Bob Dylan’s new book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, is a kind of music-appreciation course open to auditors and members of the general public. It is best savored one chapter, one song, at a time, while listening to the accompanying playlists, which its readers have assembled on music-streaming platforms. Professor Dylan lectures a little, then you press play.

My friends and I used to frequent this sort of course in college: Listening at Noon, taught by a beloved emeritus professor of music, Henry Mishkin. Besides us, the other students were all retirees. Mishkin would cue up a record of, say, an aria from Verdi’s Nabucco, wait patiently for the beauty to kick in, then enter a trance state, moving his compact, elderly body along the contours of the soprano’s song. We were part of a generation not yet named, Generation X, surrounded by people born around the turn of the twentieth century. Here was the tail end of something; one man listened through an ear trumpet, as though it were an evening in 1841 at La Scala. If Nabucco, or Mishkin, was going to be remembered, it was up to us to carry the torch. This mattered to us: we were nice young people, not at all rude or spiteful the way Dylan and his generation had been when they were our age.

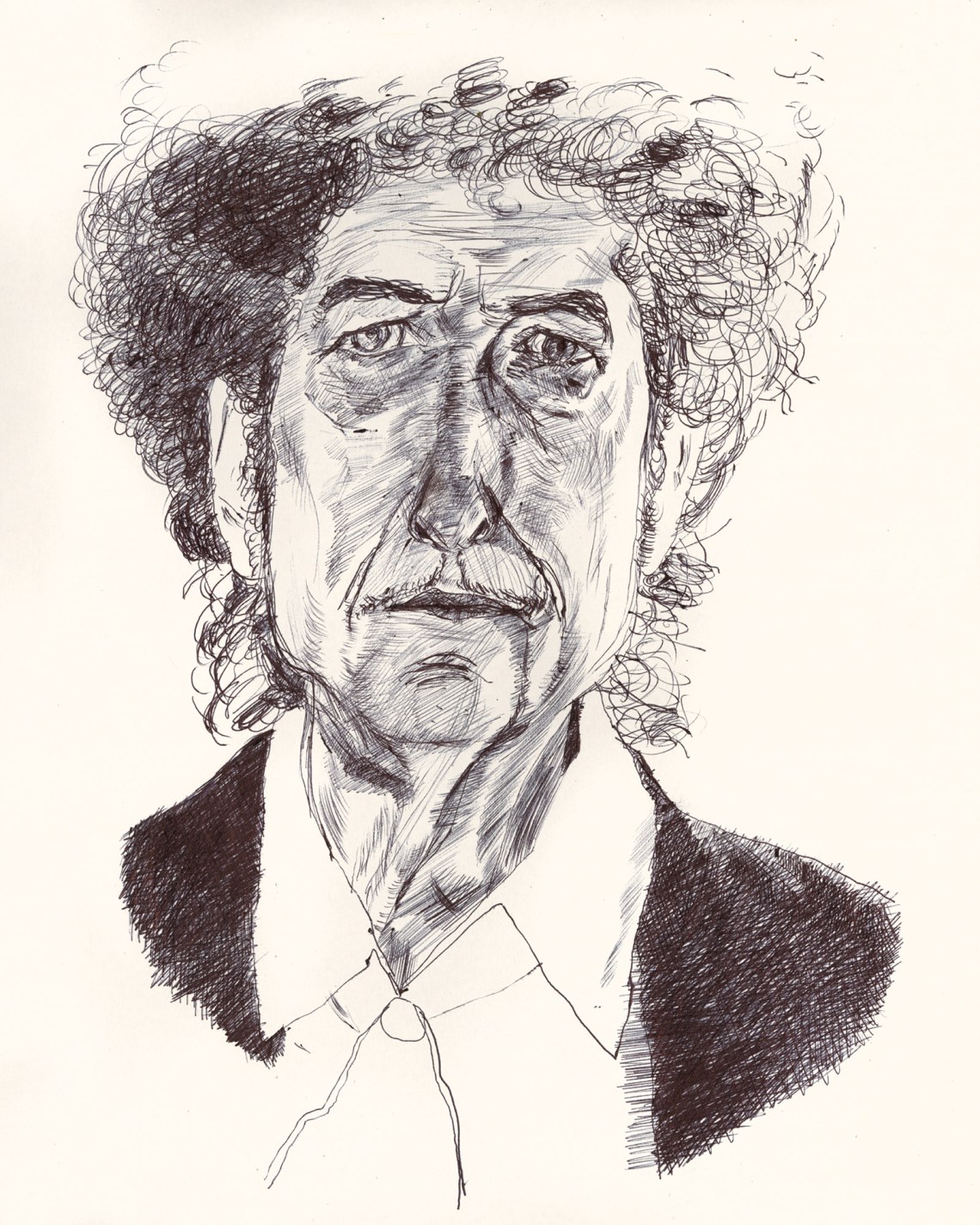

Dylan, at eighty-one, is now older than Henry Mishkin was in 1993. Here is a passage from his chapter on the Who’s stammering, venomous anthem “My Generation”:

You’re looking down your nose at society and you have no use for it. You’re hoping to croak before senility sets in. You don’t want to be ancient and decrepit, no thank you. I’ll kick the bucket before that happens. You’re looking at the world mortified by the hopelessness of it all.

In reality, you’re an eighty-year-old man, being wheeled around in a home for the elderly, and the nurses are getting on your nerves. You say why don’t you all just fade away. You’re in your second childhood, can’t get a word out without stumbling and dribbling. You haven’t any aspirations to live in a fool’s paradise, you’re not looking forward to that, and you’ve got your fingers crossed that you don’t. Knock on wood. You’ll give up the ghost first.

It is surprising to find the bratty sneer of “My Generation” (“I hope I die before I get old”) moved to an assisted-living facility. Dylan, though, is “being wheeled around” not by nurses but by buses, as he moves from town to town and continent to continent on his Never Ending Tour, which most observers date to 1988. He marked his three thousandth performance in 2019. That’s a hundred shows or so a year, going back thirty years. After a hiatus during Covid, Dylan is on the road again in support of his 2020 release Rough and Rowdy Ways, booked into at least 2024, when he will be eighty-three. “This song has a philosophical point of view,” Dylan writes in his chapter on Billy Joe Shaver’s “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me”: “Keep moving, it’s better, let the train keep on rolling. It’s better than drinking and crying in your beer. Let’s go. Let’s go forever. Let’s go till the glacial age returns.”

Did I enjoy Professor Dylan’s class? I did, but it was weird. For example, the instructor played a bluegrass song from the 1950s by the Osborne Brothers, “Ruby, Are You Mad?” His lecture compared bluegrass to heavy metal, “two forms of music that visually and audibly have not changed in decades.” But the slide he showed was of some man shooting a skinny guy in the stomach with a handgun! Why would he do that? It seemed a little violent, especially since the instructor did not provide a content warning.

Each of the chapters in The Philosophy of Modern Song is, like the book as a whole, a kind of crumpled flow chart. The Osborne Brothers no doubt reminded Dylan of Oswald, Ruby of Jack Ruby. The Kennedy assassination has been much on Dylan’s mind of late: “Murder Most Foul,” from Rough and Rowdy Ways, at seventeen minutes the longest track he has ever released, is a prolonged threnody for the slain president, a wending, nearly endless musical cortege.

The mysterious tributaries flow between chapters as well. Dylan’s take on Bobby Darin’s version of “Mack the Knife” picks up again with Kennedy. Darin, according to Dylan, was “merely an altar boy,” while “Sinatra just about invented the Roman Catholic Church.” Darin was a piece of “rejected riffraff”; unlike Sinatra, who performed at Kennedy’s inaugural ball, he had to settle for getting to know “the martyred president’s younger brother Bobby.” Darin and Sinatra were both “shaken to the core” by the Kennedy assassinations. “Their disillusionment would be all too similar,” Dylan writes. “There are other similarities, too, but it’s only in the metaphysical world that you’ll find them.” Class—baffled—is dismissed.

Advertisement

“Way leads on to way,” as Robert Frost wrote. The sixty-six chapters in The Philosophy of Modern Song offer music from Stephen Foster to Warren Zevon, strewn about in no apparent order. The first three chapters celebrate Bobby Bare’s “Detroit City,” from 1963, Elvis Costello’s “Pump It Up,” from 1978, and Perry Como’s “Without a Song,” from 1951: a wallowing country tune, an angular new wave spasm, and a song my grandparents played in the living room when the Grangers came over for bridge. But of the sixty-six selections, thirty were released between 1947, when Dylan was six years old, and 1962, when his first album appeared, shortly before his twenty-first birthday. This strange body of music includes Italian restaurant staples like Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night,” gunslinger melodramas like “El Paso” by Marty Robbins, Vegas gruel by Dean Martin, and the Yale “Whiffenpoof Song” as sung by Bing Crosby, Fred Waring, and the Glee Club. There’s a way to see this canon as the genome that shaped Dylan’s gift, the mundus that greeted the bonneted infans at his planetary awakening. In another light they are the musical reef that he dynamited, utterly obliterated, using only his voice, his attitude, and his harmonica.

There’s a name for the place that both nurtures and imprisons us, the place we simultaneously pine for and detest: home. Bare’s “Detroit City” is sometimes known by its plaintive refrain: “I wanna go home.” But home is “a fantasy of the way things used to be,” Dylan writes: “There is no mother, no dear old papa, sister, or brother. They are all either dead or gone.”

Dylan’s own big hit “Like a Rolling Stone,” written soon after Bare’s version of “Detroit City” scaled the charts, enunciates the word “home,” of course, with special consideration. And in No Direction Home, Martin Scorsese’s great 2005 documentary about his rise, Dylan, hamming it up a little for Scorsese, attributes “mystical overtones” to his childhood discovery of a big mahogany radio with a built-in turntable, at home in Hibbing, Minnesota:

There was a record on it, a country record, a song called “Drifting Too Far from the Shore.” The sound of the record made me feel like I was somebody else. You know, that I was maybe not even born to the right parents or something….

We’d have to listen late at night for other stations to come in from other parts of the country, places that were far away, 50,000-watt stations, coming through the atmosphere.

The motley canon of 1950s songs that make up the nucleus of The Philosophy of Modern Song are best thought of as Dylan’s happenstance musical autobiography, off-kilter, even a bit absent-minded. Surely we’d expect to find songs by Woody Guthrie or Lead Belly in any book about American music written by one of their important disciples, whose own “Song to Woody” honors them both? But Dylan seems committed to little Bobby Zimmerman’s experience of hearing, on his mahogany radio, the Elysian falsetto of Johnnie Ray (who, he tells Scorsese, “had some kind of strange incantation in his voice like he’d been voodooed”). Ray’s voice, he writes, was that of “a damaged angel cast out to walk the streets of the dirty cities,” far from the sanitized blocks of Dallas, Oregon, Ray’s hometown, or from Hibbing.

Many of the styles in this bloc of songs predate rock and roll, and some of them prefigure rock and roll: Johnnie Ray had the transformative emotionality of a rock star, breaking down in tears, at times, during his performances. But baying in desperation is not shouting in anger. The chapter on Ray includes a subcanon of performers who cry during their songs: Roy Brown, the Five Du-Tones, and Sha-Weez are all drafted onto a list headed “Those Who Cry.” There is no such list of those who shout, sneer, or preen, the more common, iconic rock-and-roll displays of excess or transgressive emotion. We find less anger in these tunes than one might expect from the figure who wrote “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” and “Positively 4th Street.” Instead Dylan elevates “the tortured soul, the cowboy heretic,” bearing his loneliness at the end of the road: “The end of beans, bacon and meat, bedrolls, and cow roping.”

This figure wanders, his cultural moment and background lost. When you see Dylan these days, dressed in bolo ties and Nudie suits, it’s clear that he has now cast himself as a figure out of one of these desolate songs. In fact The Philosophy of Modern Song can be read as a tour journal, refracted through one lonely song after another. Dylan praises Willie Nelson’s “On the Road Again” for having “not one downer phrase in it.” But he imagines an alternate take, full of downers:

Advertisement

There could be verses about broken heat vents on the bus, sirens outside hotel room windows, an overeager search at the Texas border, a persistent antibiotic-resistant dose of the clap that spread through the crew after a gig in New Mexico. Dubious microwave burritos, long hauls between laundry days, too much information about the bus driver’s divorce. On the road again.

Unlike Professor Mishkin, Professor Dylan is what is known as a celebrity professor. We enroll in his class partly to see him in person, even from a distance. These figures are usually disappointing in one way or another, phoning it in, getting by on charm. The TA usually has to do most of the work.

Plenty in this book has been delegated to art designers and other abettors, who have built from Dylan’s sparse, delphic statements an attractive hardbound volume, about the size of an intro textbook and with similar graphic features: charts, graphs, stock photos. In the illustrations for Dylan’s chapter on the Eagles’ “Witchy Woman,” we find a beguiling Theda Bara as Cleopatra, some bald eagles, and a girl, nobody in particular, lighting up a homemade pipe made from tinfoil.

What can we glean of the real Dylan, circa 2022? He accepts the climate crisis, but otherwise has settled into a crabby Thanksgiving-table politics organized around codger bullet points (“political correctness,” “women’s lib”); he has used, or seen someone use, TikTok; he is amused by the phenomenon known as a “guy crush”; he once streamed Sunset Boulevard on his smartphone; he calls the substance known in his heyday as “grass” by its current name, “weed.” It’s reassuring somehow to find out that Dylan is “one of us only, pure prose,” as Robert Lowell once said of Mussolini.

Dylan mainly seems to be thinking about the ways he’s lived past the end of his myth, as Anne Carson might put it. His road show, thirty-plus years on, is his primary way of fighting, while at the same time demonstrating, the erosion he’s witnessed in his long lifetime—the loss of big mahogany radios, 50,000-watt stations, carnival culture, gumballs, Robert Blake, Tuesday Weld. Crimes, unimaginable at the time, shocking in their cruelty and brazenness: Robert McNamara, Curtis LeMay. Shakespeare is receding, leaving only a few quotations: “Murder most foul,” “the sins of the father.” Walt Whitman is one phrase: “I Contain Multitudes,” the title of a Dylan song from Rough and Rowdy Ways. If I quiz my students about this corpus of material, I get blank stares. Few of them have seen the Zapruder film, which ran throughout my childhood on a permanent cultural loop.

And fewer every year have listened to Dylan. Many have never even heard him sing. When I play “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” in my classes, I have to prepare them for the sound of his voice, lest chuckles break out in the room during its solemn opening strains. The curious thing about The Philosophy of Modern Song is its near-total erasure of Dylan’s own stamp on American music. He mentions his own music explicitly only once, to flag the influence of “Subterranean Homesick Blues” on Costello’s “Pump It Up.” There is not a single entry in the book for any of the musicians who played on Dylan’s 1975–1976 “Rolling Thunder Revue,” and nobody who joined the Band for the Last Waltz. No Joni, no Neil Young, no Joan Baez. Pete Seeger is the only real representative of the folk scene that Dylan catalyzed, and Dylan seems most interested in his 1967 appearance on the Smothers Brothers variety show.

The 1970s are boiled down to some cover-band staples—“Witchy Woman,” Santana’s “Black Magic Woman,” and the Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’”—along with Jackson Browne’s “The Pretender” and, standing in for all of punk, the most obvious song by the Clash, “London Calling.” Dylan wants to revive Cher’s 1971 “Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves” in part for its association with Sonny Bono, whose “greatest achievement was as a congressman, where he helped pass the Sonny Bono Act, which extended copyright terms for all songwriters.” At times The Philosophy of Modern Song feels like a sci-fi project set in a parallel universe where Bob Dylan stayed home in Hibbing and inherited his father’s electrical supply store.

It doesn’t matter, though. Dylan long ago learned the magic trick of making his presence feel both gossamer and fundamental. He’s in every daffy insight, every constellation of thoughts. You hear even an unctuous tune like “Witchy Woman” with new ears when Dylan’s listening along with you. There is a politics to this book, subtly expressed, which has to do with the necessity of having a shared popular canon, skimmed mostly off the top, nothing too curatorial or obscure. In the 1960s, Dylan writes, “everybody was tuned in to the same TV shows”:

People who wanted to see the Beatles on a variety show had to watch flamenco dancers, baggy-pants comics, ventriloquists, and maybe a scene from Shakespeare. Today, the medium contains multitudes and man needs only pick one thing he likes and feast exclusively on a stream dedicated to it.

Instead of Walter Cronkite, we have “left-wing whining, right-wing badgering, any stripe of belief imaginable.” If you want to find something about “lemming suicides” or “the fact that whale songs have inexplicably lowered in pitch 30 percent since the sixties,” you’ll find it not on Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom but “buried on animal documentary channels.”

I had an insight into Dylan, after all these decades of singing along. I was driving in the mountains, listening to his extraordinary 2012 song “Tempest,” about the sinking of the Titanic. It’s one of those songs, like “Desolation Row,” with a huge cast and nearly infinite verses; it’s fourteen minutes long, and nothing about the shape of the song tells you whether you’re nearing its end. It’s also weirdly buoyant, like something the doomed ship’s band might have played in one of its ballrooms as the vessel disappeared into the frozen Atlantic. Infinitely, deeply, mesmerizingly moving, as one after another passenger is consigned to agony. And then you realize: Did Dylan just mention Leonardo DiCaprio, star of the 1997 film Titanic?

They battened down the hatches

But the hatches wouldn’t hold

They drowned upon the staircase

Of brass and polished goldLeo said to Cleo

“I think I’m going mad”

But he’d lost his mind already

Whatever mind he had

The ribbon of culture passes through some strange byways and thoroughfares before it ends up in Dylan’s mind. Of course Leo’s on the deck of the Titanic—we all saw him there. Dylan was once asked about the choice to include him. “Yeah, Leo,” he replied. “I don’t think the song would be the same without him. Or the movie.”