In my cabinet I have a cream-colored soup plate, purchased in the early 1990s at an antique store in Greenwich Village. For me it was rather expensive, despite two chips on the rim, but I had to have it. When I pick it up, the potting feels surprisingly thin: earthenware, fired at a low temperature, weighs much less than a porcelain object of similar size.1 The chips reveal the soft white of the clay body, otherwise covered by a luminous transparent glaze. Six brackets define the profile of the rim, each shaped after an original Chinese form, later filtered through William Hogarth’s “line of beauty”—an S-curve that embodied all that was graceful to his eighteenth-century contemporaries. A hand-painted line in brown enamel continues this restrained prettiness, articulating the outside curves; two thinner lines repeat them and enclose an egg-and-dart pattern. Filling out the lip is a wreath of abstracted leaves and berries joined to a running stem by fine squiggles. Two more lines emphasize the molded edge of the well. The effect is elegant and quintessentially English.

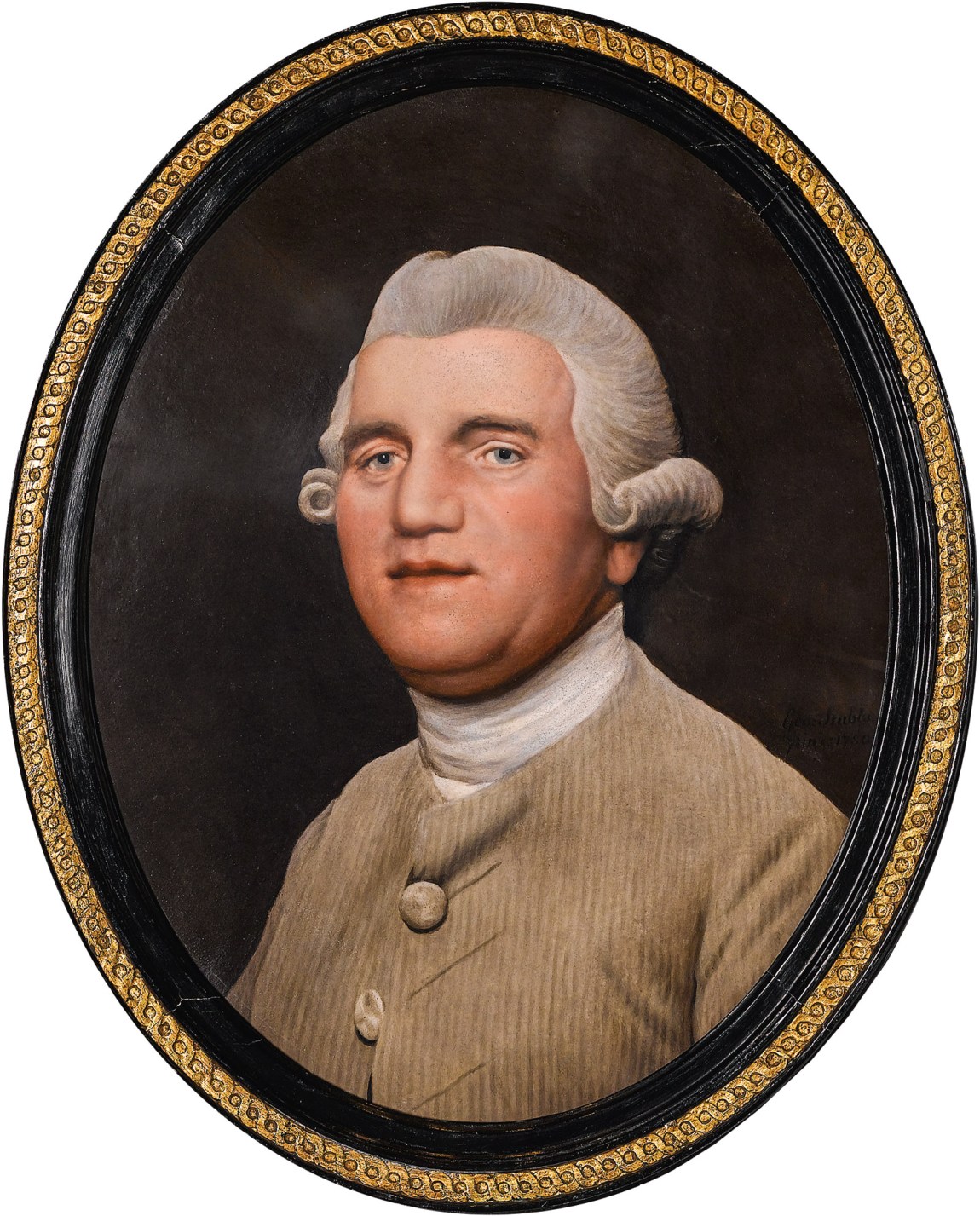

The plate is a slightly damaged remnant from a not very special dining set, but it is one of the most beautiful things I live with. The name WEDGWOOD impressed on the back explains why. It is one of many hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of ceramic objects manufactured under the direction of Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795) at Etruria, his factory in Stoke-on-Trent in the county of Staffordshire in the West Midlands of England. Dinner sets, tea ware, vases, busts, plaques, cameos, and many other useful and purely ornamental items made there were sold across Great Britain, Europe, and the colonial world. Today, ceramics produced at the pottery during Wedgwood’s lifetime are essential elements in any museum collection aspiring to chronicle the development of European decorative arts.

The life of Wedgwood is well documented, thanks to a trove of letters, notebooks, company records, and, most significantly, a voluminous correspondence with his business partner and friend Thomas Bentley. This rich and varied material offers insight into Wedgwood’s artistic, commercial, political, and personal concerns, and touches on some of the most remarkable characters of the time—the botanist, poet, and inventor Erasmus Darwin, the chemist Joseph Priestley, the painter George Stubbs, the diplomat Sir William Hamilton, and even Catherine the Great. As a mass of information, it is both boon and challenge for the biographer, who must organize the overlapping events and accomplishments of a complex life into a cohesive whole.

Considering Wedgwood’s importance in the history of industry, it is appropriate that the historian, politician, and museum director Tristram Hunt would take on his story. Hunt is the author of, among other books, Marx’s General (2010), a biography of Friedrich Engels. The son of a Prussian textile manufacturer from the generation after Wedgwood, Engels worked as a manager in his family’s Manchester factory in order to support Marx during the long gestation of Das Kapital. He famously wrote about terrible conditions in English factories—progeny of the model factory set up by Wedgwood with the intention of improving workers’ lives while increasing quality and efficiency of production. Just as Hunt makes nineteenth-century Barmen and Manchester vivid backdrops for Engels’s life, in The Radical Potter he evokes the Burslem, Liverpool, and London of Wedgwood’s period through exhaustive research and tight descriptive writing. This sense of place also informs another major work by Hunt, Cities of Empire: The British Colonies and the Creation of the Urban World (2014), in which he takes us through ten cities from Boston to New Delhi, portraying dazzling prosperity purchased at the cost of oppression, ending with a crushing description of contemporary Liverpool. His understanding of the origins and consequences of colonialism equips him to assess Wedgwood’s moral and political choices in the face of slavery, revolution, and global commerce.

Most remarkably, Hunt’s own experience touches on recent episodes in the Wedgwood legacy. In 2010, a horrible moment for the regional economy, Hunt was elected as Labour MP for Stoke-on-Trent. When he took his seat, Waterford Wedgwood was insolvent, its new owners trying to profit from viable parts of the enterprise while walking away from its long-term liabilities, including the pensions of thousands of former Wedgwood workers. Under the rules of the UK Pension Protection Fund, the irreplaceable collections of the privately held Wedgwood Museum would have to be sold. Hunt was instrumental in the redoubtable effort to save them for the nation. In 2014 ownership of the museum’s contents was transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum while they remained on view in Stoke-on-Trent. Hunt resigned from Parliament in 2017 to become director of the V&A, where the work of Wedgwood plays a central part in a comprehensive treasure of world ceramics, art, and design.

Advertisement

The status of industrially manufactured goods as art is fraught. When an object is formed by multiple hands working in a factory using specially developed processes and equipment, who is the artist? In the case of Johann Joachim Kaendler, chief modeler for the fabled Meissen porcelain factory in Dresden in the eighteenth century, the answer is obvious. His florid, asymmetrical figure groups as executed by Meissen workers are prime examples of Rococo sculpture, notable for retaining the tender colors of the period in unfading enamels.

With Wedgwood, authorship is less clear. The young John Flaxman was the best-known modeler to work for the company. His designs for Wedgwood are among his most satisfying sculptural works and can be considered the epitome of British Neoclassicism, characterized by references to Greek and Roman antiquities, interpreted with a delicate touch. His masterpiece, the Apotheosis of Homer (1778), also called the Pegasus Vase because of the winged horse making up the finial, was so valued by Wedgwood that he donated an example to the British Museum (see illustration below). Flaxman sculpted the low-relief figural frieze after a print of a red-and-black Greek vase belonging to Sir William Hamilton. The shape, a Piranesian fantasy urn, is not typical of pottery but more commonly executed in stone or bronze. Pegasus rearing above a cloud adds a proto-Romantic touch, his swift movement in marked contrast to the staid relief on the body of the vase. The eclecticism is startling.

What brings these disparate elements together into a coherent and particular visual experience—a work of art—is the clay. A dense, waterproof stoneware invented by Wedgwood, jasperware (“the most delicately whimsical of any substance I ever engag’d with,” he wrote) incorporated ceramic stains such as cobalt blue into the clay body, creating integral color as opposed to applied glazes or enamels on the surface. The vase is potted in the famed “Wedgwood blue” jasper, while the frieze, ornaments, and handles were cast separately in white jasper. Painstakingly applied in a process called sprigging, these flexible “leather hard” pieces were attached to the partially dry vase with a bit of dilute clay, all elements then fusing in the high temperature of the kiln.

Control of the tricky firing was made possible by the thermometer Wedgwood devised to accurately measure kiln heat. His large-scale application of the cameo concept in irresistibly lovely colors—pastel hues of blue, violet, pink, green, and tan—made jasperware a microcosm of the Neoclassical sensibility as expressed in interiors by the architects Robert Adam and James “Athenian” Stuart. Even though an artist as distinguished as Flaxman and a host of other modelers and potters contributed their talents to the immense catalog of wares made by the factory, Wedgwood, by way of his technical and artistic vision, is their acknowledged maker.

His genius, and his central contribution to his own business and ceramic history, lay in the clays and glazes he invented or perfected. As involved as he was with the design process and quality control of his finished wares, the actual shapes, forms, and decorations were primarily the doing of others. But none of it—or the distinguished friends, the royal patronage, the international brand—would have been possible without Wedgwood’s material wit.

Ceramics production requires consistency and uniformity in accordance with a business model that cannot afford excessive waste in the kiln or variations from piece to piece. Formulating a new clay involves sourcing raw materials, preparing them, and combining them in different proportions. Trial pieces are made and fired at different temperatures. Only a tiny proportion of experiments yield promising outcomes. Successful results must be repeated at ever-increasing scale, and compatible glazes and decorating methods have to be perfected. The work is slow, expensive, and often frustrating, conducted at the punishing mercy of the kiln. Wedgwood’s technical notebooks list thousands of such experiments, which occupied months and years of his life.

No wonder, then, that most manufacturing potters use traditional clay formulas. Wedgwood’s family, which had been working the Churchyard Pottery in Burslem for four generations, certainly did. In 1744, when Josiah at age fourteen began his apprenticeship with his brother Thomas, Staffordshire potters had a repertory of red- and buff-colored wares from iron-rich local clays; they also worked with white clays from Devon and Cornwall. These imported materials were the basis for Wedgwood’s first major innovation, his own version of so-called creamware, documented by experiments starting in 1760. He was sure that his improvements to this popular but coarser product could result in resilient, refined, light-colored pottery competitive with the prestigious and much more expensive Chinese and European porcelain that dominated the top end of the market.

Advertisement

Perfecting the creamware body, color, and glaze was Wedgwood’s primary goal once he set up his own factory at the Ivy House Pottery in Burslem in 1759 and four years later in the larger Brick House. It was the work of many years, announced as a new product by 1763, although tweaking continued until at least 1776. The elegant new shapes he created in this new material, with novel decoration—especially the transfer of printed images, which allowed unprecedented levels of detailed ornament at moderate cost—were snatched up by consumers. With his brother John he opened a London showroom, which attracted high-society custom. A tea set ordered on behalf of her royal mistress in 1765 by Deborah Chetwynd, seamstress and laundress to Queen Charlotte, was a breakthrough. Domestically produced earthenware, now in large-scale production, was finally ready for the highest table in Britain. Charlotte appointed Wedgwood Potter to Her Majesty, and creamware was renamed “Queen’s ware.”

In 1760 the Methodist preacher John Wesley sketched the thirty-year-old Wedgwood in his diary:

I met a young man by the name of J. Wedgwood who planted a flower garden adjacent to his pottery. He also has his men wash their hands and faces and change their clothes after working in the clay. He is small and lame but his soul is close to God.2

This is the last glimpse we have of Wedgwood before the texture of the historical record changes from pieced-together inferences to detailed insight provided by the subject himself. From 1762 on we have a lively first-person chronicle of every aspect of his life in many hundreds of letters written to his associate Thomas Bentley until the latter’s death in 1780. The two men were introduced by Dr. Matthew Turner, who attended Wedgwood after he was seriously injured in an accident on the road to Liverpool and struck up a friendship. Turner and Bentley were Nonconformists like Wedgwood, but they had had the benefits of classical learning and travel. They must have recognized exceptional potential in this working potter with limited formal education whose scientific experience was focused primarily on practical outcomes.

In Wedgwood’s letters to Bentley we meet a roaming and curious mind eagerly examining newly discovered fossils and absorbing scientific and literary knowledge from his friends. We follow Wedgwood through the love match with his third cousin Sarah and their happy marriage. Josiah was an anxious, attentive father, carefully supervising the education of his children,3 even running his own school for several years. But for all his loving, genial qualities, the shrewd businessman and the ambitious artist were always present, seeking every opportunity for advancement.

Because few of Bentley’s letters survive, his personality and accomplishments are only revealed through the reflection provided by Wedgwood, yet it suggests a liberal, urbane, and conscientious disposition. Despite being a year younger, Bentley was a mentor to his new friend, offering him a sophisticated worldview edified by travel through France and Italy, knowledge of current taste in art and design, and new horizons in literature, science, and politics. He also sponsored Wedgwood’s entry into the intellectual world of Liverpool, where he was a member of the Philosophical Club and a founder of the nonsectarian Octagon Temple.

Wedgwood constantly wrote to Bentley regarding business concerns, suggesting a more active role for him and allaying his reservations:

The first is “Your total ignorance of the business”—That I deny—You have taste, the best foundation for our intended concern, & which must be our Primum Mobile, for without that all will stand still.

In 1767 they established a formal partnership to produce ornamental wares, separate from everyday goods manufactured under the supervision of Josiah’s cousin “Useful” Thomas. WEDGWOOD & BENTLEY was stamped on vases, with cameos, toilet articles, figures, and reliefs also covered by the agreement; the vases became the height of fashion. Production ramped up in 1769 with the opening of his model factory, Etruria. Worker accommodations included seventy-six ample houses, communal bake ovens, pubs, and a bowling green. The factory was designed so that every task, from making the clay to packing finished wares, could be accomplished in succession without wasted time or risk of damage. Wedgwood supervised production and continued his technical experiments in Staffordshire; Bentley managed the London business.

Both men understood the necessity of aristocratic patronage. Hamilton and other wealthy collectors were sources for antiquities to be copied and potential clientele for new wares. Lady Cathcart, wife of the British ambassador to Russia and sister of Hamilton, promoted Wedgwood and Bentley’s wares in St. Petersburg and Moscow. Her efforts led to commissions from Catherine the Great, including an unprecedented Queen’s ware dinner set for fifty consisting of almost one thousand pieces, each hand-enameled with a different view of the country seats, landscapes, and antiquities of Great Britain.

Bentley’s background made him comfortable dealing with the upper classes, but he had much more in common with Wedgwood. They shared similar values—dissenting religious views, scientific curiosity, a belief in free trade and personal liberty. Their politics were effectively Radical. Early in the correspondence Bentley recommended James Thomson’s 1735 poem Liberty, which criticizes elite corruption and hails Britain as the natural home of political freedom. Stronger fare came with Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and Rousseau’s Émile. Wedgwood expressed sympathy for self-determination by the American colonies, creating a ceramic intaglio, a form commonly used for seals, depicting an impressed image of a rattlesnake coiled under the motto DON’T TREAD ON ME (the motif had been Benjamin Franklin’s idea). He also commemorated the start of the French Revolution with a jasper medallion of the Bastille. “The politicians tell me that as a manufacturer I shall be ruined if France has her liberty,” he wrote Erasmus Darwin in 1789, “but I am willing to take my chance in that respect, nor do I yet see that the happiness of one nation includes in it the misery of its next neighbour.”

The export trade increased. Demand for British ceramics continued in the newly formed United States, and the 1783 Treaties of Versailles opened up French trade by reducing customs duties. Wedgwood lobbied Foreign Secretary Charles James Fox in favor of free trade with France, but in 1785, when William Pitt the Younger proposed open trading with Ireland, Wedgwood strenuously objected, his fear of cheap labor overriding his principles. He even became chair of the General Chamber of the Manufacturers of Great Britain, a protectionist group. The failure of Pitt’s measure ruined Ireland’s prospects for economic growth and destroyed Wedgwood’s Irish market; his goods were boycotted and his agents there had to close their shops.

Wedgwood’s Radical politics were best served when he expressed his opinions through ceramics. Like Bentley and many in their circle, Wedgwood deplored the Atlantic trade in enslaved Africans. Darwin, his close friend and physician, decried slavery in his poem The Botanic Garden, published in 1791:

The SLAVE, in chains, on supplicating knee,

Spreads his wide arms, and lifts his eyes to Thee;

With hunger pale, with wounds and toil oppress’d,

“ARE WE NOT BRETHREN?” sorrow choaks the rest.

Darwin’s written image of the kneeling black man in chains had appeared graphically in 1787 in a woodcut commissioned as a seal for the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Wedgwood, a member of the committee, gave the design to his modelers in Etruria, who produced a white jasper cameo with the delicate low-relief figure molded in black clay and applied to the white ground. Above the figure is the phrase AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER? The tiny oval, about one inch in width, was rendered in a precious material previously only encountered in luxury goods. Wedgwood produced large quantities at his own expense and distributed them widely. Thomas Clarkson, a prominent abolitionist activist, would stop by the London showroom and pick up crates of cameos to distribute at public meetings. Recipients incorporated them into buckles, hairpins, snuffboxes, and other items of personal display. In a letter of thanks for some cameos Wedgwood had sent him, Franklin commented, “I am persuaded it may have an Effect equal to that of the best written pamphlet in procuring favour to those oppressed people.”

To contemporary eyes, this image of a black figure as supplicant is a troubling stereotype. Yet it became iconic in the abolition movements in Britain and the US, generating endless copies in many media. As late as 1835 Patrick Henry Reason, one of the first recorded black engravers in America, reinterpreted Wedgwood’s cameo as a female figure, notable for specific facial characterization and expression.4

Bentley’s death in 1780 was a blow to Wedgwood, who followed Darwin’s advice to console himself by concentrating on “exertion in business, or acquiring of knowledge.” In 1784 he found a project that would preoccupy him for several years. The Portland Vase had caused a sensation when it was unearthed outside Rome in the late sixteenth century. This greatest surviving example of cameo glass was made during the reign of Augustus in a technique perfected by Egyptian artisans. A ten-inch-tall vessel made of deep violet-blue glass was covered with a layer of opaque white glass, which was then carefully carved away to create a frieze of figural decoration with an effect remarkably similar to jasperware. The vase ultimately came into the hands of Hamilton, who sold it to the Dowager Duchess of Portland; Wedgwood borrowed it from her son in order to make a copy. Measuring himself against one of the most famous works of antiquity was an irresistible challenge; his success could be demonstrated by comparison to the original.

The vase has a continuous frieze of figural decoration, now thought to represent the marriage of Peleus and Thetis. Its original amphora form was damaged in antiquity, when a separate cameo glass disk with a profile of Paris was added to the base; squat and awkward, it was “not so elegant as might be made,” said Wedgwood. Nevertheless, after four years of trial and failure he produced about thirty salable ceramic copies as close to the original as possible considering the difference in material.5 It was his crowning technical achievement, its fidelity certified by Sir Joshua Reynolds, president of the Royal Academy, but the work is an anomaly: even though Wedgwood’s other vases derive from previously existing sources, their strong graceful shapes, supported by appropriately subordinated ornaments, are always fresh; as he wrote Darwin, “I only pretend to have attempted to copy the antique forms, but not with absolute servility.” With the Portland Vase he bent the knee. Aligned with some of the most conservative impulses of eighteenth-century visual culture, exemplified in cast collections and painted copies of well-known masterpieces, his replica is artistically disappointing, lacking the invention that makes his other work transcendent.

Within the political culture of late-eighteenth-century Britain, Hunt establishes Wedgwood as a Radical, though his use of the word in his title to modify “potter” is no doubt intentionally ambiguous. For this reader, however, its second likely meaning jars. Peter Voulkos, in the US, was the radical potter of the 1960s. His violent break with the past was stylistic and technical, resulting in new forms and demands for parity with historically privileged media such as painting and sculpture. Today we consider him a great virtuoso, the mantle of radicalism in art having passed to work with pointedly political intentions. In ceramics, Ai Weiwei’s smashing of a Han Dynasty pot and Simone Leigh’s deeply introspective monuments to black feminism carry messages that challenge power and authority. Radical art in our time aims to disrupt.

Such disruption in the form of an art object would have been alien to Wedgwood, though his new clays changed ceramics forever. The objects he produced surprised and delighted his contemporaries and were immediately assimilated into their larger material culture, without disruption. There is nothing radical about the magnificent pots that transfix us at the V&A in London and Stoke-on-Trent, or the Beeson Collection at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama. Like all ceramics, they radiate warmth from the touch of the hands that made them, transformed by the fire of the kiln. Wedgwood’s lasting testament was his aspirational vision of what ceramics could be—embodied even in the simplest soup plate.

-

1

Earthenware is lightweight and porous; common examples are utilitarian objects such as terra-cotta flowerpots. Stoneware is high-fired, waterproof, and opaque, often used for everyday vessels like jugs and beer steins. Porcelain, invented in China, has the highest firing temperature, becoming the vitreous, impervious, and translucent ceramic body found in fine service and decorative wares. Factory-made wares are usually fired multiple times. The first firing transforms the clay form into a hard ceramic body. The object is then dipped into a liquid glaze that is fired again to give a shiny, protective coating. Decorations such as enamel painting, gilding, and decals are subjected to a third firing in a low-temperature kiln. ↩

-

2

Wedgwood’s right leg was weakened by smallpox when he was an apprentice, leaving him unable to operate the potter’s wheel; eventually his leg was amputated. ↩

-

3

Six survived. His daughter Susannah married Erasmus Darwin’s son and became the mother of Charles Darwin. Charles married Wedgwood’s granddaughter Emma. ↩

-

4

Illustrated on Reason’s Wikipedia page; Reason will be discussed in a forthcoming book about images of abolition by Phillip Troutman. ↩

-

5

The replica was exhibited to great acclaim in the London showrooms and a special viewing arranged for Queen Charlotte. Wedgwood’s heirs continued to produce the Portland Vase in the nineteenth century. It became so identified with the company that a tiny image was used as a backstamp on many wares starting around 1878. ↩