Visiting the photographer Sim Chi Yin’s show in Berlin was, for me, an exercise in keeping focus. My instinct was to look away. Too many of the faces displayed—whether of eighty-year-olds exiled from their homeland or rural families dressed neatly for studio portraits—resembled those of people I’ve known. In some photographs I could almost see my parents, growing up in communities on the edge of the Malaysian jungle. In an image of exhausted war prisoners, I felt I saw my own face staring into the camera in terror and resignation. All the people in the photographs—Chinese Malayan Communists photographed mainly by the British Army in the 1950s—had been either executed or deported.

Then in a corner of the exhibit’s final room I saw a fragment of a hand-drawn map, enlarged to show an intricate network of hills, dams, and rivers traced out like veins. It had at its heart the town of Gerik, in the north of the state of Perak, which runs from the west coast of Malaysia all the way to the country’s northern border with Thailand. This is where I grew up, and where my extended family still lives. Seeing these places I knew intimately from childhood, in a gallery thousands of miles from home, I found almost unbearable.

The exhibition, “One Day We’ll Understand,” forms the major part of Sim’s extensive visual art project examining the aftermath of the war between British colonial forces and Communist fighters in Malaysia, which started in 1948 and lasted twelve years. Malayan Communists, almost exclusively from the colony’s ethnic Chinese community, waged a violent guerrilla campaign in the hopes of establishing an independent socialist republic. The “Malayan Emergency” paralyzed the economy and deepened racial divisions that still exist. It was one of the first major events of the cold war in Southeast Asia.

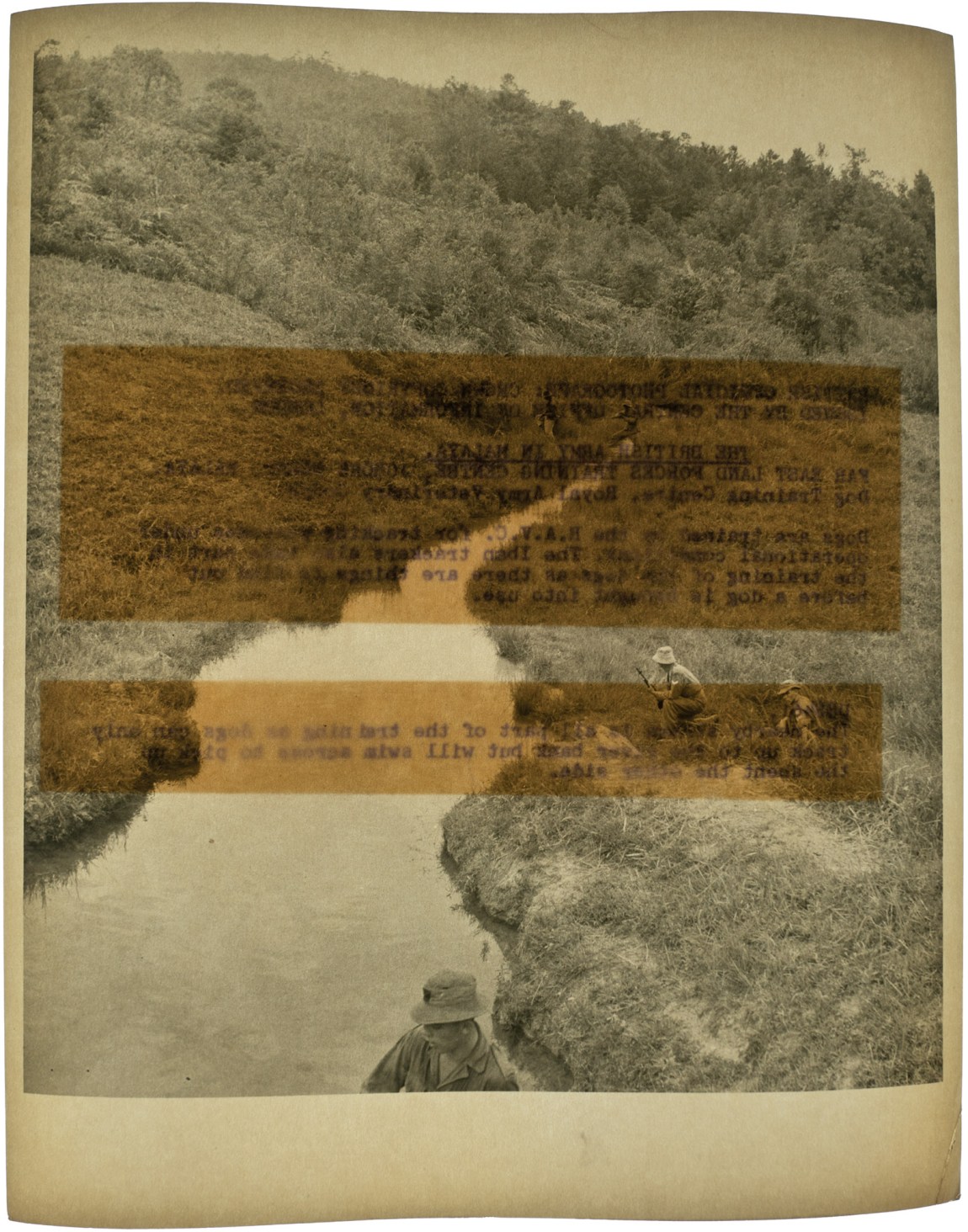

The largest group of images displayed in Sim’s show at the sprawling Zilberman Gallery in Charlottenburg was Interventions. These shots are drawn from archival material in London’s Imperial War Museum, mostly British propaganda depicting captured Communist fighters and British troops. Sim appropriated the photographs, reshooting them using a powerful backlight in order to show the serial numbers, scribbled notes, spots of glue, and typewritten captions on the reverse. A smaller collection, Remnants, is a study of objects—a uniform, a pistol, a minesweeper, the hand-drawn map—left behind by the former Malayan Communists, some of them now living in southern Thailand, close to the border. Each depicts a single item, plainly shot against a white background and hung, unframed, in a cluster on a white wall. The photo element of the show also included a few large-scale prints of the jungle landscapes that formed the backdrop to the Emergency, and Requiem, composed of video recordings of survivors of the conflict.

The final strand of the project is She Never Rode That Trishaw Again, a book that builds on the gallery show and takes it into more intimate and contemporary territory. Published to coincide with the exhibition, it is pieced together like a scrapbook, containing family snapshots and short pieces of text that attempt to make sense of how Sim’s grandmother survived the loss of her husband, a leftist intellectual who had been deported to China for being a Communist.

Born in Singapore in 1978, Sim is best known for her output as a photojournalist documenting blue-collar workers in China over the past decade. Her other work includes subjects such as Indonesian migrant workers and landscapes on the North Korea–China border for the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. In 2018 she became a member of Magnum Photos. One Day We’ll Understand draws from very personal sources. Growing up in Singapore, Sim writes, she had little knowledge of her grandparents, children of immigrants from southern China who had spent their entire lives in Malaysia. In the show’s catalog, she speaks about the distance between them, in particular the death of her grandfather, to whom she addresses this letter:

I never met you and the family—from the time I was a child—never talked about you. Except once. Dad mentioned in passing that you had died in China in the 1940s and, for some reason, had a monument built to you….

Why did the family never talk about you in the 60 years since your death? Why does grandma’s gravestone not bear your name?

Only after her grandmother died, when Sim was seventeen, did she begin to question her family’s history, piecing together a portrait of her grandfather by speaking to relatives initially hesitant to share their stories. Eventually she discovered the secret no one would talk about: that he had been jailed and deported to China by the British colonial government in Malaya as part of its extensive deportation of Malayan Communists. The resulting shame was so great that the family coped by simply shutting down all discussion of her grandfather.

Advertisement

The war began on June 16, 1948, when three European plantation managers were shot dead on their way to work near the town of Sungai Siput, about forty miles south of Gerik. The killers were young ethnic Chinese men, fighters from the pro-independence Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the armed wing of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), which sought to overthrow the British colonial regime. The following day, the British administration declared a state of emergency in Malaya, employing the euphemism at the urging of colonial tin miners and rubber planters because London insurance companies would not cover damage caused by civil wars but would do so for instances of civil disorder and riots—by contrast, the MNLA called the conflict “the Anti-British National Liberation War.”

There was good reason for alarm in Whitehall. Even before the first armed encounters, the MCP had crippled the local economy. In 1947 nearly 700,000 working days were lost to three hundred strikes organized by Communist activists. British Malaya was the world’s leading producer of tin and rubber, and the revenue generated by these commodities was crucial to Britain’s own postwar recovery: exports of Malayan rubber alone to the United States were more valuable than all of Britain’s domestic exports across the Atlantic. The protection of British economic interests swiftly led to an escalation of violence, and by the time the conflict ended in 1960, ninety British planters and an estimated five thousand civilians had died.

The relatively low death rate during this long war of attrition hides a grim practice of internment villages across the Malaysian peninsula, in which entire settlements were built and fenced off with barbed wire and subjected to strict curfews lasting up to twenty-two hours. By isolating the population in these “new villages,” the British attempted to cut off the supply of food, medicine, and information that flowed between the Communist fighters and their sympathizers, drawn almost exclusively from the rural portion of the colony’s ethnic Chinese population. Deprived of voting and land rights, these communities had a vital part in supporting MNLA fighters, many of whom came from their own families. The implementation of strict food rationing within the villages, as well as the order for military guards to shoot anyone breaking curfew, eventually did sever the material link between rural inhabitants and Communist fighters, but did little to reduce the level of leftist sympathy. At their peak, around half a million people—10 percent of the entire population of British Malaya—lived in these internment camps.

Confronting colonial propaganda is one of the aims of Sim’s project. In Interventions, her technique of shooting backlit archival material reveals annotations that seep through the surface, imbuing the images with a second layer of meaning while making the photographs themselves appear more fragile. A portrait of a group of soldiers gathered nonchalantly around a heavy artillery gun is obscured by the typed text on a piece of paper stuck to the back of the photograph. The words are difficult to read, and their blurriness invites the viewer to strain to focus on them, rather than on the men whose endeavors we are supposed to be admiring:

Ever on the alert are the British Tommies and special constables in Malaya as the battle against the Communist terrorists continues. Civilian cars are stopped and searched for arms, medicine, food etc. that might be left along the Malayan roads for the communists to pick up. The rubber industry—the staple industry of Malaya—is continually threatened by terrorist actions. Thousands and thousands of young rubber trees are every week slashed and ruined. Many by the guerillas who pin strips of paper to the trees warning estate labourers to stop working—or take the consequences.

This study of the marginalia behind depictions of British military operations lays bare the places where propaganda is unable to convince us of its reasoning—where in some cases it’s so weak that it encourages the very opposite response.

In one image of Malayan fighters in Interventions, four young men sit on the floor with their backs against the wall. Their hands are bound and they appear to be waiting, though we don’t know what for. They have been detained and may be facing deportation or execution. They do not look at the photographer, their gaze held by something further afield; their faces are tense, hardened. A single word in elegant cursive is clearly visible on the back of the photo: “bandits.” In one sense the term is not inaccurate (they are, after all, wearing the uniform of MNLA soldiers engaged in guerrilla warfare), but it is difficult to think of them only as that—difficult for me, especially, with my links to those people and that particular region, not to imagine the kind of families and homes they come from. A serial number scrawled in blue indicates the photo was approved for release to the press, a trophy of sorts.

Advertisement

Malaysia and Singapore make up the former territories of British Malaya. But even there, the Emergency is rarely discussed in detail. It is not exactly a taboo subject: I remember it being part of the history curriculum at school, but it was dealt with in a perfunctory manner, as if it had occurred in the distant past in a country other than our own. There were no widespread public reflections on the anniversary of the conflict, either its beginning or end, no national commemoration of its victims. Still today there are not. We are afraid of the conversations that will arise from addressing our historical trauma, and what they might mean for today’s fragile peace.

This reticence can be largely explained by Malaysia’s continuing racial divisions—the greater political and social advantages that the ethnic Malay majority generally enjoy over the ethnic Chinese and Indian minorities, who first arrived in large numbers in the mid-nineteenth century as indentured laborers working in tin mines and on rubber plantations. Despite the ascent of many ethnic Chinese into middle-class life, they are still excluded from the most important political posts and certain categories of land ownership under a system of race-based quotas that control entry into the civil service, enrollment in public universities, and access to government scholarships—all grievances that underpinned the Communist movement in postwar Malaysia.

Almost forgotten in this collective avoidance is the mass deportation not just of MNLA fighters but of those suspected of being Communist sympathizers. Sim’s grandfather was arrested early in the conflict and deported to China along with 30,000 other ethnic Chinese Malayans. Once there, he was executed by China’s ruling Kuomintang government. These scant details of his death are all that Sim is left with, all that we are left with.

The difficulty that Sim encountered speaks to a sense of unease within ethnic Chinese communities in Southeast Asia over their former links to Communist movements seen as treasonous. It also betrays an instinct for self-protection and a desire to integrate within societies and countries whose national identities are young and easily threatened by the idea of the dangerous, ungrateful immigrant. Or maybe that is what we have been taught to believe. Reading Sim’s interviews with family members, I recognized instantly how hard she must have pushed to obtain the stories she did. Describing a train journey with her uncle, she writes:

We were on our way back from the extended family’s first ever visit to our ancestral village in Guangdong, China, and to grandad’s grave, in 2011…. I had perhaps simplistically asked, “Why did grandma never remarry?” He wordlessly cried for what felt like a very long time. He might have been thinking of how she lived out her life alone, after having lost her husband in her mid-30s. That, for me, was a hint of the depth of the trauma that has silently sat within this family all these decades, and of the pain and loss my grandmother lived with.

I’ve been in that position myself, chronicler of family history. My own family could well have been communist sympathizers—they were poor, lived on the edge of the jungle, and were educated in vernacular rural schools—yet my weak attempts to speak to my parents about their lives during the Emergency have been met with a dismissive shrug. They do not wish this story, with its connotations of treachery and subversiveness, to be part of my identity. What Southeast Asian of Chinese descent, with parents born during or just after the war, hasn’t known this feeling of being shut out from their own history?

For a long time I saw this exclusion as a legacy of our shame: Sim’s relatives knew that their association with communism would mark them as dangerous elements in a newly independent nation. Refusing to acknowledge her grandfather’s existence was her family’s way of ensuring not just their own safety but that of future generations. Her grandmother was especially blunt in her denials. Discussing her grandmother with her uncle in She Never Rode That Trishaw Again, Sim quotes him:

It was the Cold War then. If someone mentioned that our father fought and died for the Chinese Communist Party, that was not good for us, the next generation. And we didn’t want people to know that he had been executed by the Nationalists in China…. But I once heard her dealing with inquisitive acquaintances who asked, “Eh, what happened to him?” She rebutted by saying: “He found another woman in China and doesn’t want us anymore.” In fact, she fell ill on getting that letter from China telling her that her husband was dead.

We can forgive marital infidelity easily enough, but nationality and belonging are much more difficult to process.

She Never Rode That Trishaw Again connects the historical and personal strands of Sim’s multigenerational project, illustrating the effects on her family of the wartime materials displayed on the Zilberman’s walls. The book consists of a series of holiday snapshots interspersed with short excerpts from interviews with Sim’s uncle. Some of the pages act as pockets containing reproductions of postcards from various locations—Tokyo, Karachi, London, Geneva—sent by various family members. Most of the images are of Sim’s grandmother. We see a woman aging gracefully with the Golden Gate or the Sydney Opera House in the background—standard holiday snaps from the 1970s and 1980s.

Twenty-five years after Sim’s grandfather was deported and executed, her grandmother was traveling the world. In one generation, the family had transformed itself from rural shopkeepers on the edge of the Perak jungle to middle-class holidaymakers in foreign lands. Achieving this required something more radical than working hard to earn money; it demanded a resolute silence about her recent past. I realize now that our families’ denial is based not on the desire to exclude future generations from their history, but on the instinct to protect them from it. That way, when we look back, all we have are these snapshots of ease and happiness.

But this kind of denial is dangerous. In a short film that plays on two television screens, Sim provides her final reminder that we have not completely uncoupled ourselves from our past. Now-elderly deportees sing the “Internationale” and “Goodbye Malaya,” one a hymn of idealism, the other of loss. Exiled to the remote jungles of Southern Thailand and unable to return to Malaysia, they are now in their eighties and nineties.

I saw an earlier iteration of Sim’s show at the Montmajour Abbey in Arles, where it was mounted for a photography festival, Les Recontres de la Photographie d’Arles. There, the screens were hidden behind a wall of large-scale photographs—an elephant emerging from the forest at night, a table and chairs in an isolated rural shack. The fragile voices, singing in Mandarin about having to leave one’s country, drifted across the twelfth-century cloister, and when I finally found where they were coming from I wished I hadn’t. The men and women in the film looked so much like my grandparents that I was forced, again, to remember that my sense of belonging to a national project was built on their exclusion from it.