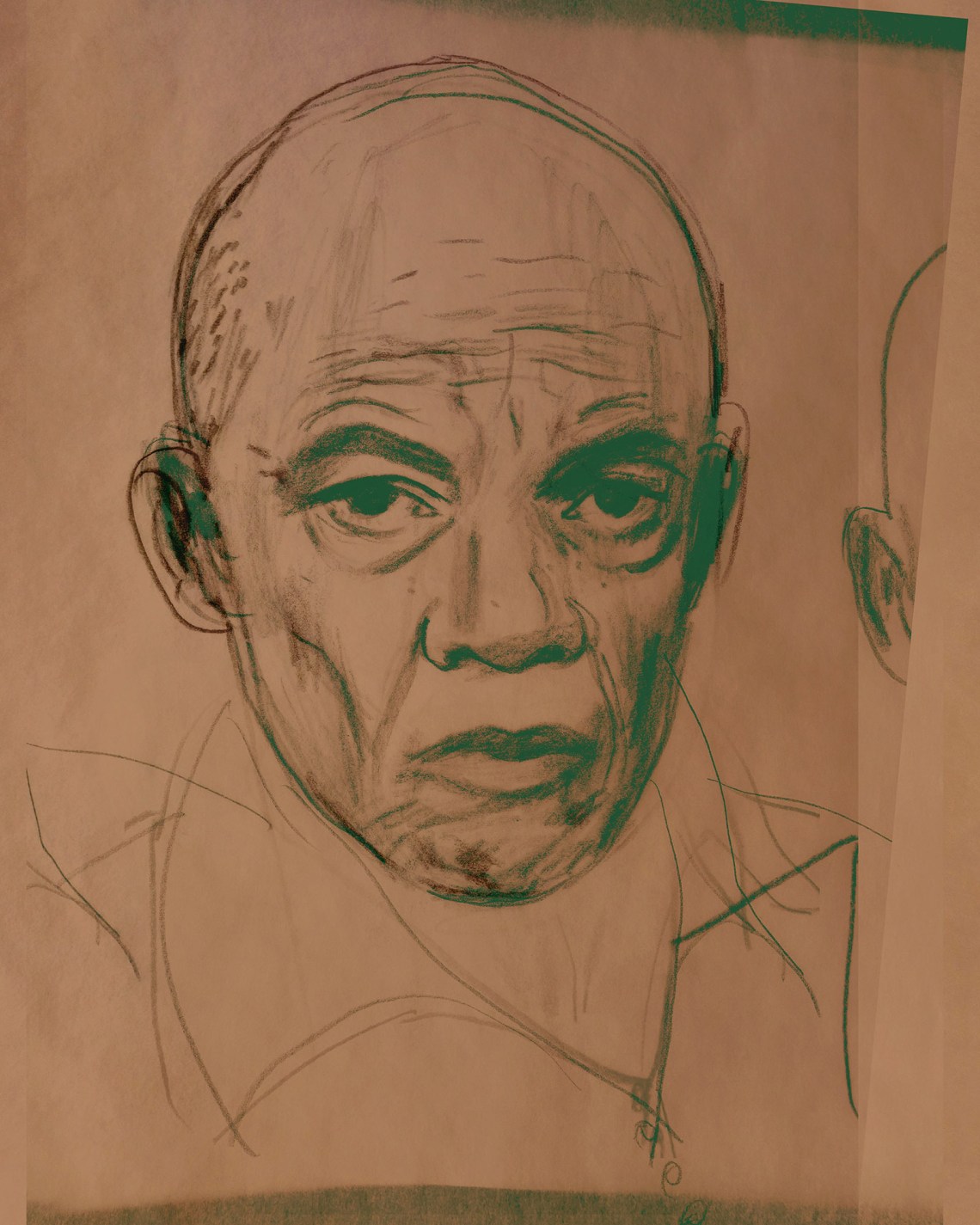

John Edgar Wideman is that splendid thing, a black intellectual—full of grandeur and agony, rage and poise. He’s also a man. He writes about fathers, brothers, fugitive boys: a harrowing fiction of masculine hurt. But his heroes are often middle-class writers who try to do research. They take notes, tape interviews, or delve into archives, hoping to end their alienation and raise the dead.

These are ruthless books. Wideman wants to capture black history and somehow heal the pain—but the writing snaps, chokes, slides, flees. It brims with allusions and rends its own flesh. A sentence can be coiled, limpid, clenched like a fist, or burst through its levees and stream down the page. Plots veer and recur or are bluntly abandoned in this rigorous program of textual scrambling, which might seem “postmodern” if Wideman weren’t so singular: he stands outside movements, refuses fashions, and for a half-century has held fast to his kingly obliquity. This is the start of “Death Row,” from his most recent collection of stories, Look for Me and I’ll Be Gone (2021):

Think of layers within layers. Within layers. Think of getting dressed in winter for a long walk in the cold. Think of undressing to make love. Think of covering yourself after having your clothes ripped off and being raped. Think of layers of chain of command in an army. Think of layers of give-and-take layering who wins and loses in an economic system. Think of putting on makeup. Think of layers of fiberglass insulation to seal warmth in a home or think of the bulge of absorbent cotton and waterproofing material layering a baby’s crotch inside a cute jumpsuit or bulge of adult pamper layering an old person’s bare skin before underwear….

“You keep writing those buggy books,” says Robby to his brother Thomas in the novel Fanon (2008). “Always fussing cause you say nobody reads them, but you keep writing them. I dig it.” Robby reads them in prison, by the light in his cell.

That’s where the swerving paths of Wideman’s fiction lead: to the prison, the plantation, the ghetto, the street, places where black people are brutalized and must fashion a life. From that life comes a world of values and language, which his characters long for once they manage to leave. Eddie Lawson, in the first chapter of Wideman’s first novel, A Glance Away (1967), walks out of rehab and waits for the bus. It will take him north, to a sour mother and stifled sister in their old house in a gutted city. The thought brings him a deep relief. “I am going home, again and again repeated somewhere inside his chest, from all of this I am going home.” We know this home. In the book’s prologue, we see Eddie’s mother, Martha, give birth, as her father, DaddyGene, looks on:

Of all the damndest things me drunk on these stairs upgoing to little skinny Martha, firstborn of my brood to see firstborn of her still secret brood somewhere hidden in loins of dark boy who came and courted and caught little Martha skinny’s fancy, how drunk I am on that first drink neverending after paper is hung on walls.

The early debt to Joyce is profound, but A Glance Away, which Wideman published at twenty-six, strides proudly into the space cleared for him by Baldwin. The prologue is pierced by mysterious voices, one of which sings “Go tell it on the mountain”—a Negro spiritual and the title of Baldwin’s debut novel. Wideman’s book, too, drops its hero on a pile of ancestral strife. A strange force flings Eddie into wrathful confrontations with his mother, his friend Brother, and the white professor Thurley, a man who adorns his sadness in a literate hypocrisy. A Glance Away lays out the themes that form the core of Wideman’s work: the drama of exile and the pain of return, the impotent pathos of the life of the mind.

That pathos thrums through Wideman’s own life. He was raised in Homewood, a black section of Pittsburgh where generations of his family have lived; he was hoisted out of the working class by scholarships to the Ivy League and Oxford; and this ascent has produced a corpus of thrilling self-flagellation. His writing refuses to trust itself. He feels sliced from his nourishing roots. What can you possibly write if you’re walled off from what you are? How do you do justice to blackness once you’re lodged in the bourgeois world? Cecil Braithwaite, the hero of Wideman’s second novel, is a lawyer who has married a white woman and feels locked in an impossible role. Eventually he flees to Africa; the book is called Hurry Home (1970).

Advertisement

But Cecil’s name springs up again in Wideman’s third novel, The Lynchers (1973). This time he’s a figure of middle-class mawkishness, “that lame ass lawyer Cecil Braithwaite” who “ran his civil rights bullshit down to the police chief” when someone named Littleman landed in the hospital after beating an officer. Littleman had been standing alone on the steps of Woodrow Wilson Junior High, howling insurrectionary provocations at the black children. And they’d watched, riveted and perplexed, as the old man with a big voice and braces on his legs was rushed by the cops, then swung back with his cane. Littleman is angry, vulnerable, compelled by bloody visions—and marks, in Wideman’s fiction, the birth of a new motif: the threat of catastrophe and the voice of revenge.

Black revenge. And that voice is soaring, absolute. At the center of The Lynchers is an elaborate plot, hatched by Littleman and planned with three accomplices, to murder a white policeman. It doesn’t matter which one. What matters is when, where, and how he will be slaughtered, and the best way to mutilate the corpse and stage its public display. This is to be a feat of political theater—a “lynching in blackface” and declaration of war. Littleman dreams that this spectacle will release a stream of black fury, the hate that throbs beneath the skin of social life: “For a while the impact of Watts burning or revolutionaries kidnapping and ransoming a judge are raw, crude sources of energy. They are answers in progress to the questions you have been afraid to raise.”

The Lynchers was published just past the apex of Black Power and, crucially, at the tactical peak of the Black Liberation Army, an urban guerrilla faction that sprang from a split within the Black Panther Party and carried out between forty and sixty prison breaks, hijackings, heists, and assassinations. (Assata Shakur, the most famous BLA militant, was shot and captured just days after the book’s release.) So Littleman is a hyperbole, as well as the spirit of the age. But one of his accomplices is Wilkerson, a schoolteacher and foiled writer. He is afraid to raise certain questions—like how to express love or lead a life shaped by pain. He wanders the novel as a Widemanesque shadow:

Wilkerson seldom spoke of his parents, but he was black, had started poor and made a humble dent in the system, had a profession…. Second generation son with his catch as catch can affluence, sorry for his parents, sorry for himself. Sorry because they gave him everything and nothing. Sorry because he respects qualities in them that transcend the cramped physical poverty of their lives, a poverty he doesn’t change because he isn’t that far out of the woods himself. Sorry because reverence is a cheap way of quieting his guilt. Wilkerson’s scared rabbit nerves, his stiff white shirts.

Those “scared rabbit nerves” are the true subject of The Lynchers, as Wilkerson blooms into a model for a black petty-bourgeois paradox: torn between his anger and his advantages, he swings from bombastic hysteria to neurotic self-censure. He’s appalled by his own rage. But he sees Littleman as the bearer of a black truth, the truth of torture and insurgency, exploitation and reprisal, a saga whose latest episode was the militant 1960s.

Littleman, Wideman—the names are nearly opposites, and the former may embody the author’s ravaged, repressed side. Littleman is a black intellectual with none of the dignity, none of the virtue, none of the exquisite judiciousness or love of the world. He isn’t seeking equality, recognition, or even political victory, but the shattering pleasure of cataclysmic revolt: “When we lynch the cop we declare our understanding of the past, our scorn for it, our disregard for any consequences that the past has taught us to fear.” Stripped of gravitas, his language grows ragged and vicious, a screaming engine of total negation. “I write at night,” Littleman says, but he destroys the pages each day. “Oblivion for my words appropriate because my people have always written their history with their mouths.”

The claim is cutting. It spits on the very book in our hands. And raises old problems: Can written English capture the true tones of black speech? Does transcription of that speech amount to a betrayal? And does the gap between black English and its shape on the page prove the futility—the prestigious pointlessness—of even the most radical black intellectuals? Wideman’s first three novels all deploy, in various combinations, the themes of violence, class difference, and the black American family. But perhaps the books had missed his own family. They’d failed to render how English was gripped and manipulated by the black mouth and black breath—all the trilling idiosyncrasies of the world he’d left behind. This was a special language. Forged by African oral traditions and the terrors of the New World, it defied the authority of Eurocentric culture: its styles, its values, its laminated forms. Those forms had been part of Wideman’s rise and assimilation, but he chose to make a break. For seven years he experimented, as his writing searched for the sound of his past.

Advertisement

From this effort came his Homewood trilogy: the story collection Damballah (1981) and the novels Hiding Place (1981) and Sent for You Yesterday (1983). The books are acts of flinching devotion, as they reach into his family’s history to enliven its pain and lore. Characters dash in and out of view and the action spans centuries, but fixed at the center is Homewood. Wideman had come to see himself as a translator, alert to how vernacular might be pinned to the page. In “Tommy,” a story in Damballah, the protagonist takes a walk and is bathed in the talk of the street:

Hey man, what’s to it? Ain’t nothing to it man you got it baby hey now where’s it at you got it you got it ain’t nothing to it something to it I wouldn’t be out here in all this sun you looking good you into something go on man you got it all you know you the Man hey now that was a stone fox you know what I’m talking about you don’t be creeping past me yeah nice going you got it all save some for me Mister Clean…I’ma see you straight man yeah you fall on by the crib yeah we be into something tonight you fall on by.

The braiding of repeated phrases, the resistance to punctuation, the way voices twist and recombine in a frothing torrent of collective speech—not every passage is like this, but enough of them are. This is a Faulknerian modernism crossed with a black radical impulse: Homewood establishes itself in the text as both a place and a pained chorus. “The three books offer a continuous investigation,” Wideman later explained, “from many angles, not so much of a physical location, Homewood, the actual African-American community in Pittsburgh where I was raised, but of a culture, a way of seeing and being seen.” This is from the preface to The Homewood Books (1992), which collected the trilogy in a single volume—the first time that any part of it was published in hardcover. The modest sales of Wideman’s earlier novels, along with his “naive hope that lower prices and softcovers might entice a larger black readership,” meant that the books were issued first in paperback. Sent for You Yesterday won the PEN/Faulkner Award, to the embarrassment of Wideman’s publisher, who hadn’t even bothered to submit the novel for the prize.

The PEN vaulted Wideman to literary celebrity. Suddenly he was a palatably desolate black public voice. An essay he published in The New York Times in 1988 had a booming title worthy of Ralph Ellison or Richard Wright: “The Black Writer and the Magic of the Word.” But the piece was smaller than that, more inward. It explained the recent shift in Wideman’s attitude and style:

In the fiction I have published during the last several years, I have been trying to recover some lost experience, to re-educate myself about some of the things I missed because the world was moving so fast…. In contrast to Thomas Wolfe, I can go home again, listen again.

A vow to return to the people leads to the birth of a bracing art. This is moving—and revealing. Decades of black modernists and avant-gardists, jostling under the banners of communism, socialism, nationalism, and Pan-Africanism, have been propelled by some form of this project: a clashing, radical tradition that reached a peak in the 1960s. That was when “the world was moving so fast”—when the thrust of the black movement called for valiant new theories of art and its place. “Fuck poems,” Amiri Baraka wrote in 1966, “and they are useful.” Within two years, Baraka and the poets Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, Haki Madhubuti, and Gwendolyn Brooks had all sworn allegiance to the Black Arts Movement, whose mission, as proclaimed in a manifesto by the playwright Larry Neal, was to be “the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept” and thus “radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community.”

But Wideman was alienated. His Sixties weren’t theirs. He’d been an athlete at the University of Pennsylvania, then a Rhodes Scholar, and then a debut novelist and professor who, as he later told the writer Caryl Phillips, had attended exactly one demonstration for civil rights, “back in 1967 in Iowa City—a protest march—and by that time, it was no big deal.” At Oxford, he’d learned to like his “oblique angle” to the eruptions in the US. And he’d spent the Black Power years constructing fictions that were touched by—but by no means fixed to—the movement for revolution. So in the Times essay, he longs for “some of the things I missed”: the feel of that now-mythic era of dreams and assassinations.

And ultimate collapse. For all the sensuous self-inspection of “The Black Writer and the Magic of the Word,” one thing goes unmentioned—an event that took place between The Lynchers and the Homewood trilogy and has exerted pressure on all of Wideman’s work since. In 1976 his brother Robby was convicted of second-degree murder. Robby was the younger brother: the wayward one, the obstreperous one. He had no academic aspirations, won no scholarships; his fury was never ennobled as anomie or enshrined as “challenging” art. He stayed poor. But he’d been a teenager when Black Power came crashing through Homewood, and politics flushed his life with meaning and gorgeous force. He was lost when the movement died; he eventually became addicted to drugs. In 1975 he took part in an armed robbery, and his partner pulled the trigger. Robby was handed the harshest sentence short of execution: life in prison without parole. And in 1986 Wideman’s sixteen-year-old son Jacob, in a shocking incident that Jacob himself has never tried to explain, killed a classmate on a camping trip. He, too, was sent to prison for life. So two Wideman men, under vastly divergent circumstances and more than a decade apart, were fed into the American anomaly of “mass incarceration.”

Prison now stands at the heart of Wideman’s writing. Some of his most bursting, extravagant plots drag us back to the bleakness of penitentiary visiting hours—the soaring walls, the clanging gates, the ludicrous rules, the wounded speech. Prison is the metal mouth that devours the men he loves. Love mixes with his guilt and drives him, painfully, to write. Tommy, the protagonist of Hiding Place as well as the eponymous story, is a young fugitive based openly on Robby, to whom Damballah is dedicated: “These stories are letters. Long overdue letters from me to you. I wish they could tear down the walls. I wish they could snatch you away from where you are.”

In 1984 Wideman published a memoir about Robby’s imprisonment, Brothers and Keepers, in the hope that exposing the system’s waste and malice would finally bring him home. It didn’t. That failure dredges up the old questions: about the link between art and commitment, and about the place of the black writer in a culture slashed by “race.” If he were a less difficult stylist, Wideman would quite simply be the writer of mass incarceration. No other major novelist has poured such intimate anguish at prisons into book after book after book. Incarceration, in Wideman’s writing, is the crux of modern life: where the shrieks of chattel slavery meet the drone of spinning capital, as the mind chokes, the body breaks, words melt, and force rules.

Today Wideman lives at a luxe remove from the pressures that put many black men behind bars. He dwells on that remove and offers what he can: his books, his sensibility, the painful pleasures of analysis. Beneath the rippling syntax lies the violence of the state:

I listen to my brother Robby. He unravels my voice. I sit with him in the darkness of the Behavioral Adjustment Unit. My imagination creates something like a giant seashell, enfolding, enclosing us. Its inner surface is velvet-soft and black. A curving mirror doubling the darkness. Poems are Jean Toomer’s petals of dusk, petals of dawn. I want to stop. Savor the sweet, solitary pleasure, the time stolen from time in the hole. But the image I’m creating is a trick of the glass. The mirror that would swallow Robby and then chime to me: You’re the fairest of them all.

Is this, from Brothers and Keepers, the right language to describe abuse and immurement, the stripping of rights? Should it be the language of sociology, turning like a telescope to take in the system of black life, or the first-person narrator, unrolling his loops of memory? Or a black language—the speech that flowed through Wideman’s childhood and pounds the prison walls:

Being locked up, you know, I got nothing but time, plenty of time to read. Pick up your weird shit and whoa, sometimes it makes perfect sense to me. Probably because you’re my brother. Plenty times I don’t agree with them knucklehead ideas I been hearing from you my whole life, but I like to hear your bullshit anyway. Funny, you know, the craziest shit’s what I like best. When you get off on words and get to rapping and signifying and shit. Getting off on shit like we do in the yard. Just to hear our ownselves talking sometimes, just to say goddamn words we ain’t gon hear less we say em. Guys hanging in the yard talking crazy stories. Know what I mean.

Just to hear our ownselves talking: Robby voices Wideman’s own hope. But this Robby is fictional and the brother of Thomas—another Wideman stand-in, who appears twenty-four years later in Fanon. All the classic Wideman elements are in place: the incarcerated brother, the legacy of black militancy, and the tormented writer who must hold both in his head at once. (If Wideman were younger, white, or more tickled by middle-class manners, he’d be trumpeted today as a master of US “autofiction.”) Aghast at Robby’s imprisonment, Thomas is seized by the desire to write a book about the Martinican revolutionary Frantz Fanon. But the effort fails. Thomas falls into reverie, he’s busy teaching a class, he’s sickened by the news, he’s consumed by his past. He imagines, in delirious detail, the final moments of Fanon’s life. (Fanon preoccupies Wideman and is invoked in many of his novels and essays.)

In a jarring section in the middle of the novel, Thomas drops out completely, as a character named John Edgar Wideman strides down the blasted streets of Homewood with Jean-Luc Godard, pleading with him to make a movie about the neighborhood. “Can Homewood’s language,” asks the Wideman character, “be reduced one-on-one to another language—film for instance. What’s the point of language if another language renders it transparently, disappears it.” Speech itself is faulty and weak; it cracks, escapes, and betrays you. In Brothers and Keepers, Robby enters the courtroom, dragging iron chains. Wideman stands there, wordless. Trapped in that “citadel of whiteness,” enclosed in its lethal language, he locks eyes with his little brother and raises a black fist.

Failed revolution is another Wideman motif—or if not failed then stalled, soured, inverted, unfinished. The Sixties still transfix him with all their insane possibility. In Brothers and Keepers, 1968 is the glory of Robby’s life, when he becomes a teenage militant and leads a high school strike. He styles himself as an orator of the movement:

Malcolm and Eldridge and George Jackson. I read their books. They was Gods. That’s who I thought I was when I got up on the stage and rapped at the people. It seemed like things was changing. Like no way they gon turn niggers round this time.

The scene recurs in Fanon, when the fictional Robby is part of a group of protesters brought to see the principal, who asks, with cutting simplicity, what they want. “We want what you want. We want what you got. Want your money, your watch, your nice house up on Hiland Avenue, your car, some pussy from your cute little four-eyed daughter.”

In Philadelphia Fire (1990)—perhaps the most powerful of Wideman’s novels—a writer named Cudjoe (after one of the last slaves kidnapped from Africa, who lived into the twentieth century) is consumed by a quest to find a little black boy who was filmed running, fully naked, from a burning house. The book is based on the infamous 1985 incident in which a police helicopter, on the orders of the black mayor of Philadelphia, firebombed a building occupied by MOVE—a Black Nationalist group that embodied the thrashing Sixties energies the city sought to purge. Eleven people were killed and over 250 left homeless, as sixty-one houses—a vast slice of West Philadelphia—were burned to the ground.

Cudjoe roams the neighborhood. He floats down the mutilated avenues. He tries desperately to get information from a former member of the group, a woman whose fierce hostility proves the distance between them. Cudjoe had hoped to close that distance, believing that his horror could span the canyon of class: “He’ll tell Margaret Jones we’re all in this together. That he was lost but now he’s found.” But he’s still a writer, an observer, an intruder. The bombing blurs into fantasy, a mere occasion for his pain. “Pretend for a moment that none of this happened,” Wideman writes. “Pretend that it never happened before nor will again.”

Look for Me and I’ll Be Gone could be the title of virtually any of Wideman’s books. These stories, too, are transfixed by abandonment and escape, and feel like a frieze of his formal repertoire: family sketches, gnomic allegories, and historical fictions about figures from the black past. (“Lost Love Letters—A Locke” is partly written in the voice of the philosopher-modernist Alain Locke.) And there are the requisite, blistering pieces about his incarcerated brother and son. “Last Day” begins:

Sometimes going to see my brother in prison felt like when you hear a person call you nigger, a somebody you may not even know addressing you, a stranger who suddenly becomes intimately close by establishing a boundary, drawing a line and crossing it simultaneously with the n-word as if the two of you, separated by that line, have known each other a lifetime…

The sentence goes on like this for two pages, strapping on clause after clause, both fueling and arresting its own sputtering propulsion as Wideman elaborates on his dark semantic point. But it all starts with his brother. The brute fact of a caged relative fans out into a wounded philosophy of language. Wideman’s stories, more than his novels, tend to be driven by this essayistic impulse. Sometimes they even open with a query or proposition—little lexical experiments performed in the laboratory of his style:

I have always thought figment a funny word. Not ha ha funny. More like odd, strange. Fig plus ment. A fig a fruit and I can almost see one when I read the word fig. But ment. What’s meant by ment. What happens to a fig when you add ment to it.

This is the beginning of “Someone to Watch Over Me.” By the end of the two-page story this narrator has run through “segment,” “fragment,” “pigment”:

Consider, for instance, how many permutations, combinations or algorithmically determined mutations of meaning language can produce by combining in a single sentence words that start with fig, pig, seg, or frag. Consider how in our society a figment of pigment segments and fragments a society.

The play is streaked with dread. One might venture a comparison—conspicuous differences notwithstanding—to the short-short stories of Lydia Davis: some fear or pain or longing is rattling in the locked box of this voice. (His 2010 collection Briefs is an even closer match.) But Davis’s deceptive whimsy zips in various directions, while Wideman’s investigations are lashed to the mast of blackness.

Look for Me and I’ll Be Gone may mark the climax—the most vivid, explicit point—in the path that Wideman has beaten since the Homewood books, a phase whose specific features shine most brightly in his short stories. He’s embarked on a kind of philosophy. That is, a quasi or even antiphilosophy, a theory slitting its own throat—a metaphysically dilapidated philosophy of blackness. Yes, he knows that “race” is a construct built for punishment and social control, and that there’s no “essential” blackness that flows through history unchanged. He also knows he has a people. Hence the split psyches and imploded narrators who roam and rule his work and inflict their sense of fracture on the level of style and form, such that blackness becomes an object of abstraction and analysis and makes him grasp at a frantic language packed with logics, systems, schemes: the “fragments” and “segments” above; how the word “nigger” draws a boundary; even the “layers within layers” at the beginning of “Death Row.”

He hopes to master the racial paradigm. So these are sketches, diagrams, theses, parts of a devastated structuralism; Wideman slaps together models only for them to teeter and collapse. The latest humiliation to the bourgeois writer may be by his own fantastic theories, none of which can give an answer to the basic question of what blackness is. A culture or a specious category? A way of being, thinking, speaking, or a violence from without? What can possibly be extracted from this precious, monstrous thing, which lives in the scream of the police siren and in the faces of those you love?

“SLAVE LIVES MATTER,” Wideman writes—a burst of laughter in the abyss. The words appear in “BTM,” among the most startling pieces in Look for Me and I’ll Be Gone. Its opening maneuver is frankly peevish and perverse: a description of a pleasure cruise whose passengers are exclusively large black women. The language is beastly, relishing. It licks its lips at the provocation and debases the women themselves. The narrator asserts with sadistic pleasure that their size and poor health are symptoms of the blackness stamped upon them, itself a lamentable artifice to be destroyed by any means. If the blade of racial terror is stabbed so deep in daily life, there’s nothing to be pious about and no point in being polite. By the end he hates his own cruelty. And he’s ashamed of having thought that petulance could raze the edifice of race.

It will take more than that: more than viciousness, insouciance, pathetic self-deceptions. The question of what freedom looks like is a fixture of Wideman’s project, and here is made more poignant by the story in which his brother is at last released. But for all the hopes of homecoming and visions of reunion, the writing always splinters against a countervailing force: the force of 1968, Fanon, MOVE—and of Littleman. He’s a howl against the unforgivable. So Wideman’s fastidious analyses and erudite allusions, his wincing reflexivity and fully baffling patches look like ways of handling the terror of Littleman’s obliterated daily writing: words with nothing to posit but chaos and nothing to hope for but flames.

“Write your sixties novel,” a character in Philadelphia Fire says to Cudjoe with a sneer. “Forget the fire. Play with fire you know what happens. You’ll get burnt like the rest of us.” But Wideman dreams of a great burning. Which is to say that against the constant disavowals and professions of futility, in spite of the stinging failures and the intractable force of time, revolution still stalks this project. These fictions insist that beyond the liberal slogans lies the wish of the dispossessed: not to swap out a single master but to incinerate the social contract. Wideman was once too late to produce a revolutionary literature; now he may be too early. But he can offer a form of writing that in its assaults and marvelous shattering clears a space to be filled by others. He can’t help but picture rupture near the end of “BTM”:

I wish for an overwhelming bunch of people, lots of them of all colors, people with large fat sticks to arrive suddenly, materializing within the video framed on my TV screen. I yearn for irresistible waves of good citizens intervening who humiliate, shame, hurt the cops, bruise and bloody them in public on millions and millions of screens like mine, until the cops perhaps awaken. I can imagine no other remedy, no other way to teach that the evil cops perpetrate on others, sure as shit, punishes them likewise. Not exactly a remedy or a cure. Nor a chance to get even by inflicting pain. Not the false, futile, Old Testament, eye for an eye, tooth for tooth revenge that sanctions more destruction but never restores what’s been lost. Instead, I’m demanding stunning ocular proof that alerts everybody on this occasion and forevermore, to a line in the sand.

The fantasy is nothing less than a “program of complete disorder”: the paradoxical formulation of his beloved Fanon. The moment itself is brief, and Wideman once more takes it back, but it repudiates the charge that this writer is a fatalist. Things can change—by excruciating sacrifice and social explosion. Our hero braces himself, and readies his brutal blues.

This Issue

December 22, 2022

Naipaul’s Unreal Africa

A Theology of the Present Moment

Making It Big