“Yesterday, the gigantic rocks of Montserrat glowing red in the distance…”; “four days ago, I was looking at the great glow outspread in the night sky over Berlin…”; “the vast deserted square, bathed in a strange, extremely pale blue dawn glow…”; “a great red glow from the tumultuous squares…”; “the Popo puts me in mind of the Kazbek; the reddish glow over on the plains at the foot of the mountains of the valleys of Georgia…”; “on the evening of the verdict, the sky above the city glowed purple. I walked towards the glow: the whole of the San-Galli works was in flames…”; “the sky glowed white until sunrise, captivating every glance…”; “a glow of pink watercolor shimmers between the heavy clouds and spreads over the small city…”; “a dull glow reached them from the misty sky…”; “he thrust his hands into his pockets and went out alone, beneath the night sky, black with a vague purple glow.”

Even when the light is inseparable from violence—bombs, tumult, verdicts—everything that glows is precious to Victor Serge, is a source of wonder, a glimmer of possibility beyond the catastrophe of the present. Fleeing across the rooftops of Petrograd in 1919, exchanging gunfire with the anti-Communist Whites, Serge “treasured an unforgettable vision of the city, seen at 3 am in all its magical paleness.” So much glows in Serge, so much vibrates. “Not a speck of matter,” he writes in his Notebooks, “not a fragment of space that doesn’t vibrate and live.”

The morning light is milky yet transparent. An enchantment you breathe in, that penetrates you through the eyes and every pore of your skin—and touches your soul. The brain vibrates with a joy of being for which there are no words.

Serge’s materialism has a spiritual element; physics and metaphysics, frequencies and faith, interpenetrate: “The stars vibrate, eternity’s chant.” Or “the room, made from the velvet blue-gold of the imperial theatre vibrates suddenly with this clear human joy, because a sovereign artist sang.” Or in the poem he wrote the day before he died, penniless in Mexico, addressing the anonymous model for an anonymous artist who crafted a pair of terracotta hands:

How vain the centuries of death before your hands…

The artist, nameless like you, surprised them in the act of grasping—who knows if the gesture still vibrates or has just ended?

Serge’s late novel Last Times (1946), recently republished, ends with this parenthetical: “(…but nothing has ended.)”

I start with the Serge of endlessness and light and vibration and souls and stars (“The stars shine with a supernatural brilliance which heightens your taste for living”) because he is so often described (accurately) as the persecuted chronicler of the darkest times, or assumed (inaccurately) to be a mere ideologue, that many people of my generation groan when you bring up his novels—assuming they’ve heard of him—as if you’re suggesting they do penance for having ever read for pleasure. But Serge is also the laureate of the light in the dark, a writer sensitive to flashes of beauty (even when he’s fleeing across rooftops)—not because such fugitive moments are beyond politics (although they are beyond any party), but because they are its ground, the basis of his indefatigable sense of collective possibility: everything lives, everything vibrates. How vain the centuries of death.

Yet he is also a writer of possibility betrayed. One of his great themes is how revolution becomes totalitarian—and how one might break with the totalitarian without becoming merely reactionary, without abandoning the emancipatory energies that gave rise to the effort to remake the world in the first place. Needless to say, Serge’s experience of this struggle is extreme and historically specific, but what if some version of this problem recurs at intervals: How and when must one refuse a drift into groupthink or dishonesty, into whatever party line? How does one name the authoritarian moment in a liberatory movement, while also refusing to disavow the necessity of the initial cause? I don’t pretend to have an answer to these questions, but it’s a sign of Serge’s relevance if you feel their force.

Serge’s biography is so remarkable—“I have undergone a little over ten years of various forms of captivity, agitated in seven countries, and written twenty books”—that one has to begin with a sketch of his life, even if I’m ultimately suggesting we should put a little distance between the author and his fiction.

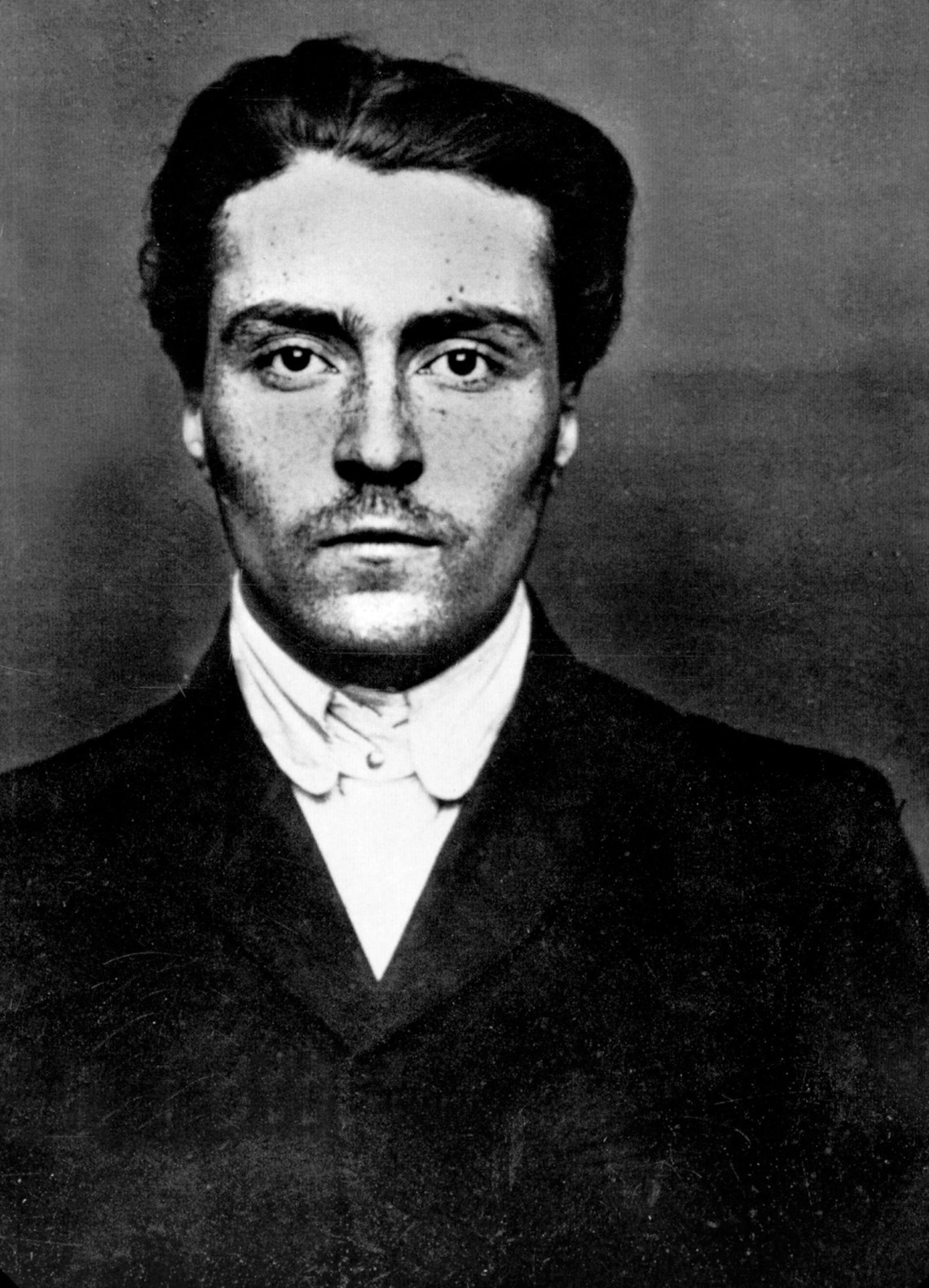

He was born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich to anti-tsarist exiles in Brussels in 1890. (He was related to the chemist Kibalchich who constructed the bomb that killed Alexander II.) His family was poor enough that Serge’s younger brother died of malnutrition at the age of nine. (“I put ice on his forehead, I told him stories…his eyes glittered and grew dim at the same time.”) Surviving in part on bread soaked in coffee, Serge was reading Kropotkin in his early teens; by 1909 the young anarchist had left Belgium and moved to Paris, where he was marginally involved with the Bonnot Gang (anarchist, vegetarian, teetotaling bank robbers credited with inventing the motorized getaway). Serge was arrested, told if he ratted out the gang he’d be let go, but he refused; he was sentenced to five years, the first of his many harrowing experiences of incarceration, and eventually the basis of his first novel, Men in Prison (1930).

Advertisement

Expelled to Spain upon his release, he was active in the anarcho-syndicalist uprisings of 1917 in Barcelona (and began to write under the name Victor Serge; Serge’s major writing was in French). And “then, awaited so keenly that we eventually wondered whether we should still believe in it, the Revolution appeared.” Serge tried to reach Russia via France but was detained for violating his expulsion order and spent more than a year in a French concentration camp; while he studied Marx, a quarter of the inmates around him died from the Spanish flu. He was finally sent, as part of a prisoner swap, to Petrograd in 1919, a site of revolutionary hope and also “the metropolis of Cold, of Hunger, of Hatred, and of Endurance.” (See, in addition to his 1951 Memoirs of a Revolutionary—which I will try to stop quoting—Serge’s chronicle Year One of the Russian Revolution, published in 1930.)1 He married Liuba Russakova, Lenin’s former stenographer, who gave birth to their son, Vlady, in 1920 and to their daughter, Jeannine, in 1935.

He joined the Bolsheviks, worked for the Comintern, fought during the siege of Petrograd, and was sent to Berlin to support the German revolution of 1923 (a sojourn that yielded Witness to the German Revolution, first published in French in 1990). After a spell in Vienna, and after the death of Lenin, Serge returned to the Soviet Union to support Trotsky’s Left Opposition. As a result of his open criticism of Stalin, he was arrested and expelled from the party in 1928. He was released, but lived in “semicaptivity” in Leningrad, where he completed three novels—Men in Prison, Birth of Our Power (1931), and Conquered City (1932)—“an informal trilogy,” as Richard Greeman (a tireless Serge scholar, translator, and advocate) puts it, “chronicling the birth pangs of the revolution.”

Soon after the appearance in France of Conquered City, Serge was again arrested and this time subjected to months of brutal interrogation. He refused to confess to anything and, in 1933, was internally deported with Vlady to Orenburg, in the Urals, where they nearly starved; Liuba, whose mental health was crumbling, remained largely in Leningrad. (But—this is the Memoirs again—“we thought that the light from the sky was rich and pellucid as nowhere else, and so it was.”)

As a result of international protest—his writings were known in France; notable supporters included Romain Rolland and André Gide—Serge was allowed to leave the Soviet Union in 1936, just four months before the first Moscow trials. He spent the next four years primarily in Paris, documenting—despite great poverty, despite what Greeman calls the “Communist campaign of slander that effectively closed the major media to him”—the growing Soviet terror (and double-dealing of Stalinists in Spain and elsewhere). He wrote tirelessly: From Lenin to Stalin (1937); Destiny of a Revolution (1937); Portrait de Staline (1940). Then, returning to fiction, Serge composed Midnight in the Century, a novel informed by his Orenburg experiences depicting a group of Bolsheviks reckoning with the Stalinist corruption of the revolution; published by Grasset in 1939, it was a contender for the Prix Goncourt, as close as Serge ever came to literary success.

But the Wehrmacht was approaching Paris. Serge’s books were suppressed, and he fled to Marseille in 1940, where he spent a desperate year trying to arrange passports while being threatened by both the Gestapo and the NKVD. (This year eventually informed his novel Last Times.) He finally escaped with Vlady to Mexico on a steamer whose other passengers included André Breton, Anna Seghers, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. (Liuba was at this point in a mental institution in the South of France; Serge was now married to Laurette Séjourne, who brought Jeannine to Mexico in 1942.) In Mexico Serge composed—while “taking in pre-Columbian monuments, consorting with refugee Surrealists, dodging Stalinist hit men,” as J. Hoberman recently put it in The New York Times—his unforgettable Memoirs and three novels: Unforgiving Years (1971), The Case of Comrade Tulayev (1948), and Last Times. Only the third (Serge’s attempt to write a popular novel) was published in his lifetime; the other three—to my mind his three great books—were “written for the drawer.”

Advertisement

“One day in November 1947,” writes Vlady Serge,

my father brought a poem to my house in Mexico City. Not finding me at home, he left to take a walk downtown. From the central Post office, he mailed me the poem. A short while later, he died in a taxi…. A few days later, I received his poem: “Hands.”

L’artiste sans nom comme toi les a surprises dans un mouvement de prise

dont on ne sait s’il vibre encore…

Serge is one of those writers famous for being unread, widely known for being neglected. Susan Sontag’s 2004 essay “Unextinguished (The Case for Victor Serge)” is a particularly thorough attempt to account for “the obscurity of one of the most compelling of twentieth-century ethical and literary heroes,” but part of the answer is right there (as Sontag knows), in the close proximity of the ethical and the literary, in all the talk of heroism: if you are presented with the image of Saint Serge and expect that the books are primarily long records of revolutionary mortification, relentless catalogs of terror, reading him might remain something you only always meant to do. And Serge’s reputation as a selfless, wronged, incorruptible truth teller can make people think the art is beside the point: Why read the fiction of a truth teller, especially one who wrote so many nonfiction books? (And the sheer number of books is intimidating, potentially off-putting; do you have to read all twenty?) I know of at least one professional historian of the international left who says she has “skipped” the fiction.

Serge’s literary reception has also suffered from his own cosmopolitanism: fluent in five languages, he is, as Sontag puts it, “a Russian writer who writes in French,” which “means that Serge remains absent, even as a footnote, from the histories of both modern French and Russian literature.” He was a Dostoevsky of revolution and reaction writing in the wrong language. Serge’s internationalism has, according to Greeman, prevented him from “being domesticated into the university, where departments are divided into national literatures like Russian and French, both of which apparently ignore his work”; like Serge himself, the books are stateless.

Then there is the fact that Serge’s writing was ignored or suppressed during his lifetime, and in the decades following his death, because nobody in the international left wanted to hear criticisms of the USSR or Stalin; Serge was treated with indifference or contempt by those operating under “the conviction that to criticize the Soviet Union was to give aid and comfort to Fascists and warmongers,” to quote Sontag. At the same time, as an unrepentant professional revolutionary who had “agitated in seven countries,” he was far too much of a radical to be embraced by anybody who wasn’t on the left. (What I don’t understand in Sontag’s characteristically brilliant essay is her confidence in referring to Serge as an “anti-Communist,” which seems to conflate communism and Stalinism, which is of course exactly what Serge—at risk to his life—refused to do. While Bolshevism contained the seeds of Stalinism, Serge believed it also “contained other seeds, other possibilities of evolution.”)

Indeed, the characters in Serge’s novels take very seriously the idea that to criticize the Soviet Union is to give comfort to the enemy. Part of the problem with the discourse of heroism surrounding Serge is that it can blind us to the ambivalence within his fiction, especially his two great novels, The Case of Comrade Tulayev and Unforgiving Years. The Case of Comrade Tulayev describes the ramifications of a more or less random murder: a young man who has come into possession of a pistol almost by chance impulsively shoots a high-ranking Communist official on a dark street. This sets in motion a sprawling investigation that entangles a network of suspects who of course have nothing to do with the crime in question, allowing Serge to depict the apparatuses of Soviet terror in all their murderous, repressive, inquisitorial absurdity.

But one of the most disturbing and fascinating aspects of the book is how many of the sincere old Bolshevik characters—accused of a crime they didn’t commit—nevertheless struggle with whether they should confess or otherwise accept their doom. Is it not just one more sacrifice demanded by the revolution? Isn’t it better to die for the right cause for the wrong reasons than to give ammunition to your international enemies? “They assure themselves that it is better to die dishonored, murdered by the Chief, than to denounce him to the international bourgeoisie,” laments Dora, the wife of Kiril Rublev, one of those original Bolsheviks who knows he will soon be purged. “He almost screamed, like a man crushed in an accident: ‘And in that, they are right.’”

In the first section of Unforgiving Years, a veteran revolutionary named D, disgusted with the waves of repression, resigns from the party and must run for his life through pre-war Paris. (I should say in passing, because it’s not going to come through in what I’m quoting, that Serge’s books offer plenty of noirish thrills; it sounds petty to say so, given his subject matter, but it’s part of why the writing feels alive.) Once again, it’s not just D’s courage that’s notable, but his uncertainty, his sorrow about what he will lose if he makes his break:

The conviction that we remain—however wretched—the most farsighted, the most humane beneath our armor of scientific inhumanity, and for that reason the most endangered, the most trusting in the future of the world—and unhinged by suspicion! Ah! With all of that falling away from me, what will be left for me, what will be left of me? This nearly old man, so wisely rational, being rattled along by an ailing taxi through a pointless landscape… Wouldn’t he be better off going home? “Shoot me, comrades, as you shot the rest!” At least such an end would follow the logic of History (since we have offered our lives to History…).

D does abandon the party that’s been “unhinged by suspicion.” But to be cut off from the Soviet experiment—even in its bankrupt and increasingly murderous form—is for D, is for many of Serge’s characters, to be cut off from that life force, that glow, that collective eros. (That the loss is in part erotic is indicated by the formulation that occurs to D a few lines later: “To live only for oneself is barren—like masturbation.”) Here we see how that light and vibration in Serge isn’t all warm and fuzzy, isn’t mere lyrical sentimentalism; it might sponsor selflessness or justify self-destruction or the destruction of others. Serge’s fiction doesn’t just celebrate heroic individuals who speak truth to power, but depicts people for whom the heroic individual is a contemptible, arid, bourgeois concept. This means his disillusioned revolutionaries must choose between modes of betrayal: betray the revolution through complicity with the purges, or betray the revolution by breaking with the party, thereby aligning with its enemies, and thereby losing a sense of their lives as meaningful.

I’m not saying we should celebrate these characters for being torn about whether it’s better to be shot by the party or to disavow it, but I think that conflict is central to the specific intensities of these books, and that focusing on Serge’s heroism obscures it. It’s true that Serge’s writing powerfully documents how, from the establishment of the Cheka on, suspicion and score-settling and bureaucratic terror increasingly eclipsed all other aspects of the revolution, and it’s true that Serge himself courageously (to put it mildly) refused to capitulate to this inquisitorial logic, would sign no false confession, but these truths—which are the truths that dominate the conversation around Serge—can keep us from seeing how unsettled, how unsettling the fiction is, especially around questions of individual and collective responsibility, agency, and value. His great novels are dramas of dissent, of conscience, but without liberalism. It is a genre of political fiction with few entries.

It’s unusual to see a novelist seriously entertain—even if he ultimately rejects—a worldview that would justify his own destruction (and the destruction of millions): the view that questions of individual guilt or innocence are irrelevant to the “logic of History.” (“And it was an old mistake of bourgeois individualism to seek truth for the sake of conscience, one conscience, my conscience. We say: To hell with my and me, to hell with self, to hell with truth, if the Party can be strong!”) And just as Serge’s novels struggle with the value of individual innocence, they refuse any easy distribution of individual guilt. The third section of Unforgiving Years takes place in the hellscape of Berlin in the last days of the war. Remarkably—for any novelist of the time, let alone one with his experiences—Serge depicts, according to Greeman, “Germany’s defeat from the point of view of ordinary middle-class Germans seen principally as victims.” (That Serge represented the Allied firebombing and its costs at all was certainly exceptional at the time.)

In one memorable scene, a convoy of Americans arrives in the ruined city. There is a journalist traveling with the troops. He’s looking to interview a local and selects, from among the stunned and desperate residents gathered around the jeep, Herr Schiff, whom the journalist takes to be an “average elderly German, former officer and civil servant by the looks of him.” Schiff is a semi-senile schoolmaster who tends his lilac bushes while the world burns around him; we have heard him spew garbage about the Aryan race in his classroom, where he is also known to pontificate on

subterranean fire, on earthquakes, on the submersion of entire continents beneath the seas: for example Atlantis, mentioned by the divine Plato, northern Laurentia, Gondwanaland to the southeast… The earth was replete with lost continents.

He suspects a student is a Jew being harbored by Catholics but doesn’t do anything about it. The mashup of mythologies that constitutes his supposed erudition makes him a largely pathetic figure; there is a total disconnect between his weltanschauung and the world.

The journalist begins by asking Schiff what he thinks about Americans, and gets a typical Schiff response:

A didactic question could never catch the professor off guard, for he was constantly putting them to himself, and supplying interminable answers in the form of monologues upon eugenics, the world conceived as a representation, the genius of race, or the political errors of Julius Caesar and Wilhelm II.

Then the journalist asks: “Do you people feel guilty?”

If there was one emotion which had never been experienced by Herr Schiff (at least not since his adolescent religious crises) in his half century of diligent service, that emotion was guilt. It is healthy to live one’s life in the meticulous fulfillment of duty. The schoolteacher cocked his head obligingly. “Pardon me. I didn’t quite catch…?”

“Guilty for the war?”

Schiff’s gaze swept the horizon of the broken city, strewn with the dead doves of humiliation. The grander generalizations existed for him on a different plane from everyday reality. The Second World War was already down as a great historical tragedy—a quasi-mythological one—which neither Mommsen, Hans Delbrück, Gobineau, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Oswald Spengler, or Mein Kampf could elucidate entirely… The sons immolated themselves upon the altar of blind gods. A new, unholy war, unworthy of human nobility, had begun with the destruction of Altstadt; and this war alone existed in reality.

“Guilty?” Herr Schiff said in flinty tones, with the air of a livid turkey-cock. “Guilty of that?” (And he bobbed his head at the surrounding devastation.)

“No,” the reporter said patiently, not quite grasping the response, “guilty for the war.”

“And you,” Herr Schiff retorted, “do you feel guilty for this?”…

“My dear Professor,” the journalist began, striving for an offensive politeness, “you started this war…You bombed Coventry.”

“I?” said Schiff, in frank astonishment. “I?”

I don’t see Schiff principally as a victim; he is hardly innocent in his mindless “diligent service” to the Fatherland, and I don’t share Greeman’s confidence in reading this scene as Serge having simply “satirized the cliché of German collective responsibility.” That said, the American’s desire to parse total war neatly into questions of individual guilt is indicted here; Serge makes us feel acutely how incommensurate that “I”—any “I,” but certainly this schoolteacher’s—is in relation to the historical forces at issue.

Serge’s simultaneous ambivalence about the status of the individual and sympathetic investment in individuals (and his keen eye for particulars) provides the constitutive tension of his best fiction. “He never saw anybody as an anonymous agent of historical forces,” wrote John Berger in 1968. “It was methodologically impossible for a stereotype to occur in Serge’s writing,”2 and yet, as Serge himself put it: “Individual existences were of no interest to me—particularly my own—except by virtue of the great ensemble of life whose particles, more or less endowed with consciousness, are all that we ever are.” (Those particles, those specks of matter, vibrate.) To a certain degree, of course, the tension between stereotype and specificity is built into the novel as a form: we praise a novelist for depicting contingency vividly, for her powers of individuation, but any individual character will also always be caught up in questions of exemplarity—what is being said about gender or race or class or the historical moment by this vivid depiction of a particular figure. But given Serge’s subject matter and circumstances, this push and pull between individuation and abstraction has a specific charge.

The most obvious formal signature of this tension is Serge’s experimentation with choral or collective protagonists. There is never a single “hero” in his books. In the early Birth of Our Power, for instance, Serge largely deploys a narrative “we.” The book begins in Spain, describing the doomed struggle of leftists to take power in Barcelona in 1917; it then shifts to Petrograd, where the Reds succeed in holding power against the Whites. Serge—he was writing in “semicaptivity” in Leningrad, after he’d been expelled from the party—isn’t simply describing defeat in Spain and victory in Russia. Instead, he’s depicting, as Greeman has it, “victory-in-defeat” and “defeat-in-victory”: how the collective possibilities alive in the first, failed struggle are betrayed by the drift of the Reds into terror.

The “we” in Birth of Our Power is central but unstable: there are stretches of first-person narration; there are plenty of named characters depicted in the third person. It’s the way the perspectives combine into the “we,” then separate again, that’s most interesting (and impossible to demonstrate with a short excerpt). While Birth of Our Power is subtler than I’m making it sound (and subtler than the title makes it sound), I still find the less programmatic versions of this experiment more fascinating, as when D briefly takes over an early subsection of Unforgiving Years, recounting in the first person a hallucinatory experience of being wounded in China, before the book shifts back to the third person. (Serge is particularly good at using the first person to dramatize its dissolution—D is largely delirious in this passage, near death, remembering fragments of his life and loves: “Valentine was present whenever I wished for her, we were fused impossibly into a single joyous vibration.”)

The early “we” feels like Serge declaring something, bending the artwork to an idea that precedes it, the aspiration of a proletarian collective subject; the later experiments with voice and vantage feel less assured, more searching, as if Serge discovered them in the act of composition. (Such experiments are largely missing from Last Times, the novel of Paris on the eve of its fall to the Nazis, the one book Serge wrote with the explicit hope of gaining a wide readership and alleviating his poverty, and the only novel to appear in English in his lifetime. Last Times still abjures a single hero, but the omniscient narration is stable, Balzacian; there is plenty to admire or argue with in the book, but much of my experience reading it involved registering the loss of the tension that characterizes his more formally restless work.)

The tension between the individual and the collective inevitably arises in decisions about grammatical point of view (and the refusal of a single “hero”), but in Serge it operates on multiple levels. Consider, for example, how the problem flickers across his faces, particularly in Unforgiving Years. (That this might seem a trivial feature to attend to—especially in sweeping works about epochal upheavals—is part of the point; I want to suggest how the problem is so deep in Serge that you can find it on every scale.) The novel has four parts: part one, as mentioned, is set in Paris, part two takes place in Leningrad (under siege by the Nazis), part three is in Berlin, and part four is set in Mexico, where D has fled. The only character in all four sections of the book is Daria, another Comintern agent, a woman who has known D since the early years of revolutionary agitation and who initially declines to escape with him, instead returning to Russia, where she fights for Leningrad. (She is behind the German lines in part three; in part four she seeks out D in Mexico.) “All faces are illuminated in a single one,” Daria thinks at one point about the face of a soldier who has become her lover, “yet his appeared incomparable, its radiance lighting up souls without number.” “The face stirred the totality of life, internal and external simultaneously.” Or, later:

His nose made a straight line down the middle of his face and his slash of a mouth drew a horizontal line below, as if nature were experimenting with a diagram; but nature’s plan had been foiled by large deep-socketed eyes, resembling the eyes of visionary saints drawn by the ancient icon painters… The soul trumps the diagram.

It’s as though Suprematism and ancient icon painting are competing in the face, just as Serge is often testing new combinations of modernist and realist tendencies in his fiction—mixing stream of consciousness and fragmentation with passages that sound more like Tolstoy or Balzac. The Case of Comrade Tulayev and Unforgiving Years strike me as Serge’s finest books precisely because these combinations are so unsettled, because formal problems are charged with the larger questions of consciousness and commitment with which Serge is wrestling. I less “see” Daria’s lover through such descriptions than I observe her—that is, I observe Serge—experimenting with how to make the “great ensemble” visible, make it glow, in the “individual existences” without giving way to soulless abstraction.

Serge, of course, doesn’t resolve the problem of how art can both honor and transcend the individual, how to attend to the specific face and the so-called faceless masses, how to move beyond the merely visible without embracing what he saw as the soulless fungibility of abstraction. He doesn’t resolve the problem, but he activates it powerfully in his best fiction, both in the stories he tells and in his strategies for telling them. In the strange poetic fragment that serves as an epigraph to the fourth section of Unforgiving Years, art’s capacity to preserve the human faces of the past offers something like hope among the ruins:

So many funeral masks

lie preserved in the earth

that nothing yet is lost.

When Serge’s friends buried him in Mexico in 1947 they were required to give him a nationality. They put down that he was a citizen of the “Spanish Republic,” a country that didn’t exist. It’s tempting to think of Serge as an emissary from a counterfactual country, a country that might have flowered from one of those “other seeds” of the 1917 revolution: Could there have been a Soviet literature that struggled openly and experimentally with questions of the one and the many from a humane yet radically left perspective? That question raises a million questions, but those books Serge wrote for the drawer go on posing it.

For some readers of Serge, the fiction will always be secondary—the pastime he turned to when he was sidelined from political activity. Some will treat his novels primarily as eyewitness testimony (but there are plenty of nonfiction books for that), or will scour them for material to buttress an argument about what exactly Serge believed politically and when. And some will let Serge’s reputation for “ethical heroism” (however deserved) blind them to the complexities of his fiction, which involves—like all ambitious literature—ambiguity, ambivalence, and contradiction. Whatever the merit of these perspectives on Serge, they leave little room for the pleasures and provocations of the novels read on their own terms—novels in which light and lightness appear at unlikely junctures, as when some old Bolsheviks who have gathered secretly in the woods to discuss the degeneration of the party and their own imminent destruction conclude their conversation with a snowball fight:

Kiril, suddenly dropping the burden of his years, jumped back, raised his arm—and the hard snowball he had just finished making struck an astonished Philippov square on the chest. “Defend yourself, I attack,” Kiril cried gaily and, his eyes laughing, his beard askew, he grabbed up handfuls of snow. “Son of a seacook,” Philippov shouted, transfigured. And they began to fight like two schoolboys. They leaped, laughed, sank into snow up to their waists, hid behind trees to make their ammunition and take aim before they let fly. Something of the nimbleness of their boyhood came back to them, they shouted joyous “ughs,” shielded their faces with their elbows, gasped for breath. Wladek stood where he was, firmly planted, methodically making snowballs to catch Rublev from the flank, laughing until the tears came to his eyes, showering him with abuse: “Take that, you theoretician, you moralist, to hell with you,” and never once hitting him…

Adam Hochschild notes this passage from The Case of Comrade Tulayev as an example of how Serge “never lets his intense political commitment blind him to life’s humor and paradox, its sensuality and beauty.” That’s right, but what I’ve been trying to suggest is how, in the novels, questions of political commitment and questions of sensuality can’t be separated out. It’s not that Serge was committed to a vision of History but stopped to smell the flowers—it’s that the question of how sensual particulars vibrate with the “great ensemble of life,” how you experience the latter “by virtue” of the former, is a central political question in the fiction. When Serge’s characters reckon with how life after the party, even one “unhinged by suspicion,” might be “barren—like masturbation,” what is the relationship between sensuality, political commitment, and blindness?

And when Serge describes the attempt both to see individuals in their particularity and to see through them to the transpersonal “soul,” the question of the relation of the sensual and the political is posed but not answered. (Who goes to art for answers?) Even the snowball fight above seems to me to be more—and more unsettling—than a flash of joie de vivre among those marked for destruction, although it’s certainly that. Are these old men enjoying a moment outside of their fate, outside of politics, rooted in nature, or playfully renewing a warrior spirit that will give them the courage to accept their deaths as party sacrifices? The moral is unclear to me (take that, you moralist), which is part of why the scene remains so vivid.

This Issue

January 19, 2023

Dress Rehearsal

When Diversity Matters

The Instrumentalist

-

1

“His political and geographical journey went from Belgian second international socialism to French anarchist individualism, from Spanish anarcho-syndicalism to Bolshevik revolutionary Marxism,” is Susan Weissman’s summary of Serge’s political evolution. Her Victor Serge: The Course Is Set on Hope (Verso, 2001) is the best political biography. ↩

-

2

While Berger’s larger point about Serge seems right to me, it must be said that women in most of his books appear very stereotypical indeed. “In this entirely men-centered society of challenge—and ordeal, and sacrifice—women barely exist,” as Sontag puts it, “at least not positively, except through being the love objects or wards of very busy men.” There are exceptions to this—the most important being the character of Daria in Unforgiving Years. ↩