The French anthropologist Nastassja Martin is lying on a misty Siberian steppe, surrounded by “wads of brown hair stiffened by dried blood.” While she waits for the arrival of a Russian army helicopter, she wonders about “how to survive despite what I have lost in the other’s body, how to live with what has been left behind there.” Her loss is literal: a Kamchatka brown bear “went off with a chunk of my jaw clenched in his own.”

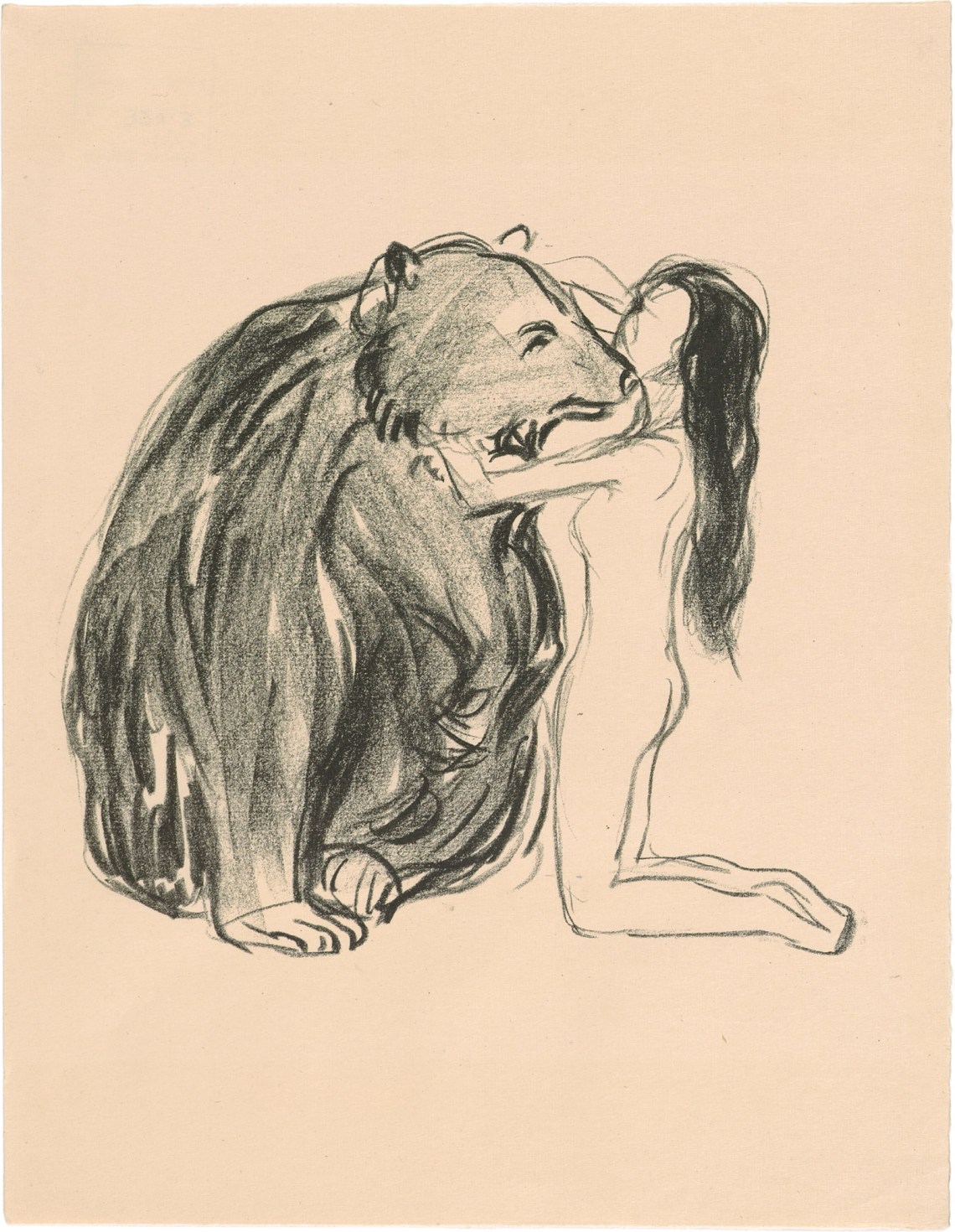

Throughout her memoir, In the Eye of the Wild, Martin never calls this encounter an attack. Instead, she describes it as a meeting, an implosion of boundaries, a melding of forms, and, most notably, “the bear’s kiss”: “His teeth closing over me, my jaw cracking, my skull cracking…the darkness inside his mouth.” Her word “kiss” is both emotionally subversive—almost erotic—and also insistently physical. Their contact involved “the moist heat and pressure” of his breath, the dark interior of his mouth. “His kiss?” she writes. “Intimate beyond anything I could have imagined.”

In the Eye of the Wild narrates the events that delivered Martin to this fateful “kiss,” as well as its arduous medical aftermath: a series of reconstructive surgeries in Russia and France, infections and recoveries, doctors with conflicting strategies. Throughout these procedures, Martin experiences a strange nostalgia for the connection she felt with the bear: “I was the one who walked like a wild thing along the spine of the world—and he is the one I found…. There was me and him and no one else in that moment…our bodies were commingled, there was that incomprehensible us.”

By the time of their encounter—in 2015, when Martin was twenty-nine—she was no stranger to the Siberian wilderness. She had already spent years on the Kamchatka Peninsula, studying and living with the indigenous Even peoples. After the attack, her Even friends, an adopted family of sorts, call her medka, an Even word “used to indicate people who are ‘marked by the bear,’ having survived their encounter with one…. People called medka are considered to be half human, half bear.” Martin dedicates her book “to all creatures of metamorphosis” and describes her own emergence as a new kind of creature, “features subsumed beneath the open gulfs in my face, slicked over with internal tissue, fluid, and blood: it is a birth, for it is manifestly not a death.”

In the Eye of the Wild is a book about translation—the desire to translate trauma into meaning, or animal consciousness into legible interior life—and Sophie R. Lewis’s translation from French into English preserves the quicksilver nature of Martin’s voice as it flickers between droll understatement, furious indignation, reverential incantation, and wry humor. (She relishes telling a man pushing her wheelchair through a Moscow hospital, “I had a fight with a bear.”) This is also a book about tonal metamorphosis: no single, static affect—mournful, deadpan, awestruck—could suffice.

While the English title, In the Eye of the Wild, conjures a sense of otherness—animal eyes glimmering darkly in their sockets—the original French title, Croire aux fauves (Believing in Beasts), is an invitation to look into this wild gaze, to believe in the possibility of some communion. Martin acknowledges that her own impulses toward “building connections, analyzing and dissecting, fashioning a survivor’s castles in the air” are also coping mechanisms for surviving her trauma, and she seems acutely aware of the potential skepticism of her readers, who might wonder what delusions are at work when a person describes her gruesome mauling as a kiss. But she remains committed to understanding her attack as an experience of transformation rather than destruction. “The event is not: a bear attacks a French anthropologist,” she writes. “The event is: a bear and a woman meet and the frontiers between two worlds implode.”

Martin implies that the sensational headline version of what happened to her—Bear attack!—is a crutch that allows people to avoid the more uncomfortable question she keeps returning to instead: “What truly do I share with this wild creature, and since when?” Martin looks at her face and sees not a disfigured woman but a medka materialized: “I’ve never looked more like my own spirit.”

Martin refuses familiar scripts of human–animal interaction just as she resists the familiar stories of recovery that usually proceed from trauma. Rather than telling a story of damage and repair, she describes damage compounded by various attempts to repair it—from the grim Soviet-era hospital in Petropavlovsk (the capital of Kamchatka and the second-largest city in the world inaccessible by road), where her face is reconstructed with a metal plate, to her return to France, where surgeons at the Salpêtrière deem her “Russian-style” plate unwieldy and replace it with one of their own. (This second plate infects her with a strain of streptococcus that leaves her with a “ganglion” that eventually has to be removed as well.)

Advertisement

The memoir carries elements of body horror, tracking all these subtractions and removals. Martin often feels gawked at. The night after the attack, at a small army medical clinic, a man—maybe clinic staff, she’s not sure—barges into her room and starts snapping photos of her broken face. “Horror does have a face,” she thinks, “and it’s not mine but his.” She laments how “humans have this curious mania for attaching themselves to the suffering of others, like oysters to their rocks.” Amid all these “oysters”—medical caregivers, therapists, anonymous strangers—she finds herself missing the bear: “I’m the one going through these medical ordeals because there was an ‘us.’ There was me and him and no one else in that moment.”

She describes more agony in the medical aftermath than in the attack itself; it’s the bear who mauls her but the humans who truly harm her. They see her as a cripple, a contagion, a symbol, a crisis, or a freak; they assume her disfigurement has made her a compromised version of herself. After one young nurse with a “malevolent stare” injects food down her feeding tube “suddenly, brutally into my stomach,” Martin reflects that it “seems they’ll make me pay dearly for my survival in woman-versus-bear.” It’s not ultimately her survival she feels punished for, but her refusal to see herself as a victim.

When Martin decides to leave France and return to the wintry forests of Kamchatka, four months after the attack, she is also turning her back on the more recognizable version of her story—a medical saga of affliction—and embracing another genre entirely: a folktale in which a she-bear has finally risen to meet her destiny. Martin is asking us to believe in beasts—not to project our human explanations onto their behaviors or write them off as terminally opaque, but instead to embrace uncomfortable models of communion. What can we learn, Martin asks, when the familiar boundaries between humans and animals collapse?

In the Icelandic director Valdimar Jóhannsson’s film Lamb, a farming couple begins to raise a newborn lamb as if she were their own: bringing her into their home, feeding her from a bottle, rocking her to sleep in their arms. They name her Ada. Only later do we realize they are grieving a human daughter, also named Ada, who died several years earlier.

Like In the Eye of the Wild, Lamb tells a story about crossing the boundaries between species—through caregiving, in this case, rather than combat—and invites us to dwell in the menace of this transgression. (The film was billed as “folk horror” when it was released in America last October.) Lamb opens with tenderness where In the Eye of the Wild opens with violence, but both stories maintain that tenderness and violence are impossible to disentangle. Martin calls her mauling “intimate beyond anything I could have imagined.” Jóhannsson asks us to recognize the violence embedded in loving a creature that is not yours to love.

The first frames of Lamb juxtapose wildness and domesticity: long-haired sheep brace themselves against flurries of snow while a woman stands at her kitchen sink, her features flickering in candlelight, holding a pot roast. (As the theorist Donna Haraway has observed, the most common way humans relate to animals is by killing them.) The film shows a series of familiar human–animal “relations”: the couple, Ingvar (Hilmir Snaer Guðnason) and Maria (Noomi Rapace), wear appealing wool sweaters; they fry meat; they fill the sheep barn with hay; they have a cat who meows for more milk; they have a pet dog (they call it Dog). They don’t speak much, and they don’t say a word to each other when they first encounter Ada as a newborn lamb. They just exchange a glance and silently agree that they must start taking care of her.

We follow Maria and Ingvar through a montage of archetypal parenting moments: Maria swaddles the baby in a blue plaid blanket. Ingvar watches his wife singing to her and rocking her to sleep. They bring in a wooden crib from the garage—a relic of their lost daughter, we eventually realize—so their baby can sleep beside their bed. It’s all saccharine cliché: the only remarkable part of the tableau is that—as in a picture book—the baby is a lamb.

We first learn the baby’s name when she goes missing and her parents call out for her—“Ada! Ada! Ada!”—and we first see her full body when they find her lying in a misty field. Although she has the head of a lamb, we see then that the rest of her body has always been human. (Her right arm has a hand with fingers, her left has a hoof.) She exists somewhere between human and animal: not a she-bear, but a lamb-girl. As Ada grows into a child—shy and curious, wearing galoshes and a raincoat—her silhouette is simultaneously familiar and unnerving. She walks hand in hand with her parents across the craggy countryside, right into the uncanny valley.

Advertisement

Revealing Ada’s human body is a fantastical way of demanding that we see the expressive capacity of her lamb’s face. The cinematography demands this, too; when the camera gets close on the faces of the other sheep, they seem to be full of intense, startling shimmers of emotion—pleading, mourning, threatening. During some of the film’s longest stretches of silence, their facial intimations of grief and menace are what propel the plot. (The New York Times praised the film’s “Oscar-worthy cast of farm animals.”)

When Ingvar’s ne’er-do-well brother, Petur (Björn Hlynur Haraldsson), arrives at the farm, he’s initially repulsed by what he sees as “playing house with that animal.” He’s happier in a world of wool sweaters, lamb chops, and dogs named Dog. When Petur angrily confronts his brother about raising Ada as his own—“What the fuck is this?”—Ingvar answers with just one word: “Happiness.” It is emotion, Ingvar insists, rather than preexisting structures of relation, that can set the terms of engagement. Love itself—the brute, blunt, ferocious fact of it—becomes the fixed point that our familiar arrangements must rearrange themselves around.

But the old arrangements will not be refused so easily. In a series of wrenching scenes, Ada’s birth mother stands outside in the grass, beneath her daughter’s nursery window, bleating plaintively, and then aggressively, until Maria finally shoots the ewe with a rifle. At the climax of the film, when Ada and her father are out walking in the hills, Ingvar is shot by a wild creature who emerges from the mist—with a ram’s head and the body of a man. Here is Ada’s biological father, reclaiming his offspring from the false trappings of domesticity, bending over Ingvar’s bloody body to take Ada’s hand, leading her away into the wilderness. The ram-man uses the same rifle to shoot Ingvar that Maria used to shoot Ada’s mother; his murderous parental devotion is very much their feral ruthlessness, come back to haunt them.

The Times reviewer described Lamb as “an ominous warning about the danger of seeking happiness through delusion.” But the film doesn’t make it easy to decide who is more deluded: the couple who feel an intense kinship with this animal creature, or the brother—perhaps the viewer—who wants to banish any acknowledgment of this kinship entirely. When Maria stands over the dead ewe with a rifle, it’s a bit like watching the emergence of a medka: she hasn’t become a wild animal; she’s been one all along. As we discover Ada’s human limbs, we see more and more of her foster mother’s animal heart: primal, possessive, ruthless, predatory in her insistent caregiving.

In the Eye of the Wild and Lamb both suggest that we are bound to animals through love and terror: the sweet sheep-girl and the monstrous ram-man; the bear’s claw and the bear’s kiss. Looming in the margins of these stories about human vulnerability to animals is the darker reality of how vulnerable they are to us. Mostly, we are the sources of menace and the agents of pain—with our factory farms and our ravenous appetites, our reckless sense of entitlement to the natural world that sustains us all.

If Lamb is a folktale, does it have a moral? It takes the metaphoric violence of turning an animal into a symbol, a crutch, or a surrogate and makes it literal: the ewe killed with a shotgun, the ram-man’s bloody revenge. When we force animals into playing roles in the stories we’ve written for them, we are taking something that doesn’t quite belong to us—not just their bodies but their consciousness—and trying to make it ours. This claiming comes at a price.

Martin resists the violence of turning “her” bear into a symbol, particularly a manifestation of her own repressed anger, as one friend suggests to her:

What is going on here, for all the other souls around us to be reduced to mere reflections of our own states of mind? What are we making of their lives, of their trajectories through the world, of their choices?

She understands these reductions as attempts to impose false coherence, as if animals—and her own violent animal encounter—have to be “consumed and digested in order to make sense.” She herself is most interested in a more literal digestion: the bear who has absorbed part of her body, while she has, she believes—in her transformation into a medka—absorbed part of his.

Even as Martin fights the bear’s translation into totem, she implicitly makes her own assumptions about his consciousness—especially in her conviction that their encounter involved some kind of spiritual communion for him as well. While Lewis translates Martin’s description of the aftermath as an attempt to reckon with “how to survive despite what I have lost in the other’s body,” the original French phrasing, literally translated as “how to survive without what has been lost in the other’s body; how to live with what has been deposited there,” evokes a more reciprocal experience, as though both Martin and the bear have “deposited” something in the other.

Maria and Ingvar, marooned in the purgatory of their grief, are eager to absorb Ada in a different way—by constructing a family that includes her. But ultimately, Ada’s father will not permit this dissolving of her wildness. When he leads her into the hills, it’s important that we do not know where he is taking her, or toward what life. He’s not just liberating her from the confines of a human home but from the strictures of human storytelling, which can become yet another way to keep animals close. We can choose to believe that Ada was distraught when her monstrous father led her back into the wilderness—we want to believe she reciprocated the love of her human parents, we want to believe in the monstrousness of a creature that led her away from this love—but Ada’s face is ultimately the face of an animal, a face we cannot presume to read.

Bonds between humans and animals are easily sentimentalized—girls loving their horses, dogs devoted to their “owners.” This sentimentality, like a fever fighting infection, battles against the unspoken discomfort of connections we can’t quite understand. As Haraway argues, the notion of “unconditional love” from animals is a delusion that gives people solace in the face of all the “misrecognition, contradiction and complexity in their relations with other humans,” just as the sweet lamb-girl, wrapped in her plaid blanket, offers Maria and Ingvar refuge from their unbearable grief.

If the notion of unconditional love obscures the complexities of human–animal bonds, then these stories rupture its false solace. Part of their unnerving energy stems from their shape-shifting relationships to genre: In the Eye of the Wild reads like a memoir turning into myth, while Lamb morphs from folktale to horror. If genre is a mode of domestication—taking wildness and corralling it into familiar containers—then these hybrid stories re-wild our visions of human–animal intimacy. You think you know what story I am telling you, they say, but I am actually telling you another one.

In 1965 a woman named Margaret Howe Lovatt spent several months living with a dolphin named Peter in a flooded house: a laboratory on the Caribbean island of St. Thomas where a cluster of rooms had been plaster-sealed and filled with several feet of seawater. The ostensible purpose of their experiment—overseen by a neuroscientist named John Lilly and partially funded by NASA—was to train Peter to speak. They shared their flooded rooms twenty-four hours a day, six days a week. (For one day a week, Peter returned to his tank.) They shared the intimacy of relentless daily proximity (“When we had nothing to do was when we did the most,” Lovatt recounted in one interview), but their days together were exhausting and uncomfortable—isolating for them both. Peter eventually grew so sexually frustrated that he couldn’t focus on his “lessons,” and Lovatt began manually masturbating him. The experiment was written up in Hustler under the lurid headline “Interspecies Sex,” and fifty years later it is generally remembered for this: the spectacle of a woman masturbating a dolphin.

The notion of bestiality grips us with nausea, but the taboo also keeps us safe. It takes a vast, unsettling set of possibilities about animal intimacy and confines them to a concrete category that can be dismissed as perversion. But Lamb and In the Eye of the Wild transgress the boundary between humans and animals without resorting to the primal specter of bestiality, which has become, in its own way, familiar.

We know that Peter got off with Lovatt. But we don’t ultimately know what he got from her. We know that he died shortly after the experiment ended. He closed his blowhole and stopped breathing. It was death by broken heart, suggested the vet who oversaw his care during the experiment: “Here’s the love of his life gone.” (Even calling Lovatt “the love of his life” tries to domesticate their strange bond, slotting their relationship into the confines of a cliché.) Lovatt herself returned to the flooded laboratory years later to live there with her husband and children. They converted it into a house, but one imagines it slightly haunted—their traditional nuclear family shadowed by the ghost of a bond that could never be fully understood. As Martin might ask, What truly did this woman share with this wild creature, and when did it start?

Love is never fully symmetrical. “If equal affection cannot be,” W.H. Auden famously writes, “Let the more loving one be me.” And every consciousness, whether human or animal, loves differently. When we love animals, we love creatures whose conception of love we’ll never fully understand. We love creatures whose love for us will always be different from our love for them. But isn’t this, you might wonder, the state of loving other people as well? Aren’t we always flinging our desire at the opacity of another person, and receiving care we cannot fully comprehend? Well, yes.

This Issue

October 20, 2022

The Two Elizabeths

‘She Captured All Before Her’

Lucky Guy