Fake pearls dangle over my unclasped breasts, so real

they hang above my waist. From time to time,

I clutch them. Mornings, I grasp for the feeling

of being touched: thumb strumming my ribcage,

fingertips smoothing my hairline. I can barely grasp

the concept of time—light given off by a cold star.

I feel naked without a watch. My father gambled

his gold watch away. I too have flung my body until,

bruised, it learned to fall. Pearl was my great-grandmother’s

name. She forbade my mother from playing cards.

The difference between a gambler and a dreamer is time.

Wanda Coleman ends “Dream 924” with the line

i did not wake up today. A line that sends the reader back

to the beginning. The tenderest touch I’ve felt

was in a dream. I couldn’t prevent my mother

from being bruised, her eye like the raccoon’s

who jostles the garbage can at night. The distance

between me and my father is frictionless, the opposite

of how a pearl comes to be. We are silver-lipped

and clammed up. An ocean, dressed in sky’s iridescence,

drifts glacially between us. I can be cold sometimes.

I’ve walked away from a lover, chest on fire, and plunged

my fists into buckets of ice. Better the burning be

mine: a flickering imitation of flame. The chill of the freezer

blew a small wind on my mother’s face. She iced her lip

and smoothed strands of her hair into place.

Twice she left my father; once she went back.

Mother-of-pearl is the name for what a pearl is made of.

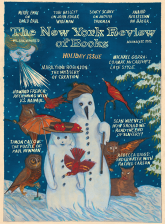

This Issue

December 22, 2022

Naipaul’s Unreal Africa

A Theology of the Present Moment

Making It Big