1.

Several of modern design’s most familiar shibboleths were not first stated as they are now commonly quoted. For example, Louis Sullivan’s supposed pronouncement “Form follows function” appears in his prophetic essay “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered” (1896) as “Form ever follows function,” a small but important distinction. Many Anglophones translate Le Corbusier’s definition of the house—une machine à habiter, first set forth in his book Vers une architecture (1923)—as “a machine for living,” whereas it properly means “a machine for dwelling in.” And despite Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s being credited with the aphorism Weniger ist mehr (Less is more), it was actually formulated by the eighteenth-century German poet Christoph Martin Wieland as Minder ist oft mehr (Less is often more). Similarly, Ornament ist Verbrechen (Ornament is crime) is the most famous thing never said by Adolf Loos (rhymes with “gross”), the early-twentieth-century Austro-Czech Modernist architect, interior designer, social critic, cultural agitator, and convicted pedophile.

Today Loos’s incendiary essay “Ornament and Crime,” which he first presented as a lecture in Vienna in 1910, is better known than his architecture. In this cleverly argued polemic, he draws subjective but intriguing links between decoration—of architecture, utilitarian objects, even the human body—and the rise of civilization: “I have made the following discovery and given it to the world: the evolution of culture comes to the same thing as the removal of ornament from functional objects.” This was a radical proposition at a time when design of all sorts, from high to low and from historicizing to avant-garde, was rife with applied decoration. Coming after Loos’s laser-like critiques of everything from footwear to glassware to underwear—the texts of which are included with the essay in a recent Penguin paperback—“Ornament and Crime” consolidated his renown as a fearless gadfly.

Loos astutely established his professional practice in Vienna, capital of the multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had been cobbled together during the nineteenth century from several Central European polities, including his native Moravia, and was ruled from the revolution of 1848 to World War I by the long-lived and reactionary emperor Franz Joseph I. At the empire’s epicenter, Loos availed himself of numerous Jewish patrons who were drawn there by commercial interests and were unusually receptive to advanced directions in art. They made up a significant proportion of his clientele throughout his career, a tendency often repeated in the history of Modernism.

Although the Viennese upper classes remained inherently conservative, the city seethed with artistic ferment that arose in opposition to the mossbacked academicism of its state-sponsored culture. In 1897 a fractious coalition of painters, sculptors, and architects resigned from the establishment Association of Austrian Artists and formed the Vienna Secession, through which they sought to advance an alternative aesthetic that reflected their modern attitudes. Six years later several Secession members founded a decorative arts affiliate, the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshop), to put their reformist theories into action by manufacturing and selling objects that embodied their new philosophy.

The Secession’s mercantile offshoot furthered its conviction that ornament must be fully integrated into a design and strictly controlled. This paralleled Loos’s radical experiments in paring down architecture to its most basic elements and purging it of what he considered to be socially harmful propensities. Yet he decried the Wiener Werkstätte’s output as insufficiently different from the routine consumer goods it purported to improve upon, and mockingly referred to the group as das Wiener Weh (the Viennese woe).

He wanted a clean sweep—the complete rejection of needless surface additions to architecture and furnishings. This has become his most enduring legacy as well as the most controversial principle of Modernism: the moral superiority of refusal. Loos’s stance was widely cited in the 1970s and 1980s during the brief ascendancy of Postmodernism, which called for a turn away from High Modernism’s enforced austerity and a return to pattern and ornament in the applied arts. Although Postmodernism helped to free architecture and design from the prohibition against surface embellishment that had prevailed since the 1930s—in no small part because of the Museum of Modern Art’s exclusionary preference for the reductive International Style (and because it was much cheaper to build without labor-intensive decorative flourishes)—the residue of MoMA’s narrow-mindedness and Loos’s oft-misquoted catchphrase were underscored by a recent coffee-table book titled Ornament Is Crime: Modernist Architecture (2017).

Contemporary critics have discerned strong indications of misogyny and racism in some of Loos’s positions. Although his attitudes toward women were not much different from those of his Viennese contemporary Sigmund Freud and should be understood (though hardly excused) within the values of their cultural milieu, his condescending if not contemptuous appraisal of indigenous societies is harder to rationalize today. For instance, he considered tattooing—a Bronze Age introduction that recurred as a nineteenth-century fetish and is now a postmillennial mania—to be a reliable indicator of human devolution. As he wrote in “Ornament and Crime”:

Advertisement

The child is amoral. For us, so is the Papuan. The Papuan slaughters his enemies and devours them. He is not a criminal. But if modern man slaughters and devours someone, he is a criminal or a degenerate. The Papuan tattoos his skin, his boat, his rudder, in short everything that lies to hand. There are prisons in which 80 per cent of the inmates have tattoos. The tattooed people who are not in jail are latent criminals or degenerate aristocrats….

The man of our own times, who follows his innermost urgings to smear the walls with erotic symbols, is a criminal or a degenerate. What is natural in the Papuan and the child is a manifestation of degeneracy in modern man.

In his excellent compendium Essays on Adolf Loos, Christopher Long, a professor of architecture at the University of Texas at Austin, notes:

The writings of the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso…probably inspired Loos’s fusing of ornament and the behavior of the criminal underworld…. In L’uomo delinquente [The Criminal Man]…he writes: “Tattooing is one of the striking symptoms of humans in a raw state, in their most primitive form.”

No less an expert on (and agent of) societal decline than Donald Trump has expressed a typically opportunistic view of the recent resurgence of this ancient form of self-ornamentation. Michael Wolff reported in Landslide: The Final Days of the Trump Presidency (2021) that although the ex-president was repelled by the widespread fondness for inking among his political base, he regretted not having invested in a chain of tattoo parlors to profit from it.

2.

Adolf Franz Karl Viktor Maria Loos was born in 1870 into a Catholic family in the city of Brno, now part of the Czech Republic. His father, a stonecutter, died at an early age, after which his mother assumed control of the family business. The young Loos wanted to become an architect, but as a troubled adolescent he never completed his secondary education. Thus disqualified from earning a higher degree, he took sporadic architecture courses at Dresden’s Technical University and Vienna’s Academy of Arts. But he was a natural autodidact, and his extraordinary conceptual abilities compensated for his lack of formal education. At twenty-two he took off for the US to visit an uncle who had immigrated to Philadelphia.

He then went to see the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago but was most impressed by the innovative tall buildings of that burgeoning metropolis, rather than the pompous Beaux-Arts Classicism of the widely praised “White City.” Louis Sullivan denounced what he called this “Columbian Ecstasy” as “bogus antique” and accurately predicted that “the damage wrought by the World’s Fair will last for half a century from its date, if not longer.” Eventually Loos was hired as a draftsman in a New York architectural office, and during his three-year sojourn in this country he came to admire Americans’ open-minded acceptance of pragmatic modernity.

After his return to Vienna, Loos began writing provocative columns on design for the city’s leading liberal daily, the Neue Freie Presse, and soon became a cultural celebrity, a position he maintained for the rest of his life thanks to his keen instinct for publicity. His first architectural jobs were for residential and commercial interiors within existing buildings: a café, a villa, two apartments (one of them for himself and his first wife, Lina Obertimpfler), and an example of the new tavern format known as an American bar, differentiated from the traditional sit-down Lokal by its stand-up counter, a New World innovation previously unknown in continental Europe. During his early career he completed just one freestanding structure: the imposingly foursquare, corner-turreted Villa Karma of 1904–1906 in Clarens, Switzerland, a thoroughgoing expansion of a smaller house on the shores of Lake Geneva.

It was built for Theodor Beer, a physiology professor at the University of Vienna, who in 1905 was tried for molesting two boys he had photographed nude and for being a practicing homosexual. In 2012 the architectural historian Frederic J. Schwartz revealed that Loos was implicated in the case, both as a character witness for Beer and because (as he later confessed to his second wife, the operetta star Elsie Altmann) he hid his client’s incriminating pictures to prevent their discovery. Beer was convicted, served a prison sentence, went bankrupt, and killed himself in 1919, as his pregnant, much younger wife had done soon after he was found guilty. This sad chain of events now seems eerily predictive of the sordid scandal that engulfed Loos five years before his death and cast a permanent shadow over his reputation.

Loos’s big breakthrough had come with his Goldman & Salatsch building of 1909–1911 in Vienna, familiarly called the Looshaus. Still his best-known architectural work, it is the subject of a definitive monograph by Long. This mid-rise, mixed-use scheme was erected on Michaelerplatz, a semicircular plaza laid out in 1725 by the architect Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach as a forecourt for the St. Michael’s Wing, his proposed addition to the Hofburg, the sprawling complex that served as the Habsburg dynasty’s winter residence as well as the empire’s governmental headquarters. His grandiose Baroque design, which features a floridly embellished concave façade surmounted by three domes, was not executed until 1889–1893 (with Fischer von Erlach’s original plans altered by Franz Joseph’s court architect, Ferdinand Kirschner).

Advertisement

The palace extension was thus less than twenty years old when the proprietors of the Goldman & Salatsch men’s clothing company announced a design competition for a new flagship store on the prestigious site directly across from the Hofburg. Bounded by two streets that radiate outward from Michaelerplatz, the wedge-shaped plot determined the project’s basic configuration. The building is equally divided between its dual functions, with the lower three stories occupied by the upscale clothier and orchestrated by the architect into one of his brilliant multilayered spatial compositions to accommodate reception areas, display spaces, changing and fitting rooms, behind-the-scenes ateliers, and storage. Above them are another four floors of spacious apartments and offices, capped by an attic under a mansard roof, where tailoring apprentices originally worked.

The structure is supported by an internal reinforced concrete framework, then a relatively new concept. (The first skyscraper to employ that transformative engineering method was Elzner & Anderson’s sixteen-story Ingalls Building of 1903 in Cincinnati.) But what really grabbed public attention was the Looshaus’s startlingly stark exterior, the white stucco upper half of which is so devoid of the period’s usual florid ornamentation—even basic window frames and narrow “string-course” moldings were omitted—that Viennese wits dubbed it das Haus ohne Augenbrauen (the house without eyebrows). But if it lacked those defining features, it had a full beard, as it were, an impression given by the lushly streaked dark-and-light-gray marble panels that cover the building’s lower half down to the sidewalk. That commercial zone is dignified by a monumental though much simplified Classical order that contrasts dramatically with the protomodern grid of square apartment windows punched through the walls above it. Franz Joseph was so enraged by the Looshaus that he henceforth refused to leave the Hofburg via the Michaelerplatz portal in order to avoid seeing this affront to civic decorum.

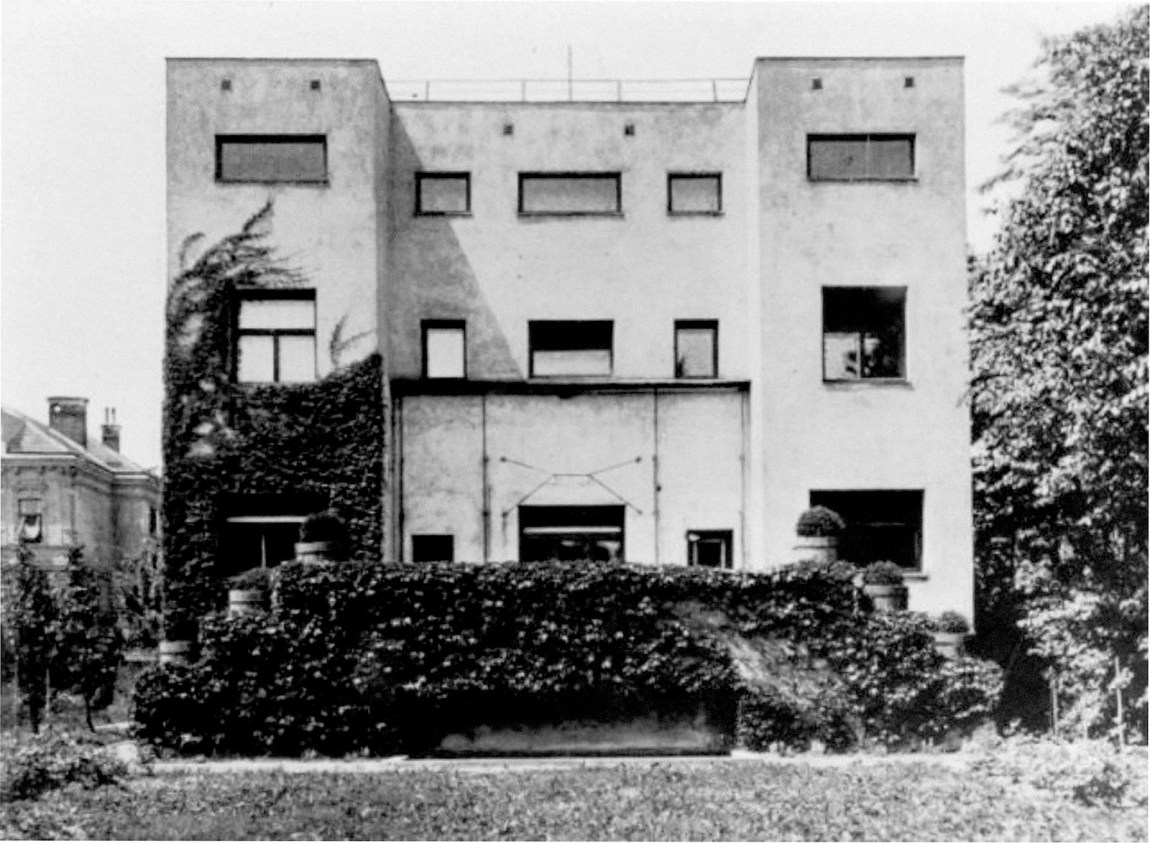

Loos’s oeuvre was primarily residential, and one of his most audacious compositions was the Steiner house of 1910 in Vienna. Its charming two-story street front, with a metal-clad half-barrel-vault roof that imparts the air of a storybook cottage, fits right into its quiet neighborhood in the city’s affluent Hietzing district, not far from Gustav Klimt’s villa and Schönbrunn Palace, the summer residence of the Habsburgs. But the sloping garden side of the Steiner house is stunningly different from its modest façade. There, a sheer cliff of white stucco rises three stories between two squared-off towers that frame a wider, recessed central portion with paired rectangular windows as unadorned as those at the Looshaus. Understandably, the rear of the Steiner house has been reproduced countless times in architectural history books as a foundational example of minimalism long before the term existed.

Particularly fascinating are Loos’s 1927 plans for an unexecuted Paris house for the expatriate African American entertainer Josephine Baker. Flat-roofed, rectangular in ground plan, with a cylindrical tower at one corner, its exterior would have been boldly surfaced with alternating horizontal bands of black and white marble. The most remarkable feature of Loos’s veritable domestic stage set was to be an indoor swimming pool illuminated by a skylight and accessible only to the owner through her private quarters, but not to guests. They, however, could gather in a peripheral corridor to watch this joyous exhibitionist cavort: large plate-glass windows set beneath the waterline promised an aquatic spectacle that capitalized on La Baker’s image as a free spirit who personified the 1920s Années folles.

3.

Unlike many of his most talented contemporaries, especially Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and Josef Hoffmann, Loos did not insist on outfitting his architecture solely with designs of his own, even though he devised many superb pieces of furniture, including several distinctive six- and eight-legged round tables. He tended to be disdainful of rapid changes in fashion, and in “Ornament and Crime” deplored novelty-seeking consumers who

want to have something new, “fashionable,” “modern.” They even want to have an “artistic design.” And in four years they will want another “artistic design,” because they will find that their furniture is entirely unmodern, and very new artistic designs are being made. That’s terrible! It’s a waste of energy, work, money; this does terrible economic damage.

Too few historians have emphasized that Loos’s objection to extraneous ornament was based in part on economics, not solely morality. He was well aware that most people could not afford the costly handwork favored by the English Arts and Crafts Movement in reaction to the cheap machine-made goods that proliferated during the Industrial Revolution, and that the crafts-centered Wiener Werkstätte, despite the up-to-date appearance of its products, was thus a socially retrograde rather than progressive endeavor.

An Anglophile who dressed in bespoke suits, Loos believed that “an English club armchair is an absolutely perfect thing.” This enthusiasm was later shared by Le Corbusier, who like Loos often specified generic leather-upholstered club chairs from the stolidly middle-class London furniture retailer Maple & Co. Another taste the two architects shared was an admiration for the elegantly timeless yet democratically affordable bentwood furniture made since the mid-nineteenth century by the Vienna-based firm Thonet, which epitomized the Modern Movement’s egalitarian but sometimes elusive desiderata of beauty, utility, and economy. Loos wrote in “Ornament and Crime,” “A Thonet chair is the most modern chair.”

Although a pioneering minimalist, Loos was no stranger to luxury and refinement. He believed that the exteriors of new urban architecture should be recessive enough to create a harmonious ensemble accented by the occasional singular landmark, no matter how elaborate the interiors of those buildings might be. He never considered the Looshaus to be a disruptive interloper, merely a neutral element. Undeterred by restrictive notions of modernity, Loos regularly incorporated a very specific roster of antiques into his decorative schemes. English Queen Anne and Chippendale high-backed chairs were recurrent components, as were Chinese porcelains, Dutch brasses, and rugs from the Near East and Central Asia, which he often selected for exact positions within his carefully considered household ensembles. He eschewed both the cluttered eclecticism of the earlier Makartstil (the fashionable Aesthetic Movement variant popularized by the mid-nineteenth-century Viennese painter and decorator Hans Makart) and the sparse functionalism of the later International Style. Thus Loos’s rooms, though always restrained, were also much more livable than puritanical Modernist environments that sacrificed comfort to appearance.

Handsome color photographs of Loos’s surviving interior settings, taken by Philippe Ruault, help make Ralf Bock’s new monograph, Adolf Loos: Works and Projects, an indispensable (though atrociously translated) reference. They convey an accurate idea of the nuanced chromatic values of Loos’s work that get lost in the period black-and-white pictures that were long our sole source of visual information about it. As we can see from these more realistic views, although Loos eschewed applied ornament he exploited the inherent decorative potential of wood grain and marble patterning in wall paneling and floors, along with the deeply saturated colors he favored in those materials. This resulted in the characteristic darkness of his interiors, which convey an enveloping sense of protective enclosure quite different from the light-flooded transparency we usually associate with Modernist interiors.

4.

Apart from his impassioned advocacy of simplification, Loos’s greatest architectural contribution was what he termed der Raumplan—“the room plan,” in its literal but wholly inadequate English translation. Whereas we might think of a room plan as a two-dimensional diagram depicting the layout of an interior space, Loos had something quite different in mind. He conceived architecture in three dimensions—an ability not to be taken for granted among his co-professionals—and felt that too much of buildings’ internal volume was wasted by ceilings needlessly high for the functions carried out beneath them. He realized that a good deal more usable area could be coaxed out of a structure without expanding its outer dimensions if multiple interstitial levels were introduced rather than the usual laterally uniform stories.

In her anecdote-packed and highly revealing memoir Adolf Loos Privat (The Private Adolf Loos, 1936), the architect’s third and last wife, the Czech photographer and writer Claire Beck Loos (who was Jewish and was murdered in a Nazi concentration camp at age thirty-seven), records the architect’s own explanation of the Raumplan concept:

The ship is the model for a modern house. There, space is totally utilized, no unnecessary waste of space! Nowadays, with building sites being so expensive, every inch of space must be used…. I have not only got rid of ornamentation, I have discovered a new way of building. Building into space, the Raumplan, spatial design. I do not build in flat planes, I build in space, in three-dimensions. This is the way I manage to accommodate more rooms into a house. The bathroom does not need to have a ceiling as high as the living room…. The rooms are nested into each other, each has a height and size corresponding to its purpose….

This reference to ship design echoes Le Corbusier’s contemporaneous praise for nautical prototypes in Vers une architecture, and his Purist houses of the 1920s with their horizontal handrails have been likened to the superstructures of ocean liners, illustrations of which he included in that hugely influential publication as perfect examples of rational design in the industrial vernacular.

Loos’s architecture was distinguished not only by its severe exteriors—cubic, flat-roofed, and clad in white stucco, anticipating Le Corbusier’s houses of his so-called Heroic Period—but also by a multiplicity of discrete spaces of varying heights fitted together with the ingenuity of a Chinese puzzle box. This provides a direct contrast to the lateral flow of interconnected spaces pioneered by Frank Lloyd Wright around 1900 and codified by Le Corbusier as le plan libre (literally “the free plan,” though today more commonly called “open concept” in English), one of his canonical “Five Points of a New Architecture” (1927), and thereafter a central tenet of Modernism. A bastardized application of Loos’s Raumplan is detectable in the contractor-designed split-level houses that became popular in suburban American subdivisions after World War II. Their greater distribution of interiors on multiple levels—though arranged without the intricacy of Loos’s schemes—could give growing families more separate spaces without a prohibitive increase in overall expense, because the building’s footprint did not need to be larger than that of the usual two-story tract house.*

How the Raumplan was implemented is made incomparably clear in Adolf Loos: The Last Houses, an illuminating monograph by Long, which analyzes the architect’s late series of intricately worked-out residential designs. One of the several well-illustrated projects included here is the Villa Winternitz of 1931–1932, designed by Loos in collaboration with the generation-younger Czech architect Karel Lhota, with whom he had already worked on the better-known Villa Müller of 1928–1930, also in Prague.

Color photographs of the Villa Winternitz reveal decor notably less lush than the colored marble and rare wood paneling of Loos’s earlier interiors. In their place we find humble Flemish bond red brick employed to create a dado—the traditional waist-high differentiation of a vertical wall treatment—with plain white plaster extending above it to the ceiling. This visual tour through the structure begins with an entry vestibule reminiscent of a terra-cotta-hued Mondrian, which leads via a narrow stairway (Loos believed that interstory steps need be no wider than a ship’s passageway) up to a mezzanine that overlooks a cozy dining room with a redbrick hearth down to the left, and up to the right to a sun-flooded living room, a vertical progression that feels like an ascent to domestic heaven. It seems eminently habitable, and much more to contemporary tastes than some earlier efforts by the architect that now feel rather dated.

5.

Loos died a year after the completion of the Villa Winternitz at age sixty-two, nominally from a stroke but presumably from the tertiary effects of syphilis, which he likely contracted at a brothel in his early twenties. That once-incurable venereal disease is thought to have contributed to the dementia that he exhibited by the late 1920s, although his behavior could be erratic even before then.

The most troubling aspect of assessing Loos is his predation of underage girls, which in 1928 led to his prosecution and conviction on charges of child sexual abuse. In Adolf Loos on Trial, Long goes back to what remains of the original legal records and gives us a scrupulously laid out but altogether dispiriting account of this sorry footnote to modern architectural history.

As Long documents, there was widespread child prostitution in early-twentieth-century Vienna, where youngsters of both genders often wandered unsupervised through the extensive public park system. Although this clandestine pedophile subculture has led some apologists to argue that Loos’s behavior must be seen within its time and place, Long refutes

those who claim…that Loos’s alleged crimes with children were simply a common practice at the time and had a different value then. Such relativizing has import for cultural understanding. But sex with minors in Austria in the 1920s was viewed unequivocally as an offense.

Elsewhere he writes:

The authorities, based on today’s practices and even what was being recommended by the professionals who dealt with children in such cases at the time, mishandled the investigation. They should have immediately called in the child psychiatrists, and they should have conducted the questioning with greater care. Whether the girls [aged eight and ten] were telling the whole truth is, from our remove, impossible to say. But anyone nowadays reading the police file objectively and carefully will come away with a strong sense of Loos’s guilt.

The graphic evidence against the defendant in the court file is powerful, and it confirms that he should have been found culpable of the two most serious charges: having “sexually abused persons under the age of fourteen years for his own pleasure” and inducing them “to engage in indecent acts.” As it was, he was judged “guilty of causing [the girls to commit] obscene acts” and was given four months in prison. (The legal distinction between “indecent acts” and “obscene acts” may be hard for lay readers to discern, but Long quotes enough explicit and stomach-turning testimony from Loos’s victims to leave no uncertainty about his final assessment.) However, accounting for time already served and with the rest of the sentence suspended for three years of probation, Loos was released, doubtless because of his prominence. Long concludes his skillful analysis of this indefensible episode by acknowledging that it is now impossible to be certain what transpired between Loos and the minors he claimed to have been interested in only as nude models for his sketching, as if he were some avuncular Egon Schiele.

The supercilious replies Loos gave under oath at his trial—which bring to mind Oscar Wilde’s flippantly self-destructive performance on the witness stand three decades earlier—only increase one’s impression that he saw nothing fundamentally wrong with indulging his natural instincts. With a sour irony that recalls the flavor of Loos’s seemingly offhanded but precisely aimed feuilletons about contemporary culture, Christopher Long, our finest present-day interpreter of this complex, contradictory, but ultimately confounding modern master, gets it absolutely right: “It may be that there is no truth after the fact without ornament.”

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Becoming Enid Coleslaw

Putin’s Folly

Descriptions of a Struggle

-

*

See my “Living Happily Ever After,” The New York Review, April 21, 2016. ↩