What counts as eccentric in the garden, and what counts as a folly? As a child I used to be taken on Sunday walks to the Needle’s Eye in Wentworth, South Yorkshire, a kind of sharp pyramid of stone some forty-five feet tall and pierced by an arched passage. It was erected in the early eighteenth century by the Second Marquess of Rockingham, who wanted to make good on a bet that he could drive a coach-and-four through the eye of a needle. If he could do that, the implication was, it shouldn’t be hard for him, a rich man, to enter the kingdom of heaven—whatever Jesus says in Matthew.

That is a folly in one sense of the word—a highly extravagant, eccentric architectural gesture of no practical purpose. The second meaning of the French word folie overlaps with the English term. It refers to a kind of house—une petite maison (though they were not in fact very small) built typically during the Régence (1715–1723) in what were then the suburbs of Paris for the mistresses of very wealthy men. They were called folies after the foliage that supposedly grew up around them to protect the identities of their owners. Of course, by the time the foliage had grown enough to conceal them, little mystery might remain as to the identity of the owner, the lover, the eccentric night visitor.

In their afterlife these follies and their creators may appear in their most eccentric light. They are the ruins of ruins, like the unique house built in the form of a section of a massive broken pillar in the Désert de Retz, François Racine de Monville’s garden at Chambourcy, or the Ruined Bridge at Kew, over which real cows would pass. History was often unkind to these follies. Invading armies were billeted in them. They were neglected or considered ridiculous. But where, by some stroke of fortune, they have survived, or where for instance some part of a typical group of follies has clung on, as in the great landscape garden at Stowe (a stately home that became a boys’ boarding school), then they cease to seem eccentric. They seem important instead, and we lose the bad habit of laughing up our sleeves at them.

Kew Gardens is a grand example of an English landscape garden surviving by passing itself off as a scientific institution. Some of its follies and eccentricities have been tidied away. Sir William Chambers’s Pagoda and the Ruined Bridge remain, together with a real royal residence (Kew Palace). But how many visitors are aware that there was once, in the same garden, a House of Confucius, a Mosque, and an Alhambra, together with a Gothic Cathedral (in wood) and various temples (in stucco)—the whole amounting to an essay on international architectural styles? Eccentric does not begin to cover Kew at its inception in 1759. It was, as has been said, like a world’s fair.

The kind of enterprise we mean by an English Garden—whether it is fitted into a somewhat tight irregular space, like Kew, or allowed, like Stowe, to command the local landscape—differs from its historical predecessor, the Dutch garden, in avoiding straight lines and geometrical figures. It rejoices in winding paths, contrasts of sun and shade, varieties of mood (very much like New York’s Central Park, with its lawns and lakes, crags and kiosks). Ideally it was supposed to lead you through a gamut of emotions, inducing pleasures of a rustic kind, in contrast to, some steps further on, awe at the mighty forces of nature: that is, from the picturesque to the sublime. To this end, it might include poetic inscriptions, monuments (Rousseau’s island tomb in its glade of poplars), a dairy (for a refreshing dish of cream), an aviary (to guarantee birdsong), a grotto with a real hermit, and perhaps a menagerie (once again like Central Park). The English garden at Wörlitz in Saxony-Anhalt features its own Vesuvius, which can still be made to erupt, and next to Vesuvius its own Villa Hamilton, in honor of Sir William Hamilton, the vulcanologist husband of Lady Emma, Admiral Nelson’s mistress. It also welcomed, in its enlightened way, the inclusion of a prominent synagogue. Wörlitz is the epitome of a princely education, a vast souvenir of a Grand Tour.

In the centuries before mechanical diggers, it was a costly—because labor-intensive—business to remove all traces of a Dutch garden when it had gone out of fashion. One simply, where possible, superimposed the English plan on its Dutch predecessor. It sometimes happens that, in times of drought, the ghostly outlines of a “Dutch” garden become visible in the shallows of an “English” lake. This has been observed at Blenheim Palace in Oxford and at St. James’s Park in London, but it could happen all over Europe, wherever the English style once prevailed over the Dutch. The plants and the beloved box hedges have long since been dug up, but the gravel paths remain discernible, with some of their old edgings perhaps. I knew a garden of uncertain age whose paths were lined with an astounding collection of empty stoneware gin bottles. A different sort of Dutch garden indeed. Someone had been hitting the Bols.

Advertisement

Variety was at a premium in the English garden: architectural variety, imitating Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, and variety of landscape. Eccentricity and variety went hand in hand. The follies might serve as markers for a journey from vista to vista, and there might be guidebooks and maps for the convenience of the visitors. Nor is it surprising to find that the intellectual and political interests of the age are reflected in the choice of contents of the garden—botany, as you would expect, but also geology and archaeology.

For Alexander Pope, devising his celebrated grotto at Twickenham, it was not enough to line a cavern with the most valuable stones. The materials had to be geologically correct (What was the proper stone for the floor of a cave? And what for the ceiling?) and they had to be beautiful. They didn’t have to be rare—“glittering tho’ not curious” was the way Pope put it, “as equally proper in such an Imitation of Nature.” This imitation of “Nature” extended to such considerations as the striations of the rocks used and to the architecture of the grotto, which was not regular but was supposed, with its pillars and groins, to resemble supporters left in a quarry—that is, rough-hewn and irregular pillars carved from the living rock.

Clearly a lot of thought went into this grotto, which was something far more substantial than the average Renaissance or mannerist shell-decorated cave, meaninglessly dedicated to some goddess or nymph. Pope was serious. He adorned his cave with an inscription in honor of the Reverend William Borlase, the geologist who had advised him. The aesthetic of the project was quasi-scientific, as noted in a contemporary description:

We are presented with many Openings and Cells, which owe their Forms to a Diversity of Pillars and Jambs, ranged after no set Order or Rule [that is, not Ionic or Corinthian], but aptly favouring the particular Designs of the Place: They seem as roughly hew’d out of Rocks and Beds of mineral Strata, discovering in the Fissures and angular Breaches, Variety of Flints, Spar, Ores, Shells, &c.

It is this sense of Man the Geologist discovering the structure of the earth beneath him and making that his theme, this romance of science, that imparts its peculiar excitement to Pope’s now-vanished Twickenham garden. An architecture without order, without rule—quite the opposite of what one would expect from the classicizing poet—was chosen to body forth an inquiry that, in due course, would gain the strength to challenge the biblical cosmogony. The impetus of that inquiry derived in part from antiquarianism and its allied sciences (in the spirit of figures like John Aubrey and John Evelyn) and in part from the direct legacy of Sir Francis Bacon.

For it was Bacon’s former laboratory assistant, Thomas Bushell, who, after repenting his former debauched life (Bacon was well known for his pederasty, and Bushell had entered his service at the age of fifteen, so we don’t need to be told what they meant by “debauchery”) and a period of hermit-like retreat on the Isle of Man, emerged from his seclusion, prudently married an heiress, and discovered a curious rock that he proceeded to beautify and to turn into a “waterworks”—in modern parlance, a complex water feature, in a desolate underground spot, with stalactites and other strange natural forms.

This was not unique in England. Petrifying streams (in which an object such as a hat, hung up for a while, becomes encrusted with lime) were associated with witchcraft. Mother Shipton’s Cave, in North Yorkshire, has been operating as a tourist attraction since 1630, officially the oldest such attraction in the country. Bushell’s waterworks at Enstone in Oxfordshire may have been somewhat older—“to enstone” may mean, apparently, “to petrify”—while the extraordinary cave complex at Wookey Hole in Somerset was inhabited in Roman times and before. (Its constant temperature of 52 degrees Fahrenheit makes it an ideal place to mature cheddar cheese.)

Enstone, then, is one of a group, a “desolate Cell of Natures rarities,” as Bushell described it, with human embellishments such as

artificial Thunder and Lightning, Rain, Hail-showers, Drums beating, Organs playing, Birds singing, Waters murmuring, the Dead arising, Lights moving, Rainbows reflecting with the beams of the Sun, and watry showers springing from the same fountain.

Among the beautifications was a silver ball kept aloft on a jet of water where “some-times fair ladies [who] cannot fence the crossing” are caught “flashing and dashing their smooth, soft and tender thighs and knees, by a sudden inclosing them in it.” The sexiness of this passage reminds us that the early holiday spots, such as hot springs, were places that tolerated, and even encouraged, licentious behavior. This is what the practical jokes such as water-squirts, built into the design, were about—an element of garden-making that has fallen into desuetude.

Advertisement

Todd Longstaffe-Gowan, who in his admirable English Garden Eccentrics introduces us to Thomas Bushell, among many others, clearly has some private criteria for what counts as material for inclusion on the dotty side. Pope, for instance, is not considered dotty, despite his degree of obsession. I think this is right: Pope’s place is not on the margin, where dottiness thrives, but at the center—wherever he hung his wig. If Pope’s heroes (figures such as Lord Bathurst) are not always our heroes, Pope’s enemies (say, Lord Hervey) stand very little chance of becoming our friends. Pope is always so vehement. If he is on one side of the argument, it requires a special effort to argue the opposite case.

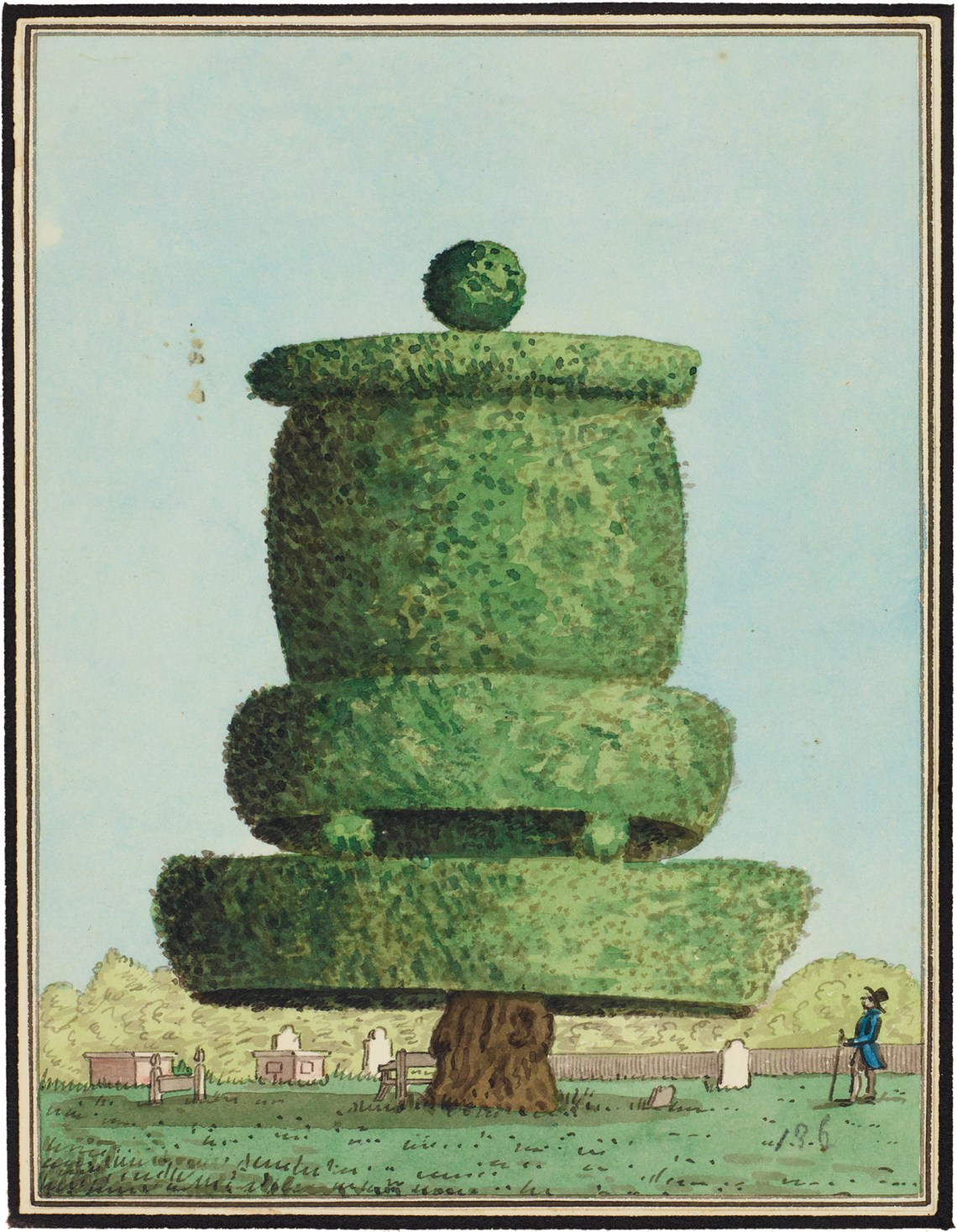

Consider the question of yew topiary, an art that Pope mocks. Not every tree or shrub will take kindly to a cutting regime. Yew is better than most. It has traditionally been cultivated in churchyards or enclosed gardens because its leaves are poisonous to cattle. It was valued all over Europe as the preferred wood for longbows, but after the bow went out of use as a weapon, yew trees retained or acquired a decorative purpose. They are long-lived and, once established, somewhat slow-growing—they don’t require trimming more than once a year. Shaped to resemble, say, chess pieces or peacocks (two popular themes), they soon lent an air of establishment, even antiquity, to a garden. But they were apt to divide horticultural opinion. Pope clearly thought they were lower-middle class and suburban:

People of the common Level of Understanding are principally delighted with the little Niceties and Fantastical Operations of Art, and constantly think that the finest is least Natural. A Citizen is no sooner Proprietor of a couple of Yews, but he entertains Thoughts of erecting them into Giants, like those of Guild-hall [famous figures of Gog and Magog].

What is being attacked here is inappropriate horticultural ambition. What is not, by any means, being attacked is the kind of horticultural ambition that led Lord Bathurst in 1720 to plant his colossal yew hedge at Cirencester, today at 45 feet the tallest in the world, 15 feet thick at the base, 510 feet long, and requiring two men twelve days for its annual trim. It was a good investment (Pope’s epistle to Bathurst was on the subject “Of the Use of Riches”) and continues to give pleasure. The longevity of yews is impressive—some of the trees, which began dying of a mysterious ailment in England last summer, are estimated to be a thousand years old. Where they have been shaped over the centuries, as in the gardens at Levens Hall in Cumbria (one of the most beautiful of English gardens and said to be the oldest topiary garden in the world), they sometimes, not surprisingly, begin to go their own way in the matter of shape. They become intractable and incomprehensible.

Nobody, I think, turns up his nose at a yew hedge, or at a pyramid balancing its base on a barely credible sphere. Nobody turns his nose up at abstraction in the garden, or the solid geometry of the clippers. What calls forth protest is the act of representation—a bush in the form of a dolphin, a shrub “tortured” into the likeness of a unicorn. But here is the popular gardening guru of the Victorian age, Shirley Hibberd, defending the art of the shears:

It may be true, as I believe it is, that the natural form of a tree is the most beautiful possible for that particular tree, but it may happen that we do not always want the most beautiful form, but one of our own designing, and expressive of our ingenuity.

This puts its finger on a distinction sometimes made between the natural beauty of a plant growing “the way it’s supposed to” and the pleasure to be gained from revealing some surprising capacity not normally seen, as when apples are induced to follow the curve of a crinkle crankle wall. The wall, with its serpentine design, makes a feature of the apple’s rigorous training—the tight sequence of annual cuts, the stretched wires, things ugly enough in themselves, for some tastes. But the freestanding fruit tree has its own vital regime: the grafting of the scion to the stock, the regular pruning of new growth, the decisions made as to the optimal size of the tree—decisions made at the breeding level, long before the shears come into play.

It has been observed of the English that their upper and lower classes in some matters share a particular taste that eludes the middle rank, the bourgeoisie. Toffs and touts, for instance, both on occasion wear bowler hats (toffs in the City, touts at the racecourse). The people in between do not. This exclusion of the middle can be seen in garden literature, where for decades a war was waged against carpet bedding, that is, the designing of a garden in great decorative blocks of color, using hundreds, maybe thousands of identical bulbs and annuals, which were replaced each season.

The disapproval of such bedding schemes was almost total, but the taste hung on in certain local government parks by the seaside, where gardeners delighted in recreating, in flowers, decorative clocks or the arms of the municipality. Inevitably, in the end, this prejudice against bedding came under attack, but from the top. It amused Lord Rothschild, a few years ago, to recreate the floral schemes of his ancestors at Waddesdon. It was the right house, and the right garden, for that overdue revolt. But it ought also to be said that summer bedding schemes have an unanswerable justification in resort towns where the gardeners are working specifically for the pleasure of summer visitors.

Visitors to Worcestershire may come across the gargantuan ruins of Witley Court, a nineteenth-century house so enormous that, when it partially burned down in 1937, nobody had the effrontery to rebuild it. The park and its colossal fountain remain, rivals to Versailles, with a stone group of Perseus and Andromeda estimated as “probably the largest sculpture in Europe” and one spout alone of which reached over a hundred feet “with the roar of an express train.”

The Earls of Dudley had bought and expanded this house (originally built in the seventeenth century), adding layer upon stylistic layer, extending terraces and colonnades, until the historic core of the building had probably been forgotten. The gardens were designed by William Nesfield, the High Victorian landscape architect, master of the preposterous parterre. But one remote section of the vastness displayed its art on a more modest, more human scale. This was “My Lady’s Garden,” named for Rachel, the wife of the Second Earl of Dudley, a woman determined to make herself useful, which she did as vicereine of Ireland: she founded Lady Dudley’s Scheme for the Establishment of District Nurses for the Poor in Ireland.

In her spare time at Witley Court, when she was not, as it were, trailing her fingers in the waters of the deafening fountain, Lady Dudley would comb the surrounding countryside, looking for topiary specimens in the places she preferred to find them—not in the nursery catalogs but in the gardens of the cottagers. It was another of these happy confluences of the taste of the poor and that of the very rich indeed. The cottagers appreciated Lady Dudley and spoke of her warmly decades later. And she no doubt appreciated them—to the extent that these things can ever be measured or described. The house was sold in 1920, and then came the great fire of 1937. Dereliction followed.

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Becoming Enid Coleslaw

Putin’s Folly

Descriptions of a Struggle