If you’re searching for the perfect, alarming symbol of our perfectly, alarmingly divided polity, you might look to the 142nd district of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, which lies northeast of Philadelphia and just west of Trenton, New Jersey. It is the home of the Sesame Place theme and water park, wedged in between the Oxford Valley Mall and Jefferson Bucks Hospital, where since 1980 joyous children (including my own one sunny afternoon some years ago) have cavorted and splashed with Elmo, Big Bird, and the rest of Jim Henson’s brigade.

Pennsylvania’s General Assembly has, besides fifty state senators, 203 state representatives, each of whom represents about 64,000 residents. (It is the second-largest state legislature in the country, behind only, and oddly, tiny New Hampshire, which elects four hundred representatives to its lower house, or one for every 3,473 residents.) After the 2020 election Pennsylvania’s districts were divided 113 to 90 in favor of the Republicans. But in the 2022 midterms, the Democrats made a strong run at taking over the majority. The balance of power hung on a small number of districts—any one of them could have flipped control to the Democrats for the first time since 2010.

The 142nd was one of those districts. On the Thursday after the election, its Democratic candidate, Mark Moffa, led his Republican opponent, Joe Hogan, by precisely two votes, 15,095 to 15,093. In other words, control over vast powers—industrial and environmental policy in one of the country’s most politically important states, and how the state government might (or might not) intervene in the 2024 presidential election—hinged, at least momentarily, on two voters in Bucks County: the timing of their traffic lights, the severity of their children’s flus, an impromptu decision by either to stop off at the ACME supermarket before heading to the polling place. (By the following week, Hogan had inched ahead—but Democrats did take control of the lower house.)

That is at once how random and how predetermined American elections have become. When so many outcomes are decided so narrowly, we can conclude two opposing things: that the whole affair is completely capricious, and that the outcomes are at the same time a matter of dueling iron wills. Consider:

In Colorado’s eighth congressional district, a new district, Democrat Yadira Caraveo defeated Republican Barbara Kirkmeyer by around 1,700 votes out of about 220,000 cast, making Caraveo, somewhat surprisingly, the first Latina to represent Colorado in Congress.

In New Mexico’s second congressional district, Democrat Gabe Vasquez defeated Republican incumbent Yvette Herrell by about 1,300 votes out of some 190,000 votes cast.

In Iowa’s third district, Republican Zach Nunn beat Democratic incumbent Cindy Axne by about 2,100 votes out of more than 300,000 cast.

I could go on like this without including the razor-thin high-profile races covered extensively by cable news: the Nevada and Georgia Senate seats, the governor’s race in Arizona, the Colorado House race where ultra-MAGA Republican Lauren Boebert was finally declared the winner, by 551 votes, on November 17.

This is our new condition—tight races between two armies of voters, each marching to the polls with the conviction that victory for the other side would be not merely an unhappy result but calamitous for the republic. We have seen a corresponding uptick in turnout. Historically, turnout for US presidential elections has been reliably north of 50 percent (still quite low by global standards), while turnout during midterms has been much lower. In the eleven presidential elections from 1972 to 2012, according to figures from the United States Elections Project, turnout averaged 56.1 percent. In the eleven midterm elections from 1974 to 2014, the average turnout was just 39.4 percent. But all that began to change in 2016—the age of Trump. The presidential turnout in 2016 was a bit higher than average, at 60.1 percent. In the 2018 midterm, turnout was 50 percent, the highest for a midterm since 1914. Then turnout in the 2020 presidential race set a modern record at 66.8 percent, the highest since 1900. We don’t have this year’s turnout figure yet; it appears that it will fall a bit short of the 2018 mark but still be between 46 and 47 percent.

Political scientists awaited this election to test whether 2018 was an aberration or a sign of a new age for citizen engagement. The answer appears to be the latter, with voters driven largely by passions aroused by one man. In this one sense, as the political scientist John Sides of Vanderbilt University remarked to me after the election, Donald Trump has “strengthened American democracy, if we measure it simply by, ‘Do people care about politics? Are they engaged? Will they pay the costs of showing up to vote?’” A cold comfort, perhaps, but a development no small-d democrat should abjure.

The results were nothing short of a humiliation for Republicans. Yes, they did retake the House of Representatives, but with a net gain of fewer than a dozen seats, far short of their boastful projections. Democrats captured key governorships and, crucially, retained control of the Senate thanks to incumbent Catherine Cortez Masto’s comeback win in Nevada over Republican Adam Laxalt. This gives the party fifty seats, which could grow to fifty-one if Raphael Warnock wins the December 6 Georgia runoff.

Advertisement

There’s a very big difference between those two numbers. In a fifty-fifty Senate, committees are evenly divided, and many committee votes end up deadlocked. But with fifty-one seats, Democrats would hold majorities on every committee. This would be especially important with respect to moving judicial nominations through the chamber more swiftly.

Republican control of the House, even by such a narrow margin, will almost surely mean a ceaseless series of investigations into the Biden administration. Probes into the president’s handling of the Afghanistan withdrawal and his border policies are possible. Marjorie Taylor Greene wants to investigate Nancy Pelosi over January 6—the trials and jailings of the insurrectionists. But at a November 17 press conference, two days after it became clear that they would capture the House, Republicans drew an unmissable bull’s-eye: investigations into Hunter Biden’s Rabelaisian past—his past drug use and sex life, his international business dealings, why his canvases fetch such enviable prices (he’s a painter, favoring large, colorful abstractions that put one vaguely in mind of Klimt and Klee, although the critics’ views are mixed)—will be, they vowed, a “top priority.” The press conference hosts, Jim Jordan of Ohio and James Comer of Kentucky, will chair, respectively, the committees on the judiciary and oversight. And Hunter, they stressed, is not the real target. “I want to be clear,” said Comer. “This is an investigation of Joe Biden, and that’s where our focus will be next Congress.” Not inflation, not the border, but Hunter Biden’s laptop.

After the embarrassing results came in, Republicans did everything they could to pin the blame solely on Trump. Certainly, his favored candidates lost several high-profile races that might have been winnable, like the crucial Pennsylvania Senate seat that Democrat John Fetterman won over Mehmet Oz, and the Arizona gubernatorial and Senate races, where the Republican candidates embraced Trumpist lies and election denialism.

That became the dominant story in media coverage. But the problems went beyond Trump. The Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade, was responsible for a big share of the debacle; voters over and over again rejected the extremist Republican position.

Further, it should be noted that while some of Trump’s candidates lost (most of them won, by the way), Trumpism still won to a frightening extent. A large number of election deniers prevailed—as of this writing, The Washington Post estimated that 176 election deniers won statewide races or seats in the House of Representatives. That antidemocratic extremism surely hurt the party at the polls. Alas, it didn’t hurt it enough; Republicans could not pretend even for two days to be interested in the problems actually plaguing the nation.

The narrow House majority will test Republican cohesion on a recurring basis for the simple reason that such a small margin leaves almost no room for defections. The big day that looms for GOP House Leader Kevin McCarthy is January 3, when the 118th Congress convenes and the members vote on the next Speaker. The Speaker needs a simple majority of 218 votes. McCarthy will obviously receive no votes from Democrats. So he’ll need the votes of nearly every Republican.

If he does get the job, he will be tugged in two directions from the start. The ever-restive Freedom Caucus, the hard-right assemblage of forty-plus members who will be demanding an impeachment of Biden from day one, is generally skeptical of McCarthy. To win their support for his speakership, he will surely have to make promises on impeachment, oversight, and investigations.1 The Jordan-Comer press conference was a sign that McCarthy will set the Freedom Caucus loose.

At the same time, there will be a surprising number of new Republican House members from purple districts—the four winners in New York State, along with winners in New Jersey, Virginia, Florida, Texas, and elsewhere—who are likely to beg McCarthy not to pursue a reckless impeachment, which will not be popular with their constituents. McCarthy’s majority hinges on these members. Still, there’s little—or arguably nothing—in the party’s recent history to suggest it will show restraint on such matters. This leopard’s spots have been apparent for some time.

And the president? Whatever the situation down Pennsylvania Avenue, Biden’s task will be to keep doing what he has been doing. The conventional wisdom asserted that the election results largely vindicated his instincts; this time the conventional wisdom is right. In early September and again the week before the vote, Biden made two speeches on democracy, warning about the threat MAGA Republicans posed to the nation. Many considered them risky. But they did not alienate swing voters, and indeed may have convinced a few.

Advertisement

The student debt relief plan, also much criticized in the pundit class, may have contributed to higher than expected turnout among the young, 63 percent of whom backed Democrats, according to the network exit poll. And while Biden took some deserved heat for being slow to criticize the Dobbs ruling, he did come around. In mid-October, he said that if voters returned majorities to the Democrats,

here’s the promise I make to you and the American people: the first bill I will send to the Congress will be to codify Roe v. Wade. And when Congress passes it, I’ll sign it in January, fifty years after Roe was first decided the law of the land.

That vote, of course, will not take place, with Republicans in control of the House.

The biggest question hanging over Biden remains his age. On November 20, the president turned eighty. This means he’ll be approaching eighty-two at election time 2024; if he runs and wins, he would finish his second term having just turned eighty-six. It would take a rare man who in his mid-eighties could handle the rigors of the presidency, particularly at such a tense moment in history. Vladimir Putin is increasingly cornered and unpredictable, and US officials received intelligence in mid-October that senior Russian military figures have discussed the possibility of using a tactical nuclear weapon in Ukraine. Xi Jinping has made himself dictator of China apparently for life, and right around the time of our election he visited a military command center and gave a speech telling the assembled that they must “comprehensively strengthen military training in preparation for war” (presumably launched against Taiwan). Can an eighty-three- or eighty-four-year-old man deal with such potential crises, all while being investigated and possibly impeached?

In some circles such talk is deemed ageist, but these questions are fair to raise. Biden seems in good health and is obviously clearheaded, despite the right-wing media’s constant efforts to convince America that he is a demented old buffoon. Certainly, Joe Biden at any age would make better decisions than Donald Trump, no youngster himself at seventy-six. Biden told reporters at his first postelection press conference that his “intention” is to run again, and he’ll make the decision early next year.

Meanwhile, Trump has announced that he will run in 2024, to the consternation of the establishment Republicans who criticized him or implored him not to. Republican National Committee chairwoman Ronna McDaniel, a Trump acolyte for years, said before the election that the RNC would stop paying Trump’s legal bills once he announced his candidacy. This is simply a matter of party rules—financial support would constitute favoritism in a party primary—but given the number of rules and conventions flouted to accommodate Trump, the announcement was intriguing.

The matter of Trump’s legal bills raises the question of whether he will face indictment and prosecution: by Jack Smith, the special counsel recently appointed by Merrick Garland to handle the January 6 and Mar-a-Lago classified document probes; by Fani Willis, the Fulton County, Georgia, district attorney; or possibly in the Southern District of New York, to which New York attorney general Letitia James referred the findings of a lawsuit she filed in September against Trump, the Trump Organization, and three of his children. An indictment, to be clear, would likely not hurt Trump in a Republican primary. It would probably help.

Trump’s fate will not be decided by Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell or McDaniel—or even Rupert Murdoch, who turned on Trump after the election with a series of aggressive, mocking covers of his New York Post, culminating in the sneering “Florida Man Makes Announcement” banner the day after Trump declared his 2024 candidacy. It will be determined by the base—the right-wing base assembled and inflamed over all these years by Murdoch and his fellow travelers, delivered into its current state of ecstatic rage by Trump. Those voters chose the nominee in 2016 and will do so again. If their ardor for Trump cools and is transferred to Florida governor Ron DeSantis or perhaps Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin—two pointed targets of Trumpian name-calling after the election—then the party would gladly follow. But if the base still wants Trump—well, things can always change, but there is no evidence to suggest that establishment Republicans have the backbone to protest.

As for the Democrats, their responsibility these next two years will be to continue, without apology, on the economic path they’ve been pursuing—what Biden calls “middle-out economics.”2 There is alas no data that I know of proving that Biden’s economic philosophy helped Democrats in this election. But it obviously didn’t hurt—although many commenters believed that inflation was going to destroy the Democrats and that Republicans were going to convince voters that Biden and the Democrats’ profligate ways were responsible for inflation. Most economists believe that Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan probably did contribute to inflation—Dean Baker, a prominent liberal economist, estimates that it accounted for 2 percentage points of the roughly 8 percent inflation figure—but note that inflation is higher in the eurozone.

Certainly, voters cared about inflation—but they cared about abortion and democracy, too. And maybe they also recognized Biden’s accomplishments. Ten-million-plus jobs gained in two years is a lot of jobs. The CHIPs and Science Act, passed in August, provides nearly $53 billion to boost chip manufacturing in the United States. Just the day after the election, a major chip supplier to Apple announced its intention to build a manufacturing facility in Arizona. These announcements don’t make CNN, but they sure make the local news, and people notice these developments, just like they notice all the highway construction happening on the nation’s interstates because of the infrastructure bill. Whether most people will connect enough dots to give Democrats credit is doubtful, at least while gas prices hover near four dollars a gallon. Of course, it is the Democrats’ job to connect those dots for people, a task to which they’ve often proved unequal. But if inflation is tamed and the economy is strong in the spring of 2024, Biden (or whoever) should be able to make a case to voters that an economic program that rewards work rather than wealth and that seeks to transfer wealth from the rich to the middle and working classes is succeeding.

It is with this perspective that I’m most relieved the much-trumpeted red wave failed to materialize. If it had, pundits and centrist Democrats would have argued that the results were proof that Biden overreached and went too far left. Today, no one is saying that. In fact, some Democrats in purple districts, such as Virginia’s Abigail Spanberger and Kansas’s Sharice Davids, won by embracing the Biden agenda rather than trying to separate themselves from it.

Spanberger’s victory was especially important, as well as telling. The former CIA officer, who became a vocal representative of the moderate faction of Democrats, holds a district that includes some Richmond suburbs but is mostly exurban and rural. It was represented by a very conservative Republican from 2000 to 2014, when he was defeated by an even more conservative Republican.

Spanberger first won in 2018, beating the Republican incumbent by 1.9 percentage points. She was reelected in 2020 by 1.8 points. Virginia Republicans then targeted her in redistricting, making the district less familiar to her and drawing it in such a way that her home was no longer in it. Last year, she distanced herself from Biden, complaining, after Youngkin won the governor’s seat, that “no one elected [Biden] to be FDR.” Then this year, she stood up for the right to abortion and touted improvements to the district that derived from the infrastructure act. It helped her defeat her extremist MAGA opponent by 4 percent. A little FDR, she seems to have decided, wasn’t so bad after all.

This needs to be the Democrats’ message: that they are on the side of working people. They may not convince every working person, a critical mass of whom will always be drawn to Republican arguments about religion and guns and the Democrats’ alleged desire to force gender dysphoria upon the nation’s unsuspecting sixth graders. But broadcasting support for workers can draw enough voters to erase or at least mitigate the Republicans’ huge advantage among voters in America’s lower-population areas, which after all is where Democrats lose elections.

In Texas, for example, Democrat Beto O’Rourke, who lost to GOP incumbent Greg Abbott by eleven points, won just 19 of the state’s 254 counties; in many of the counties he lost, tiny as they are, O’Rourke won less than 20 percent of the vote (in some, less than 10 percent). A Democrat who could win 35 percent of that vote could win a statewide election in Texas. Demonstrating to those people that the Democrats oppose Big Pharma and the tech monopolies—and in Texas specifically, the beef monopolies—is a path to that 35 percent.

That’s a long fight—it’s a struggle to make even most Democratic elected officials understand all that, let alone voters. But there are signs that some Democrats are rising above the party’s defensive, we’re-not-too-liberal posture of the past twenty years. Fetterman, for example, probably could not have won statewide in Pennsylvania twelve or sixteen years ago. He backed Bernie Sanders in 2016 and was seen by some as “too left.” But he easily dispatched a more centrist opponent in the Democratic primary, meaning that the state’s Democratic voters judged him as electable in November. They ended up being correct. (Whereas Oz’s GOP primary opponent, Dave McCormick, was surely more electable than Oz, but he lost.)

Finally, and cheeringly, the Democrats have what the pundits call a bench, deeper than it’s been in some time, largely as a result of some crucial gubernatorial wins. Wes Moore—a Rhodes Scholar and army veteran who deployed to Afghanistan—will be Maryland’s first Black governor. Massachusetts attorney general Maura Healey will be that state’s first openly lesbian governor (the same is true of Oregon’s Tina Kotek). And in Arizona, Katie Hobbs has prevailed over the Trumpist Republican Kari Lake, giving that state its first Democratic governor since 2009.

Two governors stand out above the others. Gretchen Whitmer, of Michigan, won reelection by running skillfully on both social and economic issues; she was the candidate of abortion rights and of “fix the damn roads.” Whitmer, who emerged a sympathetic figure from a failed domestic-terror kidnapping plot against her, trounced a hard-right opponent and emerges from these midterms as a Democratic star. If Biden opts not to run for reelection, she will be an instant first-tier candidate should she choose to seek the presidency.

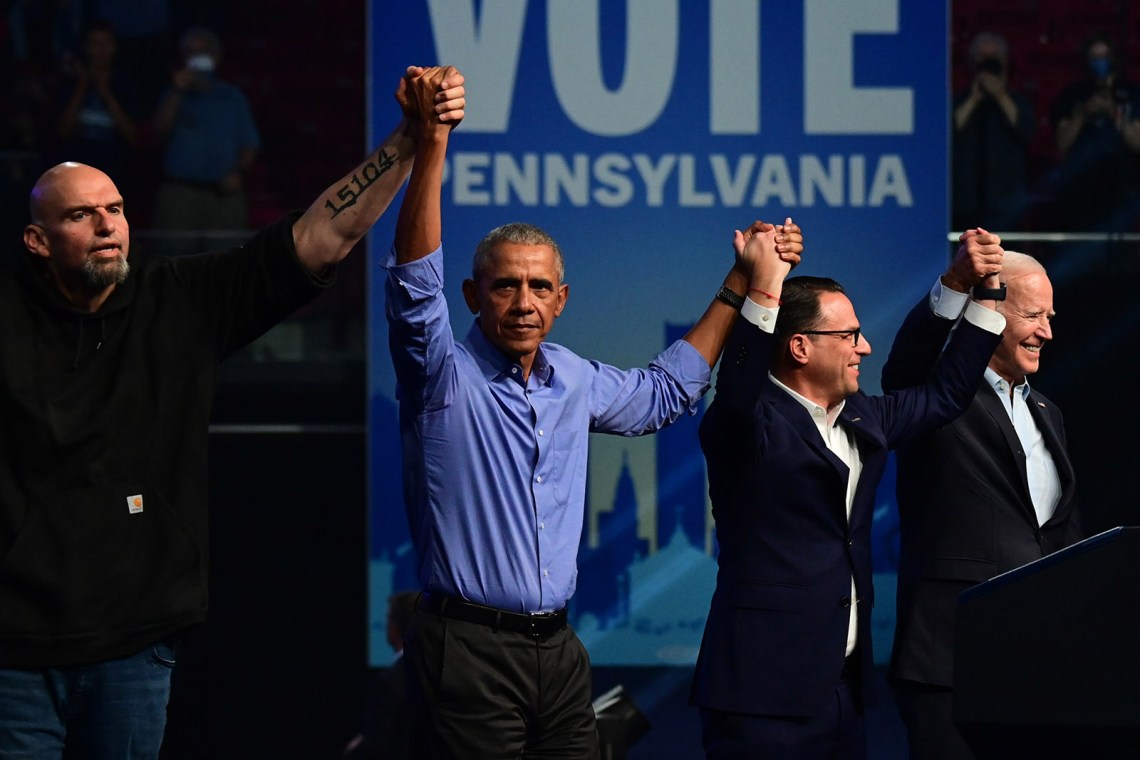

And then there is Josh Shapiro, who handily defeated the extremist Douglas Mastriano in the governor’s race in Pennsylvania. The weekend before the vote, Shapiro gave a speech at a rally headlined by Barack Obama, whose gifts for oration are known—and Shapiro stole the show. He noted, first, that Mastriano loved to carry on about “freedom,” but remarked:

It’s not freedom to tell women what they’re allowed to do with their bodies. That’s not freedom. It’s not freedom to tell our children what books they’re allowed to read. It’s not freedom when he gets to decide who you’re allowed to marry. I say love is love! It’s not freedom to say you can work a forty-hour work week, but you can’t be a member of a union. That’s not freedom. And it sure as hell isn’t freedom to say you can go vote, but he gets to pick the winner. That’s not freedom. That’s not freedom.

But you know what? You know what we’re for? We’re for real freedom. And lemme tell you what, lemme tell you what real freedom is. Real freedom is when you see that young child in North Philly and you see the potential in her, so you invest in her public school. That’s real freedom. That’s real freedom. Real freedom comes when we invest in that young child’s neighborhood to make sure it’s safe so she gets to her eighteenth birthday. That’s real freedom.

The liberal journalist Molly Jong-Fast told her one million Twitter followers, “This is an Obama-level speech.” It was, and it’s how Democrats need to think and talk.

For decades, the left has allowed the right to own the word freedom. Now—after Dobbs, and after three years of conservatives insisting that freedom included the right to cough on strangers in the grocery store—Democrats must reclaim and redefine it. If Democrats can wrest the concept away—from DeSantis’s maskless “citadel of freedom,” from the longtime proponents of the neoliberal position that the free market will free us all—and connect it to economic priorities that would lift up working people, they will be challenging a core pillar of right-wing ideology that has gone unchallenged for decades. Shapiro’s speech helped propel him to a fifteen-point victory. His party should take note.

—November 22, 2022

This Issue

December 22, 2022

Naipaul’s Unreal Africa

A Theology of the Present Moment

Making It Big

-

1

The most frightening of these is the debt limit. Economists estimate that the country will need Congress to raise the limit sometime next fall. Many political observers believe that the Freedom Caucus would rather see the United States go into default for the first time in its history than cut a deal with Biden. ↩

-

2

My recent book is called The Middle Out: The Rise of Progressive Economics and a Return to Shared Prosperity (Doubleday, 2022). The phrase “middle-out economics,” as I explain in the book, comes not from Biden but from my friends Nick Hanauer and Eric Liu, who coined it in 2011 as an answer to trickle-down economics. Trickle-down says prosperity flows from the top down and thus advocates tax cuts for the rich. Middle-out says prosperity flows from the middle and thus argues for investments (private and public) in the middle class. I and many others have been advocating for the latter for years, and it’s gratifying to see a Democratic president embracing this view. ↩