In March 2021, as the New York winter refused to quit and tiny husks spread across my skin, plastering first my elbows, then my upper arms, underarms, eyebrows, eyelids, nostrils, and shins, I booked a room at a cheap hotel in Nassau for a week. I was in the Bahamas nominally to renew my US work visa, but the trip’s secondary objective was, in a way, more urgent: to expose, within the limits of local regulations on public nudity, as much of my body as possible to the sun.

By the time I landed on the island the rash had swarmed across my face, forearms, and waist, scabs succeeding each other to form archipelagoes that sometimes coalesced into small screaming continents of belligerent skin. There were even signs of a troubling advance into more delicate parts of the anatomy, which seemed to breach some unvoiced code between sickness and host: surely to go there was a step too far. At the airport, the customs officer quizzed me on the purpose of my visit. “Work?” she repeated incredulously; in my wretched state, I took her to mean that no one so physically hideous could be capable of employment. I powered out of the arrivals hall into a dense cotton of humid tropical air. After months of itching, I felt instant relief.

Psoriasis is a chronic, noncontagious disease, often inherited, in which a hyperactive immune system causes an overproduction of skin cells. It can take various forms, but by far its most common is plaque psoriasis. The plaques range from small flakes and rosy coins to tough bubbles and fist-size red welts. Because the sun’s ultraviolet rays slow skin growth, the disease usually goes into recess over the summer. There is no cure, but in recent decades treatments, ranging from topical ointments to clinical light therapy and prescription drugs, have become more sophisticated and more efficient at keeping the scabs at bay. For those in upper latitudes without health insurance, or for whom the ointments simply haven’t been effective, a simpler solution is to absorb as much sunlight as possible through summer, then shock the inflamed epidermis with a week of equatorial heliotherapy during the worst of the winter.

I’m not the first psoriatic writer to escape dermal distress by the sea. In the winter of 1960 John Updike, attempting to clear his skin, spent a few weeks with his wife and three young children on Anguilla. The Caribbean island was “undeveloped” and “almost entirely black,” Updike wrote in Self-Consciousness, his 1989 autobiography: “an extreme backwater in the fast-fading British Empire.” The Updikes rented a house in the village of Sandy Ground that “came with” two servants, who dutifully prepared the canned vegetables, chicken, fresh fish, and balls of fried dough on which the family subsisted for the duration of their stay. Raised in southeastern Pennsylvania, Updike had “never been among black people before” and found himself “shy and nervous” in their company. From there, his account follows a universal arc: psoriatic suffers; psoriatic finds sun; psoriatic feels better. The pleasures of Updike’s tropical convalescence were familiar to me: “the yielding abrasion of the sand, the slap and hiss of the water,” the “sun-softened humid air” that “would hit your face like an angel’s kiss at the airplane’s exit door.”

Updike returned to the Caribbean every winter for the next fifteen years, most often alone, visiting the US Virgin Islands, Antigua, Aruba, St. Martin, and Puerto Rico. Eventually the healing rays lost their power and his scabs “balked at fading away.” By the age of forty-two, he wrote in Self-Consciousness, “I had worn out the sun.” The confessional ends with Updike, by then in his mid-fifties, enrolled in Massachusetts General Hospital’s program of ultraviolet light therapy, contemplating the effects of this potentially cancerous new “phototoxicity” on his body and looking forward to old age, when the psoriatic body would be too frail for its medicine: “In my dying I will become hideous, I will become what I am.” In the end, it was cancer of the lungs, not the skin, that killed him.

Sex and the skin go together, though Updike swore that his solitary trips to the Caribbean remained chaste, whatever desire he felt for all those “stately rapt black girls…doing the mambo with their understated, utterly certain little motions.” One brief passage in Self-Consciousness mentions a young woman who worked as an assistant at the Anguilla library from which Updike borrowed Ian Fleming novels during his month on the island in 1960. The “handsomest black girl in Sandy Ground,” she often passed the house that Updike had rented for his family, giving him “a glance” as he sat on the veranda reading:

Married and young and further inhibited by my diseased skin, I could explore the possible meaning of that glance only in my imagination, at night, lying under the ghostly canopy of the mosquito netting.

That single paragraph, already erupting with onanistic possibility, forms the basis for an extended and quite unnecessary riff on Updike’s Caribbean sex life in Skin by Sergio del Molino. Molino is a writer of novels, criticism, and essayistic nonfiction; he’s perhaps best known in his native Spain for La España vacía (2016), a book that examines the cultural and political dimensions of the country’s rural–urban divide. Molino, who has had psoriasis since his early twenties, has assembled in Skin a “bestiary of monsters” for his young son, a cultural catalog of famous fellow sufferers to help explain and map the disease “that leaves me so broken.” A noble aim, no doubt, but in practice this map is mostly reduced to a single insight: the psoriatics are horny.

Advertisement

Updike’s Caribbean self-sequestration was so extreme, he claimed, that he almost never talked to anyone, except to ask for food: “Down here, my minor role as a leper became predominant, and I didn’t want to be touched.” Ignoring this account in Self-Consciousness, Molino has Updike prowling across Anguilla in a close-fitting “Lacoste polo shirt with the buttons undone” and shorts so tight they look like underpants. Dialogue between the famous writer and his librarian friend is fictionalized as high camp:

Go on like this, she said, and you’ll soon have read everything in the library. How can you have the light on so late? Don’t the mosquitoes eat you alive?…

I’ve got a good mosquito net, and I don’t skimp on repellent.

At this she got up, leaned over the counter and, from the way she half-closed her eyes, looked like she was going to kiss him, but only took in a deep breath.

You don’t smell of repellent.

And you, what do you do to stop them?

I’m a good girl and always go to bed early, she said.

Later, Molino describes Updike in bed, imagining the librarian’s “wet, hairy vagina” and its scent of discarded orchids, “a little sweet, and a little dead”: afterward “he would come so hard it started to frighten him.”

Another fictional episode in Skin has Pablo Escobar picturing himself in the jacuzzi with the female friend of a rival he suspects is gay. Stalin, also psoriatic, is imagined in his Sochi dacha planning the Soviet purges while soaking in his private pool and refining his taste for “busty blonde farm girls, innocent, free of wiles.” Joining these monsters in the bestiary of the flesh is Molino himself, eager to advertise his own prowess as a psoriatic who can still scratch that itch. (Though the literature of psoriasis is thin, the general rule seems to be that you’re allowed one bad pun per piece.)

Europe remains a place, it seems, where it’s quite normal for a male writer in his forties to reflect unironically on his sex life in a wistful mode. We see Molino at twenty-one, during his first outbreak, coming on to his roommate; later, psoriatic and married, making love to his wife following a plunge in the restorative waters of a Spanish spa town; and in a flashback to pre-psoriatic adolescence, climaxing in his pants on first contact with a breast. Not all of this has to do with psoriasis, but then not everything does. Molino’s frequent digressions into adult fan fiction reflect the challenges that psoriasis presents as a subject of literary exploration.

“At War with My Skin,” the chapter in Self-Consciousness that recounts Updike’s psoriasis years, runs to thirty-six pages. Much of it is padded with mystico-philosophical ruminations on the meaning of the disease, which offer Updike a useful opportunity to reemphasize the singularity of his literary gift:

Was not my sly strength, my insistent specialness, somehow linked to my psoriasis?… Only psoriasis could have taken a very average little boy, and furthermore a boy who loved the average, the daily, the safely hidden, and made him into a prolific, adaptable, ruthless-enough writer. What was my creativity, my relentless need to produce, but a parody of my skin’s embarrassing overproduction?

Search for other psoriatic writers who have exposed the arousals of the skin and the ego to this level of detail and you’ll come up blank. Vladimir Nabokov had the scabs, but a page-long excursus in Ada represents the sole treatment of the disease in his fiction. For centuries psoriasis was confused with leprosy, and “thousands if not millions” of sufferers, writes that novel’s Dr. Krolik, “crackled and howled bound by enthusiasts to stakes erected in the public squares of Spain and other fire-loving countries.” Only since the nineteenth century has the disease been understood as a discrete condition. Today it affects more than 3 percent of the adult US population, or almost eight million people; worldwide, psoriatics are estimated to number at least 100 million. Often when I’ve told someone I have psoriasis the response comes, “Oh yeah, so do I.” This usually occasions a solid two-minute exchange about spots, patches, scratches, and sores before the conversation moves on to other subjects. Psoriasis is a disorder that walks among us.

Advertisement

The World Health Organization describes psoriasis as a “serious global problem,” but it’s not quite serious enough for literature, which remains the preserve of real killers like cancer and AIDS. And yet it’s more than a mere embarrassment; the complications that can arise from psoriasis include arthritis, diabetes, and depression. Psoriasis seems bound to occupy a dramaturgical middle ground, not quite heavy enough for medical tragedy, not quite light enough to be played strictly for laughs. Though relentless, it is not lethal.

This ambiguity might have made psoriasis an attractive object of literary attention in an earlier era—in the nineteenth century, say, as a complement to the blooming literature of asthma, dyspepsia, and fatigue—but it was recognized too late for canonization by the Romantics. In today’s literary marketplace, readers have gravitated toward writing about more deadly or unusual conditions like Lyme disease (Porochista Khakpour’s Sick), unexplained shaking (Siri Hustvedt’s The Shaking Woman, or A History of My Nerves), and chronic idiopathic demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (Sarah Manguso’s The Two Kinds of Decay). There’s also the problem of plot. Not much happens when you have psoriasis. The plaques appear, they multiply, and you complain a lot, or toss the discomfort into the sinkhole of the psyche. Whether or not you seek treatment, eventually the weather turns, the skin clears, and the story pauses.

Updike’s one earnest attempt to reckon with this “intimate rankness” in fiction—The Centaur, published in 1962, toward the start of his course of Caribbean desquamation—is a testament to the difficulties of freighting a condition whose most dependable constant is ephemeral irritability with the weight of novelistic circumstance. Over the course of three rural Pennsylvania days in 1947, science teacher George Caldwell and his psoriatic fifteen-year-old son, Peter, battle to survive the triple headwinds of small-town sadness, a winter snowstorm, and automotive failure. As one of the novel’s narrators, Peter squeezes his scabs for all they’re worth. Nearly every conceivable aspect of the disease scores a mention: its funny Greek name (“so foreign, so twisty in the mouth”), its seasonality (“January was a hopeless time”), the analogies of its epidermal distribution (islands, constellations), the mortification of its sufferers, their lust for those with smooth skin. There are several passages describing Peter’s itches, which even a writer of Updike’s “insistent specialness” can’t do much with: “‘I think so,’ I said, furious to scratch my itching arms”; “My skin itched furiously.” Dandruff is also given particular attention. (Having dandruff is not the same as having psoriasis, but neither plays well with a red shirt.)

But is snowfall on shirtsleeves enough to make art? Updike presented The Centaur as a refashioning of the Greek myth of Chiron and Prometheus, translating the tragedy of original sin (Prometheus’s gift of fire to humanity) into a melodrama of the original skin. In the rare passages where Peter is not simply in misery or describing an urge to scratch himself, the central question is whether he will reveal his hideous secret to his girlfriend. Eventually, he does; she tells him she doesn’t care, that the psoriasis is part of him. This being an Updike novel, Peter rewards her forgiveness, but mostly himself, with sex. Reviewing The Centaur in these pages in 1963, Jonathan Miller began: “This is a poor novel irritatingly marred by good features.”* Nabokov, for all his reticence to grapple with their shared affliction in his own work, called it “Updike’s best novel.” Flake recognized flake.

Nabokov did, in fact, address his own psoriasis—or “my Greek,” as he preferred to call it—in writing. But he reserved his observations for private correspondence. One outbreak in 1937, around his thirty-eighth birthday, was particularly violent, and because Nabokov was living apart from his family at the time, an account is preserved in the letters he sent to his wife, Véra, still stuck in Berlin with their three-year-old son, Dmitri. “My Greek tortures me so much,” he wrote on January 27, adding a few days later:

I won’t tell you about the unbearable sufferings imposed on me by the Greek; the itchiness doesn’t let me sleep, and all the linen is covered in blood—terrible…. Everything would be fine, if it weren’t for the damned skin.

On February 4 came news of more flagellation at the hands of the Greek: “The psoriasis is only getting worse.” Then, on February 15: “The most awful thing is the itch. I dream madly of peace, ointment, sun.” Relief arrived when Nabokov was offered a free course of ultraviolet light therapy, then in its early development. Within days his mood brightened. “My Greek is getting wonderfully better from the sun.” By mid-April the recovery was complete: “I’ve grown fatter, more tanned, changed my skin,” he wrote. This is the reaction of any convalescent: health is never felt more fully than at the moment of exit from illness.

Amid this bout of Greco-Russian wrestling, Nabokov was not so secretly conducting an affair with a fellow émigré, Irina Guadanini. Nothing about the suffering visited on him by his skin condition prevented Nabokov from pursuing this “vivacious and highly emotional blonde,” as Stacy Schiff describes Guadanini in Véra (Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov). Before long Véra caught wind of the relationship. Faced with a choice between his family and, as he put it, the “indescribable, unprecedented” feelings he had for his new love, Nabokov eventually broke off the affair and returned to the stability of a marriage he had once called “cloudless.”

Molino has read his Sontag, so he understands that in discussions of illness, metaphor all too often has the effect of making the patient culpable, turning disease into the external manifestation of some temperamental defect. Rather than argue that character causes disease, then, he proposes that disease informs one’s conduct. Without his Greek, Nabokov would have “thrown it all away for love,” Molino speculates. “The psoriasis acted like a bodily reminder of his obligations” to Véra and Dmitri. As Molino sees it, Nabokov’s novels are monuments to the skin as something “at once shameful and sublime” and only fully make sense with the knowledge of their creator’s disease, a ravishment of the untouchable that works such as Lolita explored along other lines.

Applying the same logic—a kind of reverse somatization—a different chapter of Skin has Stalin cooking up the Great Purge as a way to punish the world for his psoriasis. “Those who are made into freaks by skin conditions have a desire to pass on their blemishes, eruptions and wounds to everyone else,” writes Molino. Psoriatics, in other words, can either wear their spoiled skin as a straitjacket (Nabokov) or carry it like a permission slip (Stalin). But which one is it? If psoriasis explains everything, it explains nothing.

Molino’s exercise in pop dermatology reveals something deeper about the social energies awakened by this particular abomination of the skin. The most famous psoriatic in the world today is Kim Kardashian. For the past decade Kardashian, who had her first flare-up at twenty-five, has spoken about her experience with candor. “I am the only child my mom passed down her autoimmune issue to,” she wrote in 2019. “Lucky me, lol.” She documents her lesions for millions of social media followers, offering tips on lifestyle changes to keep them in control. (What works for her: a plant-based diet, sea moss smoothies; what doesn’t: coconut oil.) Cyndi Lauper, a fellow sufferer, released a single in 2018 called “Hope,” intended as an anthem to inspire the world’s psoriatics. (Like Molino I was not inspired, but I appreciated the gesture.)

Though both Lauper’s and Kardashian’s contributions are delivered in the obligatory language of corporate brand-building—Kardashian speaks Goopily of her “psoriasis journey,” and “Hope” was sponsored by a pharmaceutical company—it seems fair to observe, as Molino does, that famous women with psoriasis have in general used their celebrity to draw more attention to the disease and share information on how best to confront it. Famous men with psoriasis, on the other hand, have taken it as an invitation to think more about themselves.

What does it all mean? In their respective ways both Molino and Updike have attempted to answer this question, but their writing on psoriasis is either superficial or self-consciously overwrought. Skin is not much more than a travelogue of the body, a jaunty recap of the summer vacations and health-affirming sexual escapades undertaken in Molino’s quest for dermal relief. The Centaur attempts something more ambitious but buckles under the weight of its own monumentality: however hard Updike tries, a story of teenage itching in small-town America can’t quite bear comparison to the Greek myth of the origins of human mortality and civilization, and using the latter to tell the former reduces psoriasis to a mere proxy rather than capturing what’s unique or unusual about the disease.

My psoriasis is hereditary; my maternal grandfather and aunt both have the condition. When I was a kid, my Greek-Cypriot mother often warned of the dangers of failing to moisturize dry skin. “You don’t want to get psoriiiasis like your pappou and theia,” she used to say, pronouncing the dreaded malady’s name in its original Greek and drawing the second syllable out for malevolent emphasis. I received my diagnosis at the age of fifteen. For weeks afterward I convinced myself that psoriasis could serve as a cultural bridge to Greece, since the only sufferers of this widespread but somehow socially invisible condition I knew were members of my own family, and the illness itself bore a twisting, sibilant, unmistakably Greek name. I began to believe that psoriasis was both “my Greek” (in the Nabokovian sense) and a spur to improve my Greek (in the linguistic sense). After a while I realized that psoriasis has no national favorites, and redevoted myself to the important work of moisturizing. My Greek skills remain a work in progress.

This youthful misinterpretation may reflect a collective ignorance. Psoriasis is widely seen as something that happens to rich white people, an assumption that literature reinforces. In Self-Consciousness, Updike contrasted his own blighted paleness with the skin of Caribbean locals, reproducing a host of limp tropes about white anxiety and black freedom. Molino, meanwhile, addresses race through a winding anecdote about a dark-skinned childhood friend, but the conclusion he reaches—“Skin doesn’t need to be unhealthy to become a stigma”—feels trite and parenthetical to Skin’s larger concerns. In truth, our understanding of the disease’s worldwide prevalence is limited. According to the Global Psoriasis Atlas, 81 percent of the world’s countries lack data on the epidemiology of psoriasis. The disease’s known distribution reflects nothing more than the poverty of the information available to us.

There’s something Beckettian about persistent itching, a reminder of our irritating physicality, of how being alive can feel monotonous and endless. But if psoriasis is mundane, it also remains mysterious; it’s at once tedious and elusive, known and misunderstood. This tension is what gives psoriasis its special character, but it’s absent from Skin. Chronic and incurable, psoriasis is the archetype of the disease you can live with. It’s an accidentally modern affliction, fit for a world in which the biggest problems are managed rather than solved. The psoriatic seeks comfort in resilience and adaptation, but the most enduring feature of the disease is uncertainty.

“My skin was my enemy,” Updike wrote in Self-Consciousness, before concluding a few pages later, “Psoriasis is my health.” The disease “was not really me,” he maintained, while insisting it “told me who I was.” Psoriasis propelled Updike into the sun, but writing, “a thoroughly shady affair,” called him back to the shadows. Psoriasis is both a surplus of skin and an aesthetic deficit, an immune disorder that’s highly orderly in its behavior, a natural error whose best correction is found in nature. Just as it’s pulling us into sickness, it sends us back to health. Although psoriasis is a common condition, its true prevalence remains unknown, its cultural presence slight. “Nobody,” Molino writes, “knows what being an ill person is supposed to entail.”

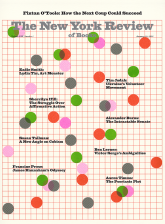

This Issue

January 19, 2023

Dress Rehearsal

When Diversity Matters

The Instrumentalist

-

*

“Off-Centaur,” The New York Review, February 1, 1963. ↩