The first written evidence of what is known in English as The Arabian Nights or The Thousand and One Nights dates from the early ninth century. Two damaged and discolored pages from a book called The Thousand Nights, discovered in Cairo but originally from Syria, sketch the primal scene of storytelling: a character named Dinazad asks Shirazad to tell her—if she isn’t too sleepy—a tale of “excellences and shortcomings, craft and stupidity.” There is no mention of the bloodthirsty King Shahrayar, who vows to deflower and then murder all the kingdom’s virgins after witnessing his wife’s infidelity, but the paper fragment is proof at least of Scheherazade’s existence some 1,200 years ago.

Books with similar titles and scenes are known to have circulated in the medieval Arab world, but the oldest surviving manuscript comes from the fifteenth century. This Syrian text, comprising three volumes (a fourth may have been lost), was the basis for Antoine Galland’s Les Mille et Une Nuits (1704–1717), the first translation of the Nights into a European language. Galland was an antiquary to Louis XIV, and his elegant French versions, in twelve volumes, appealed to courtly tastes for contes de fées, or fairy tales. The stories were also enormously popular. Galland’s versions were translated immediately into English as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments and helped create a vogue for “Oriental tales” that lasted well into the nineteenth century (a central strand of the history of the novel).1

There were two important Victorian translations of the Nights into English. The first was by Edward Lane, a prodigious lexicographer—his eight-volume Arabic–English dictionary is still relied on by scholars—who lived for a time in Cairo and wrote an early work of anthropology, Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836), before publishing his translation of the Nights in 1838–1840. Lane was appalled by Galland’s liberties with the originals. Instead of fairy tales, Lane viewed the stories as accurate reflections of Arab life, which he believed to be essentially unchanged since medieval times. His translation, based on a different Arabic original than Galland’s, is buttressed with footnotes on food, clothing, music, the law, and much else. Lane was also occasionally appalled by the stories themselves, which can get rather bawdy. “I here pass over an extremely objectionable scene,” runs a typical footnote.

Objectionable scenes were precisely what interested Sir Richard Francis Burton, polyglot explorer, friend of Swinburne, and self-appointed expert in the sexual practices of “the East.” Burton thought Lane’s versions of the Nights were “turgid and emasculated,” and he published his own “uncastrated” edition in 1885–1888—in fact, it borrows heavily from a previous translation by the poet John Payne—under the imprint of the Kama Shastra Society, originally founded to publish translations of Indian works like the Kama Sutra. Burton lingered on the episodes that Lane modestly passed over, and his own annotations—even more abundant than the lexicographer’s—culminate in a fifty-page essay on comparative pederasty.

“To be different: this is the rule the precursor imposes.” That is how Jorge Luis Borges, in his essay “The Translators of The Thousand and One Nights,” characterizes the genealogy of European translations—a “hostile dynasty,” in his words—from Galland’s tasteful fables to Lane’s chaste ethnographies to Burton’s fantastical and often racist erotica. Borges celebrated Burton’s version in particular, not for its sexual lore but for its “glorious hybridization of English,” which includes innumerable foreign words, faux-biblical idioms, and archaic obscenities. For Borges, Burton’s literary brio was proof of his “creative infidelity” (a resonant phrase, given the Nights’ concern with unfaithful spouses). He also enjoyed Burton’s commentary, which was “of an interest that increases in inverse proportion to its necessity.”

It is true that Burton’s gaudy English bears little relation to the Arabic of the Nights, which tends to be plain, conversational, and even a little threadbare—in other words, the idiom of folk literature. The standard contemporary English translation, Husain Haddawy’s 1990 version, is—as if to confirm Borges’s rule of difference—a sober performance with wonderfully few footnotes. Whereas Burton’s translation includes virtually every tale he could find a manuscript for—as well as some that he made up, such as “How Abu Hasan Brake Wind”—Haddawy confined himself to translating the first critical edition of the Nights, published by the scholar Muhsin Mahdi in 1984–1994 and based on Galland’s Syrian text.

Haddawy didn’t aspire to creative infidelity; he was scrupulously faithful to the oldest surviving Arabic original. (The same scrupulousness characterizes Malcolm Lyons’s 2008 translation for Penguin Classics, though it is based on a later and more fulsome Arabic manuscript.) I have taught Haddawy’s version in the classroom and never wished for another. It is readable and reliable, and contains most of the Nights’ best tales in a single volume. Burton supplies a colorful point of comparison, but it is hard not to read his translation now as Orientalist camp.

Advertisement

Yasmine Seale’s new translation of selected tales from the Nights is the first in English by a woman, but at first blush it isn’t a dramatic departure from her immediate precursors—no hostility here. Like Haddawy and Lyons, she has crafted a contemporary rendition that is sensitive to the Arabic and uninterested in exotic retouches. Reading her version more closely, however, one sees how much can still be done with these endlessly told and retold stories. The difference Seale’s translation makes is subtle but cumulative, and finally profound.

No single comparison can fully capture these subtleties, but here are the opening passages of Haddawy and Seale. First Haddawy:

It is related—but God knows and sees best what lies hidden in the old accounts of bygone peoples and times—that long ago, during the time of the Sasanid dynasty, in the peninsulas of India and Indochina, there lived two kings who were brothers. The older brother was named Shahrayar, the younger Shahzaman. The older, Shahrayar, was a towering knight and a daring champion, invincible, energetic, and implacable. His power reached the remotest corners of the land and its people, so that the country was loyal to him, and his subjects obeyed him. Shahrayar himself lived and ruled in India and Indochina, while to his brother he gave the land of Samarkand to rule as king.

And here is Seale:

The story goes (but God knows more than us about the truths of times gone by) that long ago, in the Sasanian age, two brothers ruled over the islands of India and China, and their names were Shahriyar and Shahzaman.

The elder, Shahriyar, was strong on a horse and bold with a blade, never beaten and never burned, quick to revenge and slow to forgive. His dominion spread to the corners of the land until the far edges fell under his sway, and he chose India for his seat, and to his brother he gave Samarkand.

Seale’s rendition is notably swifter, perhaps in deference to the tales’ origins in actual speech. Her phrasing is more concise—“the truths of times gone by”—and she accomplishes in three sentences what takes Haddawy five. While he gets tied up in the kings’ names and birth order, Seale trims her language without sacrificing clarity: we don’t need to be told twice that Shahrayar is older, and if that’s the case, then Shahzaman must be the cadet.

Seale is also livelier and more colloquial: “The story goes” rather than the wan formality of “It is related.” Haddawy’s adjectives describing the king, “invincible, energetic, and implacable,” troop by in a Latinate blur. A more literal rendition of the Arabic phrase that Haddawy renders as “invincible” would be “one who burns so fiercely you would not dare to warm yourself by his fire.” Seale wisely eschews literalism, but keeps things vivid by arranging a nimble series of alliterations, parallelisms, and antitheses. “Quick to revenge and slow to forgive” is especially suggestive, since it points to the tales’ broader interest in whether rulers can learn to be merciful (a suggestion somewhat muffled by Haddawy’s “implacable”).

The Arabic of the opening lines is written in saj‘, or rhyming prose, a common feature of medieval texts. Rhyming is easy in Arabic but not in English, and most translators, like Haddawy, don’t attempt it. (Burton, of course, can’t help himself: “In tide of yore and in time long gone before…”) Seale doesn’t try to reproduce all the rhymes, but we hear in her version delicate echoes of the original: goes, knows, ago in the first paragraph; land and Samarkand in the second. She also has an ear for Arabic phrases that sound attractively strange in English when rendered word for word. After Shahrayar learns of his wife’s infidelity, he is “so angry he could bleed.” (Haddawy has the more idiomatic but less interesting “his blood boiled.”) All these elements give Seale’s translation a texture—tight, smooth, skillfully patterned—that makes previous versions seem either garish or slightly dull by comparison.

One can always find choices to quibble with. Arabic manuscripts of the Nights are essentially unpunctuated. The stories unfurl like a scroll or an unbroken wave of words, without periods or paragraphs. Burton’s translation comes close to this effect. There are no paragraph indents in his edition, though he does supply punctuation. (It isn’t by chance that James Joyce consulted Burton’s Nights while developing the dream language of Finnegans Wake.) Haddawy uses paragraphs sparingly, while Seale’s translation is full of breaks, including one for every change of speaker. This makes her versions easier to follow, but it slows the narrative momentum she is otherwise careful to maintain. In the short passage quoted above, there is no good reason for the new paragraph.

Advertisement

Another feature of the Nights that has vexed translators is the poetry. There is no verse in the opening tale of the two kings, but Scheherazade “knew poetry by heart”—not just some poetry, but “the poems,” as the Arabic says—and once she takes center stage, almost every tale includes at least a few lines of verse. Characters in the Nights recite poetry to bewail their fate, to praise male or female beauty, or to show off their wit and learning. Certain poems reappear in different tales, suggesting shared themes or situations. Some were written by famous poets, but most are by hacks and copyists. Almost all are written in classical meters and monorhyme, in which all lines in the poem have the same rhyme.

The problem with the poems is that they rarely move the story forward, and most readers of the Nights are primarily interested in the twists of plot. Lane translates fewer than half the poems in his Arabic manuscript, and originally planned to omit nearly all of them. He renders the verse in ungainly prose and without rhyme. Burton includes all the poems as well as the rhymes, but even Borges made fun of his versions (e.g., “A sun on wand in knoll of sand she showed,/Clad in her cramoisy-hued chemisette”). Haddawy also includes the poems, rendering them into what he calls a “neoclassic” style: iambic pentameters and rhyming quatrains. He makes the daring decision—consistent with his rigorous commitment to the original—to have bad poetry in Arabic sound bad in English too.

Seale is choosy about which poems she translates, and ends up providing English versions of even fewer than Lane did. She is most drawn to those that appear, like arias in an opera, at moments of emotional intensity. But she tends to render these episodes of sentimental release or heightened perception in taut, elliptical lines. (This is also what she does in a collaborative translation of mystical verse by Ibn ‘Arabi, turning the Sufi love lyrics into a kaleidoscope of Sapphic-sounding fragments.2) Here, for example, is Seale’s rendition of an Arabic couplet describing a beautiful young man:

Slip of a thing

Whose hair and blaze

Are to the world

Brightness and shade.

No flaw his cheek’s

Round mark—

Anemone’s

Black heart.

Compare this with Haddawy’s version:

Here is a slender youth whose hair and face

All mortals envelop with light or gloom.

Mark on his cheek the mark of charm and grace,

A dark spot on a red anemone.

“Dichten = condensare,” writes Ezra Pound, citing a German–Italian dictionary, and Seale’s poetic is one of modernist economy: the art of knowing what to leave out. She keeps prepositions to a minimum and tends to avoid conventionally poetic words like “slender,” “mortals,” “envelop,” “gloom,” and “mark” (as a verb). Her clipped monosyllables allow “anemone” to bloom more fully. While Haddawy’s version reads like an example of schoolboyish eloquence—which is indeed what some of the original Arabic poems are—Seale’s half rhymes and two-beat lines record a flash of perception, a lovestruck glance. Their swift, objective tenor is the language of rapture.

The same virtues of speed and economy characterize Seale’s versions of sententious or aphoristic verse. There are many such poems in the Nights—in Arabic it is called hikma, or wisdom poetry—and the unexpected affinity between Seale’s modernist aesthetic and this medieval genre is one of her translation’s many surprising pleasures. Aphorisms, like jokes, are notoriously hard to translate. Here is Haddawy’s (intentionally clumsy) version of a young man complaining of the twists and turns of fortune:

My fate does fight me like an enemy

And pursues helpless me relentlessly.

If once it chooses to treat me kindly,

At once it turns, eager to punish me.

And here is Seale’s:

My fate is like an enemy:

It shows me only hate.

If once it stoops to kindness

It soon mends its mistake

Seale has written of her belief that translations of the Nights should reflect the fictional predicament of Scheherazade. The courageous and resourceful tale-teller is “literally telling this story to save her life.” This doesn’t mean the tales need to be told breathlessly or with Burton’s desperate theatricality. It does mean that they can never be boring—that something must always be happening in the language as well as the plot. Seale’s Scheherazade is neither an exotic Mother Goose nor a garrulous storyteller; she is an artist at work under the most unforgiving of deadlines.

It is unlikely that any translation will have the influence of Galland’s French edition, which established a canon of stories that has shaped our idea of the Nights ever since. There is no evidence that the tales of Sinbad belonged to the Nights until Galland published his versions—derived from a different manuscript than the rest of the tales—although they’re now inseparable from the wider collection. The same is true of “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves,” although in these cases Galland wasn’t working from any medieval manuscript. Instead he was translating stories relayed to him by a young Syrian Christian named Hanna Diyab, whom Galland met in Paris in the spring of 1709, just before publishing the final volumes of Les Mille et Une Nuits.

We now know quite a bit about Diyab, thanks to the discovery of a fascinating memoir he composed at the end of his life, recently translated into English as The Book of Travels, which includes a brief account of his meeting with Galland. During a sequence of storytelling sessions, Diyab told Galland more than a dozen tales—the Frenchman transcribed short versions of them in his diary—several of which Galland later worked up for his edition, though he never acknowledged their source. Scholars used to call these “orphan tales” (since there were no manuscripts for them), and they include some of the most popular: not only “Aladdin” and “Ali Baba” but also “Prince Ahmad and the Fairy Pari Banu” and “The Enchanted Horse.”

Paulo Lemos Horta, the editor of The Annotated Arabian Nights, is frank about the populist aims of his edition, one of which is simply “to bring together the most influential Arabic tales” of the Nights. But another ambition is to right a literary-historical wrong and acknowledge Diyab’s contributions. Horta, a scholar of the Nights’ European reception, has included all of Diyab’s stories published by Galland (Seale translates these directly from Les Mille et Une Nuits), along with English renditions of Galland’s initial diary versions. With all these texts in front of us, Horta suggests that we can better appreciate “the full range of Diyab’s storytelling” as well as the tales’ “hybrid authorship.”

Some of Diyab’s tales are undoubtedly popular, and it’s clear he deserves some credit as their author, but how good are they? “Ali Baba” is the satisfying story of a servant girl’s cunning, and “The Fairy Pari Banu” features a memorable magic carpet, which has become symbolic of the Nights as a whole. But other tales are humdrum, and “Aladdin” is much worse than that. Robert Irwin, a preeminent scholar of the Nights who contributes a long afterword to the present edition, once called the rags-to-riches story “intrinsically unexciting” and “poorly plotted,” “a pornography of plutocratic excess” with “a brief whiff of anti-Semitism.” The Disney film version, he says—and one has to agree—“is actually less vulgar.” In Horta’s edition, “Aladdin” takes up seventy-one pages; meanwhile, “The Hunchback’s Tale,” one of the glories of prose narrative in any language, is not included at all.

Literary merits aside, Horta also makes a case for Diyab as the most forward-thinking or politically enlightened of the transmitters of the Nights. Whereas the editions of Galland, Lane, and especially Burton are full of racist condescension and misogynistic footnotes, in Diyab’s tales, Horta argues, we find “formidable female protagonists,” as well as “empathy for the underdog and the outsider.” But neither of these claims is convincing. Ingenious women and clever servants feature in many Nights tales, not just those of Diyab, and there are few female characters who can match the princess of “Aladdin” for insipidity. The same whiff of Christian anti-Semitism Irwin finds in “Aladdin,” where a greedy Jewish merchant swindles the protagonist, also arises in Diyab’s memoir, which retells a pair of stories about sneaky or perfidious Jews.

Horta’s edition also downplays the racist and misogynistic episodes in the Arabic stories, seemingly out of the same desire to make them more politically acceptable. In the frame tale, King Shahrayar’s rage is provoked when he witnesses his wife and servant women fornicating with Black slaves in the royal gardens. The queen calls her own lover down from a tree, with the implication that he is somehow simian. In “The Tale of the Enchanted Prince,” a young man also discovers his wife’s infidelity with a Black slave, who abuses her in startling fashion, and the pattern repeats in “The Story of the Three Apples,” although in this case the slave brags about sex that never happened. (The wife is killed anyway.) The motif suggests that the husbands’ violent jealousy is compounded by the race of their wives’ lovers.

In each of these instances, Arabic manuscripts specify “a black slave.” (Burton, typically, calls one “a big slobbering blackamoor with rolling eyes.”) In Horta and Seale’s version, however, each of the adulterous lovers is simply “a slave,” or else is described with a euphemism (e.g., “rough-looking”). Horta includes a brief note connecting the “racist paranoia” of the three tales, but his comment is hard to construe, since the English texts do not mention race. Insulting terms for women are also removed, in a manner that recalls Lane’s averted eyes. In view of these emendations, one wishes Horta had made clear which Arabic manuscripts were the basis of his edition. Given the editorial effort put into the Diyab materials, it is baffling that we are told nothing on this score.

But the real issue isn’t one of faithfulness or accuracy. Editors and transmitters of the Nights, whether in Europe or the Arab world, have always trimmed or padded the texts to suit the sensitivities of their imagined audience. (Haddawy and Mahdi’s insistence on textual fidelity is very much the outlier in this history.) Instead, the problem with such censoring is that it makes it harder to understand the true historical “influence” of the stories.

In Hollywood adaptations of the Nights, for example, beginning with Alexander Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad (1940) and running through Disney’s live-action Aladdin (2019), the genie or “slave of the lamp” is explicitly or implicitly Black. (In Korda’s film, the genie was played by Rex Ingram.) The sentimental love stories are paralleled by equally sentimental narratives of African American liberation: at the end of the animated Aladdin (1992), Robin Williams as the blue-skinned genie exclaims, “Free at last!” (In the 2019 version, the genie is played by Will Smith.) These cartoonish allegories of emancipation fit into a longer history of Nights adaptations, in which the tales’ “Oriental despotism” highlights the political liberties of Europe or America. Censoring the explicit racism of the tales, presumably to make them palatable to a contemporary audience, obscures this history. It is often what is most unpalatable about the stories—and not their up-to-the-minute politics—that ensures their life in the present.

The Annotated Arabian Nights is the latest volume in the Norton and Liveright series inspired by Martin Gardner’s The Annotated Alice (1960). Other titles include The Wizard of Oz, Peter Pan, African American Folktales, and popular novels such as Frankenstein, Huckleberry Finn, and Mrs. Dalloway. Gardner’s edition was the work of a meticulous and passionate hobbyist who acknowledged that there was something obviously “preposterous” about an Alice with footnotes. But Lewis Carroll’s books are full of puzzles, inside jokes, and esoteric references, and Gardner—who kept up a correspondence with Alice-obsessed sleuths all over the world—is a charming and expert guide to Wonderland.

The Nights are not like the Alice books. Many curious things happen in Scheherazade’s stories—she ends each night with the promise of even more astonishing tales to come—but there are relatively few puzzles, obscure words, or literary allusions. The stories themselves solve most of the mysteries they pose, simply through the unfolding of their plots. The great virtue of Seale’s translation is that it never forgets that the most important question—for us as for King Shahrayar—is what will happen next.

Horta’s notes, by contrast, are distractions from the main event. They tell us things we already know, repeat themselves, offer dubious interpretations, or paraphrase what we have just read. When Aladdin is swindled by the Jewish merchant, Horta tells us, “Aladdin is still very naive in the ways of the world and will need to learn more about material values if he is to raise his social status.” Two paragraphs later, when the hero renounces the company of childhood friends, Horta appends another footnote to let us know that “Aladdin’s evolution as a character is becoming clearer. He now avoids his old playmates.”

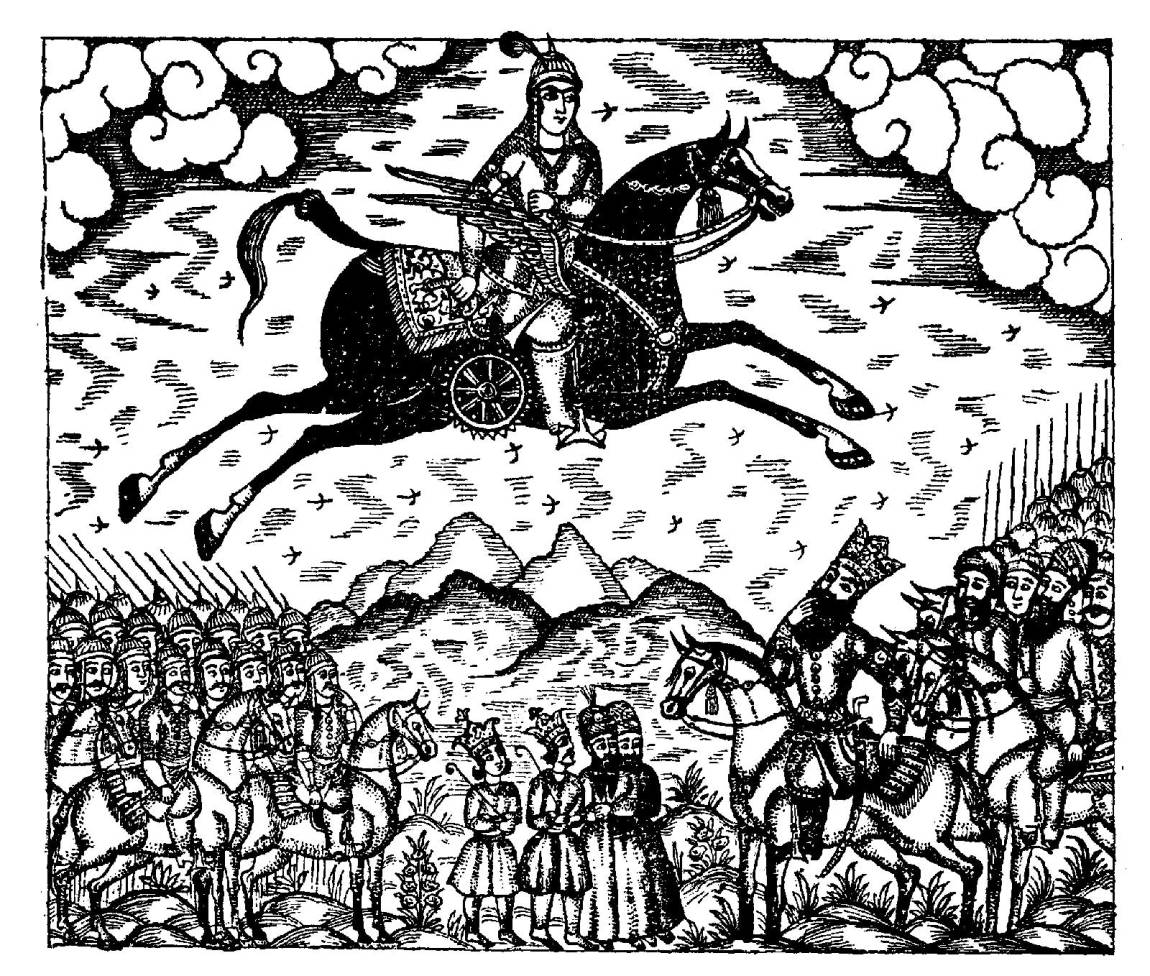

Horta doesn’t seem to trust the stories themselves to hold the reader’s attention. (He doesn’t seem to trust the reader to pay attention at all.) In addition to footnotes, The Annotated Arabian Nights has a foreword by the Egyptian Canadian writer Omar El Akkad, a long introduction by Horta, Irwin’s scholarly afterword, hundreds of color illustrations, an interview with contemporary non-English translators of the Nights, a selection of stories inspired by the tales, and suggestions for further reading. Not all this material is unwelcome; many of the illustrations, in particular, are beautiful. But it is unfortunate that Seale’s elegant versions—the best, to my mind, in English—are embedded in an edition that seems designed to obscure their brilliance. Hers is the voice that will keep us awake at night.

This Issue

November 3, 2022

Gored in the Afternoon

The Illusion of the First Person

Reform or Abolish?

-

1

For more on Galland and his translation, see my “On the Road” in these pages, October 7, 2021. ↩

-

2

Yasmine Seale and Robin Moger, Agitated Air: Poems After Ibn Arabi (Tenement, 2022). ↩