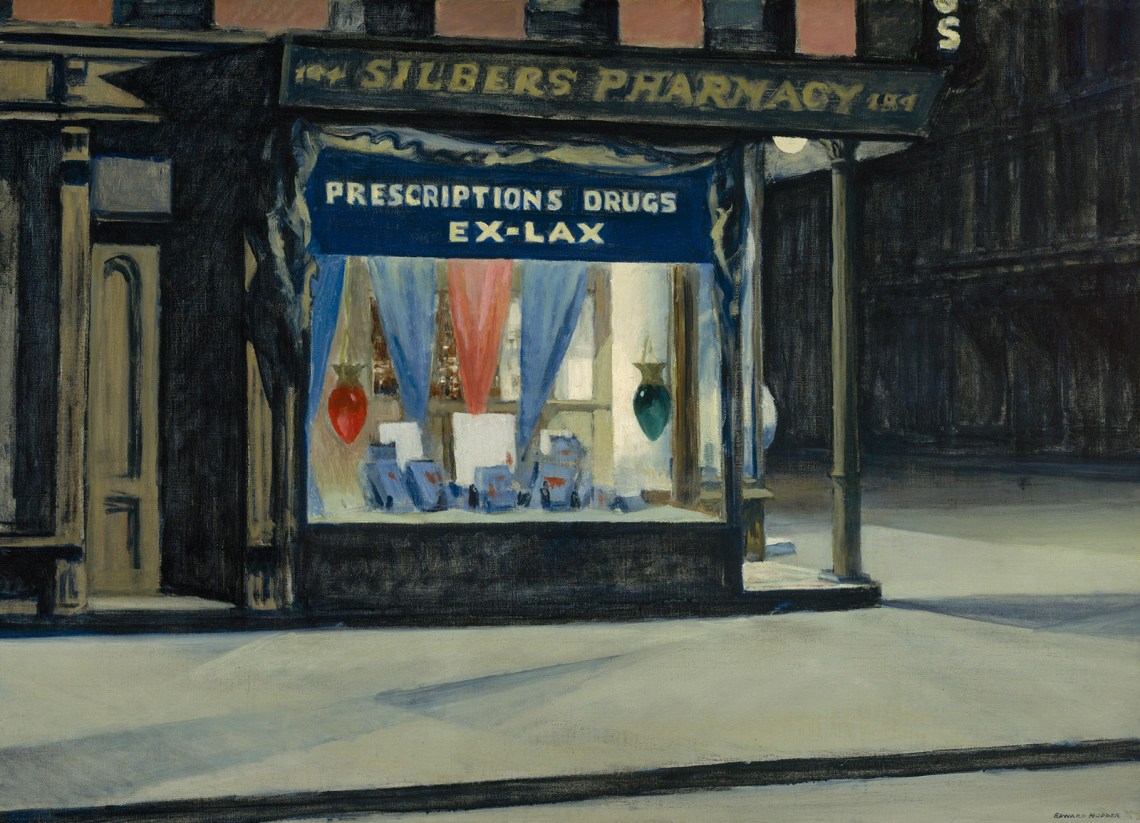

“Edward Hopper’s New York,” the sumptuous exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, gives us one more chance to retire—at least for a decent interval—those once glamorous words that have come to dominate, and increasingly suffocate, our experience of Hopper’s paintings: alienation, loneliness, voyeurism, the uncanny. Such neon abstractions give us the illusion that we have dispelled the puzzlement we often feel in front of Hopper’s strange compositions. What they actually do is give us license to stop looking at the pictures, causing us to miss crucial aspects of his achievement, such as his pervasive and peculiar sense of humor. A painter who features an ad for Ex-Lax in a moody nocturne of a corner drugstore isn’t just concerned with alienation.

It is hardly news that New York was important to the painter of such classic urban scenes as Nighthawks (1942) and Early Sunday Morning (1930). Aside from early trips to Paris, regular summers on Cape Cod (where he built a house), and a couple of trips west, Hopper derived much of his subject matter from the city. As a teenager, he traveled down from his hometown of Nyack (where that other New York obsessive of enclosed rooms, Joseph Cornell, also grew up) to study at art schools in the city. He moved there in 1908 but didn’t sell his first painting until 1913, at the Armory Show, when he was thirty-one. He sold his second ten years later, meanwhile supporting himself with commercial work for trade magazines.

By September 1913 Hopper was living at 3 Washington Square, one of the handsome brick buildings on the square’s north side, known as “the Row.” The building was broken up into artists’ studios: Thomas Eakins had painted there, and Rockwell Kent overlapped with Hopper; Willa Cather set a romantic encounter between a painter and his model on a Washington Square roof. The building, a walkup, had no central heating, and tenants shared a bathroom. Despite such spartan arrangements and Hopper’s own financial success (including a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1933), he lived at the same address for his entire working life, along with his fellow artist, business manager, muse, and primary model, Josephine (Jo), whom he married in 1924.

A show devoted to Hopper’s New York is bound to emphasize the representational side of his work: bridges, street corners, shop windows, theaters, concrete walls. A cluster of deft watercolors of his rooftop—the bricks seem porous and the skylights sprinkled with dust—captures a ghostly world reminiscent of De Chirico. It has seemed to some viewers that Hopper, who fought to prevent NYU from evicting artists from the historic building in which he lived, is nostalgic for a lost New York. But what Hopper really loved—loved as an artist—was the clash of old and new, the quirky Greek Revival rubbing up against the sleek and featureless modern. Paris, he wrote with slight disdain, was “a very graceful and beautiful city, almost too formal and sweet to the taste after the raw disorder of New York.”

In an article published in 1928, Hopper reveled in “our native architecture…with its hideous beauty, its fantastic roofs, pseudo-Gothic, French Mansard, Colonial…with eye-searing color or delicate harmonies of faded paint, shouldering one another along interminable streets.” That last phrase hints at something beyond the merely mimetic in his work, as in his 1928 painting From Williamsburg Bridge, where the frieze of mismatched façades evokes a quirky family jostling one another for the attention of the camera.

We can’t help but feel that realism doesn’t exhaust what we are looking at in such pictures. Hopper deplored his generation’s documentary attention to the “American scene”—a phrase, he said, that “has been applied to American painters who definitely tried very hard to be American, and I never did.” He rejected, sometimes in surprisingly oracular terms, the notion that his work aspired primarily to realism. “The dreamer and the mystic must create a reality that you can walk around in, exist and breathe in,” he wrote in his journal “Notes on Painting,” one of his rare attempts to capture in words what he was up to as an artist. In a similar vein, he called for “a base of realistic art from which fantasy can grow.” To vary Marianne Moore’s famous definition of poetry, Hopper gives us real gardens with imaginary toads in them.

The first task of “Edward Hopper’s New York” is to magnify the significance of the city for Hopper, which entails minimizing the impact of Paris. There is a symptomatic reference early in the catalog to Hopper’s “three short stays in Paris,” yet a footnote to the passage describes them more accurately as “three extended visits: October 1906–June 1907; March–August 1909; and May–July 1910.” It’s true that Hopper claimed, as quoted in the catalog, “Paris had no great or immediate impact on me.” It’s also true that he told an interviewer, “It took me ten years to get over Europe.”

Advertisement

The evidence on the Whitney’s walls suggests that the Parisian influence lingered. Already in Paris he had settled on the expressive possibilities of urban architecture largely devoid of people.1 Hopper lived on the Left Bank near the Pont des Arts, the subject of an impressive painting from his 1907 sojourn. The pedestrian bridge extends horizontally across the canvas, spanning the empty quay on one side and the spectral structure of the Louvre—gray, peripheral, partially hidden by the bridge—on the other. The drama is in the structural rhythms of quay, bridge, water, and sky.

Blackwell’s Island (1911), the first of several paintings incorporating the Queensboro Bridge (the entrance was not far from his East 59th Street apartment at the time), shows Hopper working the same territory in the same gray-red-white-black tonality: bridge, water, spectral building (a little gothic house beneath the bridge, where the warden for the penitentiary on what’s now called Roosevelt Island lived). By the time Hopper takes up the subject again in a painting of the same name from 1928, the bridge is reduced to a tiny sliver at the righthand margin, and a new subject has emerged: a frieze of buildings in radically different architectural styles.

What Hopper discovered was that when the people are gone, the buildings come to life. In yet another painting of 1928, the marvelous Manhattan Bridge Loop, a barely discernible pedestrian vanishes into the shadow cast by the bridge railing to the left. The painting’s real subject is the tall lamppost on the opposite side; the illuminated bulb is seen in such a way that it becomes part of the skyline—a mélange of older red brick, bland high-rises, and clustered water towers. The lamppost (featured on the cover of the exhibition catalog) has an almost human presence. Lest we think we’re reading too much into such paintings, it’s worth remembering that Jo referred to a painting of a lone Beaux Arts building spared demolition as Hopper’s self-portrait. As Baudelaire wrote in his own evocation of Paris changing under the plans of the Baron Haussmann, “Tout pour moi devient allégorie.”

Early Sunday Morning, along with Manhattan Bridge Loop, is part of a breathtaking sequence at the Whitney of five monumental horizontal paintings, panoramic and nearly identical in size, that Hopper completed between 1928 and 1935. Early Sunday Morning—acquired by the Whitney soon after Hopper finished it, during the early months of the Great Depression—was featured at the museum’s opening in its original location, on 8th Street, in November 1931. It remains one of the museum’s signature works.

The viewer’s first impression of Early Sunday Morning, as of so many of Hopper’s best-known paintings, is of horizontal rows: storefronts, windows, eaves, shadows cast by the morning sun, a strip of gray sidewalk below, and a strip of powder-blue sky above. “I just never cared for the vertical,” Hopper once remarked. He said he found the buildings on Seventh Avenue; he also said that putting “Sunday” in the title, probably to explain why the street was empty, wasn’t his idea. In a catalog essay, David Crane argues that Hopper found inspiration in Jo Mielziner’s modernist stage design of a play named Street Scene that the Hoppers attended in early 1929. “Hopper’s iconic painting…bears a distinct resemblance to Mielziner’s design,” Crane writes, noting various parallels such as “brownstone storefronts…from edge to edge,” a concrete sidewalk, and the like. A letter from Jo Hopper, a former amateur actor, mentions “that Street Scene set we loved so much.”

Of course, we can see that Hopper’s pictures sometimes resemble movie stills (Hitchcock in particular) or theater sets, just as we can see that he painted the exteriors and interiors of theaters. But the Whitney installation has way too many vintage photographs, along with ticket stubs and other documentation of the plays the Hoppers saw. The Piranesi-like swirl of The Sheridan Theatre (1937) gains nothing from juxtaposition with photographs of the original theater. The glamorous New York Movie (1939), with its pensive usher (modeled by Jo) seeking refuge in an alcove near a stairway as a black-and-white film plays to a nearly empty venue, is slotted among a thicket of theater paraphernalia. The painting, like the usher, needs more room to breathe.

A mysterious detail in Early Sunday Morning has taken commentary in a different direction. The strip of blue sky along the upper edge is interrupted by a gray-black square in the corner. It has come to seem obvious to art historians that the square is part of a sleek new building rising above the nineteenth-century row of brick buildings. “Hopper made Early Sunday Morning at a historic moment in the city’s race to the sky,” the Whitney curator Kim Conaty writes. “As the Chrysler Building neared completion, its reign as the tallest building in the world was already destined to be short-lived, since construction was soon set to begin on the Empire State Building.”

Advertisement

It has also come to seem obvious that Hopper, with his little square, was trying to register some kind of protest against the tall buildings that increasingly menaced an earlier New York. Conaty refers to the “looming dark rectangle hovering over a low-slung building,” while Crane invokes “the implied threat of the high-rise hinted at in the corner of Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning.” That the Hoppers were involved for years in trying to preserve the nineteenth-century character of Washington Square makes such an interpretation seem all the more plausible. In The City (1927), a tall, featureless white building, presumably 1 Fifth Avenue, towers above Washington Square.

But Hopper is a poor candidate for an antigentrification activist. A lifelong conservative Republican, he was vehemently opposed to the New Deal. “Anyone but that jackass,” he wrote of FDR’s 1936 reelection campaign, “even Shirley Temple.” His effort to preserve his Washington Square studio building was couched in elitist terms, evoking the many distinguished artists and writers, including Edmund Wilson, who had lived there. It’s hard to imagine Hopper coming to the defense of poor residents in need of housing. Conaty notes that Hopper “left out the city’s crowds of people and its booming immigrant population” in his work, amid the “nearly uniform whiteness of his figures, when they appear at all.”

When Hopper did include human figures, they often seem outgrowths of their architectural surroundings. Room in New York (1932), with its window view of a couple in an apartment, has a heavy architectural framing. A massive Doric column next to the stolid man reading a newspaper in a plush armchair establishes a metaphorical equation. A wooden door that seems impossibly tall, cut off by the upper edge of the canvas, separates him from a woman in red seated at a piano. The woman, her back turned (petulantly?) to the man, plays a single note on the piano. The painting reeks of anecdote, in the oblique, unspecified way of certain paintings by Degas. Is the couple, in formal evening clothes, about to go out, or have they just returned? Is the struck piano meant to get the man’s attention, if only by annoying him? I’m pretty sure Hopper, who rejected anecdotal interpretations across the board, didn’t have answers to such questions.

And yet it’s hard not to read such paintings as partial stand-ins for the Hoppers, especially since Jo posed for most of them, including a series of bleak nudes in bedrooms lit by the morning sun. “As a companion E.H. lives to keep his nose in printed matter,” she wrote in 1946. “Any printed matter.” Talking to her husband, she said, was “like dropping a stone in a well except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom.”

The marriage was durable. According to Gail Levin’s “intimate biography” of Hopper, which draws its intimacy primarily from Jo’s diaries, it was also abusive. Among other tensions in the marriage, Hopper didn’t take Jo’s painting seriously. In describing their battles with each other, both resorted to animal metaphors. “Living with one woman is like living with two or three tigers,” Hopper said. Jo said life with Hopper, six foot five to her barely five feet, was punctuated with “violence à la gorilla.” Once, driving through Yellowstone, Jo tried to stop the car, which Hopper was driving, so that she could pat the bears. Recalling the result in her journal, she confessed that she “always found tall men exciting, not when they use that extra span of arm length to swat me tho.” All marriages are mysterious, but what we know of this one—“violent” and “claustrophobic” in Kirsty Bell’s account—leaves a disturbing aftertaste.

In his final painting, Two Comedians (1966), completed when Hopper was eighty-three, a Hopper-like couple dressed in theatrical white (he in tricorn hat and tights, she in a mobcap and ruff) hold hands as they take a formal bow on a proscenium stage, with some artificial greenery on one side. “Do you notice how artificial trees look at night?” Hopper asked an interviewer a couple of years earlier. “Trees look like theater at night.” The picture—in which, Bell suggests, Hopper “casts a rueful eye back on their life together”—seems to register the element of role-playing in their life, with perhaps the hope that it was more comedy than tragedy. The following year, Hopper died while seated in his studio; ten months later, Jo was hospitalized and died soon after. The Whitney inherited the contents of the studio—including more than two hundred paintings—and NYU got its wish in taking over the building.2

During his final years, Hopper’s work, as in Two Comedians, took on an imaginative and improvisatory freedom, as though he were testing the limits of his mantra, a “realistic art from which fantasy can grow.” The fantasy was often retrospective. During the summer of 1925 he and Jo, both in their early forties and married the previous year, had traveled by train to Santa Fe, a standard destination for New York artists in search of exotic subjects. Hopper was not inspired by weathered adobe or Native American dances. The mountains were “like sand hills,” he grumpily reported. On a later trip west, he deemed the deserts and canyons “too impersonal,” while Yosemite lacked “clearness of atmosphere.”

Lingering impressions of the West did give Hopper one of his strangest—and greatest—paintings. In the monumental People in the Sun (1960), a horizontal canvas of forty by sixty inches, five fully dressed figures seated on folding chairs seem gathered to watch the sunset. A woman in a straw hat has a red scarf around her neck. The man behind her—perhaps a stand-in for Hopper—reads a book. A modernist building of seemingly grand proportions rises behind the sunbathers. As we follow their line of sight, we almost expect to see breakers on a beach. Instead, there’s a row of purplish mountains over an expanse of brown grass. “The idea,” Hopper wrote, “was suggested by seeing people in Washington Square Park getting the sun—the park benches in the fall and winter. I changed the locale to a western setting.” A mashup of Tucson and Lower Manhattan wasn’t particularly challenging, apparently. “To keep the chairs’ legs from being too insistent” was.

The peculiar mood of People in the Sun reminds me of a poem by Robert Frost, Hopper’s favorite poet, called “Neither Out Far Nor In Deep,” about people seated by the ocean:

They cannot look out far.

They cannot look in deep.

But when was that ever a bar

To any watch they keep?

Eager to instill these lines with existential dread, Lionel Trilling called Frost “a terrifying poet.” Randall Jarrell better captured Frost’s deadpan mood. “It would be hard to find anything more unpleasant to say about people than the last stanza,” he wrote, “but Frost doesn’t say it unpleasantly—he says it with flat ease, takes everything with something harder than contempt, more passive than acceptance.” Harder than contempt, more passive than acceptance: that seems to me a pretty good description of Hopper’s best paintings.

This Issue

February 23, 2023

Ukraine in Our Future

Very Free and Indirect

-

1

See Emily C. Burns, “Spectral Figures: Edward Hopper’s Empty Paris,” in Empty Spaces: Perspectives on Emptiness in Modern History, edited by Courtney J. Campbell, Allegra Giovine, and Jennifer Keating (University of London Press, 2019). ↩

-

2

Controversy has surrounded some of the Whitney’s Hopper holdings. See Kevin Flynn, Julia Jacobs, and Robin Pogrebin, “How Did a Minister Come to Own Hundreds of Edward Hoppers?,” The New York Times, October 19, 2022. ↩