Anytime the likes of Donald Trump, Greg Abbott, or Tucker Carlson begin inveighing against “caravans” of Central American “aliens” massing at the southern border and set on “invading” the United States, I recall a phrase of V.S. Naipaul’s. When in the late 1960s the British Tory politician Enoch Powell complained of white Britons being “made strangers in their own country” and immigrants from former colonies being “elevated into a privileged or special class,” the future Nobel laureate—a Caribbean-born descendant of indentured servants brought from India—had the perfect rejoinder: “We wouldn’t be here if you hadn’t been there.”

Harsh Times, Mario Vargas Llosa’s nineteenth novel, is a similarly blunt corrective. What the MAGA crowd forgets, but Vargas Llosa remembers and effectively portrays, is that decades of American imperial meddling in what used to be called our “backyard” have contributed greatly to the exodus of desperate people from Central America, a region wracked by gang warfare, militarism, corruption, poverty, drug trafficking, climate instability, disease, and despair. It is impossible, for example, to talk honestly about the MS-13 international crime syndicate and the murders its members have committed on Long Island—a favorite subject of Trump’s—without acknowledging that the gang’s founders were Salvadoran refugees in California driven from their country by a violently repressive, military-dominated government advised and equipped by the United States during a twelve-year civil war. At the CIA, they call that blowback.

All seven of the nations that occupy the isthmus between Mexico and Colombia have had to bear the consequences of American intervention in their domestic affairs, but it can be argued that none has suffered more than Guatemala. The most populous country in the region, with 18.5 million people, it endured both an American-organized coup that is the main subject of Harsh Times and the civil war that followed—a conflict that lasted more than thirty-five years, resulted in the death or forced disappearance of some 200,000 people, most of them of indigenous descent, and drove millions more into flight or exile, many of them to the United States. After the war ended in 1996, a government commission acknowledged that military and police forces originally trained and financed by the United States had committed genocide against Guatemala’s majority-Maya population.

The quarter-century since has been only marginally better, as former combatants who were demobilized but not disarmed regrouped into criminal cartels. The winner of the first postwar presidential election was charged with laundering $70 million through American banks and agreed to a plea deal with federal prosecutors on a lesser charge of accepting a bribe. His successors have been a motley group. They range from a comedian who promised to eradicate corruption but was soon under investigation for taking campaign donations from drug traffickers and overlooking bribe-taking and money-laundering by his brother and son, to a retired general and former director of military intelligence who was elected on a tough-on-crime platform but has been credibly accused of being involved in atrocities during the civil war. So it is only natural for Vargas Llosa to grieve for the path Guatemala might have taken had the two Uniteds—the United States and the United Fruit Company—not intervened, in a fit of cold war paranoia, to overthrow a reformist, popularly elected president, Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, in June 1954.

Harsh Times begins in New York in the 1940s, with the first encounter of the two men whom Vargas Llosa, boldly but questionably, describes as having “the greatest influence over the destiny of Guatemala and, in a way, over the entirety of Central America in the twentieth century”: Samuel Zemurray, the president of United Fruit, and Edward Bernays, now regarded as the father of modern public relations. “Seems we have a bad reputation in the United States and Central America,” Zemurray explains to Bernays, asking for advice. Bernays signs on not only to devise clever campaigns to stimulate consumption of bananas in the US but also to “clean up the company’s image and garner it support and influence in the political world.”

At this point I grimaced and said to myself, “Oh no, here we go again.” The 1954 coup has been so extensively written about—the best nonfiction account is still Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer’s Bitter Fruit (1982)—and is now so standard a part of college curricula that one might wonder if anything new can be said about it. But Vargas Llosa is too canny to fall into the trap of predictability: rather than focus on well-known figures like Árbenz and the Dulles brothers, John and Allen—the first Dwight Eisenhower’s secretary of state, the second his CIA director, and both former partners at Sullivan & Cromwell, the law firm that represented United Fruit—he elevates to the main narrative others who are usually considered secondary, if even that.

Advertisement

That makes Harsh Times more a novel about Árbenz’s successor, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, than the coup itself, and when Vargas Llosa relates the events leading up to and following it, he does so largely from the point of view of Castillo Armas and those around him. Árbenz and his reformist predecessor, the philosophy professor Juan José Arévalo, are not ignored, but here Vargas Llosa is like Tom Stoppard shifting the focus of Hamlet from the Prince of Denmark to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. In place of the Dulles brothers we get a CIA operative known as “the gringo whose name wasn’t Mike,” and in place of business magnates we get sympathetic portraits of the people they exploit and oppress.

Like any Latin American novelist interested in politics, Vargas Llosa has at various times throughout his long career felt compelled to write about the military, and it is fascinating to see how his attitudes have evolved. Exactly sixty years ago, he exploded onto the literary scene with his first novel, The Time of the Hero, a Faulkner- and Flaubert-influenced tale of murder, corruption, and dishonesty among military school cadets. First published in Spain, the book was considered so scabrous that copies were burned when they reached his native Peru. A decade later, his tone had shifted to one of mockery: the protagonist of Captain Pantoja and the Special Service (1973), probably the most comic of his novels, is a punctilious army officer assigned to supervise a detachment of prostitutes who service soldiers in the Peruvian Amazon, and the book satirizes bureaucratic jargon, hierarchy, and procedures to great effect.

In Harsh Times, though, Vargas Llosa adopts a more measured tone toward both individual soldiers and the Guatemalan military as an institution, which a South Carolina–born American ambassador dismisses as merely a bunch of “Indians in uniform.” Árbenz, an army colonel, not surprisingly comes off best, portrayed as sincere, dedicated to ending Guatemala’s backwardness, and bewildered by Washington’s hostility. “Weren’t the spirits of free enterprise, of open competition and private property the very things his Agrarian Reform law wished to promote?” he asks himself. “He had naively believed the United States would be the greatest advocate for his policy of modernizing Guatemala and pulling it out of the Stone Age.”

Perhaps the most affecting chapter in Harsh Times recounts the brief life of an idealistic military cadet of humble origins named Crispín Carrasquilla, “a good kid, artless, maybe a touch dim, easy to make friends with.” Initially indifferent to politics, which he regards “as something distant, matters that didn’t concern him,” he is disgusted when Castillo Armas and his “herd of undisciplined grifters with ragtag armaments” seize power, ends up being killed in a clash between cadets and the mercenary “gang of thugs,” and is “buried with other victims from that revolutionary ploy in a common grave, the location of which would be kept secret to prevent it from becoming a place of pilgrimage for communists in the future.” This passage in particular will ring true to anyone who has spent any time talking with Latin American conscripts and noncoms:

His ideas were naturally confused, more emotional than rational, and they mingled love (for the land of his birth, for his comrades, and for his army, all of which, for him, were shrouded in sanctity) and hatred, even rage against anyone willing to let political interests compel them to attack their own country.

But even Castillo Armas, with his silly Hitler mustache and penchant for crossing his arms à la Mussolini, is treated with a certain sympathy. He is insecure and close-minded, but he is given an interior life and becomes a figure more to be pitied than scorned, having probably been selected by the CIA as Árbenz’s successor because “his skin and facial features were those of an Indian rather than a mestizo,” and he thus appeared to be more “docile and malleable” than other possibilities. Vargas Llosa also draws a sharp contrast between Árbenz, a golden boy of Swiss descent who from the start “stood out for his good looks, his academic brilliance, and his athletic achievements,” and Castillo Armas, whose indigenous mother is described as “a humble woman in a huipil embroidered with a quetzal and a long skirt held up with a rustic sash.”

Castillo Armas, “so thin you could see the bones poking through his face and arms,” had envied Árbenz as the embodiment of everything that he was not and could never be “since they were cadets at the Politécnica” as teenagers, Vargas Llosa writes.

Back then, it was for personal reasons: Árbenz was white, handsome, and successful, whereas Castillo Armas was poor, a bastard, his Indian features a sign of his humble origins. Then Árbenz had married María Vilanova, a beautiful, rich Salvadoran, while his own wife, Odilia Palomo, was a homely teacher as destitute as he.

When Vargas Llosa won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010, the Nobel committee singled out “his cartography of structures of power” as one of the most distinctive characteristics of his work. Here we see that gift on full display, as two powerful social and political structures collide and clash. Árbenz is a beneficiary of Guatemala’s highly stratified class structure but wants to implement progressive measures to benefit the impoverished Mayan masses. Castillo Armas has emerged from the class that would benefit most from those policies, but he takes refuge in the military, a tool of the most reactionary elements of the elite from which his rival comes. In this intersection lies tragedy, not just for the two men involved but for an entire nation.

Advertisement

Another way of looking at Harsh Times is to consider it an extension or reframing of The Feast of the Goat (2000), Vargas Llosa’s novel about the 1961 assassination of General Rafael Trujillo, the American-trained dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic for thirty years. The two novels share overlapping themes and characters, notably Trujillo and his sinister intelligence and security chief, Johnny Abbes García, but the similarities do not stop there. In the earlier novel, Vargas Llosa often presumes to imagine the thoughts of real historical characters, roaming the darkest recesses of Trujillo’s mind, and he employs the same technique in Harsh Times. That is especially true of Abbes García, who seems even more vile and menacing in the new novel than before, with his “glacial, cutting tone, his vicious, unshifting stare,” and he gets a comeuppance that must have given Vargas Llosa great satisfaction to write.

In interviews in Spanish-language media, Vargas Llosa has explained that the germ of Harsh Times came from a conversation at a dinner party he attended in the Dominican Republic, where another guest alerted him to a little-explored connection between Trujillo and Castillo Armas, who had sought the Dominican dictator’s assistance in advance of the coup. Trujillo, hoping to curry favor with Washington, agreed. But Vargas Llosa takes things a step further, into speculative territory. Officially, Castillo Armas was killed in 1957 by a member of the presidential guard who secretly harbored leftist sympathies. But Vargas Llosa would have us believe that Trujillo ordered the assassination because Castillo Armas had proved insufficiently grateful, even insulting Trujillo’s family in private conversations, and that Abbes García carried out the killing. It’s a plausible scenario, especially since Trujillo tried to have the president of Venezuela killed, but unproven. Or as a secondary character says, referring to the same mystery: “Just as with so much else in Guatemala’s history, it’s likely we’ll never know the answer.”

Trujillo’s presence in the novel is a vivid reminder that Guatemala’s 1954 coup was not just an American operation. Dictators throughout the Caribbean basin, many of them marionettes of United Fruit, were also deeply involved. Anastasio Somoza—not the one ousted by the Sandinistas in 1979 after Jimmy Carter withdrew his support, but his father, of whom FDR is reported to have said, “he may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch”—gets a cameo, as do the leaders of El Salvador and Honduras, whose president at the time of the Guatemalan coup, Juan Manuel Gálvez, had for many years been a lawyer for United Fruit. It was an interlocking system of banana republics, subjugated to the interests of a single American corporation, that would continue for many years. Vargas Llosa doesn’t mention it, but when the CIA tried to overthrow Fidel Castro in 1961, many Bay of Pigs combatants trained in Guatemala and then embarked from Nicaragua.

Vargas Llosa is not the first Latin American, or even the first Latin American Nobel laureate, to write about United Fruit—known informally in the region as La Frutera or the Octopus—and its enormous depredations. One of the most memorable moments in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude is his description of the Banana Massacre of December 1928, which came in response to a monthlong strike by United Fruit’s employees in Colombia demanding higher wages and better working conditions. But even before that, the Guatemalan Miguel Ángel Asturias, mentioned briefly in Harsh Times, had written a Banana Trilogy of novels between 1950 and 1960 (Strong Wind, The Green Pope, and The Eyes of the Interred), as well as a lacerating short-story collection, Week-end en Guatemala, which deals directly with the coup that toppled Árbenz and unfortunately is still not available in English, more than sixty-five years after it was published. “Do you not see the things going on around you? Better to call them novels!” is Asturias’s anguished epigraph.

Harsh Times differs from these works in two fundamental ways. First, it eschews any overt form of fantasy, whether surrealism (Asturias’s forte, a result of having spent the 1920s in Paris consorting with André Breton, Paul Valéry, and their circle) or magical realism, the hallmark of the Boom generation of Latin American writers of which Vargas Llosa was a part in his youth. But even more important, and somewhat unexpected in a novel that takes place mostly in the 1950s, is its timeliness. Harsh Times is not going to be remembered as one of Vargas Llosa’s major works, and it doesn’t rise to the level of Conversation in the Cathedral (1969) or The War of the End of the World (1981) or even his Andean novels of the 1980s and 1990s. But looking at the overthrow of Árbenz from Vargas Llosa’s vantage point, we can see that it was an early expression of some of the worst features of today’s politics, from the fake news propagated by a CIA radio station operating from Honduras to the arrogant sense of impunity that prevails when an imperial power operates in the “near abroad.”

Almost all the leading characters in Harsh Times appear under their real names, a notable exception being a woman nicknamed Miss Guatemala because of her beauty, who essentially steals the story from the large cast of presidents, generals, diplomats, CIA types, and thugs. Called Marta Borrero Parra in the novel, she proves to be even more duplicitous and scheming than they are: disowned by her family after she gets pregnant at fifteen, she becomes the mistress first of Castillo Armas and then, after his death, of Abbes García. “An intrepid woman, hardened by a life in which she had survived terrible things” is how Vargas Llosa describes her, too gallant to say she may also have perpetrated terrible things.

In reality, the woman’s name is Gloria Bolaños Pons, and in a fictionalized account of an interview with her late in the book, Vargas Llosa provides a reason why he may have disguised her. “Don’t bother sending me your book when it comes out, Mario,” she tells him. “I will absolutely not be reading it. But I warn you, my lawyers will.” Or perhaps no interview ever took place: Vargas Llosa has her living near Langley, Virginia, close to CIA headquarters, though she actually lives near Fort Lauderdale and even in her mid-eighties maintains a very active Twitter account. Still a fierce reactionary, both she and her fictional equivalent are big fans of Donald Trump and recruit “Latino voters for the Republicans every election year,” which brings the novel full circle.

Writing history in the form of a novel offers enormous leeway, but there are moments when Vargas Llosa either leaves out crucial details or, in his zeal to entertain the reader, adds colorful specifics that seem dubious. Zemurray couldn’t have “discovered the banana tree in the forests of Central America” because he had already encountered the then-exotic fruit in Alabama in the 1890s as a newly arrived immigrant from Bessarabia. And Vargas Llosa’s contention that it was Bernays “who brought to the United States the Brazilian singer and dancer Carmen Miranda,” she of the tutti-frutti hat, as a way to promote banana consumption would be droll if true. But it is contradicted by Ruy Castro’s authoritative biography Carmen (2005), which makes it clear that the Broadway impresario Lee Shubert convinced her to come to New York after seeing her perform in Rio.

On a more substantial matter, Vargas Llosa’s admiration for Árbenz leads him to play down an episode that raises uncomfortable questions. Árbenz served as his predecessor’s minister of defense but quarreled constantly with the chief of the army, Colonel Francisco Arana, who also had presidential ambitions. On July 18, 1949, amid rumors that he was planning a coup, Arana was killed during a highway ambush and gun battle whose objective may or may not have been to arrest him. Vargas Llosa briefly mentions this but also, in contrast to Schlesinger and Kinzer’s more neutral account, ignores evidence that ties people close to Árbenz, such as his wife’s chauffeur, to the killing. “While we cannot be sure who made the decision to kill Arana, it was done in the interests of Arbenz,” concluded the American historian Ronald Schneider.

I also wish that Vargas Llosa had been more generous in his acknowledgments, which occupy only half a page. He thanks the Hemeroteca Nacional de Guatemala for granting him access to the newspapers and magazines in its collection and also expresses gratitude to the country’s leading university for “the extraordinary favor of allowing me to work in their excellent library.” But he mentions none of the books he consulted there, or any other resources, for that matter. This has long been a sore point among journalists who preceded Vargas Llosa in some of the places he writes about; in the case of The Feast of the Goat it even provoked the late Bernard Diederich, dean of Caribbean reporters, to claim that Vargas Llosa had plagiarized his biography Trujillo: Death of the Goat (1978).

Harsh Times is dedicated to three prominent Dominican writers, one of whom, Tony Raful, gets a late-chapter shout-out for his book The Rhapsody of Crime: Trujillo vs. Castillo Armas (2017), which Vargas Llosa presumably read. But I recall first reading much of the information here about Zemurray and Bernays in a pair of biographies: Rich Cohen’s The Fish That Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King (2013) and Larry Tye’s The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and the Birth of Public Relations (1998). To be clear: Vargas Llosa has not plagiarized either. But he does seem to have benefited from the archival work of the two American journalists, and it would have been elegant of him, a man who values that quality in everything from his dress to his prose, to let readers know that. I guess it all comes down to whether novelists, like spokesmen for US intelligence agencies, have the right not to reveal “sources and methods.”

Adrian Nathan West’s translation generally captures the flavor of Vargas Llosa’s late style, which is more direct and less embellished than his earlier writing. But a few of his choices seem questionable. I was surprised to see a gathering at which Castillo Armas listens to his finance minister and various economists called a “reunion,” not a “meeting”; the Spanish word reunión, which Vargas Llosa used, is a false cognate here. And there is an erroneous, and thus quite confusing, reference to “two parties affiliated with the Árbenz government” that were actually affiliated with Arévalo, a mistake that does not appear in the original Spanish version.

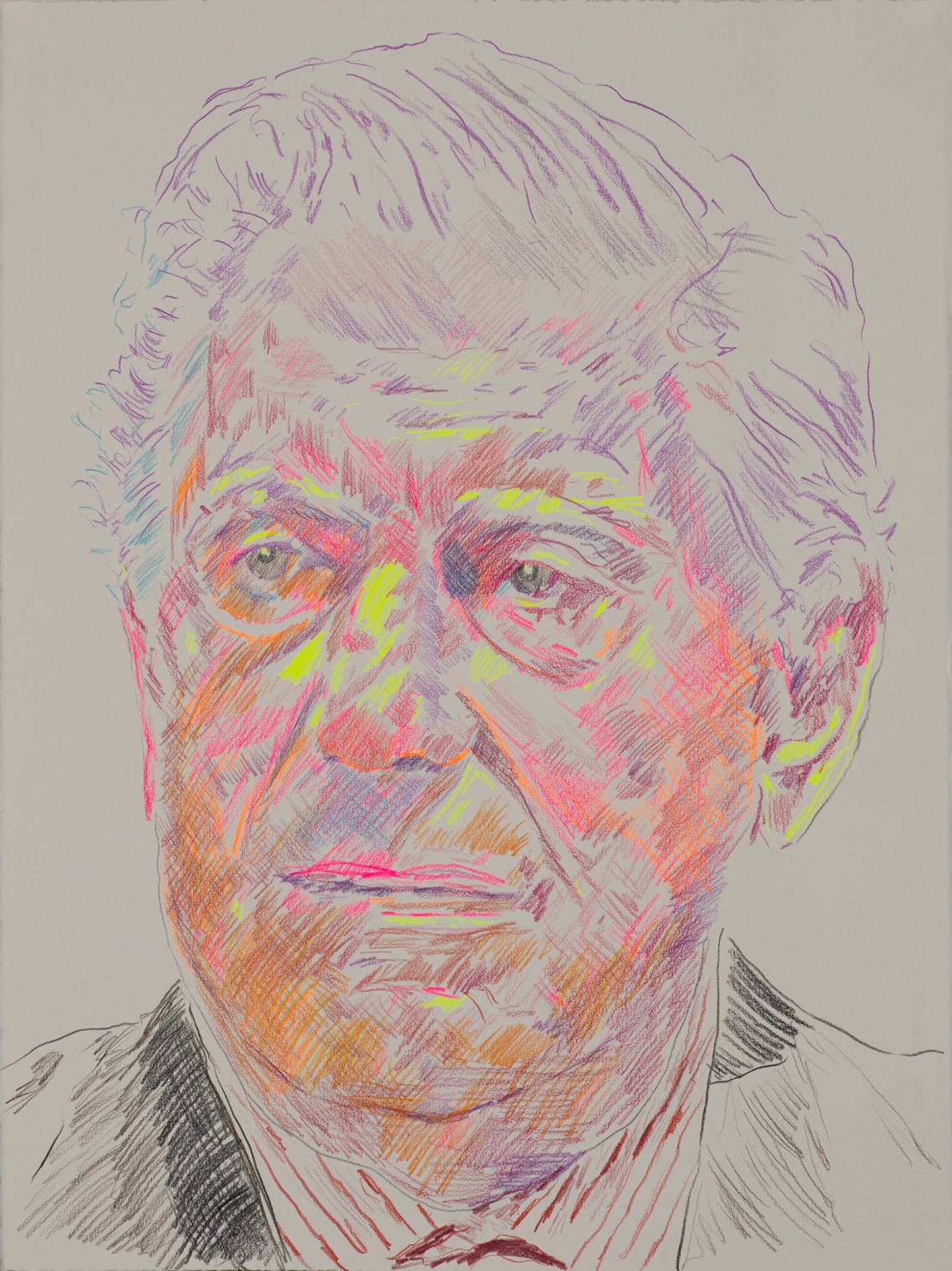

Now eighty-six and living mostly in Madrid, Vargas Llosa has moved steadily rightward in his politics as he has aged: in the 2021 presidential election in Chile he endorsed a hard-right candidate who defends the Pinochet dictatorship and talked of digging a ditch to prevent Bolivians from crossing their shared border. Vargas Llosa has also acquired both Spanish citizenship and a hereditary royal title and is now a marquess, with his own coat of arms; as a celebrity member of the peerage, he is fodder for Spain’s gossip magazines, where he is frequently pictured at the side of his companion, the socialite and former model Isabel Preysler, an ex-wife of Julio Iglesias.

This all sounds quite frivolous, and probably is. But Vargas Llosa, who in The Call of the Tribe (2018) described his personal ideological migration from Cuban-style socialism to a classic nineteenth-century liberalism with overtones of Hayekian libertarianism, has lost neither his sympathy for the underdog nor his eye for the telling detail. Throughout Harsh Times his compassion remains with Guatemala’s perpetually oppressed indigenous majority, perhaps a reflection of his own roots in Peru, where the descendants of the Incas face similar barriers and a structural racism that has been in place for centuries. In one wonderfully atmospheric vignette, a pair of conspirators, both of whom would consider themselves white, sit drinking rum in an “empty and forlorn” brothel as

a circumspect Indian was sweeping the scattered sawdust from the floor, gathering it in his hands, and dumping it into a plastic bag. He was a small, rickety creature, and he hadn’t once turned to look at them. He was barefoot, and his cotton shirt, torn and mended in places, revealed patches of dark skin inside. The owner had put on a stack of records, a collection of boleros sung by Leo Marini.

At the very end of the novel, Vargas Llosa steps back from his tale to contemplate the real-world consequences of America’s folly. “The history of Cuba might have been different had the United States accepted the modernization and democratization of Guatemala that Arévalo and Árbenz attempted to carry out,” he writes, referring to the theory that the coup radicalized Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, who was in Guatemala when it occurred. “When all is said and done, the North American invasion of Guatemala held up the continent’s democratization for decades at the cost of thousands of lives.”

Mercifully, Harsh Times comes to an end in the early 1960s, before the worst of that carnage. But Guatemala’s civil war is foreshadowed when a disgraced military officer just out of prison reflects on the changes that have occurred while he was locked up:

There were guerrillas in Petén and in the east, assassinations, kidnappings, curfews, so-called expropriations of banks. Crime often masqueraded as politics. And then, the military coups came one after the other. Life was more dangerous than before, for everyone. Which was also bad for business.

Speaking of business, United Fruit has twice changed its name and is now known as Chiquita Brands International, a Switzerland-based purveyor of sustainably grown bananas and Rainforest Alliance–certified pineapples—part of what seems a very twenty-first-century attempt at expiation that has helped ensure annual revenues of more than $3 billion. The last time I had any contact with La Frutera was in 1996, when it was trying to evict employees in Honduras from land the company hoped to sell to ranchers and developers. Meanwhile, the descendants of such workers and others who have fled northward for similar reasons have been subjected to a name change too: once considered refugees, they are now “migrants,” a word that bleaches away the political component of what they have been through. Harsh times indeed.