If eros, as Freud believed, is what binds us to the world, creating ever-larger units of society, economics could be seen as the child of eros. So it has been at least since the eighteenth century, when “commerce” and “intercourse” began to be used interchangeably and the modern idea of the economy was born in the writings of philosophers such as Adam Smith, whom I discussed in the first of these articles.1 Hume saw merchants and money as the instruments of an expansive and intimate contact among peoples from afar. Marx and Engels marveled at how the mass commodities of capitalism, along with its “immensely facilitated means of communication,” drew the nations of the world into a global civilization. Even the ancient Greeks, who sought to restrict the economy to the needs and activities of the household, felt the outward pull of trade. So powerful was its draw that Plato feared it might lead the city, like a lusty teen, to open its arms to “diverse and low habits” from abroad. The only reliable prophylactic was to site the city nine miles from the sea.

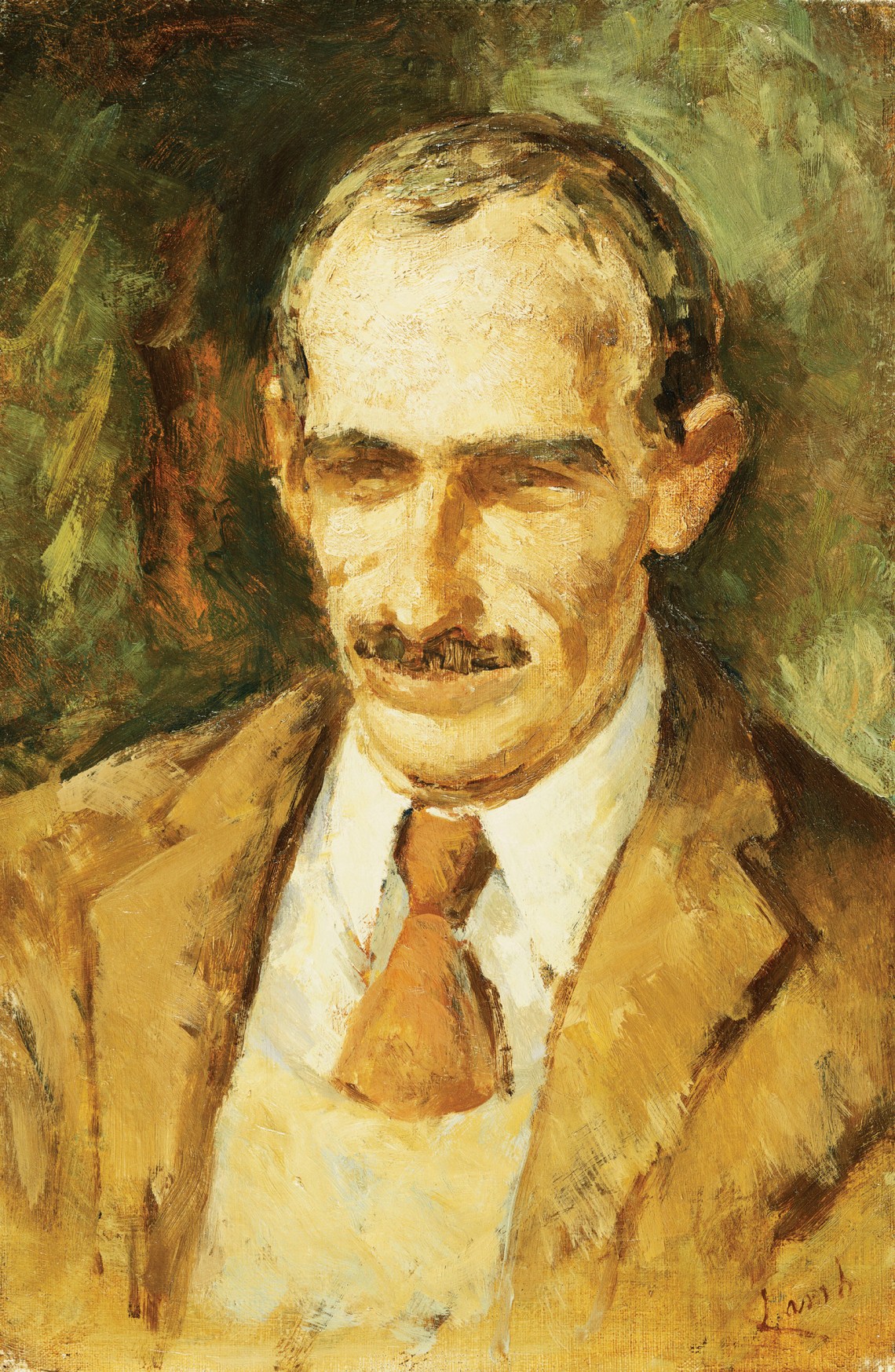

John Maynard Keynes was born into this inheritance, which he described in loving and gently ironic detail in the opening pages of The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), his scorching criticism of the Treaty of Versailles. Europe in the late nineteenth century was an “economic Eldorado” where the “internationalization” of “social and economic life” was “nearly complete.” Labor was on the move, emigrating to far-off lands, building transportation systems to carry goods and people more easily across the globe. Capital and consumption were cosmopolitan. “The inhabitant of London,” Keynes wrote, “could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep.” The man in London followed the world’s goings-on, whether near or far, and traveled everywhere he could. He was a lot like Keynes, Zachary Carter shows in The Price of Peace, his delightful and penetrating biography of the economist and his afterlives. Keynes toured the Continent, hoping that the “world of art, beauty, and cross-cultural understanding” that he and his wife, Lydia, a Russian ballerina, had created in London could be reproduced elsewhere—if only the right economic arrangements were made.

But, Keynes wondered, what if that man and that world were disappearing? In the twentieth century, it seemed that the most common act of Homo economicus was not intercourse but “abstinence,” a word that reverberates across Keynes’s writings. Most of the time the man in London hid at home, holding on to his money. This was not an entirely new development. As Keynes points out in his essay on Thomas Malthus, capital’s withdrawal from the economy was a problem in the early nineteenth century as well. But it had ceased to be a temporary malady of individuals only. Entire cities, states, and societies now associated the word “economy” with “the negative act of withholding expenditure.” Instead of creating wealth, acts of economy yielded waste—unused materials, unemployed labor, empty factories. No longer the child of eros, economics had become a shepherd of death. Keynes set out to discover why.

Joseph Schumpeter claimed that the work of the economist has two elements. There is the “vision,” what the economist sees as “the basic features of the state of society, about what is and what is not important in order to understand its life at a given time.” And there is the technique, “an apparatus by which he conceptualizes his vision and which turns the latter into concrete propositions or ‘theories.’” Every economic theory, in other words, is the condensation of a larger social vision. Though scholars in the humanities have long known this of Smith and Marx, they tread more carefully around Keynes. The warrens in his prose can be forbidding, the equations out of reach. With a few exceptions, he has been left to the economists and the economics-adjacent to interpret and make use of.

Carter shows how mistaken that avoidance is. His Keynes belongs alongside Aristotle, Machiavelli, and Burke. Providing supple analyses of Keynes’s economic claims, Carter restores the worlds—Cambridge philosophy and morals, Bloomsbury aesthetics, and Whitehall politics—that are embedded in them. While Robert Skidelsky’s three-volume biography remains the touchstone for a full account of Keynes’s life and thought, Carter’s brings the thought to life in a way that is truer to the man. The “master-economist,” wrote Keynes, “must be mathematician, historian, statesman, philosopher,” dealing in “the temporal and the eternal, at the same time.” That is the Keynes Carter gives us.

According to Carter, Keynes was to Adam Smith “as Copernicus was to Ptolemy—a thinker who replaced one paradigm with another.” Yet of all the economists who came after Smith, none was caught by his vision more than Keynes. Like Smith, Keynes imagined economic action not simply as a path to wealth and plenty but as a movement toward others. At the conclusion of his analysis of the Treaty of Versailles, which he opposed because it imposed a “Carthaginian Peace” on Germany at the expense of building a true union of Europe, he issued a plea: “Even if there is no moral solidarity between the nearly-related races of Europe, there is an economic solidarity which we cannot disregard.” That economic solidarity could pave the way to moral solidarity. Like Smith, however, Keynes was struck by how easy it is for people to disregard economic solidarity, how little empathy and outwardness there is in the economy.

Advertisement

The great set pieces of Keynesian economics are sketches of failed connection. Where Smith’s Wealth of Nations begins with stories of people finding one another through labor, Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) opens in a fog of mass joblessness. Despite the forces of supply and demand being in balance, entire swaths of the population are unemployed, not contingently but structurally.

Keynes’s prolegomenon points to a problem that is both empirical—Britain and other countries have just come through one of the worst unemployment crises in decades—and theoretical. The pairing of systemic unemployment and equilibrium would have been inconceivable to Smith, who believed that the laborer “supports the whole frame of society” and “bears on his shoulders the whole of mankind.”2 It wasn’t possible to have a properly functioning economy without everyone’s having (or being on their way to having) the means to support themselves and their families. That is why Smith could declare with such confidence that the well-being of the lowest laborer is the moral measure of an economy’s worth. Yet in Keynes’s world, the economy was in equilibrium while a large stratum of workers was idle, not because they had been displaced by machines or refused to work but because equilibrium could be achieved without them. This was “the most shocking view in The General Theory,” the Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson later wrote.

Previous economists had assumed the truth of Say’s Law, which Keynes glossed as “supply creates its own demand.” Whenever goods are produced or services are furnished, payments are made to the workers, landlords, creditors, and entrepreneurs who supply the requisite labor, land, credit, materials, and so on. These incomes, earned from individuals’ contributions to the production of goods and services, generate sufficient demand to ensure that those goods and services find buyers. The higher the output or supply, the greater the income or demand. As a result, the economy always tends toward full employment.

What if it doesn’t? Instead of spending their entire earnings on goods and services, workers might hold some back. Instead of pouring their profits into expanded production and investment in new technologies, entrepreneurs and creditors might keep those profits for themselves. Abstinence on a mass scale would leave the economy at levels of output so low that society couldn’t provide jobs for everyone; the loss and the waste would be catastrophic and cruel. Understanding this problem of “effective demand”—the fact that demand can match supply at dangerously low levels of activity—is for Keynes “the beginning of systematic economic thinking.”

Much of Keynes’s economics, like Smith’s, is a sustained exercise in empathy-building, attempting to create on paper the solidarity that has failed to materialize in practice. But where Smith thought there were forms of self-interested, profit-driven action that would gradually orient the self to the other, Keynes could not take that orientation for granted. In “modern conditions,” he wrote, the individualism of the Smithian economy was at best no longer applicable and at worst a “mortal disease.” A path that works for me when I take it alone may work against me if everyone takes it, too. The modern economy is littered with examples of this, yet knowledge of the social dimension of economic action—that we do not choose alone, that our actions have effects on others—has not yet penetrated our decisions in the market. The task of the economist is to create the social knowledge of the other that Smith hoped would arise from the act of seeking profit for oneself.

In his first such foray, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Keynes used economics to show how debt sows division and conflict while forgiveness of debt nurtures connection and amity. At Versailles, the Allies levied heavy reparations on Germany as punishment for its actions in World War I. Decimated by the war, Germany lacked the cash reserves to pay the reparations. The only way it could build those reserves was through trade—by exporting more than it imported.

Advertisement

But Germany was a net importer, relying on imports to feed itself and for the raw materials it needed for industry. To become a net exporter, it would have to scale back its consumption to the bare minimum and limit imports of the very materials it needed to manufacture goods for export. Even if it could be forced to hand over its entire surplus while subsisting on a starvation diet—a regime of servitude and extraction, Keynes notes without irony, that the “white race” was unaccustomed to—Britain would be compromised by such a regime, since its economy depended on the export of manufactured goods, including to Germany. What would happen to British trade if Germany were transformed into a net exporter of the same goods?

Keynes thought that the Allies’ approach to reparations reflected an inability to appreciate the social dimension of debt, which only the economist could remedy. They viewed reparations “as a problem of theology, of politics…from every point of view except that of the economic future of the States whose destiny they were handling.” Looking at debt through a prism of guilt and responsibility, politicians and theologians isolate the debtor in a cell of judgment and punishment, rendering her incapable of acting upon the society that is acting upon her.

The economist helps us see that debtors cannot be sequestered from the rest of society. Debt is the sibling of credit, a lubricant of trade and commerce, “the ultimate foundation of capitalism.” Whatever is done to debtors will come back to haunt everyone else. “We shall never be able to move again, unless we can free our limbs from these paper shackles,” Keynes writes. The only way to start the economy, to make it move, is to light “a general bonfire” of those shackles and forgive all debts.

In politics, Walter Benjamin wrote, “it is not private thinking but…the art of thinking in other people’s heads that is decisive.” The power of Keynes’s economics is that it assigns that art of public thinking not to the statesman or citizen but to the economist and to ordinary economic actors. This was increasingly true of Keynes’s work throughout the 1920s and 1930s, culminating in the climactic passages in The General Theory where he addresses the relationship between saving and spending, investment and enterprise.

Traditionally, economists had seen the individual’s decision to save as the condition of capital accumulation and economic expansion. “Parsimony, by increasing the fund which is destined for the maintenance of productive hands, tends to increase the number of those hands,” wrote Smith. “It puts into motion an additional quantity of industry, which gives an additional value to the annual produce” of a country’s economy. Saving is a form of investment, not just for the individual but for society.

This claim, Keynes counseled, reflects a one-sided view of the matter, the view of the saver in solitude. It’s true that the individual who limits her consumption for five years to save money for a home renovation is making an investment in her future. It’s also true that her restriction of consumption will have a negative impact on other people’s incomes in the intervening years. Think of the restaurants she won’t frequent, the books she won’t buy, and so on. That diminution in the incomes of the restaurants and bookstore owners will have a negative impact on their spending and savings and still others’ spending and savings. One person’s savings, if aggregated, can lead to a decline in social wealth:

Suppose we were to stop spending our incomes altogether, and were to save the lot. Why, every one would be out of work. And before long we should have no incomes to spend. No one would be a penny the richer, and the end would be that we should all starve to death.

The view from both sides is not reserved to the economist or the policymaker. Keynes wanted it to shape the mind of the individual as well. Go shopping, he told the “patriotic housewives” of Britain in 1931, “and have the added joy that you are increasing employment, adding to the wealth of the country,” and “bringing a chance and a hope to Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Belfast.”

As much as Keynes worried about the withdrawal of the self and its failure to connect with the other, so was he plagued by the Smithian problem of lookism: how we overconnect with others, outsourcing our judgments to them. Nowhere was this clearer than in the stock market, which Keynes believed had become one of the main drivers of investment and the economy. Before there were stock markets, a businessman and his family or friends pooled their money and invested it in an enterprise for the long term. Uncertain when precisely their investment would pay off, they simply expected a yield at some point in the future. With the rise of stock markets in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, owners are separated from managers, and investors are freed from the ball and chain of a personal enterprise or family firm. Their decisions are increasingly determined by their “fetish of liquidity”: their preference for assets that can be gotten into and out of quickly. They don’t care whether a stock certificate is tied to an enterprise that will turn a profit in the decades to come; they want to know how the market will value the stock a few months or days hence. They absorb themselves in looking at others for clues as to whether they should buy or sell.

The result is a perverse sort of beauty contest in which none of us chooses our favorite contestant but the one we think others are likely to choose. Instead of the equilibrium of self and other that is Smith’s communion of needs, Keynes writes,

we have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.

With each calculation, with each degree, we drift further and further from ourselves.

It’s no accident that Keynes landed on this image of a beauty pageant to illustrate the fate of the self in the market. This was the world that Smith, under the influence of Rousseau, feared the market would reproduce. Rousseau believed that a fateful turn in human development occurred when we gathered in front of huts and under trees to perform for one another. Before that, each of us was confined to the little society of the family, tending to our needs (not unlike Keynes’s idea of the investor tied to a family firm, before the advent of the stock market). But when we began to perform for one another, “everyone began to look at everyone else.” A new self was born, the self who lives “outside himself.” Increasingly concerned with our opinions of others and others’ opinions of us—what Rousseau called the price of esteem—this new self could be found wandering around the courts of the old regime or among the stalls of the new markets that were coming into being. If one pathology of the market was the failure to connect, the other was the failure to disconnect.

The question for Keynes was: How and why does the economy spur these twin pathologies? The answer, he came to believe, lies in two elements of economic activity that previous economists had ignored or assumed to be benign: money and time.3

Economic theorists often begin with barter as the archetypal economic activity and scale up their visions of the economy from there. That beginning, Keynes thought, colors all their endings. What distinguishes barter is its physical and temporal immediacy: two individuals, present to each other, trade material objects for direct use. Even if money is introduced into the exchange, the immediacy remains. Money is only a “transitory and neutral” medium in these cases, a “mere link between cloth and wheat.” The “essential nature of the transaction” is “between real things.” Such an economy is a “real-exchange economy.” In a modern or “monetary economy,” by contrast, money ceases to be “transitory and neutral in its effect.” It becomes “one of the operative factors” in the transaction, shaping our motives and influencing our decisions. According to Keynes, this is what previous economists have not realized.

What turns money from a neutral instrument into an active force is time. “In a world in which economic goods [are] necessarily consumed within a short interval of their being produced,” money has little effect. Even if its value fluctuates—a feature of economic life that economists before Keynes were certainly aware of—the distance in time between the moment of purchase and the moment of use is not large enough to affect our decision to act now as opposed to later. But “the whole object of the accumulation of Wealth,” which drives the modern economy, “is to produce results, or potential results, at a comparatively distant, and sometimes at an indefinitely distant, date.”

With that increase in temporal distance and the introduction of the far-off future as a factor in our calculations, money becomes a more potent concern. A monetary economy is not simply an economy in which money is a factor of exchange. It is an economy “in which changing views about the future are capable of influencing,” via money, the overall output of the economy. Because we have little certainty about what the future will bring, we fall back on a convention, a socially approved way of thinking about the future that “saves our faces as rational, economic men.” One of those conventions is that our opinions of the present are a useful guide to the future. Another convention is that prices in the present contain reliable information about the future or at least how people are thinking about the future. We have no rational basis for either of these beliefs. The future can never be gleaned with certainty from the present. But these conventions have the sanction of our peers, and comporting with their opinion is another convention. It is not simply the stock market, in other words, that turns us into the outsourced selves of the beauty contest. Many economic decisions in a monetary economy press us to cede our personal judgments and allow others to do the judging for us.

At certain moments, particularly of crisis or change, the uncertainty of the future is revealed and the flimsiness of these conventions is exposed. The quiet precarity of our judgment gives way to a roaring river of anxiety. Then something peculiar happens to money. We stop using it as a medium of exchange in the present. We grab hold of it as a “store of wealth” accumulated in the past that will protect us from the future. Money now seems objective, certain, and secure, the one form of wealth that will not erode or disappear over time. Holding on to it “lulls our disquietude.” This is true whether it takes the form of gold, silver, paper, or electronic bank records. Nor can the problem of money be solved by eliminating these forms: “So long as there exists any durable asset, it is capable of possessing monetary attributes and, therefore, of giving rise to the characteristic problems of a monetary economy.” Instead of opening a sluice through which trade can flow, instead of serving as a medium of movement, money becomes a source of stasis. It produces the abstinence that Keynes thought was the blight of his era.

This analysis of the toxic synergy between money and time is easily the most influential and familiar of Keynes’s arguments. But he also makes a second, more radical claim about money and time, which hearkens back to an ancient leeriness, extending from Aristotle through Marx, of the abstraction that lies in wait for all economic activity. Keynes believes that there is something about our imagination of the future, quite apart from its uncertainty or our anxiety, that makes it vulnerable to the lure of money. Economic decisions often entail a present sacrifice—an exertion of unwelcome effort, a surrender of time or resources—for future gain. Once we determine where the greater magnitude lies, with the sacrifice or the gain, we can decide whether or not to move forward with the choice. But when money is the measure of the magnitude of our loss and gain, it obscures the “concrete goods” that are to be lost or gained. We simply lack the “strength of imagination” to resist thinking in “money values” as opposed to “real values.” We also don’t have the imaginative power to translate money values back into real values. “Abstract money overweighs” every step in the calculus. We find ourselves “making unreal decisions all the time,” unable to keep in mind our goals and the relationship between goods and goals, and thus whether the sacrifice is worth it or not.

The reason money is not a neutral instrument of exchange, then, is not simply that it is a hedge against uncertainty or a salve for anxiety or that we live in an economy of booms and busts. It’s that money becomes more real than the concrete goods we are giving up or in quest of. Forgetting that money is “a means to the enjoyments and realities of life,” not an end, we abandon the reality of the present for the fiction of the future. The person who thinks in money

does not love his cat, but his cat’s kittens; nor, in truth, the kittens, but only the kittens’ kittens, and so on forward for ever to the end of cat-dom. For him jam is not jam unless it is a case of jam tomorrow and never jam today. Thus by pushing his jam always forward into the future, he strives to secure for his act of boiling it an immortality.

The danger of money is not that it is abstract, but that it abstracts us. It removes us from the here and now and throws us to that “spurious and delusive immortality” that lies beyond.

Hume had taught that money is more than a lubricant of exchange; it is a conjugate of social life. Without money, the goods we produce remain at home for consumption or travel no further than the local market. Without money, we are kept provincial. When money becomes the medium of exchange, goods can travel further, penetrating distant markets and influencing the manners and mores that reside within those markets. We are deprovincialized, opened to the stranger, and made larger and less familiar to ourselves. Money is a vector of cosmopolitanism.

Keynes, on the other hand, believed that “the importance of money essentially flows from its being a link between the present and the future.” Behind “the veil of money,” the only self we can link to is the abstraction of a future self. The connection between our present and future selves is so charged that we cannot break its hold; we cannot connect with other people. Not only does money fail to fulfill the cosmopolitan purpose Hume thought it would; it obstructs the worldliness that other economists thought the economy would bring about. That is why Keynes focuses his criticism on money rather than on private property or wage labor (much to the irritation of the left). It is not “good for us to know the consequences of all of our actions in terms of money,” he writes. “We ought more often to be in the state of mind, as it were, of not counting the money cost at all.” It is money and not these other elements of the economy that threatens to remove connections between self and world. If those connections are to be restored, the problem of money must be confronted.

These are not theoretical or speculative statements for Keynes. They are an empirical description of how we make decisions under capitalism, not only in the marketplace but also in the public square, not only as individuals or families but also as societies and states. Keynes argued that an “imbecile idiom” of costs and benefits, understood in the strictest financial terms, had colonized political language and public deliberation. If politicians did not put off much-needed projects deemed too expensive, they did them on the cheap. In the case of mass housing, they opted for slums over “a wonder-city,” because the balance sheet told them that slums “paid” while the wonder-city was a “foolish extravagance.” Other values—the beauty of the countryside, a view of the sun and the stars—were ruled out of consideration because no monetary value was attached to them. No one examined what they wanted from life and how the resources and technologies on hand might contribute to those ends. Instead, everyone looked for meaning in money, thinking it and it alone could determine “the advisability of any course of action sponsored by private or by collective action.”

As the political culture of the capitalist West descended into a “parody of an accountant’s nightmare,” Keynes found an unexpected inspiration in the Soviet Union, which he visited for two weeks in 1925. He was mostly appalled by Bolshevism and had little time for Marxism, yet he could not stifle his admiration, even awe, for what he took to be a genuine revolution in the moral and material status of money. The Soviets had attacked the notion that moneymaking, thrift, savings, and accumulation were socially honorable activities. They ranked the pursuit of money as something on the order of “the career of a gentleman burglar or acquiring skills in forgery and embezzlement.” Organizing the material world to match the moral world they wished to create, the Soviets hoped to make saving and accumulation “so difficult and impracticable as to be not worth while” at all. Their goal was a political economy in which individuals would labor cooperatively, build collectively, without relying upon the “pecuniary motive.” Individuals would undertake socially worthy projects for reasons other than personal profit and would be recognized and rewarded by society for having done so.

It’s tempting to dismiss this as a fortnight’s enthusiasm, and indeed Keynes’s second visit to the Soviet Union three years later dispelled it. Its significance, however, lies not in any revelations about communism but in what it tells us about his political economy and what he hoped it might do. The Soviet experiment, which Keynes called “a tremendous innovation,” spoke to some of his deepest stirrings as an economist. The Soviets hadn’t abolished money but had perhaps found a way to limit its import, making it serve only as “an instrument of distribution and calculation.” Operating on the credo that “if heaven is not elsewhere and not hereafter, it must be here and now or not at all,” they had broken the link between money and time. They had addressed “the moral problem of our age,” which is “the habitual appeal to the money motive in nine-tenths of the activities of life” and “the social approbation of money as the measure of constructive success.”

In the United States, Keynesianism is widely associated with a small toolkit of liberal measures such as deficit spending and pump priming, a mix of monetary and fiscal stabilizers to keep the business cycle smooth and steady. The aspirations that we see in Keynes’s statements on the Soviet Union and his essays on capitalist political culture suggest other views of his work. One is explored in penetrating detail by the economist James Crotty in Keynes Against Capitalism. Crotty argues that the central purpose of Keynesianism is neither demand management nor countercyclical tinkering but “liberal socialism,” the term Keynes himself used to describe his economic philosophy.

The main tenet of liberal socialism is that the state should cut the cord between money and time by taking over as much as three quarters of a country’s capital, bringing the frantic activities of saving and investment that plague capitalist societies under public ownership and control. In tandem with low interest rates and prohibitions on individuals’ and firms’ taking their money out of the country, the state’s management of savings and investment would achieve four goals. First, it would create full employment, which Keynes believed a capitalist economy could not bring about. Second, by funding investments in housing, transportation, and energy, the state would meet social needs that had long been neglected because greater profits were to be had elsewhere. Third, the state would end the scarcity of capital. Keynes thought that the possessor of capital was a social parasite, a “functionless investor” who was able to make money simply because only he had it to lend, much like a feudal landlord in possession of land. The capitalist also had “cumulative oppressive power,” issuing verdicts of life and death to workers and dictating policy to states. Because scarcity was the source of the capitalist’s parasitic power, ending that scarcity would lead to the “euthanasia of the rentier.”

Last, the worthiness of the state’s investments would not be measured by their rate of return but by their contribution to social well-being. Though Keynes imagined a variety of public goods that the state would bring about through its investments, the most important of those goods, for him, was the Smithian virtue of social intercourse:

Why should we not set aside, let us say, £50 millions a year for the next twenty years to add in every substantial city of the realm the dignity of an ancient university or a European capital to our local schools and their surroundings, to our local government and its offices, and above all perhaps, to provide a local centre of refreshment and entertainment with an ample theatre, a concert hall, a dance hall, a gallery, a British restaurant, canteens, cafés and so forth.

Keynes has long been accused of waging a war of economism against politics, elevating the economist above the statesman and thinking that the moral and political disagreements of a democratic society could be sidestepped or overcome by economic technicians and technocratic solutions. Robert Skidelsky compares Keynes’s early version of the economist to Machiavelli’s prince, declaring all other forms of leadership and rule “bankrupt” while staking a claim for “the economist’s vision of welfare, conjoined to a new standing of technical excellence” as the highest form of knowledge and art. Keynes, for his part, saw the economist’s work as more like that of a dentist—“a matter for specialists,” yes, but really the technique of “humble, competent people.”

Neither view captures the combination of ruthlessness and innocence, realism and naiveté, that runs throughout his liberal socialism. In his most programmatic statement, Keynes called for a high-level “thinking department,” modeled on Britain’s Imperial General Staff, with a leadership “of such power and importance” that it would rival that of the chief of the Imperial General Staff during wartime. That was the realpolitik. As Carter shows, Keynes thought that the ultimate measure of an economy’s worth was not the plenty it created but the cultural “greatness” that plenty made possible, the aesthetic excellence that a fully developed economy enabled everyone to pursue and enjoy. That was the naiveté. It presumed a far broader agreement about ultimate ends, about what made a person’s life worthwhile and meaningful, than any democracy could sustain. Crotty claims that Keynes believed that final power over decisions about investment and the ends it should be put to should reside with the public, and he uses the phrases “liberal socialism” and “democratic socialism” interchangeably. Yet Crotty offers little evidence that Keynes gave considerations of democratic disagreement and democratic decision-making much thought.

In a 1944 letter to Friedrich Hayek, his great antagonist on the question of economic planning and other issues, Keynes conceded that planning of the sort he was proposing “should take place in a community in which as many people as possible, both leaders and followers, wholly share [the planner’s] own moral position.” Yet he knew that his moral vision of an economy of cultural greatness and aesthetic excellence was not widely shared. After World War II, with parts of Britain in ruins and the task of reconstruction paramount, Keynes could be heard on the BBC pleading for “a few crumbs of mortar” to be diverted from building houses to building theaters and concert halls: “We must not limit our provision too exclusively to shelter and comfort to cover us when we are asleep and allow us no convenient place of congregation and enjoyment when we are awake.” In Russia, he added, “I hear that…theatres and concert-halls are given a very high priority for building.”

The teasing reference to the site of his previous enthusiasms suggests how isolated he sensed his position had become. Perhaps that’s why he found himself, in his letter to Hayek, retreating to a position long familiar to philosopher-kings, calling for planners whose power could be safely exercised because they were “rightly orientated in their own minds and hearts to the moral issue” and because citizens had been reeducated according to the principles of “right moral thinking.”

Never comfortable in the role of Bloomsbury Bolshevik, Keynes set out a second path for the future, one that he hoped would diminish the importance not just of money but of economic concerns altogether, without making any assumptions about what people believed or wanted from life. It was a vision of abundance and plenty, a world beyond scarcity, which made the hard power and hard choices of liberal socialism, as well as the requirement of democratic agreement about ultimate ends, unnecessary.

In 1930 he wrote, “The day is not far off when the Economic Problem will take the back seat where it belongs.” By “the economic problem,” Keynes meant more than the elimination of poverty and want. He imagined “economic necessity”—and the cult of work, of ceaseless striving for material improvement, that grew around necessity—disappearing. In this future, less than a hundred years off, our material needs would be so completely satisfied that we would “prefer to devote our further energies to non-economic purposes”—leisure, art, and virtue—to enjoy life and live it well rather than to struggle and save.4 Whatever minimal economic activity we engaged in at that point would be done, as Keynes had once imagined it was done in the Soviet Union, for the sake of others rather than ourselves.

Keynes could never decide whether his was a vision of enchantment or terror. Humanity had evolved over thousands of years for one goal, he thought, which was to solve the economic problem. With that problem solved, humanity “will be deprived of its traditional purpose.” But what if people not only wanted to work but saw it as their purpose in life, or at least one of their purposes? What would they do with their time once work disappeared? Keynes had so many things he loved to do that he wished there were thirty-six hours in a day and fourteen days in a week. Not everyone was Keynes: “To those who sweat for their daily bread leisure is a longed-for sweet—until they get it.” The antics of the leisure class hardly suggested that they knew how to live a life after labor either. “We have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy,” Keynes glumly concluded. In a post-work utopia, “must we not expect a general ‘nervous breakdown’?”

It was an ironic coda to the overtures of an earlier era. From Hugo Grotius to Smith, the materiality of our economic circumstance had been viewed as the mustard seed of our morality. In Keynes’s view, that materiality and those circumstances had to be transcended if people were to be moral. From Smith to Marx, otherness and empathy were thought to be born of our collective effort to meet our ever expanding and developing needs. Keynes thought we had to stop that process of need expansion and development and declare it complete; only when we were able to meet our material needs could we get on to the business of otherness and empathy. From Smith to Marx, the possibility of human cooperation and mutuality had been linked to the world of labor. Now cooperation and mutuality could be achieved only when we got beyond labor. From Smith to Marx, a cooperative economy of self-conscious and purposive workers had been imagined as the source and meaning of human life. Now that economy had to die so that men and women could live.

For better or worse, it was a vision for which Keynes never found a technique.

—This is the second of two articles.

This Issue

December 22, 2022

Naipaul’s Unreal Africa

A Theology of the Present Moment

Making It Big

-

1

“Empathy & the Economy,” The New York Review, December 8, 2022. ↩

-

2

While Smith had no theory of equilibrium as economists came to understand the term, he did have an account of economic forces balancing one another around a set of “natural” prices, which helped set the stage for later equilibrium theory. ↩

-

3

Though Keynes acknowledges that Alfred Marshall introduced the element of time to economic analysis, he also claims that this part of Marshall’s work is the “least complete and satisfactory, and where there remains most to do.” He makes similar claims about the analysis of money by previous economic theorists. In both claims—about the function of money and time in earlier economics—Keynes ignores the pioneering work of Austrian theorists like Carl Menger, Eugen Böhm-Bawerk, and Friedrich Wieser. See Keynes, Essays in Biography (Norton, 1951), p. 185; and Keynes, “A Monetary Theory of Production,” in The Essential Keynes, edited by Robert Skidelsky (Penguin, 2015), p. 175. ↩

-

4

In this 1930 statement, Keynes was careful to qualify his prediction, confessing that he was assuming “no important wars” in the future. Yet in his 1944 letter to Hayek, at the height of World War II, he was even more bullish about the prospect of ending the economic problem. See Keynes, “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” in Essays in Persuasion (Norton, 1963), pp. 365–366; and Keynes, letter to Friedrich Hayek (June 28, 1944), in The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, Volume XXVII: Activities 1940–1946, edited by Donald Moggridge (Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 385–386. ↩