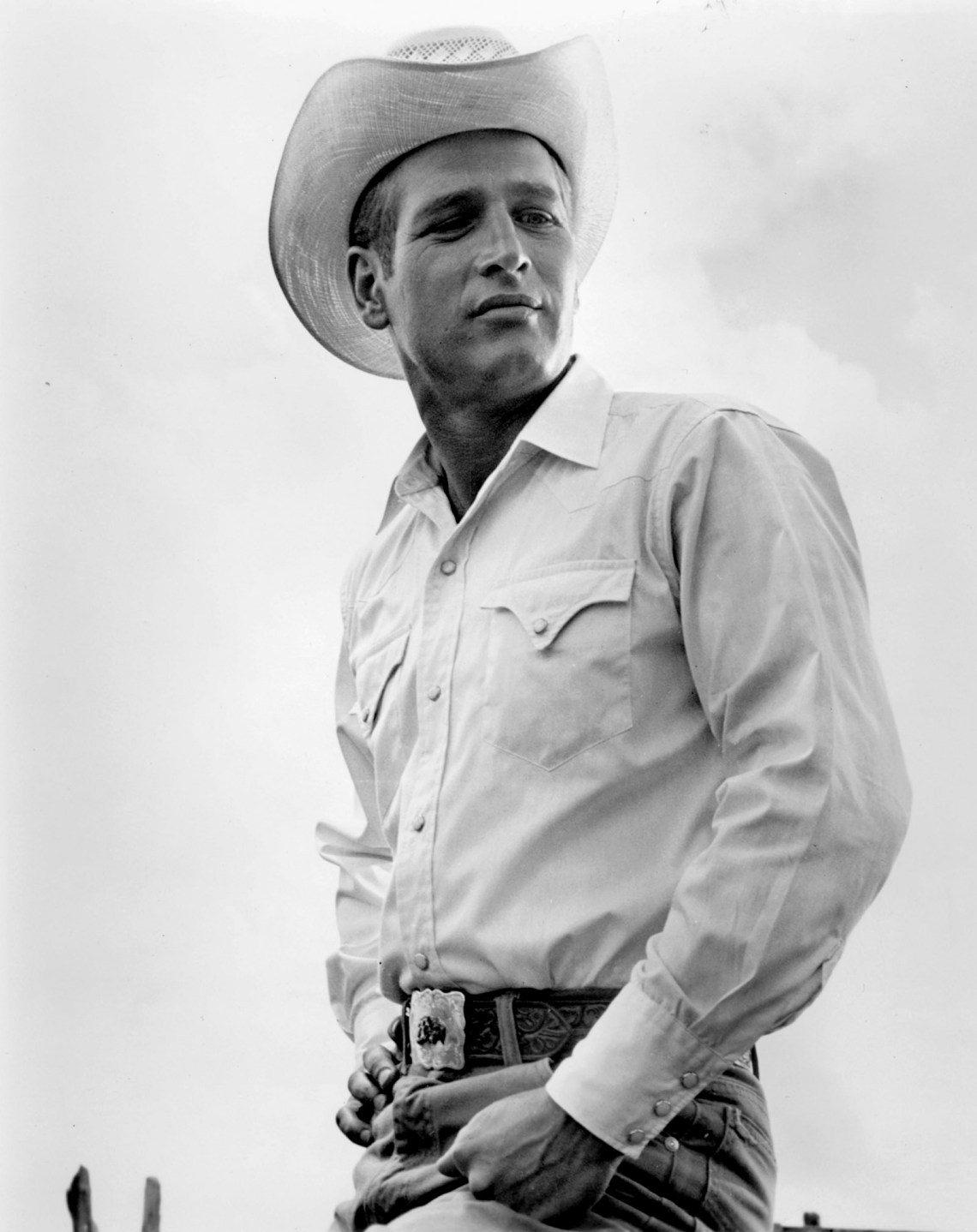

In 1989 the producer Ismail Merchant and the director James Ivory asked me, as a standing member of their informal company of players, to appear in their upcoming film, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge. Everything about the project was irresistible, not least the casting of two bona fide movie stars, Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, husband and wife, as the eponymous couple. Especially intriguing was the prospect of how they would respond to Jim and Ismail. A Merchant Ivory movie set was like no other, a curiously diffused, nonhierarchical affair, a hive of constant demented activity, punctuated with passionate cries of “Shoot, Jim, shoot!” from Ismail, while Jim quietly and methodically rearranged the cutlery. How would Newman and Woodward, accustomed to being at the top of the Hollywood pyramid, take to this democratic scrum? Perfectly well, as it turned out, but in radically different ways. She graciously introduced herself to everyone, eliciting names and facts about their lives, registering and inwardly digesting every detail. Her dressing room door was always ajar, inviting salutations and chats.

Newman, meanwhile, beat a swift retreat to his trailer, emerging from time to time to walk the dog, an elegant, long-limbed white creature whose eyes, unnervingly, were of the same piercing blue as its owner’s. The prospect of approaching this aloof duo was somewhat daunting. On the set, when Newman was separated from his dog, he was no more communicative, though he seemed to find it easy enough to talk to the crew. Normally actors on a set find a way of quickly bonding, but with him all conversational gambits resulted in rapid stalemate.

This lack of sociability extended into the filming. My first scene with Paul consisted of a card game. There were six of us around a small round table, making desultory conversation as we played our hands. The cards had to be coordinated with the dialogue, and this depended on us being able to hear one another. Paul was completely inaudible, too quiet even for the microphones to pick up. The sound crew came and asked him to speak up. He would not. Jim begged him for a decibel or two more. No way. We continued the scene, each of us trying to catch our cues. Sometimes we did, sometimes not. It was not a relaxing experience, and in the finished film half a dozen actors desperately strain to follow the conversation, which lends the scene a certain enigmatic intensity.

A month or two later I was flown to snowbound Toronto to shoot a brief sequence with Paul; there were just the two of us and a skeleton crew. We were standing only inches away from each other for the shot. Audibility was no longer an issue, but there was no improvement in human contact. We eked out a few bland exchanges in between takes and finally parted formally. The contrast with Joanne was remarkable; it was hard to know how two such antithetical figures had lived and worked together for nearly half a century. I was left bemused by the whole experience.

I understand a great deal more with the appearance of The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man, Newman’s posthumously published memoir, as vivid `an account of an actor’s inner landscape as I know. There is, of course, a long and very rich tradition of thespian autobiography, from the Elizabethan clown Will Kemp’s Kemps Nine Daies Wonder, through Colley Cibber’s eighteenth-century Apology for the Life and fascinating tomes by Beerbohm Tree, Coquelin, Ellen Terry, Pierre Brasseur, Sarah Bernhardt, Louise Brooks, Nikolai Cherkasov (Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible), and Sessue Hayakawa, whose autobiography—a particular favorite of mine—rejoices in the title Zen Showed Me the Way. Many of these books are purely commercial, nice little earners to be signed at the stage door; some aspire to being profound meditations on an art whose elements have always resisted analysis; others are confessional. In our own unbuttoned times, the steady flow of the latter has turned into something resembling a flood.

Newman’s book falls into none of these categories, since it is unclear whether it was ever intended for publication. It was embarked on as an attempt to engage with the inner dynamics of a life, on the surface hugely successful and in many ways honorable, that was a bafflement to him. At first he attempted to write an autobiography, but—highly characteristically—he scornfully dismissed his own efforts. He showed five or six pages of it to his close friend the writer A.E. Hotchner, who was encouraging, but Newman demurred: he was not, he said, “remembering the past the way he wanted to.”

He then enlisted another old friend, Stewart Stern—the screenwriter of, among many other films, Rebel Without a Cause—to interview him. And not only him but Woodward, his children, his colleagues, and his friends, dating back to his very earliest years. The project began in 1986, when he was sixty-one, the year in which The Color of Money, the highly successful sequel to The Hustler, appeared, featuring him in the role that finally won him an Oscar as Best Actor. The interviews occupied him and Stern for five years, until they finally abandoned the task. The result was, he told Hotchner, “just generalities. No substance. I read through all that and it was just a mound of Jell-O.” The tapes and the transcripts then disappeared. Newman died in 2008, apparently having given the matter no further thought; Stern died in 2015, deeply regretting their disappearance.

Advertisement

Some four years later a family friend stumbled upon more than 14,000 pages of transcripts while examining a Newman family storage unit. The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man is a skillfully edited digest of those pages. There is no way of judging how representative this selection is; what it does offer is a many-sided self-interrogation by a man who admitted to being a mystery to himself. Melissa Newman, the second of Newman and Woodward’s three daughters, professes herself, in her eloquent and candid introduction, astonished that their famously laconic father “ever considered the book you now hold in your hands.” The whole enterprise, she believes, was “an offering to the offspring…. That and maybe a way to ‘set the public record straight’ after being dogged most of his life by the tabloids.” More potently, the source of the raw power of the book is Newman’s determination to confront his troubled experience of himself—to attempt to unlock the enigma of his existence. This material has also been used in Ethan Hawke’s impassioned if perhaps somewhat overwrought recent documentary series about Newman and Woodward, provocatively entitled The Last Movie Stars.

Despite the contributions in the documentary of many of Newman’s fellow actors and the cumulative evidence of no fewer than eleven biographies—the first dating from 1975, the most lurid the swivel-eyed Paul Newman: The Man Behind the Baby Blues: His Secret Life Exposed, which purports, on the slenderest evidence, to out him as a rampant bisexual—he has always been something of a puzzle, his career path oddly fitful for someone of whom Martin Scorsese said:

The history of movies without Paul Newman? It’s unthinkable. His presence, his beauty, his physical eloquence, the emotional complexity he could conjure up and transmit through his acting in so many movies—where would we be without him?

There has always been an alternative view. The influential critic David Thomson wrote:

He seems to me an uneasy, self-regarding personality, as if handsomeness had left him guilty….

Just as his habitation of rugged “wild ones” was never totally convincing…so, too, his “straight” parts seem neutered and derivative.

For every Somebody Up There Likes Me, there was a Bang the Drum Slowly*; for every Hustler there was a Paris Blues; for every Butch Cassidy there was a Mackintosh Man—a perplexing alternation between roles in which he hits the nail on the head and those in which he seems merely in attendance, or even sometimes (as in, for example, The Outrage) almost amateurish.

Newman’s physical presence was so striking that his failures are perhaps more noticeable than other men’s: his slim, lithe physique, well into his fifties; his exceptional physiognomic symmetries; his Aegean blue eyes—all seem to promise a depth of meaning that he does not always deliver. In the early part of his career, the shadows of James Dean and Marlon Brando dogged him: he was widely perceived to lack either Dean’s alienation mingled with puppylike neediness or Brando’s anarchy, sexual danger, and unfettered imagination.

Was he an actor or a star? There is an interesting if no doubt inconclusive debate to be had concerning the distinction between the two. Crudely put, an actor does something: he or she plays a character. A star is something: in their own personas, they embody aspects of the human condition that have a deep resonance for us. This transcends interpretation; there is an ineffable something about them that for us has the ring of truth; they stir something deep within us by their very being. Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, Sean Connery, Audrey Hepburn, Tom Hanks, to name a few at random, have this quality, and we prize it highly: stars are not just for a season; they’re for life.

Despite his arresting physical attributes, Newman’s evolution into stardom was slow. After a shaky start playing the leading role in The Silver Chalice (1954), a Romans vs. early Christians film of jaw-dropping mediocrity, Newman showed that he was a contender in the Rocky Graziano biopic Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), a prentice and somewhat gauche performance but an utterly committed one, in which he reveals considerable range and an exquisite, if finally much battered, physique. What followed was less remarkable. His two Tennessee Williams films, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Sweet Bird of Youth (1962), were oddly muted, his role in the blockbuster Exodus (1960) somewhat blank. His Eddie Felson in The Hustler (1961) was a fine piece of work, sharply observed, but it was not until Hud (1963) that he emerged as a definitive presence. Martin Ritt, who directed the film, noted the precise moment it happened:

Advertisement

When we made Long, Hot Summer [1958], Paul wasn’t aware of his impact. He still looked at himself as Little Paul Newman from Shaker Heights. After Hud opened, Paul became this incredible sex object; it hit him like a ton of bricks. When we took Hud to the Venice Film Festival, we were all invited to a big reception. Though I was the director and Paul was the star, it didn’t take twenty seconds before we were separated and everyone there, man and woman alike, descended on Paul. It was entirely sexual. I was left alone standing in the corner.

Newman now knew that he had what people wanted, but he didn’t feel that he owned his natural gifts. This was the cause of a great deal of the tension in his life. He was acclaimed for an exterior that he was able to manipulate, and he became expert at calculating his effects. “How,” asked Ritt,

did Paul come to have that shambling walk, that iconic pose on all the Hud posters of him staring straight ahead, one hand on a cocked hip, the other one holding a cigarette? He actually worked all those things out by himself. These were the kind of details that he was always so concerned with in every picture he made. All I had to do was let him find it.

In these relatively early movies, the ones with which he is still most identified, there is a palpable sense of the actor’s control of himself, very different from Dean’s indulgent narcissism or Brando’s direct connection with his subconscious. Improbably, Newman compares his work to that of an accountant. “It’s possible,” he tells Stern,

for an actor to have a job that seems very glamorous to someone on the outside, and even be excited about the machinery he went through to create the part, but the work to the actor is sometimes no more interesting than the interesting parts of accounting. It’s all just a process.

His directors were often reduced to cunning and elaborate ploys to trick him into connecting with his spontaneous emotional self, and then the results are sometimes revelatory. But control is soon reasserted.

Moreover, to a degree unusual among actors, Newman was not just an actor. He had other very public identities: as a manufacturer (and creator) of a hugely popular salad dressing and a line of other food products that raised many millions of dollars for charity, as the founder and very visible supporter of a camp for children suffering from life-threatening diseases, as a fearlessly outspoken political liberal, and as a cup-winning, team-owning race car driver. All this, admirable and fascinating as it is, blurs one’s sense of Newman the actor; he was also, to complicate matters further, the director of six films (two of them very fine) as well as the producer of most of them.

During his lifetime, there were few clues as to who he really was from Newman himself, a reluctant and often capricious interviewee. “He is the most private man I’ve ever known,” said Hotchner. Perhaps because of his Garbo-like reluctance to reveal himself, his fame was immense; he was instantly recognizable. Gore Vidal, whom he had known since the early 1950s, became aware while walking down Fifth Avenue in Manhattan with him of an extremely large woman coming toward them. Newman had been keeping his head down to avoid attracting attention, but raised it for a moment. “She gave a gasp,” said Vidal, “as he looked up. We kept going and we heard a terrible sound, and Paul said, ‘My God, she’s fainted. Let’s keep moving.’”

He had an apartment in New York, but was rarely there; since 1963 he and Joanne Woodward, whom he married in 1958, rusticated themselves to Westport, Connecticut, “a woodsy exurb,” wrote John Skow in a 1982 profile in Time, “which, although prosperous and arty, had no connection to show biz.” Skow’s piece was headed “Paul Newman: Verdict on a Superstar”; the verdict is delivered by Vidal:

He has a good character, and not many people do. I think he would rather not do anything wrong, whether on a moral or an artistic level. He is what you would call a man of conscience—not necessarily of judgment, but of conscience. I don’t know any actors like that.

Newman’s daughter Susan’s judgment is less measured: “Who knows? None of us in the family has a handle on how Old Skinny Legs made it.”

The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man supplies a pretty solid handle on Old Skinny Legs and his burdensome psyche. The vast quantity of material has been superbly distilled; the contrapuntal effect of the various voices, often contradicting one another, is vibrant and illuminating. But it is Newman’s voice—angry, self-lacerating, constantly questioning—that rings out. It is for the most part a painful story he has to tell. “This book,” he says, by way of introduction,

is just the story of a little boy who became a decoration for his mother, a decoration for her house, admired for his decorative nature. If he had been an ugly child, his mother would not have given him the time of day. If he had had a limp, or an eyelid that drooped, and she stopped to comfort that small invalid beside her, it would have been to satisfy her own sense of needing to comfort something—but nothing actually to do with the boy.

The very thing that was his single most defining feature—his beauty—was in effect a scourge. He saw himself, he says, divided into decoration outside and orphan within. His early life was an unequal struggle between the orphan and “the decorative little shit” who was, as he puts it, “getting away with all the honors, doing all the plays, grabbing all the encomiums and the praise, and the orphan kept losing ground.”

This epic inner struggle was played out in the most placid of surroundings. The Newmans lived in a sort of Norman Rockwell idyll in Shaker Heights, a suburb of Cleveland. They were well-to-do; the schools were good; people were kind; nearby were acres of woods and lakes. Paul’s father Arthur and his brother ran a successful sporting goods and electronics store. A cultured, clever man, Arthur had once been the youngest reporter ever hired by the Cleveland Press. Arthur was Jewish but, writes Paul, “we were really just like anyone else.” Jewish, but not Jewish: typical of the contradictions at the center of his being. Though he always identified himself as Jewish, he had no cultural experience of Jewishness, nor did his appearance suggest it. Indeed, when he was cast in Exodus, Otto Preminger’s epic on the founding of the State of Israel, there were complaints that a gentile actor had been given the part. And it is true: had he been born not in Shaker Heights but in Germany in 1925, he would have been held up as a perfect Aryan specimen.

His formidable mother, Teresa, known as Tress, was Catholic by birth but had converted to Christian Science, having emigrated to America from Slovakia, married at sixteen, and almost immediately divorced her abusive husband. She became pregnant by Arthur Newman and then married him; Paul was the second child, and from the moment he was born, he became the focus of her life. But he had no illusions about the nature of her love:

What my mother did embrace was her own consuming passions—although never the objects that created the passion. She came to love opera, for example, and would drag me to five-hour Wagner performances at Severance Hall; the music would provoke a soaring response in her. As a child, I might do something cute or come downstairs looking especially pretty, wearing little shorts and a sweater, and she reveled in the great flood of emotion that flowed through her, whether it was tears or joy. The child himself was not really seen, just as the opera was not really heard.

This typically precise analysis describes an inner world of self-alienation, of disconnection. The language is extraordinarily powerful, even brutal:

I was like one of those poor fucking dogs of hers who became cancerous and so obese they could hardly move, and my mother would keep feeding them chocolates until she killed them with kindness. My mother was oblivious to the damage being done. Her need to bestow affection not only overwhelmed the object she bestowed affection upon, but had nothing to do with that object. My mother’s dogs were an analog to her children, to that empty decoration running around loose grabbing all the affection while his orphaned core just tried to protect himself from being crushed by the decoration. It took fifty years before the core could sit down and begin to deal with it.

According to Stern:

Paul has told me he so often feels anesthetized that he blacks out most of his childhood, doesn’t remember most of it. What he’s been looking for is the answer to the riddle of his being—why he has so much distance from his own emotions that, until recently, he could feel very, very little. A little sad, a little happy—but could never allow himself to feel all the way with either.

Something of a handicap for an aspiring actor, one might think. On the other hand, he successfully convinced his schoolmates that he was, in the words of one of them, quite frivolous: “I always felt he was very happy, with nothing to hide.” This same friend did, however, feel uncomfortable in the Newmans’ house: “There were always sheets covering the furniture in the living room—the lamps, the sofas, everything. It didn’t feel like anybody lived there.”

Paul, meanwhile, at sixteen, was

just living inside my head. I was occupied creating an imaginary, exciting world in which I was the White Knight who vanquished all enemies, a world where I was seven and a half feet tall and only did important things.

When his father told him that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, “for all that it meant to me, he might as well have said that Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse had just given birth to four dogs.” His first contact with outside reality was when he attempted to enlist but was disqualified because it turned out those baby blue eyes of his were color-blind—or seemed to be. A few months later, retested and found to have normal vision, he was duly recruited and became a gunner on a torpedo bomber plane. Short for his age—five foot five—he fell in with similarly diminutive chums, one of whom was killed on his first exercise flight. This barely penetrated Newman’s consciousness:

I remember being stunned by the news, but I somehow didn’t connect it to myself. I don’t even recall getting edgy about getting in an airplane afterwards. Back then, there must have been a strange, wonderful sense of immortality. And my own evolving type of emotional anesthesia.

It never entered my head that there was a chance we wouldn’t come back alive.

The note of self-disgust, of contempt, sounds throughout the book. It may be that he protests too much, but it is clear that this relationship to himself runs very deep—has become part of his persona.

After being discharged from the navy without experiencing combat, he enrolled at Kenyon College, having meanwhile grown a full five inches. At Kenyon he gave himself over to unbridled boozing (a commitment that endured for decades until its emotional carnage could be endured no longer). After he was thrown into the slammer for a few days for involvement in a drunken brawl, he found his way to theater. He was very successful—given good parts for which he was praised—but he never cared, he says, for the acting itself. It was the preparation he enjoyed. His greatest success at Kenyon, he says, was entrepreneurial; he created a laundry business for the students, who were lured into it by the offer of free beer: “Bring in your clothes, we’ll give you a beer.” He made a sizable sum from this; most of it he spent on booze. His contemporary Bob Connolly offers a glimpse of him:

Paul was wild, lascivious, dangerous. He was probably the most well-known guy on campus. He drank more. He screwed more. He was tough and cold—it turned on the girls. They liked him because he was the devil.

The demiurgic figure is at odds with his sense of himself and very far removed from the Paul Newman—contained, elegant, beautiful—that the world came to know so well. The book reveals his constant struggle to escape the feeling of unreality instilled in him by his overwhelming mother, who in both the photographs of her reproduced in the book wears a bright, fixed smiling mask of an expression—the struggle to feel alive. Meanwhile his father—whom he variously describes as witty, cultured, articulate—missed no opportunity to humiliate and dismiss him. In defiance of paternal stricture, on leaving college he joined a stock theater company in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, where he hooked up with a beautiful local girl, Jackie Witte, who in short order became the first Mrs. Paul Newman. Newman’s writing about this relationship is touching, tender, and for once compassionate toward his younger self:

Neither Jackie nor I had a clue of our own, not an inkling. We never thought of using contraceptives, never asked. We had no philosophy about raising kids, we’d never even had a discussion about having children or not. Things just happened because they happened….

You finished what you began.

I had no awareness that I could shape things myself.

By then his father was dying painfully of cancer, while his mother railed and screamed at him on his deathbed, convinced that he would leave everything to a nonexistent mistress or to his sons. He left it all to her. Newman bitterly regrets that his father never saw his success: “He would have honored me and recognized me.” Would he, though? Neither he nor his wife seem ever to have considered the emotional needs of their children, a lament Newman repeats over and over in the memoir. He also rues his lack of a mentor: “No scout leader or camp person. Nobody in a church. Nothing. As far as I can tell, I got no emotional support from anyone.”

His and Jackie’s son, Scott, was born around this time, a cause for joy, but qualified, in retrospect: “The connectedness was more brotherly than paternal, because I somehow didn’t think of myself as a father.” Taking advantage of his remaining discharge funds from the navy, he enrolled at Yale, but this proved only temporary relief from the encircling gloom: “I see that period in my life as the beginning of a great failure: failure to provide relief for Jackie at the home she lived in, failure as a husband, a lover, as an actor, as a father.”

It is hard at such moments in Extraordinary Life not to see the remorseful, tormented sixty-year-old sitting in front of the tape recorder as if in the confessional, his old friend nodding along sympathetically. Deeper and deeper into self-scourging he descends; his absolute lack of indulgence toward himself becomes a kind of indulgence in itself: “I don’t deny anything. I’m not trying to allay anything.” His brother, Arthur Jr., is apparently oblivious of all the inner anguish:

If Paul had accepted my advice and gone into business he still would have been successful because he was loveable, had a great personality, and made people instantly like him. Furthermore, he was smart and he was perceptive and he had all the ingredients no matter what he did.

At Yale Newman decided to major in directing: “I was convinced the nameplate that said ‘Director’ on your door was better than one that said ‘Actor.’… I had no real plan; but with directing, what I had was a parachute.” Arthur Newman was still calling the shots from beyond the grave.

Newman likes to imply that he simply drifted into acting; the memoir calls him out on this. In due course he was given the plum role of Karl, Beethoven’s nephew, in a student play about the composer. “Was it luck he got the part in Beethoven?” asks his classmate Anne Knoll Nixon. “No. He got Beethoven because he made sure he got it.” He was evidently not quite the naïf he liked to think he was. But though warmly appreciated, both as an actor and as a drinking companion, he found it hard to believe in himself as the person he wanted to be:

The innovator, a person who discovered things, new modes and new styles. I never felt that. I never had a sense of talent because I was always a follower, following someone else with stuff that I basically interpreted and did not really create.

Again and again through the book, this altogether exceptional individual, so striking both in his looks and in the force of his personality, confesses to feeling unremarkable—ordinary, as the title has it. Perhaps stuck or frozen might better describe his inner state—or wooden, like Pinocchio. When Newman later went to classes at the Actors Studio, he was too inhibited to stand up and do an exercise, but he keenly watched these highly successful actors going through their paces, learning, as he puts it, by osmosis.

Others saw him quite differently at that age. Only three months after leaving Yale, he got a small part and was understudying another in William Inge’s new Broadway play, Picnic. He was so good as the understudy that the director, the famous Joshua Logan, sacked the actor Newman was covering and gave him the part, which Inge thereupon rewrote for him. “He immediately fell into the part of the rich boy, and made the play stronger,” says Logan. “In fact, it was Paul who made the play a hit.” Later that same year, the influential Theatre World anthology nominated him as “one of the most promising personalities of the year.” Logan had meanwhile appointed him understudy to the leading character. When that actor went on vacation, Newman asked the director to let him take over the part. “I’d like to, kid,” said Logan, “but you don’t have any sex threat.” So much for the lothario of the campus.

It was Joanne Woodward, also an understudy on Picnic, who liberated his dormant sexuality:

Joanne gave birth to a sexual creature. She taught him, she encouraged him, she delighted in the experimental. I was in pursuit of lust. I’m simply a creature of her invention….

All my desperate fantasies and years of being turned down disappeared with Joanne. I suddenly found the door of opportunity flung open right before my eyes. Joanne made me feel sexy.

He identified her as another orphan, and

orphans do have big appetites…. We made a point during Picnic and afterwards to let the lusty aspects of ourselves have time to function without interruption or distraction; I think we were pretty good about that, we left a trail of lust all over the place. Hotels and motels and public parks and bathrooms and swimming pools and ocean beaches and rumble seats and Hertz rental cars.

He would cling to his marriage (he and Jackie had three children) for five years, but the magnetic pull toward Woodward was irresistible; finally they were officially together, and remained so for fifty years. He meanwhile got his first break in film, The Silver Chalice. He was painfully aware that he had been offered the part simply because of his looks. “There’s something very corrupting about being an actor,” he said in an interview. “It places a terrible premium on appearance.”

For many actors, the experience of acting is liberating, the joy of being someone else, of feeling the muscles in the face and the body spontaneously rearranging themselves under the influence of an image or a sensation. This seems never to have happened for Newman. Clearly part of him needed to cling to the mask: it was, after all, and certainly at the beginning of his career on film, the source of his employability. And as his biographer Daniel O’Brien tartly remarks:

For all Newman’s ambivalence towards his looks, he’s nevertheless worked long and hard to preserve them. For most of his career, Newman routinely employed Murine drops prior to public appearances. His daily saunas and three-mile runs kept him in great shape despite a prodigious beer intake. He also had a phase of soaking his face in ice water to keep those jowls firm.

“Where the hell would I have been if I looked like Golda Meir?” says Newman to Stern. “Probably no place; it was like being a guy with a trust fund who doesn’t have to work. I always had that trust fund of appearance. I could get by on that. But I realized that to survive, I needed something else.”

But at the beginning of his screen career, it simply made him feel uncomfortable. “I don’t think Paul Newman really thinks he is Paul Newman in his head,” remarked William Goldman. We rarely talk or write about male beauty; it makes us uncomfortable. Patricia Neal, quoted in the memoir, is uncommonly direct about it: “All of a sudden here was this fabulous boy…. I mean, he was staggering. That was my first impression of Paul Newman: the beauty of the world.” But for Newman it was a visor, a mask impossible to prize off, charming and delighting the world but creating a block between him and it.

As he proceeded through his career, he attempted to vary his appearance, his physical life. Sometimes these attempts misfired, as in The Outrage (1964), in which he plays a Mexican bandido: “He was an absolute primitive, which I had never played, with an entirely different sense of movement and an accent I wasn’t familiar with…I did it because I didn’t think I could do it.” O’Brien observes:

Outfitted with…contact lenses, black wig and moustache, and heavy stubble, Newman certainly looks distinctive…. For all the in-depth research, his growling bandit is a parodic Mexican, complete with sombrero and poncho.

His great roles left his features untrammeled, offering variations on a theme and endearing him to the public: characters John Skow in his Time profile well describes as miscreants who are “not just part of our culture now but almost part of our national character: the hero as romantic screwup, the loner crabbed by society and usually, despite his looks, not very lucky with women.” What finally changed for him was aging. To the end, even in his eighties, he remained strikingly handsome, but from the early 1980s natural attrition began to humanize his features, wore away the sheen, and finally liberated him from the mask of beauty.

His life had much earlier expanded into other dimensions: in the early 1960s he, along with Marlon Brando and Burt Lancaster, came out in support of the civil rights movement, eloquently answering his critics: “Am I any less a citizen for being an actor?… How can we question the immorality of other nations when we have this blight of Negro inequality hanging over us?” After Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, he, Barbra Streisand, and Brando pledged one percent of their income to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; Newman sat on the advisory board of the American Civil Liberties Union. By the late 1960s, he was beginning to express dissatisfaction with acting:

It’s all pretty familiar. The more I do, the more I duplicate. I’m not inexhaustible, like an Olivier. I don’t have that kind of talent…because acting comes to me very easily…it is very difficult for me to comprehend why the rewards for doing something that doesn’t really seem to involve that much work should be so extraordinary.

He started directing, initially to boost Woodward’s career in movies. The relative eclipse of her career by his was a source of deep guilt to him. Martin Ritt, the director of the first film in which they appeared together, said categorically, “She was a much better actor [than him] when we made Long, Hot Summer; they were not comparable. Joanne was as good an actress as existed at the time.” Despite her ever-growing mastery, she never became a star; Newman did everything he could to make her one. His debut as a director, Rachel, Rachel (1968), won her an Oscar nomination and him many plaudits. “In many ways, Paul’s best acting performance was as the director of Rachel, Rachel,” remarked Frank Corsaro, the stage director and later the head of the Actors Studio.

I’ve never seen so much finesse, his extraordinary sensitivity came through. He was able to coalesce some of his most tender feelings and allow them expression through the film’s actors….

Paul made very specific demands on the cast in areas of feeling and playfulness that very often were missing in his own work as an actor.

The memoir as edited rarely pulls its punches. “The reason I’m surprised Paul doesn’t direct more,” said the director Sidney Lumet,

is that it seems a great solution for him. If one is afraid of exposing one’s vulnerability to the masses, it’s clearly easier to confine the exposure to the very intimate circumstances of actors whom you’d get to know well during the process of directing them.

None of the other films he directed quite succeeded in the way Rachel, Rachel had, even when Woodward was in them.

Inspired by his unlikely friendship with Gore Vidal—“I was always a bit concerned that I was difficult to talk with because I wasn’t educated in the same way as Gore and his guests”—Newman continued to be active politically, backing Eugene McCarthy in his campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968. Five years earlier, he had gone down to Gadsden, Alabama, with Brando and others to support the black community there. Discovering that the police routinely corralled activists there with cattle prods, he asked one to allow him to experience it:

And with that, he touched it to the muscle that runs down along my backbone and I jumped about ten feet across the room. It had an incredible jolt, and all I could imagine was what would happen if someone got shocked in their chest or stomach.

Characteristically he doubts whether there were any tangible results from their visit.

Disillusioned with politics, he increasingly involved himself in charity, harnessing his name and fame notably in the phenomenal success of the Newman’s Own line of salad dressings and other food products, beginning in 1982. “One of the advantages of being Paul Newman,” wrote Hotchner, his partner in the business, “was the power that his name commanded. ‘Paul Newman calling’ dissolved barriers, brought down the walls of Jericho.” Despite being warned that the start-up loss for most celebrity products was somewhere close to $1 million, Newman and Hotchner pressed on with it; by May 2021 Newman’s Own had disbursed $570 million to charity. His father’s gift for salesmanship—and his own entrepreneurial instincts, as demonstrated in his student laundry-and-beer venture—asserted itself; it seemed more straightforward than the uncertain business of making movies.

It was the same with the Hole in the Wall Gang program—named after the legendary gang in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)—an idea that came to him during the unhappy experience of editing his film Harry and Son (1984), which he directed and in which he appeared; he denied that the film was in any way connected to the death from drug-related causes of his son Scott, but something must have impelled his single-minded dedication to creating a haven for seriously ill children. He raised phenomenal sums from wealthy donors, notably August Busch, the owner of Budweiser. “August,” he said, “I want you to be responsible for the crown jewel of our camp, the mess hall.” “How much do you want?” “I need $866,000. And we’ll match it.” “Deal.” The transaction took about eight minutes. He puts it all down to what he frequently refers to as “Newman’s luck.”

Perhaps. It’s nonetheless a deeply heartening story. How many other similarly privileged people could have done this and didn’t? Or don’t. It was also, of course, self-healing. Tormented by his own failures as a parent, above all the death of his son, he focused on tragically afflicted children. As a philanthropist he was able to believe in himself, because the end was more important than him or his private doubts. It mattered. And that somehow is very elusive for certain actors: the sense that acting really matters.

Newman wrote a thank-you letter to Busch that is entirely characteristic in its wit, its self-denigration, and its rough charm:

In all the years since I was in the Navy, starting at age eighteen, I have consumed approximately two hundred thousand cans of Budweiser beer. So, if you really look closely at the figures, your contribution comes to just about a four-dollars-a-bottle rebate. And since you’ve had use of the money since 1944, it isn’t really all that much. Still, I’m grateful.

Newman’s drinking was indeed on a titanic scale, to the degree that one wonders how he was able to function at all. He was not a nice drunk, either, as his agent and later producing partner John Foreman attests:

Many times as he got drunker, it was nice, but many nights would take a turn and Paul would get exceedingly ugly and bad. He often talked about “the click,’’ and suddenly all you’d hear would be “cocksucker” this or “fucking” that. He’d attack the business, everything he had done, all his work, his failures as a husband and as a father, on and on until finally, he’d just be making slurred animal noises…or call me dirty names or tell me how much he hated me.

Finally Woodward called him on it, and he weaned himself first off spirits, then beer, and finally wine, until, as she said, the nightly glass he poured himself was merely a pacifier. The booze was, as it so often is, an escape from reality that ended up taking him ever deeper into the reality he wanted to avoid.

There is a curious sense throughout the memoir of Newman having chosen the wrong career. He was always, at least until his sixties, uncomfortable with acting, the demands it made of him, the self-examination and self-exposure required, just as he was uncomfortable with being a father and even a husband. Confronted with the demands all of these things make on him, feeling inadequate to them, he falters, runs away, gets drunk, then imposes an iron discipline on himself that enables him to function remarkably well but brings its own cost. With racing and philanthropy, the end is so much simpler; he knows what to do, and he does it. “One of the things that first drew me to auto racing,” he says, “was that it is so nice and clean about the results. If you come across the finish line first, you’re first.”

His breakthrough into a different level of acting may have been connected, as his fellow actor Milo O’Shea thought, with the death of Scott, confronting which, says O’Shea, seems to have helped him feel his way “into a deeper part of himself, to a layer that has never been exposed before,” finally able to transcend the mask fixed on him by his mother, not merely, as in Hombre (1967), to fix another mask on top of the first mask. His performance in Nobody’s Fool (1994) as Sully—“a good-natured loser with poor employment prospects and a bad knee…a gambler, petty thief and dog doper,” according to O’Brien—who struggles to deal with an estranged son and a drunken dead father, seems to confront everything that he was unable to face in Harry and Son. Finally, in Road to Perdition (2002), the very last film in which he appeared, his sharply etched, tightly contained performance elicited the following encomium from the formerly hostile Thomson: “All of a sudden, very late in life, Newman has become a wonderful actor.”

He even returned to the stage, to act on Broadway in Our Town as the Stage Manager; his program note was as wry as ever: “Best known for his spectacularly successful food conglomerate…. Purely by accident has done 51 films and four Broadway plays.” To his legacy as actor, philanthropist, and race car driver must now be added this memoir. As an account of the inner life and struggles of an altogether exceptional human being, it belongs with the best of memoirs, theatrical or otherwise. The only quibble might be with the title: there was nothing in the least ordinary about Paul Newman. He faced his final illness from cancer with great courage, wit, and dignity. His last words to his old friend Hotchner, a reference to racing, where he claimed to have found his deepest ease with himself, were: “I’m running out of gas…it’s been a hell of a ride.”

As a postscript to my own uncomfortable encounter with him on Mr. and Mrs. Bridge, I was astounded when I saw the finished film. Underneath the impeccable period detail, Ivory’s directorial work is ruthlessly unsparing. Woodward’s performance is unspeakably moving, revealing a deeply unhappy woman whose happiness could so easily have been secured by the simplest of tokens of affection—tokens that Walter Bridge refuses, on principle, to give. As for Newman, his portrayal of emotional withholding at the center of the relationship is painfully honest and unerringly achieved. Newman reported that Woodward thought his Mr. Bridge was a self-portrait; he denied this, but it is clearly informed by the same unsparing self-disgust that is so painfully on display in the memoir. Either way, it is unquestionably great acting.

This Issue

December 22, 2022

Naipaul’s Unreal Africa

A Theology of the Present Moment

Making It Big

-

*

The television play broadcast in 1956, not the 1973 film. ↩