In 1962 the artist Robert Morris made a sculpture called I-Box. It was about the size of a large book, with a capital “I” incised into the front surface and hinged like a cupboard door. When opened, the I-shaped portal revealed a black-and-white photograph of the artist facing the viewer wearing only a sly grin. This was before Morris embarked on a strenuous program to sculpt his body, which he then showed off in an infamous 1974 gallery announcement of himself posed as a bicep-bulging neo-Nazi leather boy, a photo that inspired an even more infamous photograph in Artforum of the very buff (and in the buff) Lynda Benglis making sport with a large dildo. But I digress.

Some twenty years later, the artist Charles Ray, recently the subject of a major exhibition at the Met (along with simultaneous shows in Paris at the Bourse de Commerce and the Pompidou), made a work that harked back to Morris’s I am my own artwork spirit and combined it with the soon to be familiar format of utilitarian objects arrayed on a shelf. The selection and display of things had replaced, for a time in the early 1980s, the more labor-intensive making of things. Ray merged the interest in presentation with performance, completing or extending a constructed form by inserting his own body.

In his Shelf (1981), a gray metal shelf supporting a metal toolbox and some other junk is attached to the wall at neck height with a circular cutout, so that the artist’s head, as he stands against the wall, appears to rest on the shelf. Ray’s head is painted the same gray color as the industrial products, while his naked body below the neck remains unpainted. The expression on Ray’s face is one of grim resolve, like a cadet at attention. With a pinch of subversion, Shelf literalizes an old idea, the separation of mind from body, and a more recent one, the commodification of the artist. It’s also a joke, or an object lesson, about the lengths to which one must go to make art—all the way to self-decapitation. One thing is clear: this guy will do anything for his art.

An artist’s sensibility is often a blend of influences that may seem on the surface to have little in common. A major artist inevitably gathers up in himself quite diverse currents of thought and style. Think of Jackson Pollock, whose work combined the regionalism of Thomas Hart Benton with aspects of Navajo sand painting, Surrealist automatism, Picasso’s linear fragmentations, and the compositional dynamism of the sixteenth-century Venetian masters. Sometimes young artists can’t easily find one container for all their ideas and longings, one that also allows them to show off their understanding of the complexity of their historical moment. Those artists need to percolate longer.

Ray came of age in the late 1970s, after the formal rigors of postminimalism had split in two directions: the idiosyncratic, poetic charm of arte povera and the self-interrogation and intellectualism of late conceptual art. Whatever one’s talents or inclinations, ideas about materiality, the natural world, the uses of representation, feminism, and art’s relationship to the broader culture were making their way through the art world as the 1970s gave way to the 1980s. The one idea shared by these scattered trajectories was the efficacy of intention: that what an artist intended would, through an act of aesthetic transference, determine a work’s form, with or without the active involvement of the artist’s hand. This belief in the power of thinking to shape, literally, a work’s meaning and its reception in the world is fundamental to the art of our time. It’s the aesthetic equivalent of orienting your stance in the direction you want the golf ball to travel. Sometimes it works, and other times not so much.

The exemplary artist of that period was Bruce Nauman, who had (and still has) the uncanny ability to upload complex, inchoate, often uncomfortable or otherwise hard-to-access states of mind into simple sculptural forms or mise-en-scènes without appearing to do very much at all. In a seeming paradox, Nauman made obscurantism vivid and inscrutability erotic. Many other consequential artists also flourished in the mid-to-late 1970s; there was a lot of interesting art, but not much in the way of objects or permanence. Few artists were in the masterpiece business. It was a time of keep it simple, travel light, and don’t expect to be understood. In 1981, barely two years out of grad school, Ray was hired to teach in the sculpture program at UCLA’s School of Art. It was fortune calling; the perpetually emergent Los Angeles scene offered just the right ratio of attention to autonomy.

Advertisement

Ray started out as a maker of actions rather than of things, but soon props overtook gestures. The earliest works in the Met exhibition are photographs of sculptures made with the artist’s own body. Plank piece I and II (1973) show him precariously pinned against the wall by a hefty wood plank that looks about eight feet long. In Plank piece I, Ray is draped over the plank bent at the waist, while Plank piece II has him pinned upside down, bent at the knees.

These pieces are comic/desperate restatements of what had become avant-garde conventions: the artist using his own body as material and sculptures that use gravity to determine form, prime examples of which are Richard Serra’s Prop pieces of the late 1960s, in which sheets of steel or lead are pinned against the wall solely by the force and angle of a lead pole. Other early Ray works, like the tongue-in-cheek open-top box of milled aluminum, 81 x 83 x 85 = 86 x 83 x 85 (1989), which looks like a replica of a Donald Judd, have a similar mix of the earnestly self-evident and the ludicrous.

Ray’s art represents the intersection of conceptual art (itself a tributary of formalism’s self-referential, art-for-art’s-sake impulse) and classicism, a kind of tightly controlled and codified realism. One emphasizes intention and the other surface: the ideational versus the external world of appearances. And while the two approaches might once have seemed irreconcilable, they share one defining trait: a literalness that extends to process as well as result. An idea, once set in motion, becomes a road with no offramp. In the conceptual playbook, every prophecy must be fulfilled, and extremes of endurance or budget correlate to serious intent. The look on Ray’s painted face in Shelf signifies a commitment to stay the course, to see the inconvenient project through. The artist disappears inside the decision to do something, hopefully reemerging on the other side, like a Buster Keaton gag: whatever near-fatal calamity is set in motion, we’re left with Keaton’s doleful countenance at the end.

A young artist may use his own body out of conceptualism’s permissions, and also because, in a way, it’s all he has. By the end of the 1980s Ray was ready for something more outward-looking. Just how he evolved from the demonstrative/documentary mode, casual in appearance, to making exacting replicas of things found in nature, is a little hazy, but by 1990 Ray had embarked on a series of works that employed meticulously detailed and painted fiberglass mannequins, largely constructed by professional model makers, coiffed and clothed (when applicable), and often staged in provocative poses.

These pieces from the early 1990s—like Fall ’91 (1992), an eight-foot-tall woman in a power suit; Family romance (1993), four naked members of a nuclear family; or the self-mocking Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley… (1992)—cemented Ray’s reputation. But although every ounce of skill was focused on creating a humanlike presence of striking verisimilitude, with hair and eyelashes and clothes all painstakingly replicated, these works are portraits of mannequins, not of actual people, even when the model—as in the case of Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley…—is recognizable. Call them people-adjacent. This adjacency itself had a seductive power; the precise distance between the human and the simulacrum became a kind of aesthetic principle, a signifier of attitude, and of risk.

This work coincided with a new sensibility that eschewed the artist’s hand. The idea was to use technology to be more machinelike than even Warhol could have imagined. Exacting replication as an approach to making art answered a lot of formal questions. What should it look like? Whatever the original looks like. Where figuration had previously involved some interpretive element, now all one needed was fidelity to the model. Seemingly overnight the perfectibility of commercial fabrication became something that couldn’t be argued with.

The look of machine-assisted realism that marked the new figurative sculpture helped to shield these artists from the kind of critical resistance that dogged the “return to figuration” in painting in the 1980s. That work was often accompanied by looser, more gestural brushwork, which amounted to high-brow apostasy. It’s the nature of the medium, or one of the natures, anyway: even paintings with a high degree of finish still retain a sense of one maker and one immediate experience.

Making sculpture, however, is often a much longer, collaborative process, involving technicians, foundries, a fat checkbook, and, not least, managerial skills. The new figuration in sculpture, coming as it did not from the traditional studio practice of modeling or carving, but rather from industrial techniques and a fascination with replication and surrogacy, seized on the new possibilities of an exacting three-dimensional verisimilitude, which always seems to awe the viewer, or, as Benjamin Franklin might have put it, “to make the mob gape and stare.”

Advertisement

This all happened very fast, and the scale of the change is a little hard to get your head around. Imagine the surprise of someone who fell into a coma in 1980, when artists like Serra, Robert Grosvenor, and Mark di Suvero represented high points of modernist sculptural achievement, and awoke a mere ten years later to find museums and galleries filled with objects of a highly detailed realism. It was almost as if the previous fifty years in sculpture had never happened.

As the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, Ray was one of a handful of artists—Matthew Barney was another—who used figurative sculpture to express a new kind of non-nostalgic estrangement, one that was tied up with a desire to transcend the limits of the merely human. This trend was called “posthuman”; it was largely a literary sensibility and had at its core a sympathy for the futurology of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and the novels of J.G. Ballard as metaphors for our almost cellular discontent, and our boredom. The future was now. The paradox of this new emotionality is that it is both thrill-seeking and muted, both hot and cold: hot images, cold affect.

Two of Ray’s works in particular, both mordantly funny and transgressive, were endlessly reproduced in the art press and prominently featured in important group exhibitions; they further established him as “the guy who will do anything for art.” Absent from the Met show but included in the catalog is Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley…, a group of eight life-size, highly realistic male nudes made of painted fiberglass, all of which have Ray’s body, face, and hair and are posed in a kind of orgiastic daisy chain. One figure grasps another’s ankles, one kneels before another’s crotch, while another addresses himself to the ass of a fifth, etc. Interestingly, while there is arousal, no actual penetration is depicted; it’s coitus interruptus in perpetuity.

In the years since it was first exhibited, Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley… has shed some of its original shock, and it’s now possible to see the tenderness, even fragility alongside the satire of male desire. If anything the work has become Ray’s ars poetica, the masturbatory, tell-any-secret aspect submerged into a faux-bland visage. The effect changes as the viewing distance increases. Seeing Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley… or Family romance today, on the page or across a large room, the figures seem smaller than in memory, more in need of rescue. To experience again that frisson of the uncanny, one now has to see the figures close up, to look into the expressionless eyes and marvel at the excruciating exactitude, the details that add up to a kind of pasteurized death mask. Is all figurative sculpture on some level funereal?

Family romance, the other seminal work from that time, was included in the Met show. It features two parents, male and female, and two prepubescent children, boy and girl, all unclothed, standing in a straight line holding hands, as if in an ad for a nudist family resort. Here we are at the lake! Everything about it is off. Though executed with fiberglass exactitude, the adults’ bodies are compressed to the same height as the children, and the kids have been stretched through the torso to further equalize the difference in height. Parents shrunk, kids stretched—that’s one depiction of a modern American family. The figures appear real and impossible at the same time. Everything is out of proportion, and yet we accept them, sort of, as plausible. Who are these people and what are they doing here? Are they the latest development in human evolution? Is this what it’s come to? Looking at these two works, and others in which the subjects appear naked, is like the sensation of being caught unawares by a camera flash—everyone feels overexposed in the scalding light.

The figures have no answers—they just are; the family in a modern circle of hell. They are caught in a passive-aggressive drama of exposure and discomfort, the wigs a bit wonky, the expressions troubling. The staging of the figures is decisive. Holding hands is an active pose; it emphasizes their claim on one another, their desperate powerlessness. The parents look as though they’ve now thought better of the idea to pose like this—What have we done?—but it’s too late. They have to grin and bear it, while the kids, especially the girl, look put upon, pissed off.

See? I’m identifying with the figures as people, devising little scenarios for them. It is this dynamic, the impulse to project our thoughts into the minds of others, that animates figurative sculpture generally, but now it hurts. However, take a step back, blink, and the figures are objects on a shelf. Industrial products, people—what’s the difference, exactly? Are these hybrids a disappointment on behalf of humanity, or are they new toys? This is work that appears mute as you approach it, but as you turn and walk away a whisper can be heard: “Help me; love me.”

Ray has talked about wanting to make a contemporary kouros, but his work has little of the forward motion depicted in a Greek original. His people are simply rooted to the floor and, with some exceptions, are missing that sense of outward-projecting life force. Perhaps conversely, what they do aspire to, like the Tin Man, is an inner life, a heart.

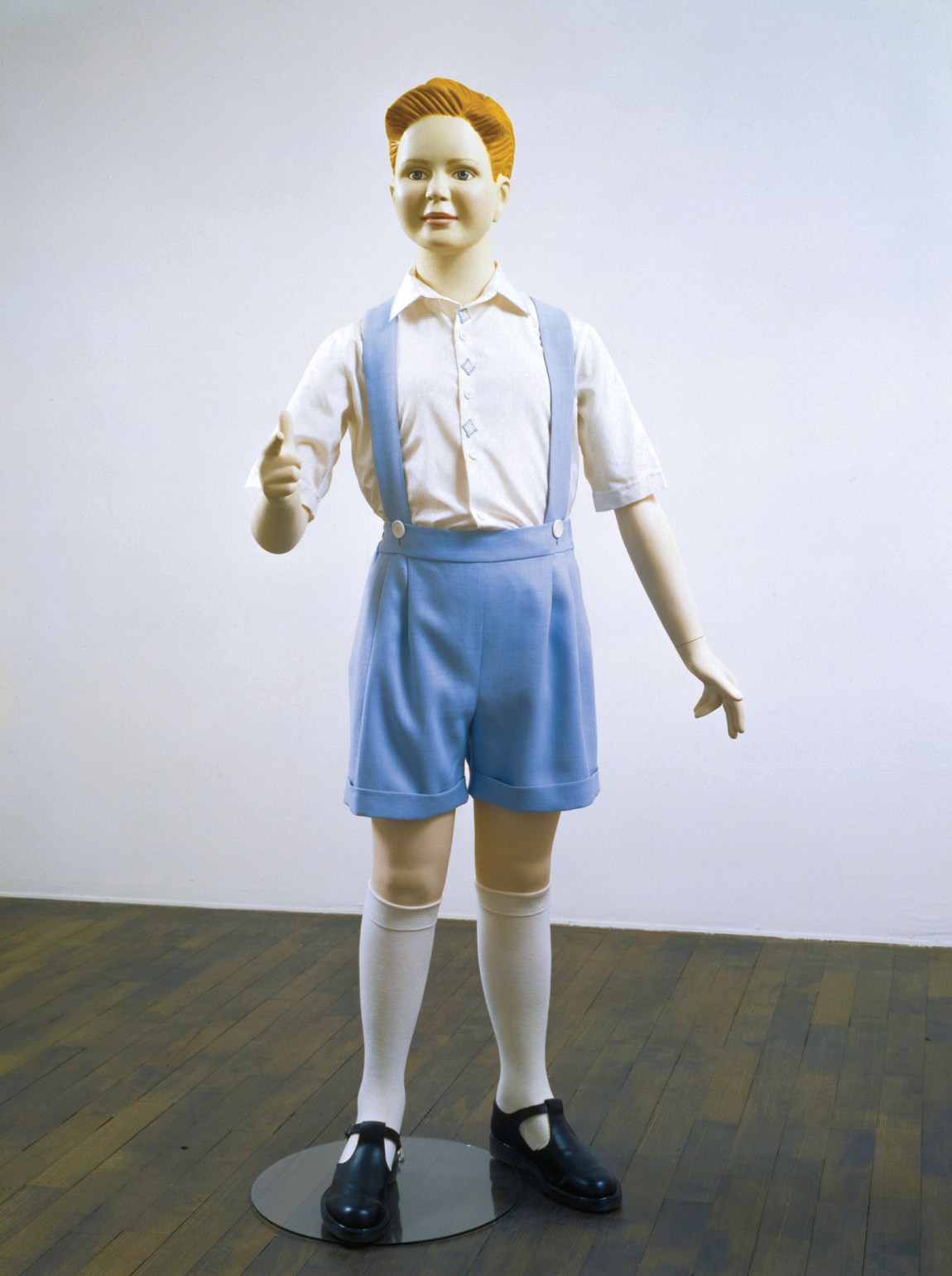

Boy (1992) is a larger-than-life-size painted fiberglass mannequin of a sturdy yet strangely effeminate young boy, with overfull cheeks and a faint smile on a blank, blond face (see illustration on the right). As much as Ray seems, like the Greeks before him, to celebrate the unclothed body, he also takes great care with period garments when appropriate. The boy is dressed in white shirt, powder blue shorts and suspenders, knee socks, and black shoes, the kind of outfit that overprotected grammar school boys would have worn in the 1940s and 1950s. He looks a little dusty, like a store-window display in a provincial downtown at midcentury. Here Ray exploits to full effect his primary aesthetic tool: scale. Things that are too big or too small undermine our sense of spatial logic; they seem to challenge the spaces that we occupy. You come up close to the boy, perhaps to pinch his cheek or ruffle his hair, but realize that he’s taller than he should be, at just under six feet, perhaps taller than you, and he actually looks not so nice; maybe better to keep your distance.

Ray also seems to take an interest, almost certainly ironic, but then again maybe not, in showing off his own wardrobe. Two pieces in this vein were not at the Met. Self-portrait (1990) is a mannequin of the artist dressed in what the catalog calls “his favorite sailing outfit”—a very ordinary windbreaker and bucket hat, the embodiment of everyman unexceptionalism, goofy, and so straight as to signal that something is off. One piece that made me laugh out loud, Puzzle bottle (1995), features a miniature figure of the artist, somewhat roughly carved and painted, standing inside a clear glass jug. At about a foot tall, the tiny artist wears jeans and a green shirt with too-long sleeves; he sports oversized glasses and peers out at us with a befuddled “How did I get here?” look on his face: dweeb in a bottle.

What a strange thing is man. Ray’s own image—his head and body, clothed and nude, alone or in multiples, standing, leaning, or on horseback, and also inserted into geometric, body-bisecting forms—appears in so many of his works that it’s as if he’s trying to get a sense of what he looks like, a questioning that reaches down even to the amount of space he occupies. His sculptures ask not just “Who am I?” but “What am I?” Making himself the subject renders the work irrefutable in a way, a strategy partly derived from a strain of conceptualism in which the artist is his own test tube, a conceit to which Ray adds a mountain of sheer will.

Around 2000 Ray shifted from polychrome fiberglass mannequins with meticulous surface details—clothing, eye color, etc.—to using 3D digital scans and other technology to make unpainted figures cast and carved from metal and wood. Whereas the mannequins had been funny, alarming, or provocative, the works in metal are stately and reserved, almost elegiac. They are clearly modeled on specific people chosen as representative types rather than distortions of commercial imagery, with an accompanying shift in tone to a more mature gravitas.

Two such pieces in the Met exhibition that I think are particularly successful have a rich literary provenance. The polished stainless-steel Huck and Jim (2014) represents a moment in Huckleberry Finn when Huck and the escaped slave Jim debate the origin of the stars while floating down the river on their raft. Ray has imagined the scene interestingly: Huck and Jim are both naked. Huck, confident and at home in the world, bends down to scoop up something from the water, while Jim stands upright beside and a little behind him, with his right hand extended, reaching almost to Huck’s back but without touching him. The gesture is cautionary, protective. Jim, at just over nine feet tall, with a handsome, open face, muscular body, and excellent posture, is close up and intimate, yet reserved. Huck is oblivious to anyone who may be watching, while Jim is clearly aware of a world outside of himself. It’s a powerful work, hushed within its contained strength, and gathers up so much—literary, historical, theatrical—into the two figures and their shared space.

Sarah Williams (2021) recreates in larger-than-life-size stainless steel the scene in the novel where Huck dresses up as a girl so as to slip into town incognito to glean what’s been going on since he and Jim set out on the raft. He stands before us as if in a ritual, transformed into Sarah, wearing a full-length, high-waisted dress, his head slightly bowed, his eyes closed. Jim, dressed in his everyday clothes, kneels just behind Huck with his gaze on the row of hooks that run along the back of the dress. He has just finished fastening the hooks, and his hands are resting on his thighs, his head tilted to one side as he considers his work with a pensive expression. The models for Huck and Jim are different here: Jim has a shaved head, and Huck appears to be a young boy, which of course he is.

The work has an attitude of stillness on the edge of portent; it’s almost unbearably tender and poignant. The positioning of the two figures, the directions of their respective gazes, the body language—it’s all just right. The way the metal has been worked to represent the folds of cloth and the crease of shoe leather is especially effective: it shows the mature artist that Ray has become. These works are overtly theatrical; Ray imagines what a scene from literature (or mythology) would look like and then executes it in a fairly straightforward, even literal way. But the literal in this case is first of all an act of imagination. One of Ray’s strengths, along with his command of scale, is the eloquence of the spacing between his figures. He deftly controls the tension between them the way a theater director might. Meaning is also a matter of staging, of nearness or farness, varying heights, the space underneath an extended arm, or the arc of an enfolded body as it bends forward to pick up something on the ground.

A third work, Archangel (2021), has some of the same synthesis of image with narrative (see illustration at beginning of article). Here is the archangel Gabriel in the guise of a lean young surfer dude, one and a half times life-size, shirtless, long hair in a man bun, jeans rolled up, just the right amount of definition in the muscles along the arms and back, with a long, straight nose and full lips—an altogether beautiful young man. We see Gabriel at the instant he alights on earth, one foot touching the ground, the other heel still extended high in the air. The figure is carved from blocks of hinoki cypress with a combination of strength and delicacy.

Ray poses his Gabriel on a high pedestal, which makes him over thirteen feet tall, towering over the viewer, with his right arm raised behind him and his left arm extended in front, the hand cupped as if around an invisible glass, a pose familiar from centuries of European painting. The surface of the hinoki wood looks sensuous and taut, and the level of detail that Ray’s Japanese wood-carvers were able to coax from it is astonishing without becoming the entire point of the piece. Gabriel’s feet, at just below eye level, are shod in flip-flops, with their sinews and tendons visible beneath the smooth wood “skin,” and the stitching and creases and fly button of the jeans are marvels of attained form. The work has grace and power; it’s as close as Ray comes to a baroque expressivity. There is also a tantalizing overtone of collapsed time, of giving a mythological dimension to the everyday. Choosing to embody Gabriel as a modern-day youth is a nice touch, not unlike Raphael putting the face of his mistress on a painting of the Madonna.

Two other works that were in the exhibition don’t encourage the level of emotional involvement that comes easily with the Jim and Huck pieces, though they are both well thought out and executed with great skill. The polished stainless-steel Reclining woman (2018) is a finely detailed recumbent nude woman, somewhat larger than life-size, propped up on one elbow in an odalisque pose, one hand draped over a thigh, the opposite knee slightly bent, atop a massive rectangular base. The figure is in early middle age, neither lithe nor idealized, thickened a bit around the middle, with ample haunches and cascading hair—in other words, based on a real person, animated as if in life but stilled forever, like a tomb ornament for someone’s mom.

Who is she and how did she get here, and why are we looking at her? Unlike Manet’s famous Olympia, who meets the viewer’s gaze, this woman is looking slightly down and away. Yet there is some ambiguity about her degree of complicity; insofar as a pose and tilt of the head, mass of the body, etc., indicates anything, “she” appears to be aware of it all, to take in the exposure as part of her contract with the sculpture. A wall label informed us that the model for the work is the manager of Ray’s bank. I’m not sure what that information adds to the sculpture—I was tempted to ask her to look up my balance—but people love a good anecdote, and it does establish that Ray is connected to the quotidian world in the way of the artist, seeing things that others miss. But unlike marble or wood, the metallic surface doesn’t absorb our gaze, which is literally reflected back; our eyes roam around the surface contours struggling to obtain purchase on the overall mass and form.

There is something mildly unsatisfying about our relationship to all that metal—classical art in search of an allegory. It’s meant to represent the endlessly strange facticity, the wonder even, of an up-close encounter with another human being—and the unknowability, despite the exposure, of another’s body from the inside. The effect in this case may be thrown off by the base: it’s either too big or too small in relation to the figure, or too uninflected, the modernist convention of non-adornment at odds with what the complexity of the piece is asking for. The reclining woman, with her handsome Roman nose and enviable wavy hair, in her overall solidity and rootedness and also inaccessibility, wants to be a modern-day sphinx, but one without a riddle.

Mime (2014) is a life-size aluminum figure of a man wearing a long-sleeved shirt and trousers with suspenders, lying on his back on a low cot, one arm over his forehead, the opposite leg cocked 90 degrees at the knee. We are informed that the model is a famous French mime, which I guess is kind of interesting, and certain details of the cot—the wooden supports, the canvas sling—may or may not be a reference to painting, weighed down as it is by the mime’s body. I find the work rather maddeningly lifeless, swamped by its Greco-Roman forebears hovering above in the mental air. Another version of the work was made a year later of cypress rather than metal (I have not seen it, but it’s reproduced in the catalog), and it seems to work better.

What does “better” mean in this context? The difficulty with realistic figures cast or carved from metal resides in the “inside” creases—like the place where the head makes contact with the canvas cot, or the way the metal “fabric” of the sleeve pulls away from it. These particularities have to be emphasized with hand tools after the industrial knives have done their job, and the uniformity of the metallic surface is always in danger of puddling up and losing the separation of surface forms. Wood has no such problem—it is more easily gouged, carved, incised, etc., so more readily conveys the compressed strength of the image as it emerges out of the material.

When an artist’s style is rooted in verisimilitude, when mimesis is both the starting point and endpoint, when fidelity to surface anatomy dictates the path the eye must take, with little or no leavening of the relentless realism, I sometimes have the feeling of being in an elevator when it falls a few floors before coming to an abrupt stop. Your stomach lurches with it. This is one of the problems facing figurative sculpture today: the slavish replication of what is can feel overdetermined and airless.

It’s certainly not a new idea to merge mimesis with transference. Walter Benjamin defines mimesis as “non-sensuous similarity.” As we look down at the recumbent mime’s face in the Met’s version, the features merged with the metal’s reflective surfaces, it’s hard to locate the person in the work. Of course, mimes are mute by definition and are often annoying, perhaps deliberately, but something about the sculpture feels not only mute but out of reach. Yet it has elicited extravagant praise from critics and has been portrayed in the art press as a tightening of an aesthetic screw: all of its component parts—intention, form, material, execution—in a perfect, vertically layered synecdoche.

Mime invites meditation on the theme of who gets to speak, and one of Ray’s gifts seems to be positioning his work in just such a way as to elicit a sustained interpretive echo. I do not say it lightly or without admiration. This is a real skill, and Ray knows as well as anyone that the art world runs on the inversion principle: cool, dry art = hot, wet narrative. For me the way the work emerges out of its themes is a bit like time-lapse photography, only not quite completed, like a flower bud that fails to open. The mime re-submerges into its classical models. I think Ray might be at a crossroads. For some time he has been our poet of stasis, stoicism, and entropy. He seems to want to be bigger than that now, to trade hermeticism for a more sweeping narrative, literary valence. I hope he does.

The Met exhibition was beautifully installed—spare, well spaced, and expertly lit. Nineteen works occupied two large, high-ceilinged rooms, and almost all of them were sober and serious. Some of Ray’s greatest hits were there, and it was a complicated pleasure to see them again. A few have achieved such notoriety over the last twenty years that they are inevitably a bit of a letdown in person. A few are muffled or inert. One such head-scratcher is Tractor (2005), a full-size aluminum replica of a partially opened-up tractor that Ray found abandoned in a field somewhere. The first impression is like coming upon a patient on an operating table. The whole thing has been remade: the machine was completely disassembled and every part cast or carved or otherwise fabricated from aluminum, and then put back together again.

Consider what that means in terms of man-hours: making a cast of and then casting in aluminum a replica of a part you could buy at any Pep Boys. My assistant, who will drive miles out of her way to visit a tractor museum, thinks it’s the greatest single artwork ever made. I can just about imagine the impulse without having a desire to replicate the experiment myself. It’s Frankenstein’s monster, a golem, a memorial to industrial entropy, and a testament to the staying power of conceptual art all in one. The work reminds me of something John Baldessari was fond of saying: “This is the way we make art now.” The closed system, the non-deviation, life as I found it. Maybe that’s why critics like it so much—even if it’s stuffy, the room is familiar.

Ray is like Zeno at the mall, never quite arriving at his destination. Everyday happenings stretch on for miles, as looking and attention become atomized and hybridized in the digital age. Tractor is the work of someone who believes he can only know something by remaking it on the industrial equivalent of a cellular level. In so doing he reaches the limits of appearance—we can’t go beyond what things look like. I suspect that for certain segments of the audience, the disproportion between effort expended and result is a large measure of the awe that the piece inspires. Call it the Ray effect: he’s all in. Of course, every good artist is all in, but seldom does one’s all-in-ness necessitate years of labor to produce a single work. It’s a tractor, not the Sistine Chapel.

The exhibition catalog contains useful essays by the show’s two main curators, Kelly Baum and Brinda Kumar, and a lively conversation between Ray and the critic Hal Foster that shows off the artist’s intelligence and sense of humor. At one point Foster asks Ray a question about his practice, and he answers, “I don’t see sculpture as a ‘practice’—I’m almost allergic to that word. My dentist has a practice; I have a behavior.” When asked about his level of awareness in regard to the loaded content of the Huck and Jim figures, Ray replies with equanimity: “For me it is simply best to say that the artist is responsible for what he or she makes. I wasn’t naive about the power of the nude images of Huck and Jim.” I think that’s right. Artists needn’t have a completely worked-out interpretive model, something they can explain at the drop of a hat, to know when they have struck a rich lode of meaning and feeling.

As artists we are always trying to insert a metaphorical bridge between thinking, seeing, and feeling—between the viewer, the cultural setting, and the embodied object or action. Ray’s art asks some fundamental questions about our human condition: Can I bear being a person? Knowing anything about another’s state of mind or inner life requires an imaginative projection—without it there is only surface. Ray seems to want to imbue his figures, just as earlier artists might, with something like a soul. But as a good modernist, he is steeped in the very impossibility of that project, at which point we are redirected to what can strictly be known by the senses.

Mime, and also to a certain extent Reclining woman, are deliberately mute, but one senses that Ray doesn’t want them to stay mute, only to represent muteness or unknowability. He seems to want to get inside of his subjects, to pour himself into them, like the molten aluminum of which they are made, but then thinks better of it, as he knows it’s a philosophical impossibility. The paradox of art, or representational art anyway, is that the artist is confined to the surfaces of things; we can only know the inside by looking at the outside. And it’s the work of the sculpture to ignite our desire to pierce its daunting metallic skin, even though we know we can’t.

I have tried to project myself into the animating impulse behind Ray’s art, and I’ve found it difficult at times to align with its source. Ray is everywhere and nowhere. Just when I think I’m getting closer, the work seems to spread out or dissolve before me. Ray is inserting himself into the mechanisms of representation, of exchange value and context, of making something to stand for something larger—a common enough ambition, and a high one, but somehow in Ray’s version I keep coming up against an alternating current of wished-for transparency and stubborn opacity. In any case, I’m in a distinct minority here; he enjoys a level of acclaim accorded very few living artists. Ray is the perfect institutional artist; his work is overweeningly ambitious, technologically sophisticated, and yet restrained in appearance, and it allows the audience to enjoy figurative realism without the taint of kitsch.

I suppose this is another way of saying that Charles Ray, by himself, for all of his probity and self-seriousness, for all the depth of his consideration of the aesthetic and cultural issues involved in his work, comes off as a bit stuck. You can only hold your breath for so long. Finally his work exists within a narrow vibrational range. Part of me wants Rauschenberg, who was so full of love, to come along and put a tire around something, although of course it’s wrong to want art to be other than what it is. This is classical, figurative art with the eccentricity baked in and the perversion burned off.