One evening in 2015, the writer Michael Frank rushed in late to a lecture at the Casa Italiana, the home of New York University’s Department of Italian Studies in Greenwich Village. As he plopped into the sole remaining seat around a long table, the elegant older woman next to him asked, in a thick Italian accent, “Where are you coming from that you’re in such a hurry?” A French lesson, he replied. She followed with two more questions: “Might I ask why you are studying French?” and then, “Are you interested in knowing how French served me in my life?” (Evidently the Casa Italiana observed a properly Italian sense of timing for starting its lectures.) Frank told her he was studying French to reacquaint himself with a language he’d learned in school but had since buried under layers of Italian. Stella Levi had a more complicated story to tell. Knowing French, she revealed, had not only served her but saved her:

“When I arrived in Auschwitz,” she said, “they didn’t know what to do with us. Jews who don’t speak Yiddish? What kind of Jews are those? Judeo-Spanish-speaking Sephardic Italian Jews from the island of Rhodes, I tried to explain, with no success. They asked us if we spoke German. No. Polish? No. French? ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘French I speak…’”

The program that drew them both to the Casa Italiana that evening was a discussion of museums, memory, and the atrocities committed under what Italians call nazifascismo, that infernal partnership between Benito Mussolini’s puppet Republic of Salò and the German occupation of Italy between 1943 and 1945. Frank, born after World War II, came to the lecture out of interest. Levi, born in 1923 on the island of Rhodes, came as a witness to the Nazis’ last deportation of Jews from Greece. Those deportees from the eastern reaches of the Mediterranean also took the longest road to the death camps deep in the forests of Poland, and for Frank, “When I arrived in Auschwitz” provided an unforgettable prelude to that evening’s event.

The brief conversation impressed Levi as well. At the age of ninety-two, she had decided recently to record her memories of life in Rhodes, and through a mutual friend, also present at the lecture, she eventually asked Frank to give her few pages of recollection a professional’s once-over. Instead he became, in effect, Stella’s scribe. A Hundred Saturdays distills his six years of visits to her New York apartment, as he, an exceptional listener, drew out a wealth of stories from “a woman I would come to think of as a Scheherazade, a witness, a conjurer, a time traveler who would invite me to travel with her.”

In many ways, Stella Levi seems to have furnished the ideal antidote to Frank’s harrowing youth in the company of another older woman, his flamboyant, overbearing aunt Hankie (née Harriet), a Hollywood screenwriter who embodied the Frank family’s nightmare version of Auntie Mame—stylish, imperious, dictatorial, and ultimately unbearable. In his memoir The Mighty Franks (2017), he recreated not only Aunt Hankie’s predatory pursuit of “larky” experience with her favorite nephew (an honor that came at a grueling price), but also the palmy atmosphere of Los Angeles in the era when stars still clung to the last shreds of true cinematic glamour.

That world is as long gone as Levi’s Jewish Rhodes, but both still lie latent in a cloud of living memories—memories of both mind and body. Some twenty years ago, at an exhibition of dresses from the 1930s and 1940s at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, I saw old Hollywood come to life when the elderly women who entered the gallery, all dressed in what they would have called slacks once upon a time, began, unconsciously, instinctively, to move as they once had moved inside their own versions of those expertly tailored dresses, stepping smartly in their comfortable shoes with a slow sway of their hips to make the imaginary fabric of their flared skirts swirl around them. Deep down, they still carried themselves like Marlene Dietrich in Morocco.

Stella Levi’s memories also float and swoop like those gowns. What she bore inside her (and continues to bear: she will turn one hundred on May 5) was not simply the traditions of an old country—really a vibrant mixture of old countries—but also the excitement of her rebellion against those traditions, her embrace of modern life, of dresses with the same swirling skirts the Hollywood ladies remembered, of the stylish cork sandals she wore to Auschwitz and kept wearing until they broke apart. Stella’s panache proclaimed her utter rejection of her grandmothers’ heavy alla turka robes and the embroidered caps that never left their heads.

Advertisement

Inexorably, progress was coming for the Rhodian Jews almost as quickly as the Nazis. Levi’s grandmother Mazaltov Halfon had barely left the Jewish quarter in her entire life; Stella routinely slipped outside the old city walls to go swimming in the sea with the Italian men who shared her athleticism and her sense of adventure. From the age of fourteen she kept a packed suitcase by the door, ready for the moment when she could finally fly away to an Italian university; instead, at twenty-one, she was shipped off to Auschwitz.

Rhodes, the easternmost of the Greek islands, was conquered by Mycenaean Greeks in the Bronze Age, but its position at a strategic point in the Mediterranean forever fostered a unique, cosmopolitan culture. Today the buildings of the principal city, also named Rhodes, still reflect the presence of the Knights Hospitallers of St. John, who set up a new headquarters there in 1310 after their expulsion from Jerusalem. Catholic corsairs from a host of European nations, they stayed for two centuries, until Süleyman the Magnificent ejected them in 1522 and annexed Rhodes to the Ottoman Empire.

Jewish merchants were active in Rhodes from the Hellenistic period, but the community’s composition changed significantly in 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella, Their Most Catholic Majesties of Spain, expelled their entire Jewish population with the help of Grand Inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada. Tens of thousands of Spanish-speaking Sephardim, with their distinctive liturgy, law, and customs, scattered from Antwerp to Alexandria, many of them scholars, doctors, and rabbis—an entire professional class.

Unfortunately for the Jews of Rhodes, the Knights of St. John, with whom they had lived side by side for centuries, decided to adopt Spain’s anti-Semitic policies, and in 1502 Grand Master Cardinal Pierre d’Aubusson decreed that Jewish Rhodians must convert to Christianity or be expelled from the island. The community was decimated. Twenty years later Süleyman seized Rhodes from the knights (who eventually moved to Malta) and settled 150 Jewish families from Salonika inside the city walls of the capital. Ensconced in their own quarter, the Juderia (tellingly, a Spanish word), free from restrictions on the kinds of trades they could pursue, free to worship according to their own Sephardic traditions, the Rhodian Jews, or Rhodeslis, lived and prospered among Orthodox Greeks, Catholics (who returned in the eighteenth century), and Turkish Muslims for nearly four and a half centuries. By the early twentieth century their population had reached almost 4,500.

In 1912 the crumbling Ottoman Empire ceded Rhodes to Italy, and the island’s prevailing—and notably tolerant—Turkish culture began to give way to the twin pressures of modern Europe and Italian Fascism. Stella’s father, Yehuda Levi, “in his clothes…language, and general sensibility, was in many ways essentially Turkish.” He still wore a djellaba at home and a fez to work with his Turkish business partner, at least until his Italian-educated children begged him to put it away. He had married, by arrangement, Miriam Notrica, the daughter of a prominent local banking family. The names of their seven children reveal a plethora of languages and cultural influences: Morris (Moshe), Selma, Felicie, Sara, Victor, Renée, Stella. Stella spoke Judeo-Spanish at home, Italian in school, learned French from her sisters, who had attended the French school in Rhodes, and picked up Turkish and Greek from her friends and neighbors. She learned English in New York when she arrived in the late 1940s.

The culture of Rhodes may have been as vibrantly international as ever around the turn of the twentieth century, but economic conditions became increasingly difficult in the Jewish quarter as the Ottoman Empire tottered and fell after World War I. Young men had already begun to emigrate in the late nineteenth century, to the United States, Buenos Aires, Rhodesia, and the Belgian Congo. Both of Stella’s brothers would eventually leave: Morris for Los Angeles and Victor for the Congo. Yehuda Levi had always made a good, if not lavish, living selling wood and coal and operating the customs scale at the port of Rhodes with a Turkish partner, but he was certainly not prosperous enough to move his family into the new Italian-built houses outside the city walls, where the Notricas and the other wealthy Jewish bankers now chose to live.

As a result, Stella grew up among the close-packed courtyards and perpetually open doors of the old Juderia, surrounded by wafting smells of pastry and pasta, swathed in a dense tapestry of song, embroidery, conversation, ritual, and family. Here Yehuda could cross the street every day to pray in the synagogue and Miriam could make a daily round of visits to family and friends. Free to wander the Juderia, sleeping at her cousins’ house or at home, Stella spent her Rhodian childhood lovingly nurtured and itching to escape. Decades later, her prodigious memory still registered the textures and colors of her early life with uncanny precision, but perhaps she always sensed that those seemingly solid traditions were as fluid as the turquoise Aegean. At some point in their conversations, Frank realizes that Stella never once saw her nuclear family all together at the same time.

Advertisement

Life in the Juderia was literally magical, still haunted by spirits in the first decades of the twentieth century. Every so often the rabbi would spread word through his sexton, the shamash, that an evil force, so fearsome to name that it was evasively called “the sweetness” (la dulce), was about to enter the community’s water supply. Women filled up bottles and bowls with water and covered them, and for several hours, perhaps half a day, no one washed or turned on the tap until the danger had passed. Traditionally, no one ever set the table with knives or bathed at home; instead, once a week, before Shabbat, families went to the hammam. Asthma was cured by inhaling marijuana fumes or drinking it in a tisane. Sliced potatoes applied to the head cured migraine. “Don’t say, ‘My God,’ Michael,” Stella protested one afternoon as she described some of her family’s traditional remedies. “There was a logic to these cures. They had been handed down through the generations. And, what’s more, they worked.”

All the same, she never quite believed in la dulce, nor did she ever avail herself of the enserradura, an extreme treatment her grandmother practiced on emotionally troubled adolescent girls in the neighborhood: for a week, enclosed in a silent room (her family and neighbors would be encouraged to move out of their houses if necessary), the girl rested, eating nothing but a thin broth. Creating an island of peace within the bustling, crowded Juderia might have soothed the anxiety of some Rhodian girls, but Stella disdained the idea; she would rather strike out on her own, with a good book or a swim in the sea.

Mussolini marched on Rome the year before Stella’s birth, and thus the only Italy she knew was Fascist Italy. She regarded Italy, whose language she spoke and to which she felt a profound connection, as glamorous and modern. Until 1936 the colonial grip on Rhodes was relatively benign: the Italians brought running water and electricity to the Juderia; paved roads; opened schools, a theater, and a cinema; and brought in modern medicine. They tore down the old souk and peppered the ancient city with incongruous Fascist-style buildings. They introduced taxis, buses, and motorcars, encouraged sports, drained swamps. The local governor, Mario Lago, even convinced Mussolini to found a rabbinical school.

All that changed in December 1936, when Lago was replaced by Cesare De Vecchi, Count of Val Cismon, Mussolini’s minister of education, who had specifically requested his new appointment as “governor of the Italian Possession of the Aegean Isles” after a visit to Rhodes earlier that year. At first, De Vecchi’s presence only seemed to create a change in the atmosphere; the Juderia’s life a la turka seemed more precarious, less in touch with the times, as the drive toward modernization began to show its ruthless side. But the passage of Mussolini’s anti-Semitic Racial Laws in 1938 fell on the Juderia like the blow of an axe. Yehuda lost his job; Stella and her sisters were banned from school.

A local Italian, Luigi Noferini, set up a clandestine school for Stella and five Jewish boys. She was fifteen, he was almost thirty, but the urgent conditions forged an urgent friendship. And one evening when she was seventeen, “they were sitting alone side by side at his desk. They had finished lessons for the day. Stella closed her book, and Noferini put his hand on hers. Just that, no more.” Through Noferini she met another Italian, Gennaro Tescione, a Neapolitan lawyer in his late twenties stationed in Rhodes as an army lieutenant; if Noferini stimulated her intellect, Tescione struck something in her soul. Stella met a third Italian, the Jewish businessman Renzo Rossi, on the beach one day with a group of her friends from the Juderia, and his villa became a refuge from the dread that suffused the community. Yet she recognized that the Racial Laws also bound her more closely to her Jewish friends and to their remarkable heritage.

By 1939 wealthy, well-connected Rhodian Jews were leaving the island, for Tangier, Congo, Argentina, the United States, but the residents of the Juderia, clinging together, adopted a kind of collective denial. On September 8, 1943, Italy’s Grand Council, which had deposed Mussolini in July, declared an armistice with the Allies, but much of the country, and all of its conquered territory in the Balkans and Greece—including Rhodes—passed directly to Mussolini’s former ally Adolf Hitler. Stella’s Italian friends Renzo Rossi and Luigi Noferini fled the island, Noferini to serve with the partisans in Tuscany, Rossi, as a Jew, simply to survive. Gennaro Tescione, as an officer in the Italian army, shot himself rather than obey a summons to report to Germany. The Levi family’s savings, like those of their Jewish neighbors, began to run out.

On July 23, 1944, the SS rounded up the remaining Rhodian Jews, more than 1,700 of them, and put them on a boat to Piraeus.* During that miserable eight-day journey the ship made a single stop, at the island of Leros, to join another vessel full of Jews collected from the island of Kos and to pick up provisions (for the crew only), along with the single Jew residing on Leros. Twenty-three passengers died en route, mostly the old people crammed into the bilge without sanitary facilities, food, or water. In all, it took three and a half weeks for the Jews of Rhodes to reach Auschwitz-Birkenau: first they spent three days massed in the SS transit camp of Haidari west of Athens, and then endless days packed into cattle cars headed north. Amazingly, Stella and her sister demanded—and received—permission to step out of their car and wash their hair at a pump during a stop at a Czech railway station.

The men who finally opened the doors at Auschwitz station on August 16 were Greek Jews from Salonika. As they unloaded the Rhodians’ suitcases, they quickly whispered in Judeo-Spanish to hand babies over to the old people. They dared not explain that young women holding infants went straight to the gas chambers, but healthy young women had a chance of survival as forced laborers. These fellow Judeo-Spanish Greeks had already survived for months; they were among more than 40,000 people—nineteen trainloads—deported from Salonika to Auschwitz between March and August 1943. By December 1945 fewer than 2,000 Jews lived in Salonika, once a community of 50,000.

Of the 1,700-plus Rhodian Jews who made the journey to the death camp with Stella, 1,200 were gassed immediately, including her parents, and only 151 lived to see the liberation of Auschwitz in late January 1945. Of the fifty people left behind in Rhodes, forty-three found protection from the courageous Turkish consul, Selahattin Ülkümen, who arranged for them to get Turkish citizenship and emigrate to Turkey. (Ülkümen also saved Jews in Kos and is honored at Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.) But all these survivors had emigrated to Turkey by 1945. An ancient woman of ninety who had somehow slipped through the cracks lost her mind and wandered her deserted neighborhood until she died of starvation shortly after the cattle cars with her neighbors reached their destination in Poland. In a little more than a year, then, the Nazis extirpated Jewish life in Greece, destroying communities that had lasted for centuries in the case of Salonika, millennia in the cases of Athens and Rhodes.

Why did the Germans bother to send the Jews of Rhodes all the way to Auschwitz? Stella wondered but never found an answer. Initially, packing people off to the East had been a way to hide the evidence of the Final Solution, but by August 1944, when the Rhodeslis came to Auschwitz, the secret was out: in July the Soviet army had discovered and liberated the Majdanek extermination camp. As Nazi power eroded and then collapsed, Stella was transferred from camp to camp in an increasingly desperate effort to conceal the system from the advancing Allies. Auschwitz fell in January, but Stella, perpetually on the march from Poland to Bavaria, found freedom only on April 6, 1945. Rather than returning to Rhodes, where the properties of the Juderia had all been confiscated and its social fabric destroyed, she asked to be sent to Italy. In Florence, she was reunited with her former clandestine teacher, Luigi Noferini, and no doubt broke his heart when she moved on to New York, Los Angeles, and back to New York again.

To the last of the one hundred Saturdays we spend with her, Stella keeps the Holocaust in a separate mental compartment, a Pandora’s box she knows better than to open all the way. The trauma she allows herself to feel fully is, instead, the humiliation of the Italian Racial Laws, which sapped her self-confidence as a teenager and encapsulated the greater horror to come. The experience of the camps she relegates to another Stella: the conniving, thieving survivor who bartered potatoes and pieces of bread with male inmates through a hole in the wall that separated the men’s latrines from the women’s, and who stepped out of the cattle car to Auschwitz to wash her hair at a water pump along the way.

What ultimately pushed that Stella toward life, however, was the stubborn physical effort of her sister Renée, who shoved her forward, shivering with fever, for three days as they marched from a nameless satellite camp of Dachau to another camp at Allach, and thence to liberation. Had she stayed behind in the infirmary, she would have been taken to Dachau and gassed. In the end, every survivor, Stella insists, depends on nothing but luck.

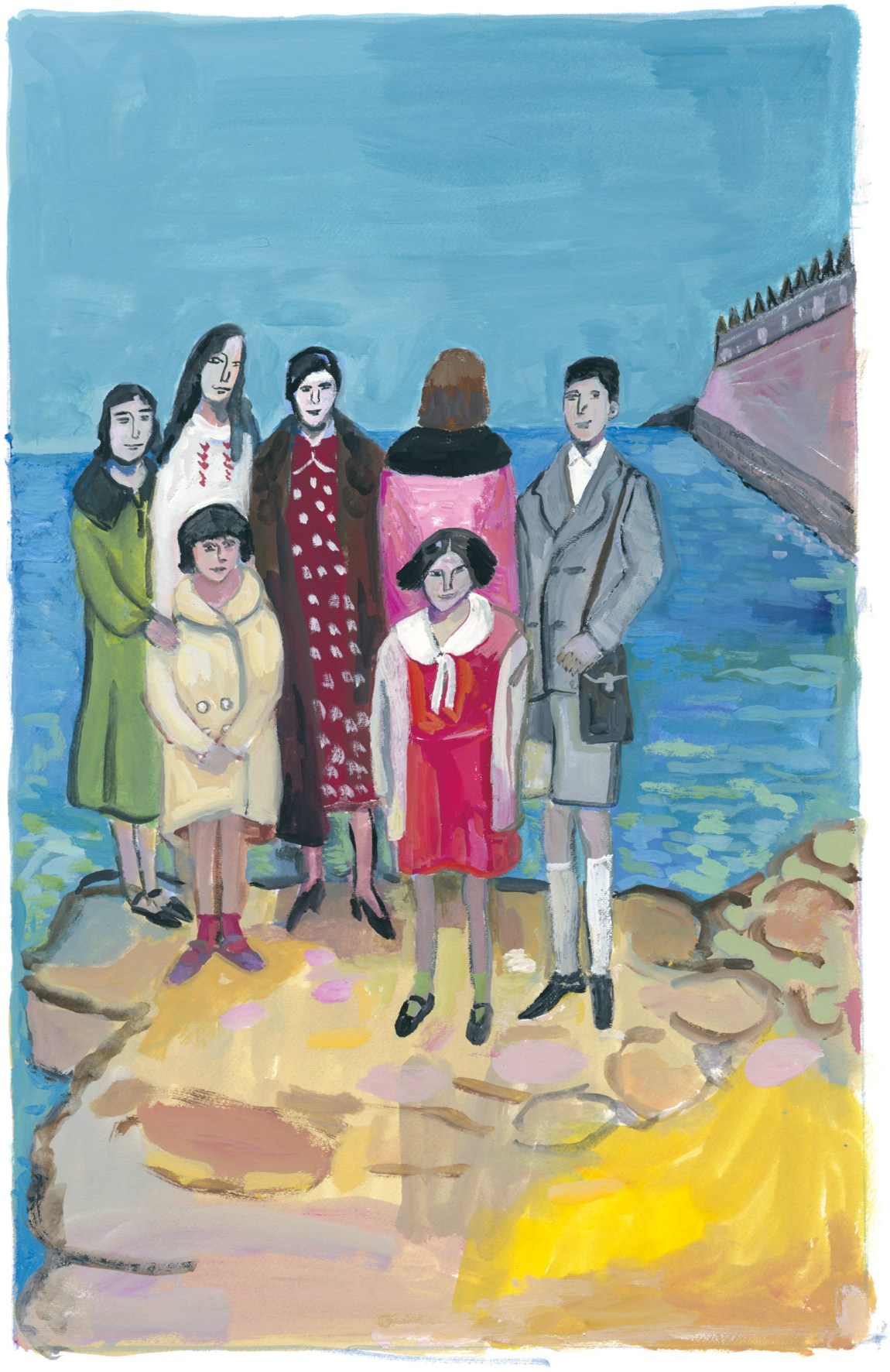

It seems fitting that One Hundred Saturdays should be an illustrated book, for Stella Levi’s tales are profoundly rooted in sensory experience—of spaces urban and domestic, open and closed, of salt water, honey-soaked pastries, silk nightgowns, huddles of children, snatches of melody and rousing choruses, the erotic thrill of skin on skin. Maira Kalman’s paintings—based on surviving photographs of the Levi family, Stella, Noferini, and Tescione—infuse those black-and-white images with Mediterranean color to create a singularly attractive book, a tribute not only to an exceptional time and place, but also to the exceptional person charged with the task of commemorating it, a witness whose independence, integrity, and zest for life would have been irresistible at any time, in any place.

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Becoming Enid Coleslaw

Putin’s Folly

Descriptions of a Struggle

-

*

Frank gives the dates as Levi remembers them. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum reports the date of the deportation as July 20, 1944. The number of deportees varies in different accounts, but Frank, in a personal communication, suggests a figure of over 1,700. ↩