Toward the end of Penelope Fitzgerald’s 1980 novel Human Voices, a fictionalized account of her time working at the BBC during World War II, an executive named Jeff Haggard finds himself standing outside Broadcasting House, the organization’s London headquarters, looking up at the stone figures of Prospero and Ariel that have stood above the entrance since 1933. Haggard—usually referred to simply as DPP, an abbreviation of Director of Programme Planning, one of Fitzgerald’s jokes about BBC nomenclature—muses on the sculpture, which was carved by the English artist Eric Gill:

Prospero was shown preparing to launch his messenger onto the sound waves of the universe…. And when this favored spirit had flown off, to suck where the bee sucks, and Prospero had returned with all his followers to Italy, the island must have reverted to Caliban. It had been his, after all, in the first place. When all was said and done, oughtn’t he to preside over the BBC? Ariel, it is true, had produced music, but it was Caliban who listened to it, even in his dreams. And Caliban, who wished Prospero might be stricken with the red plague for teaching him to speak correct English, never told anything but the truth, presumably not knowing how to. Ariel, on the other hand, was a liar, pretending that someone’s father was drowned full fathom five, when in point of fact he was safe and well. All this was so that virtue should prevail. The old excuse.

Prospero, Caliban, Ariel: this Shakespearean triad corresponds neatly to the BBC’s original mandate, laid down by its founding chief executive, John Reith: Inform, educate, entertain. Yet Fitzgerald identifies a contradiction: Prospero will inform, Ariel will entertain, but Caliban is to be educated—two active figures and one passive. This seems unjust, Haggard thinks: To whom should the BBC belong if not the listener?

The British Broadcasting Company began life in 1922 as a commercial entity operating under license from the General Post Office. Its first engineer had worked for the Marconi Company, pioneer of wireless radio communication, and understood the new technology in terms that sound almost startlingly like those of our own era: a “platform” that could enhance “the social life of the people.” In 1927 it became a corporation—a public entity, still licensed by the post office but now operating under royal charter (actually issued by Parliament, not the Crown) and largely self-funding through royalties on sales of radio sets and a “license fee.” This permit was essentially an annual flat tax on every household that owned a wireless, later a TV set, and now any device with a screen used to play BBC content.

The royal charter and the license fee are crucial parts of the flawed genius of the BBC’s institutional architecture. The charter subjects the broadcaster to periodic government scrutiny. The license fee, currently £159 per household per year, notionally gives every BBC listener and viewer (which in practice is almost everyone in the UK) a stake in the corporation—not a share, by any means, but a sort of proxy for public ownership.

The arrangement poises the BBC delicately, confusingly, in a special zone of ambiguity. Each of its three implicit owners could be excused for thinking that it belongs to them above all. Yet the BBC belongs to none, as long as the spell lasts.

Like many of the BBC’s first generation of executives, Reith was a decorated, wounded veteran of World War I who had returned from its battlefields with a powerful belief in the need to renew civilization and redeem its cultural heritage. He was also the devout son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister, and his mantra of “inform, educate, entertain” was very much in that order—with entertainment a grudging, concessionary third. This ethos remains part of the BBC’s “public service” mission, shaping the nature of the institution; one early producer characterized it as “one-third boarding school, one-third Chelsea party, one-third crusade.” (Fitzgerald, for her part, described the organization as “a cross between a civil service, a powerful moral force, and an amateur theatrical company that wasn’t too sure where next week’s money was coming from.”)

But what does public service mean in broadcasting? A tempting analogy is always with the National Health Service—an almost universally loved institution in British society, the last edifice still standing (just barely) of the social-democratic “New Jerusalem” that Clement Attlee’s postwar Labour government aimed to build. The NHS does appear largely unassailable. Not even Margaret Thatcher or any of her followers since really dared attack the fundamental principle of taxpayer-funded care, free at the point of delivery. If you squint at the BBC, it can appear to occupy a similar space in British life: an admired institution paid for by public subscription to provide a universal and popular service.

Advertisement

Two centennial histories—David Hendy’s The

BBC: A Century on Air and Simon Potter’s This Is the

BBC—reveal the ways that this analogy fails. There is a reflex, mainly among Britain’s educated elite, to regard the BBC as an avatar of all that is best about the country’s traditions of fairness, decency, and civility. The view owes something to executive self-pleading whenever the royal charter falls due for renewal: a BBC chairman told a parliamentary committee in 1977 that the corporation provided the “social cement” holding the country together. In a nation as self-consciously divided by class as Britain, the notion of the BBC as a provider of organic community is a comforting one.

I feel the pull of this belief myself, even as I have grown more suspicious of its neo-Reithian paternalism. I was a beneficiary of the BBC’s brilliant children’s TV programming from the Sixties onward, shows—such as Blue Peter, Jackanory, and Vision On—that made storytelling, art, and crafts central parts of elementary school–age viewing and a great counterweight to the imported, sugary diet of cartoons. And I was one of millions who never missed the Saturday evening screening of Doctor Who, indelibly marked by that eerie, churning early electronic soundtrack by Delia Derbyshire of the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop. And what was Saturday night without the popular family game show The Generation Game?

One of the pleasures of these two books, especially for any British reader raised on BBC content, is that both opt for a chronological approach that involves extended tours of notable shows and their personalities and producers. Hendy is the more gifted writer, with an eye for amusing details and an ear for the voices of performers and program-makers. But Potter’s more schematic approach sometimes provides a clearer picture. He is consistently better at following the money, as in his succinct account of budget cuts from the Thatcher era onward that resulted by 1991 in nearly a third of the broadcast hours on the two BBC networks that then existed being filled with repeats.

Unlike Hendy’s prose, though, Potter’s occasionally lapses into the lifeless idiom of an HR department memo. When, in 1932, a pioneering head of the Talks department named Hilda Matheson fell out of favor and left the BBC, he explains, “This was partly due to her left-wing leanings, but gender discrimination also played a role.” Matheson appears as a much more fleshed out character in Hendy’s alternate account, which includes a photo portrait of her with fashionably bobbed hair and her arm around her dog, Torquhil, a regular in the office. Another frequent visitor was Vita Sackville-West, a prolific Talks contributor and also, as Hendy discloses, an amour of Matheson’s. Much later in his book, in a discussion of the BBC’s editorial policy, Hendy cites the influence of Matheson’s commitment to, in her words, “express all the most important currents of thought on both sides, preserving a carefully balanced diversity.” As for what part “gender discrimination” may have had in her departure, Hendy makes no mention.

To travel back through the BBC archives is to realize just how ancient are some of its longest-running radio shows: the magazine program Woman’s Hour has been on air since 1946; the radio soap opera of rural life The Archers started a year before Elizabeth II came to the throne, and it has survived her seventy-year reign. Taking this virtual studio tour is a reminder, also, of some of the corporation’s less glorious creative decisions, such as BBC TV’s continued commissioning of The Black and White Minstrel Show from 1958 until 1978, a period that included the Notting Hill race riots, Enoch Powell’s race-baiting “Rivers of Blood” speech in 1968, and the rise of the far-right National Front as a serious electoral threat.

Egregious as that decades-long error of judgment was, no blemish should obscure the extraordinary record of BBC drama. The BBC’s TV adaptations brought Shakespeare’s plays (several produced and directed by Jonathan Miller) into the living rooms of Britons who were unlikely ever to attend a stage production of the RSC. The heyday of Play for Today’s “engaged” social realism in the Sixties bequeathed a tradition at the BBC that was taken up by the dark edginess of work by Alan Bleasdale, John le Carré, and Dennis Potter. The career of screenwriter Andrew Davies, master of the costume-drama adaptation of literary classics—familiar to American viewers through PBS’s Masterpiece Theatre series—would be unthinkable without the institutional backing of the BBC.

The same could equally be said of David Attenborough, who started his BBC career in the early 1950s as a producer after flunking a screen test because someone judged his teeth “too big.” Evidently, another program-maker later thought better of that. As Potter too hesitantly reports, “Some thought that only the BBC could have made Life on Earth.” Everyone thinks this, just as everyone regards Attenborough as a national treasure—perhaps an international one, at this point. Arguably, America’s PBS and its radio equivalent, NPR, along with Canada’s CBC and Australia’s ABC, would not exist without the BBC’s model of public-service broadcasting. That example is part of what UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan meant when he called the BBC “perhaps Britain’s greatest gift to the world” in the twentieth century.

Advertisement

Attenborough also happens to be a very Reithian character, a moralist of that old BBC ethos: in effect, an Ariel who would be a Prospero. As early as the 1960s, when Auntie—to use the affectionate yet irreverent nickname for the BBC—was coming under ever-greater pressure to get hip to television’s seemingly inexhaustible potential for mass entertainment, Attenborough denounced the appointment of a former commercial TV chief executive to lead the BBC as akin to “appointing Rommel to command the Eighth Army.”

Attenborough’s fear proved overblown, but the reference to World War II is revealing. The BBC’s status as both a beloved domestic institution and a valued foreign service was never more solid than in wartime, which folded the BBC into a Churchillian mythology of Britain as the plucky lone holdout against the menace of Nazism. World War II became, in effect, the BBC’s finest hour.

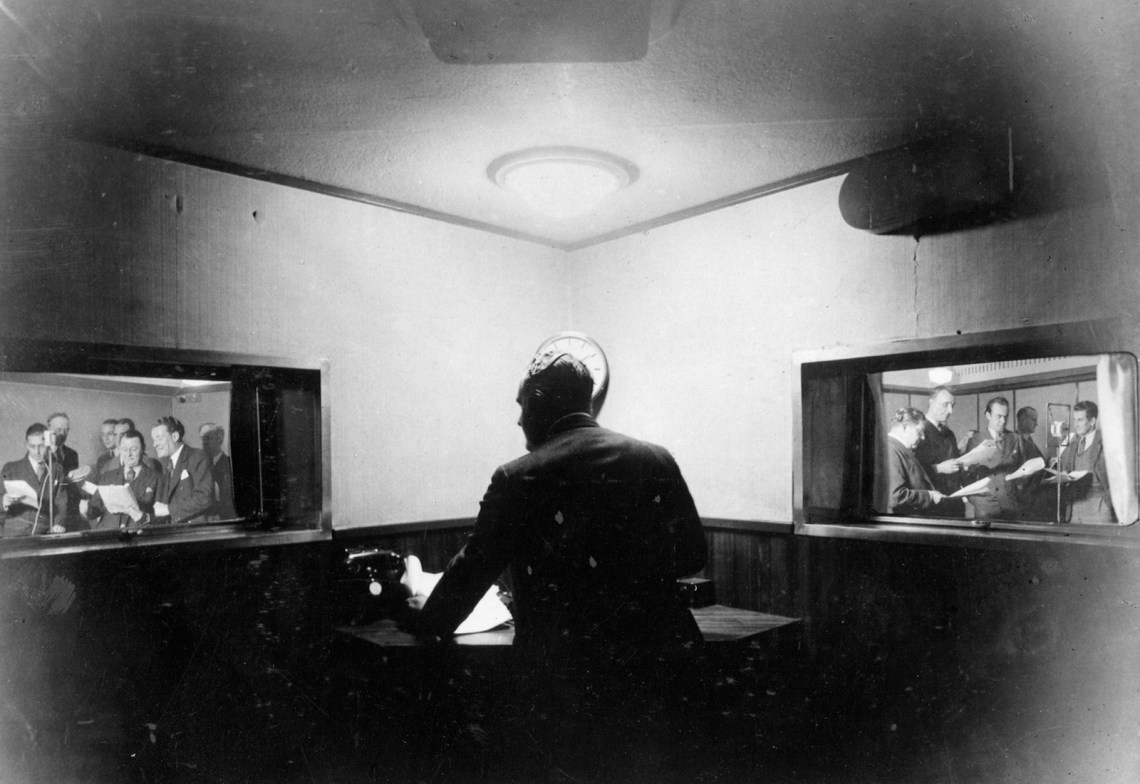

Just before the war, three quarters of Britain’s 12 million households had a wireless. Televisions had just become commercially available in the late 1930s, and at most only 25,000 relatively affluent households with receivers and within range could access the pioneering transmissions from Alexandra Palace, or “Ally Pally,” atop Muswell Hill in North London. When war came, the natural decision was to close down TV and make radio the medium of Britain’s de facto Popular Front against fascism.

The British government effectively nationalized the BBC, taking over its funding (the license fee was replaced by direct grant for the duration of the war) and assuming much more direct editorial control through a body known as the Political Warfare Executive, which acted under the aegis of the Ministry of Information. The PWE had offices in Bush House, the BBC’s Aldwych-based administrative and production center for foreign-service broadcasting, where the executive’s German section was led by Richard Crossman, who became an influential Labour Party politician after the war. But even under this close supervision, the BBC maintained a vital degree of editorial independence—as one of the PWE’s own chiefs declared, “Credibility is our weapon: we have got to be believed. We are not going to tell these untruths.”

Despite the Orwellian echoes in all of this, both Hendy and Potter largely overlook the BBC career of George Orwell himself. The veteran of the Spanish Civil War worked as a producer of guest essays broadcast by the BBC’s Eastern Service from 1941 to 1943. (No doubt his employers considered his prior experience as a colonial police officer in Burma a relevant qualification.) Orwell’s account of the job provides a fascinating insight into the doubleness of the BBC’s wartime activity. “One rapidly becomes propaganda-minded and develops a cunning one did not previously have,” he wrote in his diary. “I am regularly alleging in all my newsletters that the Japanese are plotting [to] attack Russia,” even though “I don’t believe this to be so.”

“All propaganda is lies, even when one is telling the truth,” Orwell concluded, but for a time, his own Popular Front sensibility permitted some equivocation: “I don’t think this matters so long as one knows what one is doing, and why.” That assurance couldn’t last—Orwell knew that his own job involved suppressing the anti-British messages of Gandhi and other pro-independence leaders in India. “At present I’m just an orange that’s been trodden on by a very dirty boot,” he wrote to a friend. When finally he had had enough, his resignation letter in September 1943 argued mildly that “by going back to the normal work of writing and journalism I could be more useful than I am at present.” He did get back to work for the Labour newspaper Tribune and on Animal Farm—though his experience at the BBC surely shaped his conception of the Ministry of Truth in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

As Orwell no doubt understood, he was only one cog in a great machine. The war embedded the BBC in British life not only as a trusted news service but also as the supplier of morale-boosting popular entertainment. At the same time, the European Service, which began shortly before the war, was rapidly expanded to broadcast to the Continent in wartime. Even propaganda could be a two-way street: Winston Churchill’s famous two-fingered V-for-Victory sign originated with an enterprising BBC Belgian-service announcer’s 1941 campaign to encourage anti-Nazi graffiti, soon replicated by the other foreign-language services, which resulted in Vs chalked on walls all over occupied Europe. The initiative was canceled when it became clear that hapless civilians were unnecessarily falling foul of the Gestapo.

Yet this was only the beginning of BBC-enabled resistance activity. The European Service developed a system of delivering instructions to partisans encoded in musical selections. According to Hendy, these transmissions were so effective that within twenty-four hours of D-Day in 1944, they had helped coordinate more than a thousand acts of railway sabotage on the Continent. With the campaign to liberate Europe unfolding, care had to be taken, as one BBC supervisor noted, not to repeat mistakes like the occasion in 1943 when an unwitting producer played the less scratched B side of a record instead of the intended A side—which resulted in Polish partisans blowing up the “wrong bridge.”

Less admirably, this practice continued deep into the cold war. From 1948 the BBC was using its foreign-language broadcasts in countries behind the Iron Curtain to send coded messages to agents of the MI6 secret service. And into the 1950s the BBC assisted Britain’s anti-Communist counterinsurgency efforts in the empire’s colonies. The head of the BBC’s East European Service was transferred for a year to run psyops for the Colonial Office. On his return in 1955, he was appointed head of the corporation’s Overseas Services.

As revolving doors go, this seems a good deal less savory than Reith’s own appointment as information minister in 1940 and his later elevation to the House of Lords. In the words of the BBC’s wartime chairman, the war effort required that the “silken cords” tying the broadcaster to the national interest as defined by the government sometimes became “chains of iron.” But the demands of wartime news coverage did lead to remarkable achievements by the BBC—including the innovation of equipment for “outside broadcasting” that, while absurdly unwieldy by today’s standards, at least did not weigh several tons. The innovation permitted such extraordinary moments in modern media history as the BBC’s Robert Reid live reporting on General Charles de Gaulle’s triumphant entry into Notre Dame in August 1944—“in what appeared to me to be a hail of fire from somewhere inside the cathedral.” As Hendy relates, Reid was still crouching for cover when he “told listeners that the shouting and the cheering they could hear in the background was the sound of four of the [German] snipers being caught and hauled away.” Intent upon his great symbolic spectacle of reconquest, “striding down the central aisle, shoulders flung back,” de Gaulle had somehow dodged their bullets.

As that passage suggests, Hendy’s more writerly instinct for a telling anecdote makes the BBC’s war the best section of his engaging book—but then the wartime material itself reflects a high point for the corporation. The BBC was then a national institution that mattered globally. Its journalistic standards made its news service essential to the defeat of fascism. Its monopoly on wireless radio meant it faced no commercial competition. Its wartime funding turned it into a nationalized industry devoted to public service. The mission objectives—to inform, educate, and entertain—were as unified as they would ever be. In short, the BBC did provide the social cement for wartime Britain, and it was a gift to the world.

None of that could last. Although neither historian here tells it that way, the story of the postwar BBC is the slow breakup of the great achievement of that period and the corporation’s gradual loss of primacy in British life. The causes were manifold. Starting in the Sixties, the ever-increasing commercial competition in television, including from a growing number of newcomers like Channel 4, led to more noisy and insistent challenges to the BBC’s funding model.

From the Eighties onward, the Thatcherite mania for privatization and the accompanying hostility to anything resembling a taxpayer-funded public service made life rocky for the BBC’s senior executives. Now seen unsympathetically as a patrician, Oxbridge-dominated elite, they had to battle a newly prevailing view that regarded the license fee as a flat tax to subsidize a bloated collectivist enterprise—which made the corporation a target for conservative culture warriors like the Tory minister Norman Tebbit, who described the BBC as in thrall to the “insufferable, smug, sanctimonious, naïve, guilt-ridden, wet, pink orthodoxy of that sunset home of third-rate minds of that third-rate decade, the Sixties.” This animus was perfectly calibrated for Daily Mail readers, but it also gave competing media empires, such as Rupert Murdoch’s, encouragement to chip away at the BBC’s supposed monopoly and maximize revenues from advertising and subscriptions—sources of income not available to the public broadcaster.

In this environment of relentless commercial competition and intermittent political hostility, the BBC could not win. Even when it made money, as it generally did through its international distribution arm BBC Worldwide (now BBC Commercial), that was held up as proof that it needed less license-fee support, could afford to be self-sufficient, and should act more like a private enterprise subject to market discipline. Finally, after years of fighting for audience share in popular television, the BBC had to face the ultimate disruption of the digital revolution.

At first, the corporation coped well: it built an excellent news site and developed a better-than-average streaming service with its iPlayer. But as overseas competitors such as Netflix, Amazon, HBO, and others came along, the iPlayer’s modest technology—and, above all, its lack of international reach (because of copyright restrictions)—left the BBC trailing commercial rivals in its ability to distribute its creative content.

If the BBC’s twenty-first-century problems were limited to managing decline in the face of adverse economic orthodoxies and technological change, that would have been enough of a challenge. But the breakup of the postwar consensus in British society—the end of any idea of a “social contract”—also created grave political challenges to Reith’s liberal project of cultural progress. The rising tensions reached a crescendo during the Brexit campaign in 2016, when the BBC could please no one—neither the Leave camp suspicious of the corporation’s liberal elite reputation, nor the Remainers for whom any attempt at impartiality on the referendum was outrageous “both-sides-ing.” No doubt, mistakes were made: the criticism of the popular political TV panel show Question Time for repeatedly inviting on as a guest the Leave provocateur Nigel Farage, despite his failure ever to win an election in his own right, seems justified. But even viewing the controversy from afar, as I was, it was impossible not to notice a nasty, misogynist edge to some of the Remainer fury at the BBC’s then political editor, Laura Kuenssberg, for trying to report on Brexit in an evenhanded way.

That approach of balance and fairness was certainly in the mainstream BBC tradition—and was, in fact, justified by the ultimate 52–48 vote in favor of Brexit. But what has become apparent is that the BBC is simply not an institution designed to cope with populist insults to its integrity. A fresh instance occurred earlier this year, when the popular soccer show presenter Gary Lineker was suspended over a tweet that was strongly critical of the government’s new hard-line immigration policy. After an outcry, which highlighted the BBC’s inconsistent and vague social media rules, Lineker’s bosses reinstated him and apologized—to the fury of the Daily Mail caucus. The affair perfectly confirmed the angry convictions of both liberals and conservatives about BBC “bias.” Auntie is, as Britons say, on a hiding to nothing.

Under severe pressure in the last two decades of its century of existence, the BBC’s deepest wounds have unfortunately been self-inflicted. Two of the most high-profile scandals have involved journalistic failures. The first was of standards: in May 2003 information on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction was alleged by a BBC reporter to have been “sexed up” by the government to suggest that Iraq could deploy biological weapons within forty-five minutes; the defense official identified as the reporter’s principal source subsequently committed suicide, and the journalist later admitted to misreporting the forty-five-minute claim. The second was of ethics: in 2020 it was revealed that the BBC’s star interviewer Martin Bashir had used deceptions such as faked bank statements to obtain his blockbuster sit-down with Princess Diana twenty-five years earlier.

But these disastrous episodes pale in comparison to the BBC’s mishandling of revelations about the sexual abuse perpetrated by one of its most beloved entertainers, Jimmy Savile. Savile had started out in the Sixties as one of the hosts of Top of the Pops, the immensely popular weekly TV chart show that featured live performances by hit-making bands. After that, from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, he hosted his own show of feel-good do-gooding, Jim’ll Fix It, which involved championing local causes submitted by viewers—specifically child viewers.

An official investigation published in 2016, five years after Savile’s death, reported that he had abused hundreds of victims—many of them minors, and most but not all female—over decades and at “virtually every one of the BBC premises at which he worked.” To cap a yearslong pattern of failing to investigate credible reports of his misconduct, the BBC had even spiked a critical report by its own flagship news program not long after Savile died. If the BBC was supposed to be a temple of truth and beauty, a secular version of the church, this was its equivalent of priest abuse.

In Human Voices, before falling into his Tempest-inspired reverie, DPP Haggard recalls “Eric Gill at work on those graven images, high up on the scaffolding, his mediaeval workman’s smock disarranged by the breeze, to the scandal of the passers-by.” Back in 1930, Fitzgerald writes, “the sculptor and the figures had both appeared shocking.” The BBC’s governors received complaints from the public about the scale and prominence of the naked Ariel’s genitals. (Reportedly, Gill was asked to make adjustments.)

What Fitzgerald could hardly have known when writing her novel is that Gill’s louche bohemianism concealed something altogether darker. A 1989 biography revealed that he had sexually abused his teenage daughters and also had incestuous relationships with his sisters; even the family dog did not go unmolested. This led to a series of reappraisals of his works and their curation, the latest being an incident in January 2022 when a man scaled the front of Broadcasting House and tried to make his own adjustments with a hammer.

The Gill affair should be a footnote in the BBC’s history—after all, no one then at the corporation could have had a clue about his behavior—but the Savile scandal gave it a contemporary resonance that apparently motivated the man with the hammer. There was a sense that the BBC had failed—not only in its mission, but in a basic duty of care.

The cynicism of Fitzgerald’s DPP seems sadly fitting: “All this was so that virtue should prevail. The old excuse.” The BBC is hardly alone in its troubles as an institution facing accusations of hypocrisy and abused privilege. Perhaps populist grievance will recede in Britain, and a new social contract will follow, so that a corporation based on paternalist public service can endure another hundred years. But the original spell is broken. The BBC has left the enchanted isle of midcentury Britain. Hard to avoid now is a queasiness about what will come next.