1.

The comic book really is a perfect consumer item. It’s portable, flexible, cheap enough to be disposable, durable enough to last several lifetimes with proper archival care, lightweight, colorful and simple (no packaging or shrink-wrap required). Think in terms of the entire package, the structural cohesion of every component (from page numbers to indicia, etc.)

—“To the Young Cartoonist,” Modern Cartoonist (1997)

In 1989 a two-dollar comic book called Eightball debuted with the aggressive subtitle “An Orgy of Spite, Vengeance, Hopelessness, Despair and Sexual Perversion.” True to the letter, the five vices suffuse its thirty-two black-and-white pages. In the surreal opener, “Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron,” our hero gets blindsided by a creepy bondage movie, soul-kissed by a filthy drunk, and arrested by sadistic cops; he periodically flashes back to the troubled face of some lost love or phantom. Then there is “Devil Doll?,” a takeoff on those tracts drawn by the evangelical cartoonist Jack Chick that proselytizers still leave on subway seats—a campy-cruel three-pager in which heavy metal, PCP, and D&D lure a woman to a life of sin. (After getting a pentagram tattooed on her brow, she cackles, “I think it looks #@* radical!”)

Next comes a sleazy fable of adultery and novelty gags (“The Laffin’ Spittin’ Man”), dressed to kill in angular midcentury fashions and punctuated with the airborne sweat droplets known in the comics trade as plewds. The closing feature is “Young Dan Pussey,” a warts-and-all take on a superhero comics mill—a meta-maneuver suggesting firsthand experience. “Get a move on, boys! Breakfast is ready!” cries the taskmaster to his underpaid team, bunked in the Infinity Comics compound. “Pages are waiting to be pencilled, written and inked!”

Varying in tone and ambition, each of the comics in Eightball’s first issue fixates on verbal zing and graphic textures. Faces tend to be grotesque, and the dialogue is often stylishly rancid (“Yeah, stop fucking around, Douche…I don’t want our sales to be affected by this unreadable shit!”), but the comics’ sheer beauty and mystery can also knock you out. The opening panel of the first story is a close-up of a stunning, raven-haired woman, with earrings that (on the third or thirteenth read) turn out to be Thalia and Melpomene, the classical masks of comedy and tragedy. Her face is so hypnotic, you miss what’s hiding in plain sight.

Eightball was published not long after Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking memoir Maus (1986) and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s caped-crusader deconstruction Watchmen (1987), when the mainstream American press briefly lauded the literary potential of comics, but its word-drunk selection has little in common with such monumental works. It felt like the future, arrived at through the past. The shading effects were done cleanly in Zip-A-Tone (a soon-to-be-discontinued adhesive sheet), and the peculiar lettering could look plucked from an earlier era, its fussiness forcing readers to come closer, slow down. At two bucks, the comic was a bargain, dense and delirious. Maybe too dense. In one story, the hard-boiled narrator breaks the fourth wall to grumble about space limits as he contemplates his dire straits: “A good question that deserves an answer—unfortunately I only have 6 pages in this issue so you’re gonna have to take my word for it.”

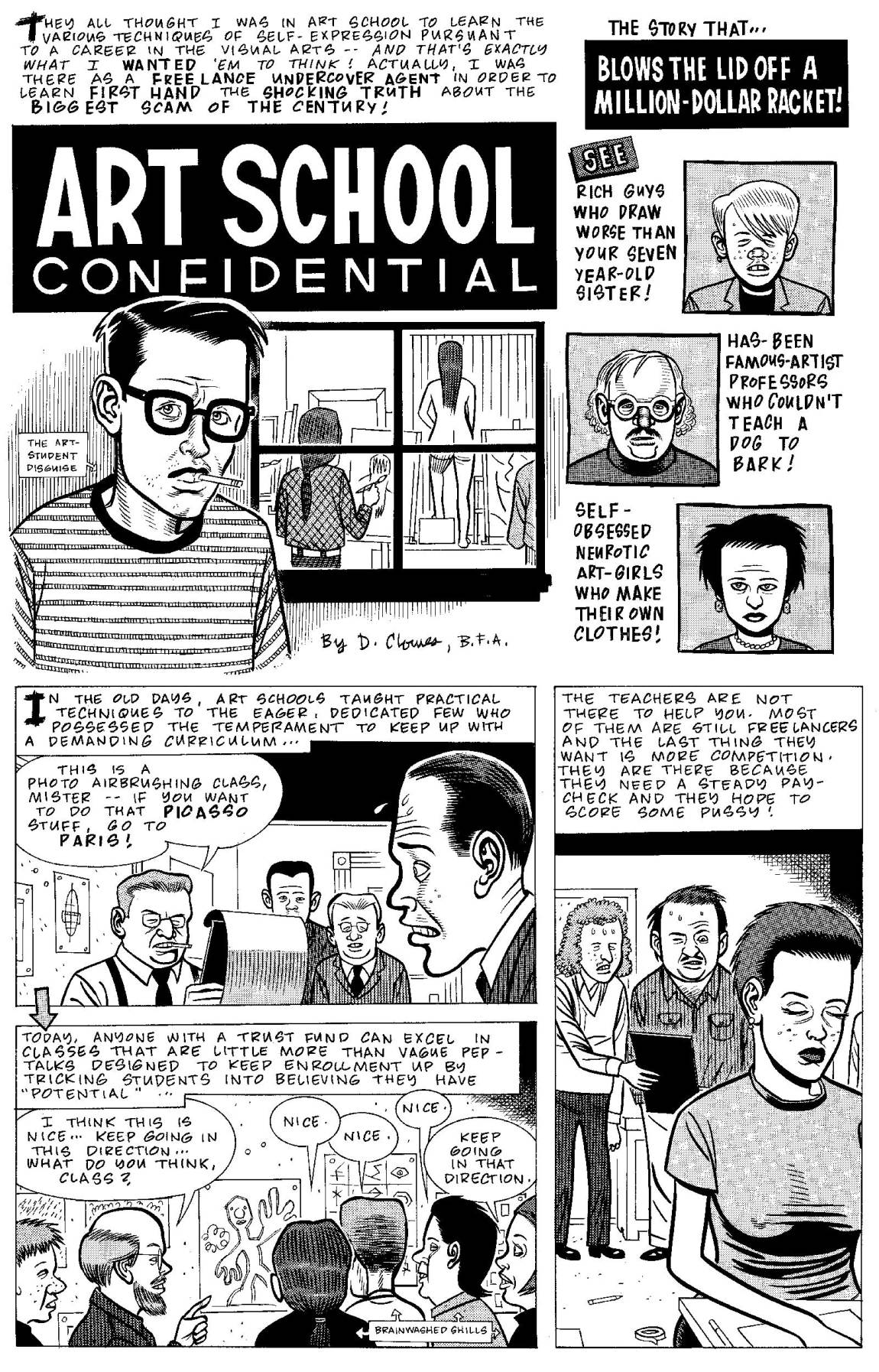

The joke is that he has no one to blame but himself. Everything in Eightball was done by the artist Daniel Clowes. He was twenty-eight and living in his native Chicago, after a stint in New York, where he studied at the Pratt Institute—later lampooned in “Art School Confidential”—and drew comics for Cracked. (Unlike misfit penciller Dan Pussey, he never served time at a superhero outfit.) For the inaugural issue, he signed his pieces Daniel Clowes, D. G. C., and Dan Clowes. Future issues ran bylines from Dan’l Clowes, D. Gillespie Clowes, “Tubby” Clowes, Young Dan Clowes, and more: an industrious crew of misanthropic ink studs and true artistes, all easily summoned with a glance in the mirror. (“I’ve always felt that I had all these different, very unrelated parts of my personality, and I wanted to be able to do stories with each of these different parts of my personality in the same book,” he later said.) Covers and an occasional feature were printed in color, for him an almost masochistic feat involving Mylar film, blue-lining, and the cutting of transparent Pantone sheets. By issue 10, Clowes had divorced, remarried, and relocated to Berkeley. The cover price was fifty cents more.

Other adventurous comics found their way to store racks in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and you could detect in Eightball a tinge of the nightmare logic of Chester Brown’s Yummy Fur, the pop-culture mockery of Bob Burden’s Flaming Carrot, the precise body horror of Charles Burns’s Hard-Boiled Defective Stories, and the midwestern rue suffusing Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor. (Lloyd Llewellyn, swinging star of “The Laffin’ Spittin’ Man,” first appeared in a teaser included in an issue of the Hernandez brothers’ Love and Rockets.) But in the spirit of that titular sphere, Eightball defied categories, ricocheting like mad from the start. Or is it that, when shaken, it foretold some of the comic medium’s possible futures?

Advertisement

From 1989 to 1997, Fantagraphics published the first eighteen issues, which have now been collected in one bullet-stopping volume as The Complete Eightball.1 The tentpoles are two serials that proved Clowes could do pretty much anything: the labyrinthine, Lynchian Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron and—beginning immediately after—the indelible female friendship saga Ghost World, both of which have been issued as separate volumes (and, in the latter case, developed into a much-loved film). But it’s a richer experience to read them in situ, interrupted by everything else. Clowes was driven to perfectionism, as well as to fill pages—deadline as mother of invention.2

Thus we find unhinged screeds (a Clowesian proxy lists personae non gratae in “I Hate You Deeply,” including “People who don’t capitalize their name,” while “The Future” forecasts that “everybody who ever recorded anything will at some point be called a genius by somebody”—see today’s oversaturated podcast market for proof), instantly fizzling franchises (“Hippypants and Peace Bear”), and wry urban daydreams (“Marooned on a Desert Island with the People on the Subway”). There are slightly facile musings on art-making (“Grist for the Mill”), as well as emotionally plangent stories that say more in a dozen pages than most graphic novels can at ten times the length. Of this last group, “Immortal, Invisible,” “Like a Weed, Joe,” and “Blue Italian Shit” are luminous memory plays that, despite centering on different characters, read like episodes in a single sentimental education.

Impressive later works like “Caricature” and “Gynecology” distill the earlier misanthropy into compulsively readable noir-tinged narratives. They have the meandering magic of a Cheever story like “The Country Husband” or “The Day the Pig Fell into the Well”: populated with curious characters who enter and exit without fanfare, told in a voice bursting with regret yet also ecstatic with the sheer talent expended in the telling.

The busy, fevered covers—everyone looks deranged—practically shout for a browser’s attention, in contrast to the subtler ones gracing later Clowes books like Wilson (2010) and Patience (2016). Even the letters sections (“The Bulging Mailsack”), prank-call contests, and ads for mugs and T-shirts feel crucial, providing a glimpse of the hustle and flow of audience engagement in the pre-Internet era.3 The Complete Eightball comes with no overarching table of contents for its five-hundred-plus pages, making individual pieces hard to hunt down. (I developed an elaborate system using shredded Post-its.) The absence compels you to read the whole thing in sequence, to regard it as a polyphonic magnum opus tilting at the monoculture, born under Bush I and stretching into Clinton’s second term. It’s a madcap portrait of the artist as generational talent, recycling and refining his themes, as well as a time capsule bearing the moods and mores of an American decade now so distant it might as well be the age of Atlantis.

2.

[Comics] are in a sense the ultimate domain of the artist who seeks to wield absolute control over his imagery. Novels are the work of one individual but they require visual collaboration on the part of the reader. Film is by its nature a collaborative endeavor…. Comics offer the creator a chance to control the specifics of his own world in both abstract and literal terms.

—“So, Why Comics?,” Modern Cartoonist

“To me, my art looks perfect when I do it,” Clowes told The Comics Journal in the summer of 1992.

I mean, it’s really what I see in my head. To me it looks almost like a diagram or like a coloring book or something. It really looks very…I don’t want to say bland, but it just looks very perfect. It looks exactly the way the world should look. And I don’t see a style at all. I see it as being each face is the way a face really looks…. People tell me they can recognize my style, and I don’t understand what they’re talking about. I don’t see my style.

The interview was published shortly after Eightball #9, containing the penultimate chapter of Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron; the serial would reach its shattering finish two months later. Clowes’s confession-cum-manifesto, as he nears the end of his landmark work, is a mix of modesty and bravado, the tone half-kingly, half-savantish. His facility with multiple modes might suggest the absence of a singular style (in the same interview, he prioritizes doing “all different kinds of drawing”), but even in their variety, his panels are always recognizably Clowesian—and miles away from bland.

Advertisement

Glove is a startlingly original comic that nevertheless trails numerous influences, from the title (nicked from Russ Meyer’s ferociously great 1965 film Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!) on down: a Manson-like cult, Lovecraftian fish-folk, a ubiquitous logo that recalls the post horn in The Crying of Lot 49, not to mention an important locale (Hourglass Lake) that also figures in Lolita.

As in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), a young man descends into a twilight zone behind an explicitly all-American façade.4 A bric-a-brac connoisseur, Clowes conjures a shadow world of grim diners and collectible tchotchkes, moronic ad copy (“Hey! I Need a Liquor Store”) and periodicals like The Octagon (newspaper) and Luv Canal (girlie mag, named after the infamous toxic dump site). Cryptic storefronts do slow business at odd addresses: you can find Yahweh’s Mistake at 1977 Hair Street. Call it gentle magic realism, a playful twist on the everyday that prepares the reader for more profound breaches of reality.

Clay Loudermilk is less of an innocent than Jeffrey Beaumont, Kyle MacLachlan’s Blue Velvet character; the story starts with him visiting a porn theater, after all, and we piece together that he’s divorced. What he sees onscreen is not what he came for: a bizarre S&M movie, entitled Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, with a mustached man in diapers and a dominatrix who looks alarmingly like his ex-wife. (We don’t grasp this till later; we don’t even learn Clay’s last name till episode 3.) The masks of Melpomene and Thalia pop up on the end credits, bracketing the list of pseudonymous actors (Abel Caine, Brock Thunder, Madam Van Damme) and the name of the auteur: Dr. Wilde. According to a restroom sage, who dispenses advice—legal, dermatological, and otherwise—from atop a toilet seat, the company responsible for that unsettling film, Interesting Productions, is located in Blackjack County. Which is where things really get weird.

Able-bodied, with a healthy head of hair, Clay is nonetheless so staggered by this celluloid version of his ex—is it really her?—that for the rest of the saga, he’s depicted with bags under his eyes, desperate for a solid night’s sleep. Some scenes, seen once, can’t be unseen. This goes for the reader, too. For all its visual wit and honed banter, Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron unfolds as a series of dangerous visions, designed to make us reel. It’s apt that Glove’s first chapter delivers not just forbidden sights, but monstrous means of seeing. One of Clay’s friends, ludicrously, appears with the tails of “Asiatic sea crustaceans” flailing from his sockets, to treat some ocular malady; he explains that his doctor had his eyeballs removed, and the creatures were “there to eat out the bacteria.” Later Clay sits handcuffed in the back of a police cruiser when the cops stop a mute, possibly somnambulant woman who has three vertical eye slits in her face. One figure sees nothing; the other, too much.

The overall effect is startling. It looks exactly the way the world should look. At its most potent, Glove can feel like it alters, even negates, seeing. During these moments of high anxiety and maximal weirdness, style is obliterated or irrelevant. The images attack too quickly for style to be processed, like medicinal sea worms that dive straight through the eyeholes and into the brain.

Like Clay, we want to see more, even if it ruins us. His dark desire for the truth—the imperative to cherchez la femme—brings him into the fold of conspiracy theorists, who see in a grocery chain’s primitive logo the sigil of some vast secret network, and into a death cult prepping for the Great Cleansing, an apocalyptic revolution that involves the assassination of the advice columnist Ann Landers.5 Clay strays into the clutches of a seductress or three as he hunts for clues. All the while, he shows decency to those he encounters, no matter how strange they look: a lovelorn waitress who is part fish, a genetically engineered pet with no orifices, a crawling man who helps him out with directions. As in Faster, Pussycat!, violence erupts on a hair trigger; but unlike the exhilarating drubbings doled out by the Amazonian Varla (Tura Satana), the ones delivered by a testosterone-injecting brute named Geat kill the soul.

Clay lodges across the street from his quarry: Interesting Productions, the secretive entity behind the tawdry film. Through binoculars, he spies a small, pipe-smoking girl at a desk, perpetually writing. (Going through her trash, he later discovers she’s simply drawing the same picture of a horse head, over and over.) When he gets inside, his fate is sealed.

Once he enters the building, movie titles are tacked to a corkboard, with keys to corresponding screening rooms. Clay takes three keys. The first film is a bug-eyed rant (delivered, in fact, by Dr. Wilde, the director); the second, a perverse silent movie in which two babies are made up to look like bride and groom. He walks out of both. With grim fairy-tale logic, the third selection is the worst thing he could ever see. Later, in one of the most devastating reveals in comics, it turns out that—spoiler alert—all of Interesting Productions’ plots, from insipid to sadistic to literally murderous, come directly from the pipe-chomping girl’s mind, as transcribed by a slavering Dr. Wilde. By the end, Clay is molded into a new shape, his fate in line with his name.

3.

Think of the comic panel (or page or story) as a living mechanism with, for example, the text representing the brain (the internal; ideas, religion) and the pictures representing the body (the external: biology, etc.), brought to life by the almost tangible spark created by the perfect juxtaposition of panels in sequence.

—“To the Young Cartoonist,” Modern Cartoonist

The snippets of letters that ran in Eightball #11, responding to the end of Glove’s run, read as though written in a state of shock. “Exactly what was that all about??” wonders one reader, while another says it “left me with the same feeling I got when I finished 100 Years of Solitude—life can be so great, and yet fucked.” Clowes later joked that #11 was “one of the most incoherent issues,” and some of it feels pro forma, as if he were depleted after the labors of Glove. There’s the interior monologue of someone bored at a party; an Irish folktale “illustrated by D. Gillespie Clowes”; “Why I Hate Christians” (about what you’d expect); and “The Happy Fisherman,” who is nude from the waist down, his privates cloaked by an open-mouthed fish. Actual Hollywood interest in Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron inspired a satiric riff, “Velvet Glove,” but it’s a dud, alternating scenes of a superhero-inflected revamp of Glove with ones of Clowes getting pressured to, e.g., cast Jim Belushi as Geat.

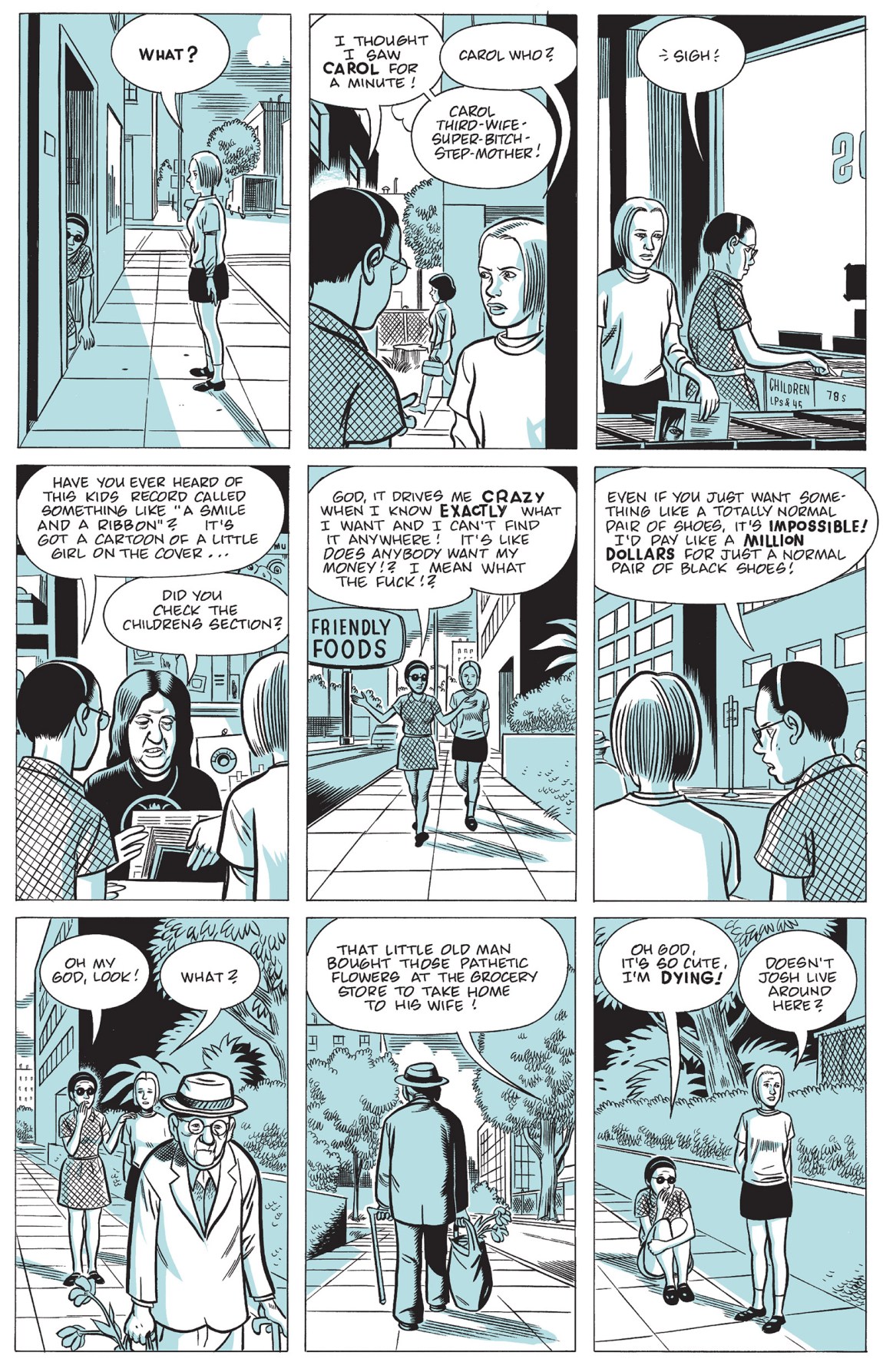

But then, on page 25, there is “Ghost World.” The story stands out immediately, its pages shaded in a delicate blue to evoke the soft glow a TV casts into a room at night, numbing but also holy. Best friends Enid Coleslaw (dark bob, glasses) and Becky Doppelmeyer (blond) are recent high school graduates trying to figure out their next move, and the pleasure is in their fresh faces and how they find diversion—even fascination—living in nowheresville.6 Enid and Becky are witheringly critical of bad music, retro diners, and raw ambition. I was going to call them sassy, but on the story’s first page, Enid rips into Sassy, the magazine du jour for their demographic: “These stupid girls think they’re so hip, but they’re just a bunch of trendy stuck-up prep-school bitches who think they’re ‘cutting edge’ because they know who ‘Sonic Youth’ is!” To which Becky replies, “You’re a stuck-up prep-school bitch!”

Clowes initially didn’t think “Ghost World” would be more than a one-shot, but the voices must have been irresistible. (He cites the charming if casually racist 1964 movie The World of Henry Orient, which follows two teenage girls in Manhattan who are obsessed with a concert pianist, as an influence on his duo’s insular dynamic.) By their second appearance, it’s clear that Enid and Becky are trying to navigate the uneasy life stage between school and whatever lies beyond—and the newly forming obstacles between them—by directing their insecurities outward, mocking their peers and especially the adults around them.

They roll their eyes at do-gooder parents and long-haired waiters, Satanists and psychics and stand-up comics, “guitar-plunkin’ morons” and the “pathetic fucking loser[s]” who resort to personal ads. (“I remember when I first started reading these, I thought ‘DWF’ stood for ‘dwarf,’” Enid says. “I could never figure out why so many dwarves were placing ads.”) Enid sneers that Becky’s foppish former beau seems to have taken fashion cues from “a gay tennis player from the Twenties.” Browsing a free alt weekly sporting the headline “In Bed with the GOP: A Lobbyist Comes Clean,” Enid moans: “People who are super-serious about politics all the time give me the total creeps! It’s like my dad…. I mean who the fuck cares?!”

In earlier Eightball stories, when an embittered Clowes stand-in goes on a tear, you can feel like the hair’s been singed off your head, even if his bile matches your own. (“I wanted to be kinda mean ’cause I’m really sick of these people dominating my life,” Clowes once said.) By having the caustic observations come from two young women whose lives are in flux, and forcing these opinions to rub up against social reality, the story achieves a devastating poignancy while still displaying Clowes’s gift for spite. Unfolding in eight parts, Ghost World is the spiritual opposite of Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron. Though haunted by his past, Clay Loudermilk remains something of a cipher; living in the present, in a world more closely conforming to our own, Enid and Becky are both more normal and deeply rooted.

The title came from some graffiti Clowes passed daily near his home in Chicago; after he moved to California, the phrase floated to mind as he began writing the story, and it memorably captures that sense of being out of step with what’s around you. It’s as though, having plunged his talent deep into Glove’s heart of darkness, Clowes immediately turned it in the opposite direction. A subtle but important mirroring takes place between the S&M mask in the first chapter of Glove, which unzips to reveal Clay’s ex-wife, and the black headgear that Enid buys at Adam’s II, an adult store that she begs her friend Josh to take her to. That mask, divorced from its intended use, looks like part of a superhero costume: the sordid has become adorable. Google “Ghost World,” and one of the first images you’ll see is Thora Birch as Enid in the 2001 film version, winsome in a bat-eared mask.

Edward Gorey devised suitably Victorian-sounding pseudonyms for his morbidly wry stories from the letters of his own name (Ogdred Weary, Regera Dowdy, et al.). Vladimir Nabokov inserted Vivian Darkbloom into some of his books for an enigmatic, anagrammatic cameo. For Ghost World, Daniel Clowes, a serial employer of pen names, rearranged himself, lending his most enduring and endearing heroine his letters. By the end of the book, Enid Coleslaw’s destiny is unclear, but she’s equipped with all the wisdom and love her creator has to offer.7

4.

As we enter, voiceless and impotent, a digital age of “instant access” (or constant excess), the fragile chemistry of this, our hand-held, non-automatic pictorial narrative device and its inherently sublime nuances…appears to be in grave danger. Reading a comic book as God intended is a simple pleasure and as such, our precious pictorial pamphlet, like vaudeville and the magic lantern, is just the sort of thing that gets crushed in the gears of progress.

—“The Future and Beyond,” Modern Cartoonist

In May 2001, two months before Terry Zwigoff’s film Ghost World hit theaters, The Comics Journal ran a long interview with Clowes, whom it had similarly featured in 1992. This time, he got to do the cover. Rather than a single illustration of the kind he’s done on occasion since for The New Yorker, Clowes turned it into a mini graphic memoir. In panel 1, he’s invited to be the subject of an interview. (“Why did I agree to that?” he wonders in panel 3. “I hate The Comics Journal.”) Later, Clowes reads the results with dismay; yet by the last panel, he’s somehow agreed to do the cover illustration. “What’s wrong with me?” he says at his drawing board, composing the comic we’ve just read.

In the interview, Clowes recalls the arduous process of using Rubylith sheets to get the distinctive color effects for Ghost World. It was a bespoke technique he learned at Pratt, and so comically cumbersome that he muses, “I might as well have spent four years learning how to fix a cotton gin.” The grumbling in both cases is tongue in cheek, because the labors he undertook worked. The Comics Journal cover—a Möbius comic strip—is a witty master class in the art form’s seductive charm and narrative flexibility, and Ghost World is what Clowes will be remembered for.

Stuck in the pages of the final issue in The Complete Eightball is a stapled, fourteen-page pamphlet called Modern Cartoonist. Easily detachable, it’s a literal book within a book, with publication attributed to a fictitious Catholic group devoted to the comic art form. On the cover, an eyeshaded artist draws a goofy face on the page before him, while outside the window, a mushroom cloud looms beyond a ruined cityscape. In a tidy, minuscule hand, Clowes—the anonymous author of the pamphlet—first assesses the current (1997) situation, deeming that there are at best “20–25 [comic] creators producing work of an extraordinarily high value,” followed by “25 or 30 with noble aspirations,” and around 2,950 others who are beneath contempt—“teenage millionaires who draw to create fodder for ‘development deals’ and those in waiting to be same.” He praises the power of the form (“Comics have an inherent energy to them…a near-electric charge”), and inveighs against sloppy work, skewering artists who opt for a more “iconic” style (mocked as “The Adventures of a Featureless Blob”). Just as the cultural change wrought by the Internet becomes easier to see, he makes a stand against the “democratization” promised by new technology, looking down his nose at the “structural shift…in the reader’s favor, giving him an exaggerated role in the give-and-take between artist and audience.”

It’s fitting that The Complete Eightball, which contained a parody of Jack Chick’s fire-and-brimstone pamphlets in issue #1, should end with a tract by Clowes himself in the final number. Clowes has reminisced about buying and consuming, in one evening, about sixty of Chick’s tracts, telling The Guardian it was “maybe the most devastating comics-reading experience I’ve ever had.” “I’d never been absolutely convinced by a comic book before in my life,” he told The Imp, Daniel Raeburn’s sporadic but important comics-crit magazine, in 1997,

but I was sure that he was right and that I’d been crazy all along…. To read that many in a row, this overwhelming tidal wave of Christianity coming at you—it’s an amazing experience. Here was this comic dealing with life and death. The absolute most important thing. I mean, he was pulling out all the stops, there was no soft-pedaling, he was just ramming it down your throat. Never before had I been affected like that by comics.

I find Chick’s work repulsive. But it’s easy to see why Clowes found those cheap tracts (eight cents a pop at a Christian bookstore) so potent. Here was someone who used the medium to its utmost, harnessing the power of words and pictures, to his own furious ends. (Chick died in 2016.) Clowes’s religion is comics itself, and every word in Modern Cartoonist—and each panel in The Complete Eightball—is a testament to his godlike prowess. As he told The Comics Journal in 1992: “I was trying to almost create something for myself that I wish existed, or to create for the world something I wish existed.”

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Putin’s Folly

Descriptions of a Struggle

-

1

Five more issues appeared from 1998 to 2004. These later numbers concentrated on single, long-form narratives (David Boring, Ice Haven, and The Death Ray, all later published as graphic novels) and are not included in this volume. ↩

-

2

The Complete Eightball includes a dozen pages of illuminating notes and source images. Of Eightball #6 (June 1991), Clowes recalls that the printing was so abysmal that he “threw the entire box of comp copies out the window onto Division Street about two minutes after cutting it open. Later, after being told by the printer (now out of business: HA!) that we couldn’t reprint until these copies were sold, I went out in the middle of the night and salvaged a few of the copies that hadn’t yet been pissed on by hoboes.” ↩

-

3

Correspondents include fellow cartoonists like Peter Bagge, whose Hate had its heyday in the 1990s, comedian Margaret Cho, a member of Yo La Tengo, Spike Lee’s brother, and a Seattle woman who, after inquiring about the pronunciation of Clowes’s surname, adds, “Did I mention that you are a white male and I hate you?” ↩

-

4

It should be said that Clowes’s Eightball characters are almost entirely white, and the gaze (with the significant exception of Ghost World) is unabashedly male—not unusual for the time, but more glaring thirty years on. Clowes is aware of the uncomfortable embrace of nostalgia. In the provocatively titled “Gynecology,” late in The Complete Eightball, the artist Epps feebly excuses his bias for the iconography of yesteryear, including problematic images, by saying, “I just like the innocence of those old drawings.” And the fried-chicken franchise Cook’s in the 2001 film Ghost World (for which Clowes cowrote the screenplay) is revealed to have originally had a racist name, later fixed by changing one letter. ↩

-

5

In one of Glove’s rare off-key asides, the revolutionaries take over the White House, where they get annoyed by a freshly divorced, foulmouthed Bill Clinton. Clowes drew the panels in July 1992, months before the election, and almost chose to depict Ross Perot in the Oval Office instead. ↩

-

6

The suburban milieu is geographically vague—“a combination of Chicago and Los Angeles…with decaying Midwestern brick buildings and palm trees in the background,” per Clowes. Aimee Mann’s song “Ghost World” (2000), inspired by the comic but released before the movie, suggests the South: “If I don’t find a job/It’s down to Dad and Myrtle Beach.” ↩

-

7

The affection is mutual, to a point. In chapter 3, Becky teases Enid: “Name one guy who lives up to your standards.” “Somebody like David Clowes,” Enid says dreamily. “He’s like this famous cartoonist.” To which Becky replies: “Yick! I hate cartoons!” (Later Enid sees Clowes at a signing and recoils in disgust.) ↩