamboyant displays, the towers of the huge Karstadt department store, nine stories high, blazed against the dark, and the carousels of the “hypermodern” Luna Park whirled under glowing lemon-colored globes. “The whole town was like a fairground,” wrote the novelist Erich Kästner. “The housefronts were bathed in garish light to shame the stars in the sky.”

At the same time Berlin was the site of the visionary housing projects of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and the modernist designs of the Bauhaus group, led by Walter Gropius, who moved there in 1928. Gropius and Mies were both forced to emigrate with the rise of Hitler, whose favorite architect was no modernist but Albert Speer, who dreamed of rebuilding the city into the “vast neoclassical Germania,” envisaged as enduring for centuries, its ruins cloaked in ivy a thousand years hence.

McKay deftly sets the heady Weimar era against the trauma to come, dramatizing the velocity of change and Berliners’ sense of the ground shaking beneath their feet. Writing about the “Uranium Club,” he examines the dilemmas and choices of Berlin scientists. These range from Albert Einstein, who spoke out courageously against what Sinclair calls the “increasingly poisonous” politics of the 1920s, to Max Planck and Lise Meitner, who tried in vain to continue their work by making accommodations to the regime, and those who flourished, like the physicist Werner Heisenberg and the pioneer of rocketry Wernher von Braun (both of whom later vehemently denied that they had endorsed Nazi beliefs). Turning to artists and writers, McKay looks at the savagely satirical, sensual work of George Grosz, a Dadaist, dandy, and committed Communist, regarded by the Nazis as “cultural bolshevist number one,” his work derided as obscene and degenerate.

Advertisement

Many in the city were proud of its cosmopolitan mix of people, its cultural and sexual freedoms, its bars and cabarets. Probing the mood of the time, McKay turns to film: to directors like Ernst Lubitsch; stars like Marlene Dietrich; films such as Faust, The Last Laugh, and The Blue Angel; and the playful early movies of Billy Wilder. These were markedly different from the films that mesmerized Hitler and Goebbels: Fritz Lang’s Wagnerian epic Die Nibelungen (1924) and his futuristic Metropolis three years later, with its “bi-planes and monorails and, down below, labourers enslaved to demonic engines that powered the city above.”

In the early 1920s rampant inflation meant that “the accepted structure of civilization—the simplest act of shopping for food—simply melted.” By 1931 a quarter of Berlin’s population was unemployed. Goebbels’s newspaper, Der Angriff, was disseminating virulent anti-Semitic propaganda, and violent encounters were building between the National Socialists and the Communists, the two “parties of the young,” as remembered by the British historian Eric Hobsbawm, then a committed Communist schoolboy whose family lived in the city.

Both these books sift the lies and secrecy, the levels of complicity with and resistance to the Nazi regime. We share Bell’s dismay when she discovers not only that card games produced by the Salas in the late 1930s included one called the Führer-Quartett but that one of the Sala brothers became a Nazi Party member in May 1932, even before Hitler was appointed chancellor on January 30, 1933. After the burning of the Reichstag in February, all opposition was stamped out.

April 1933 saw the first measures that would bar Jews from the civil service and the medical and legal professions and that boycotted their business; later, Jews were banned from restaurants, parks, and cinemas. Many fled the city or chose not to return from abroad. Among those who left in 1933 were Hobsbawm, Wilder, and Grosz, as well as Hannah Arendt, who was denounced by a librarian at the Prussian State Library while researching the extent of state anti-Semitism. After days in custody, Arendt and her mother fled to Switzerland. Einstein, who was in California at the time of the Reichstag fire, sailed for Belgium, declaring that as long as he had a choice he would “live only in a country where civil liberty, tolerance and equality of all citizens before the law prevail. These conditions do not exist in Germany at the present time.”

The deportations started, covertly at first—the young Brigitte Lempke was simply told that a friendly neighbor had gone to play the trumpet in “some kind of camp in Poland.” But as McKay notes, while Berliners might have claimed ignorance of the disappearances or the camps, no one could be unaware of the murderous anarchy of Kristallnacht in 1938, the glass-smashing destruction of Jewish businesses, the burning of houses, shops, and synagogues, the killings and lynchings. For three years, from June 1942 to March 1945, deportation trains left the Anhalter Bahnhof “at least every couple of days.” Their departures, Bell notes, were “scheduled alongside the regular early morning commuter traffic.” In the City Museum for Science and Technology she found a collection of train carriages, tracing the history of German railways. Among them—an anomaly in a city where exhibitions often gloss over the war years—is “a wooden-slatted wagon made for transporting cattle,” used instead to carry the city’s Jews to their deaths. “Here it is, in all its dumb materiality.”

The crucial hinge of both books is the fall of Berlin in the spring of 1945, “one of those moments,” McKay writes, “that stands like a lighthouse; the beam turns and sharply illuminates what came before and what came after.” Under ceaseless Allied bombing Berliners sheltered in cellars and subway stations, emerging under skies gray with dust and smelling of death. (In 2022, videos from Ukrainian cities bring such scenes appallingly close—not past history at all.) The Russian advance, McKay notes, was greeted with black Berliner humor: “The LS initials signifying Luftschutz (air-raid shelter) were said to stand for Lernen schnell Russisch, or ‘Learn Russian quickly.’” As the Russians encircled the city, its defenders were old men and baby-faced boys. Women tried in vain to hide from sexual assault—it is estimated that there were around half a million rapes—and an epidemic of suicides accompanied the city’s fall.

By early May makeshift Cyrillic street signs abounded. Within a fortnight of VE Day, May 8, the cinemas were showing Soviet comedies and glowing documentaries about collective farms. That summer, before the Allies arrived, the city’s riches were stripped, from Old Masters to industrial equipment and promising scientists. Berlin, writes McKay, “was picked apart like a chicken carcass.” Soon it would be carved up again, into different zones: Russian, American, British, and French.

In the ruined, disease-ridden city, men and women struggled to make a living. The black market flourished. People could move freely between different zones, sampling contrasting strategies of “denazification.” The Americans offered chewing gum and blaring swing music but also sternly accusatory films juxtaposing shots of the death camps and Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935). The Russians were subtler, with concerts of Beethoven and Brahms appealing to a continuity with the pre-Hitler past. The British, with staggering insensitivity, not only showed films of Dickens novels—including David Lean’s Oliver Twist, starring Alec Guinness as Fagin (complete with prosthetic hook nose)—but also staged a military parade lit with the flaming torches and searchlights that had marked Nazi rallies.

West Berlin was an island surrounded by Russian-controlled territories. It was far from clear what lay ahead. Frustrated in their expectation that the Allies would withdraw, the Soviets resorted to intimidation, cutting off electricity and setting up rough barbed-wire barriers. In 1948, when the Americans introduced the Deutschmark to replace the old Reichsmark and railway workers in East Berlin demanded payment in the new currency, the Soviet response was a complete blockade, alleviated only by the extraordinary yearlong British and American Berlin Airlift.

A week after the blockade was lifted on May 12, 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany was created, giving West Germany its own constitution; in October the Soviet-controlled east became the German Democratic Republic. Although increasingly patrolled, the borders remained open and workers from East Berlin commuted daily to the west. Many thousands more people, however, crossed from Soviet territories seeking asylum. To stop them, work began on the building of the Wall in the summer of 1961. “By 2.30 a.m. on 13 August, the two halves of the city were sealed up against one another,” McKay writes. Some Berliners, Bell notes, called it the “Wall of Shame,” but in the east it was officially an “antifascist protection barrier.” On the GDR’s city maps, West Berlin was just a blanked-out area, so that “wherever you are in West Berlin, if you drive straight ahead, you reach a dead end.”

“The binary suggested by the dividing of Berlin is misleading,” Bell comments. “The process is more like the division of cells. Varieties of difference proliferate.” Throughout the cold war, while Walter Ulbricht’s GDR government imposed control through surveillance by the Stasi—the secret police—bringing constant dread of betrayal and denunciation, the regime did provide housing and work, although labor protests grew. In some surprising respects, such as the legalization of homosexuality in 1968, East Berlin was in advance of the rest of Germany. On both sides liberty was relative: in Berlin and West Germany (as in the UK and the US) women’s pre-war freedoms fell before a reactionary conservatism. A government report of 1966 decreed that a woman’s main role should be as

caregiver and comforter, symbol of modest harmony, bringing order to the reliable world of the private sphere. Women should only engage in gainful employment and social commitment if the demands of family life allow it.

Bell is especially illuminating about these years, writing vividly of wilderness idylls in bombed-out spaces; of campaigns against grand plans for inner-city freeways; of the songs of Ton Steine Scherben, “the soundtrack to West Berlin’s anti-establishment and anarchist movements” in the 1970s; of the housing crisis and the squatters. She writes too of the darker side, the heroin deaths that outran those of New York by 1978 and the kidnappings and assassinations of the Red Army Faction.

The divided city held the attention of the world. In the early 1970s, West German chancellor Willy Brandt’s determination to build better relations with the GDR brought some relaxation of tensions. But the deaths and injuries of those who tried in desperation to cross from east to west would continue for years, until the night of November 9, 1989, when euphoric Berliners danced on the newly opened Wall, before the souvenir hunters began hacking at the concrete.

McKay’s fine account ends at that point, but Bell carries on to the brink of the present, tracing the steps to reunification, the lingering suspicions and hostilities, and the mistakes and triumphs of planning. Her personal quest and psychogeography of the city—a study of tumult, shock, shame, and denial followed by confrontation and increasing openness—take her down routes outside conventional history writing. In its artful spontaneity, The Undercurrents belongs with other examples of contemporary writing that uses walking, drifting, or even taking a bus as a mode of exploration, and often of healing. To understand the insistent pull of the city’s spaces, she turns, for instance, to feng shui, to the “grey energy” that architects detect in building materials, and to role-play and the “Stone Tape Theory,” a mode of channeling inherited trauma.

These excursions can be distracting, yet Bell’s “drifting” technique works well in piecing together scattered, partial images—“not to reconstitute past lives, or repair the broken pieces” but to bear witness. Every step, every stone in Berlin is weighted with a history that we need to read and understand, yet the city is also rich with music, art, a mix of cultures, and opportunities. Bell’s intriguing book, like McKay’s more considered account, recognizes this, while evoking the struggles of the past to build a story as “sprawling and unruly” as Berlin itself.

This Issue

October 20, 2022

The Two Elizabeths

‘She Captured All Before Her’

Lucky Guy